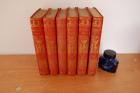

sold with 6 volumes of the History of the War in the Peninsula and in the South of France from the Year 1807 to the Year 1814. 6 vols (complete) by Napier, W. F. P. (Major-General Sir William Francis Patrick)

Published by Frederick Warne and Co., London, 1890 " The Chandos Classics" All six volumes in this "Chandos Classics" edition are clean and sound, with slight sunning to spines, lightly bumped spine ends. A definitive study of Napoleon's War in the Iberian Peninsula and the southern parts of France. Part of the Chandos Classics series, there is no date stated, but this edition is believed to have been printed in 1890

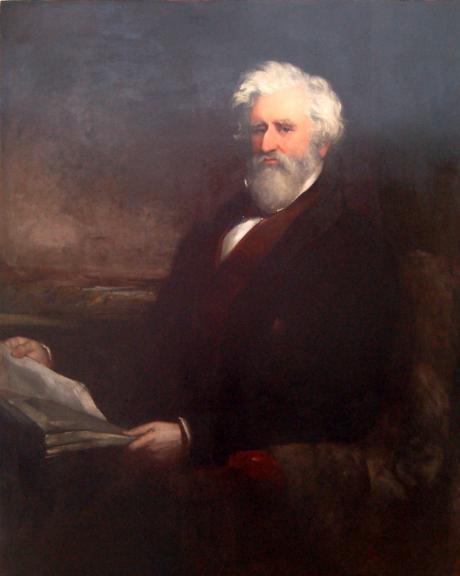

Elizabeth Marianne Napier, 2nd daughter of the Sitter,who married the 4th Earl of Arran and thence by descent to the Earl and Countess of Arran, Castle Hill, Devon

Napier, Sir William Francis Patrick (1785–1860), army officer and writer, born at Celbridge, co. Kildare, on 17 December 1785 was third son of Colonel the Hon. George Napier (1751–1804) and his second wife, Sarah (1745–1826), née Lennox, formerly married to Sir Thomas Bunbury. He had four brothers—General Charles James Napier (1782–1853), Lieutenant-General George Thomas Napier (1784–1855), Captain Henry Edward Napier RN (1789–1853), and Richard, QC—as well as a half-sister, Louisa (d. 1854), from his father's first marriage, and three sisters (Emily, Cecilia, and Caroline). The Napiers claimed descent from Scott of Thirlestane and John Napier, the inventor of logarithms; William's mother, daughter of the second duke of Richmond, from Charles II.

Napier spent his youth at Celbridge House, according to his sister Emily attending ‘the village school’ but spending ‘much of his time with a vagabond called Scully … [who was] something of a poacher’ (Bruce, 1.7). From an early age Napier showed pugnacious self-reliance, once effectively wielding a large bag of marbles against a troublesome bully, and, during the 1798 Irish rising, the five Napier boys were armed to defend the family home. William Napier was commissioned second-lieutenant in the Royal Irish Artillery on 14 June 1800, became a lieutenant in the 62nd foot on 18 April 1801, and went on half pay after the peace of Amiens in March 1802. Through its colonel and his uncle, the duke of Richmond, on 22 August 1803 Napier acquired a cornetcy in the Horse Guards, moving as lieutenant on 28 December 1803 to the 52nd light infantry, part of Major-General John Moore's light brigade at Shorncliffe. Impressed by Napier, Moore thereafter took a close interest in his career. Napier nominally secured a company in a West India regiment on 2 June 1804, and shortly afterwards a battalion of reserve. On 11 August he became a captain in the 43rd light infantry at Shorncliffe, when the 43rd had a poor professional reputation. In the words of a fellow officer, showing an aptitude for ‘leaping, running, swimming &c’ and displaying ‘naturally polished, pleasing, gay manners’ (ibid., 1.24), Napier soon transformed his company.

Two months after Napier's father died, in December 1804 Captain Charles Stanhope of the 52nd introduced him to his uncle, William Pitt, though the association had no political effect on Napier. In 1806 Napier went to Ireland to recruit militia volunteers for line regiments. The following year, he and the 43rd sailed with the British expedition to Denmark and fought at Kjöge, before the 43rd returned to Maldon and then Colchester. The 43rd embarked for Corunna on 13 September 1808, on arrival marching inland to Villafranca, where it formed part of the rear-guard covering Moore's retreat to Corunna; Napier spent two days and nights under attack at the Esla River, while his men demolished the Castro Gonzalo bridge. Rejoining the main force, he led a convoy of sick and wounded over the mountains to Vigo, marching for several days with bare feet, clad only in a jacket and pair of trousers. Not surprisingly, he suffered debilitating fever. Back home, in February 1809 he became aide-de-camp to the duke of Richmond, lord lieutenant of Ireland, but four months later went back to his regiment in Portugal. En route for Talavera, he was left at Placencia, suffering from pleurisy. When only partially recovered, he reputedly walked 48 miles to Oropesa and took post-horses for Talavera, where he promptly collapsed.

Fit again, Napier saw action on the Coa, 23 July 1810, and was shot in the left thigh as his company covered the light division's withdrawal. Still in discomfort, he fought at Busaco on 17 September 1810, as Wellington retired towards the lines of Torres Vedras. When the French retreated into Spain the following year, Napier saw action at Pombal, Redinha, and Casal Novo where, on 14 March 1811, a musket ball (never removed) lodged near his spine: paralysed below the waist, ‘I escaped death by dragging myself by my hands … towards a small heap of stones which was in the midst of the field, and thus covering my head and shoulders’ (Bruce, 1.55). His wound had not fully healed when Napier acted as brigade major at Fuentes d'Oñoro on 5 May 1811. He received a brevet majority on 30 May, but fell ill in June; he was sent to Lisbon, and in the autumn to England. In February 1812 Napier married Caroline Amelia (1790–1860), younger daughter of General the Hon. Henry Fox and niece of the politician Charles James Fox. Learning that Wellington was besieging Badajoz, three weeks after his wedding Napier once more set off for active service. Arriving after the fortress had fallen he found that Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Macleod had been killed, and took command of the 43rd as the senior officer present. On 14 May 1812 Napier advanced to regimental major and led the regiment at the battle of Salamanca on 23 July in a steady 3 mile advance under heavy fire to seize the ford at Huerta, and entered Madrid with Wellington on 12 August. When the 43rd subsequently withdraw into Portugal, he went to England on leave from January to August 1813, rejoining the regiment at Vera, in the Pyrenees. On 21 September, disturbingly he informed his wife that his wound was painful and ‘the doctor’ thought ‘a small part of the ball or backbone [was] coming away’ (ibid., 1.150).

When its commanding officer became unwell, during the battle of the Nivelle, Napier took over the 43rd again, and at its head, on 10 November 1813, stormed a strong, entrenched enemy position on a steep, rocky hill, Le Petit Rhune. After Wellington forced the Nive River, the French commander Soult suddenly attacked the light division on the left bank on 10 December. For three days Napier successfully defended the church at Arcangues, being wounded in the right hip and, less seriously, when a shell splinter drove his telescope into his face. Promoted brevet lieutenant-colonel on 22 November 1813, he fought at Orthez on 27 February 1814, but, laid low with fever and dysentery, he returned to England on sick leave in late spring. He briefly attended the senior department of the Royal Military Academy, Farnham (25 February – 10 June 1815), before hastening to his regiment on news of Napoleon's escape from Elba. He missed the battle of Waterloo, but marched with the 43rd to Paris and took part in the victory parade. Napier served with the 43rd in the army of occupation until late 1818, when the 43rd moved to Belfast, where he had the opportunity to purchase its command. For financial reasons he declined, and on 17 June 1819 went on half pay. From the officers of the 43rd he received a sword ‘as a testimony of their sincere regard for him and their high admiration of the gallantry and conduct he ever displayed during his exemplary career’ (Bruce, 1.217). He was made CB on 4 June 1815, and received a gold medal with two clasps for the battles of Salamanca, the Nivelle, and Nive, and a silver medal with three clasps for Busaco, Fuentes d'Oñoro, and Orthez..

In retirement, at a rented house in Sloane Terrace, London, Napier pursued ‘rather a desultory though never an idle life, without any absorbing aim’ (Bruce, 1.224) until he reviewed Baron Jomini's Principes de la guerre for the Edinburgh Review in 1821, and, afterwards, met Marshal Soult in Paris. Encouraged by Henry Bickersteth (later Lord Langdale), despite lack of literary experience, Napier determined to write a history of the Peninsular War. Wellington refused use of his private papers, but gave Napier Joseph Bonaparte's correspondence with Napoleon, senior military figures, and politicians captured at Vitoria, and answered copious questions. For some months in 1824 Napier lived in a cottage at Stratfield Saye, but the duchess banned him from the house, because of his ‘commonplace opinions in politics’ (Longford, 113). Sir George Murray, quartermaster-general in the Peninsula, denied him access to documents and maps in his possession, though Soult proved more accommodating when Napier returned to Paris, where he met other Napoleonic commanders, Ney's widow, and Jomini. Wearied through copying copious documents, he complained to his wife that ‘my health is bad, my spirits worse, and my expenses very great’, longing for the time when ‘we will paint and walk, and read and write history’ (Bruce, 1.243, 244). Indeed, Caroline (Caro to Napier) was closely involved in Napier's work, especially in deciphering the codes in Joseph Bonaparte's correspondence. Back in England Napier used journals and other printed sources, and corresponded at length with many British and French officers. For many years blind and frail, Napier's mother died on 20 August 1826. Shortly afterwards the family moved to Battle House, Bromham, near Devizes, where Napier read the works of William Cobbett, copied his system of cultivating Indian corn, and, as his daughters observed, frequently dug the kitchen garden ‘wearing a labourer's white smock frock’ (ibid., 1.297). He developed, too, a lasting friendship with the poet Thomas Moore, who lived close by.

Relying on a major's half pay of 9s. 6d. a day, Napier worried incessantly about money. He wrote to Lord FitzRoy Somerset (later Lord Raglan), military secretary at the Horse Guards, on 30 November 1826 seeking emolument for his third wound suffered at Arcangues, which he had not listed for fear of alarming his pregnant wife. John Murray paid Napier 1000 guineas for the copyright of the first volume of his history, published in 1828, and secured an option on the next three volumes, which he did not exercise due to financial loss on the first. So Napier raised subscriptions from individuals for Thomas and William Boone to bring out the last five volumes. The history provoked wide-ranging reaction. Soult considered it ‘perfect’, Sir Robert Peel ‘eloquent and faithful’, the Spanish general Alava felt it too pro-French, and a British officer in India demanded satisfaction on his return for a ‘most unfounded calumny’ about his conduct at Barossa. General Lord Beresford expressed fury at the account of Albuera, and, fourteen years after publication of the relevant volume, Colonel John Gurwood would challenge Napier's assertion that a howitzer captured at Sabugal fell to the 43rd, not 52nd, regiment. Napier thus faced a carillon of malcontents and critics, and he believed that his adverse comments about the Spaniards prevented him from commanding British troops in the Carlist wars. The work was, however, translated into French, Spanish, Italian, and German, with plans to produce a Persian version also discussed.

Napier advanced to colonel on 22 July 1830, and towards the close of 1831 moved the family to Freshford, near Bath, where he became politically outspoken, pronouncing the Reform Act too mild, the corn laws defensible (opposing their repeal), and the Poor Law Amendment Act unacceptable; in 1841 he published Essay on the Poor Laws and Observations on the Corn Laws. He spoke in favour of universal suffrage, the secret ballot, and annual parliaments without joining the Chartists, and he espoused the anti-slavery cause. However, he vigorously defended flogging in the army and opposed the abolition of purchase. A long-standing friend, James Shaw (later General Sir James Shaw Kennedy), believed him in 1805 to be ‘nothing more than a complete whig of the school of Charles Fox’ (Bruce, 1.346), but thirty years later he had drifted from the whigs and become a confidant of the radical MP J. A. Roebuck. In 1831 enthusiasts vainly urged Napier to head a national guard and, in 1848, to lead a march on London to demand reform. Napier declined invitations to stand for parliament in Bath, Nottingham, Glasgow, Devizes, Westminster, Oldham, and Kendal, citing inability to meet the costs involved and maintain his large family, to which he was devoted. He and his wife had one boy and nine girls (John Moore and Henrietta both being born deaf and mute); four of the girls predeceased their parents. ‘How I do love my girls’ (ibid., 1.196), he declared, and he worried particularly about the security of his son's clerical post in the quartermaster-general's office in Dublin. In 1833 his eldest surviving daughter, Fanny, died of consumption. Napier spent hours alone with his brother Charles during his last illness in September 1853, but, a month later, his brother Henry died before he could reach his sickbed. His half-sister, Louisa, passed away in 1854; a year later his brother George died in Geneva. These two depressing years had been prefaced by the death in September 1852 of Wellington, whom Napier so fervently admired and to whom he had dedicated his history. Grief-stricken, he carried a bannerol at the funeral on 18 November, and watched, with a select few, as the duke's coffin was lowered into its vault at St Paul's Cathedral.

Worries about finance were ever present. In 1833 Napier fleetingly considered leaving the army: his annual salary amounted to a mere £171 and, should he die, the value of his commission would be lost to the family, whereas it could be sold for £3200. Four years later he applied for ‘additional pay for meritorious services’, and secured £150 a year. In 1846 Napier was delighted when Lieutenant-General James Shortall, his commanding officer in the Royal Irish Artillery, bequeathed him £100. Nevertheless, money rarely motivated his extensive writing, as he sought to redress perceived injustice, promote national security, and debate historical issues in numerous publications and private correspondence. Occasionally he adopted the nom de plume Elian. He attacked Louis Thiers, the French statesman, for dismissive comments on Wellington and Moore. Thiers retorted that he would not waste time in refuting ‘the assertions of ignorant or interested critics’, and Napier acidly returned that he should write ‘in a manner to avoid the just censures of honest and well-informed critics’ (ibid., 1.555). When his brother Charles was attacked for his conduct as a military commander and civilian administrator, Napier leapt to his defence in a two-volume History of the Conquest of Scinde. It attracted fierce criticism, and his son-in-law admitted that, in this work, ‘the calmness of the historian is too often wanting’ (ibid., 2.193). After Charles's death, Napier completed his brother's Defects, Civil and Military, of the Indian Government. He then wrote a biography of Charles, which ignited yet more acrimonious public exchanges.

Napier displayed a keen interest in imperial and foreign affairs. During disturbances in Canada in 1838 he argued that ‘Lower Canadians have been infamously used, and were driven into armed rebellion’ (Bruce, 1.473). As cross-border relations with the United States deteriorated, he devised a plan for attacking over the Niagara River. With France on the verge of anarchy in 1848, he saw Louis Napoleon as its saviour: ‘Vive Napoleon … Will he be Napoleon the Third, or Dictator, or Consul, or President?’ (ibid., 2.255). As Britain became embroiled in the Crimean War, he stoutly defended his cousin, Vice-Admiral Sir Charles Napier, who was vilified for an ineffective foray into the Baltic, mused as to whether Sevastopol would ever fall to the allies, condemned the use of ‘hirelings of Germany and Switzerland’ (ibid., 2.363) in a British foreign legion, felt that issue of the Minié rifle to all infantry would stifle attack on the battlefield, and minutely analysed reports of the major land actions. He retained, too, his fascination for the Napoleonic era. When Soult visited Britain in 1838, he accompanied him to Manchester, Liverpool, and Birmingham, and they spoke at length about political and military figures of the First Empire. In February 1842 Napier was appointed lieutenant-governor of Guernsey, where he condemned the ‘wretched state’ of the island's defences, the dismal condition of the militia, and harsh, biased application of the law by the judiciary. When he left office in January 1848 he had achieved little in the face of entrenched, powerful families and a hostile press, except the appointment of one royal commission to examine the administration of criminal law, the promise of a second to look into civil law, and the recommendation from a military commission to strengthen coastal defences of Guernsey and Alderney.

Napier's chief publications were: History of the war in the Peninsula and in the south of France from the year 1807 to the year 1814 (6 vols., 1828–40), Reply to Various Opponents, together with Observations Illustrating Sir John Moore's Campaign (3 vols., 1832–3), The conquest of Scinde, with some introductory passages in the life of Major-General Sir Charles James Napier (2 vols., 1845), History of Sir Charles Napier's Administration of Scinde and Campaign in the Cutchee Hills (1851), English Battles and Sieges in the Peninsula (1852), and The Life and Opinions of General Sir C. J. Napier (4 vols., 1857). He also wrote innumerable reviews, articles, pamphlets, and letters to the press, many of them contentious and polemical, and he contributed ‘An explanation of the battle of Meanee’ to the Professional Papers of the Royal Engineers (1844).

Promoted major-general on 3 November 1841, Napier was appointed colonel of the 27th foot on 5 February 1848 and created KCB on 29 April. The following year he and his family moved to Scinde House, Clapham Park, where he stayed for the rest of his life. He advanced to lieutenant-general on 11 November 1851, and succeeded Charles as colonel of the 22nd foot on 19 September 1853. However, his health noticeably declined during the winter 1857–8, and, in October 1858, he narrowly survived a severe paroxysm. In March 1859 he wrote of ‘being on my death-bed’ and, from April, dictated letters to his daughter Caroline. None the less, his mind remained alert. He reflected extensively on the defences of the British Isles and the military capability of European countries. His last paper, dictated in December 1859, contained comprehensive guidance to Bruce on raising a force of volunteers. Napier was promoted general on 17 October 1859, but by then his wife had developed severe dropsy, which deeply depressed him. During the morning of Sunday 12 February 1860, she was briefly wheeled into her unconscious husband's room. At 4 p.m., in the presence of his children, grandchildren, sons-in-law, and daughter-in-law, Napier passed away ‘so gently that it was impossible to say when the breathing ceased’ (Bruce, 2.483). The funeral at Norwood was private, although light division veterans from the Peninsula attended. Napier's wife survived him by six weeks; of his brothers, only Richard outlived him.

Appearance, character, and conclusion

Napier stood 6 feet tall, with black curly hair, fierce moustachios, short-sighted blue-grey eyes, an aquiline nose, firm mouth, and square jaw. In later years, he had flowing white hair and a full beard. According to his son-in-law, he could be ‘so terrible in anger, so melting in tenderness, so sparkling in fun’ (Bruce, 1.27). Napier reacted swiftly and often savagely when he believed himself, his family, or friends unfairly treated. He admitted undertaking his work on the Peninsular War principally because he considered Robert Southey's account unfair on Moore and the French army. A century afterwards, in his History of the British Army, J. M. Fortescue questioned the reliability of Napier's information and figures from unidentified sources, and C. W. C. Oman justifiably deemed the history ‘magnificent (if somewhat prejudiced and biased)’ (Oman, Wellington's Army, 18). Military historians now treat it with considerable caution.

If Napier was not the ‘genius’ which Bruce and Shaw Kennedy claimed, he had many creative attributes. Lacking detached and balanced judgement, he was nevertheless a prodigious writer of history, biography, and social and political treatises. He painted, mainly for recreation, though George Jones RA, held that his ‘talent in drawing was very considerable, and if he had studied for the profession of painting I believe he would have been very successful’ (Bruce, 2.490). Napier wrote poetry (notably the seven-verse ‘Ode to Love’) and sculpted competently; for his statuette of Alcibiades he became an honorary member of the Royal Academy. He was also elected to the Athenaeum and the Swedish Academy of Military Sciences. A statue of Napier by G. G. Adams, inscribed ‘Historian of the Peninsular War’, was installed in St Paul's Cathedral.

John Sweetman DNB

Watts, George Frederic (1817–1904), painter and sculptor, was born on 23 February 1817 at 52 Queen Street, Bryanston Square, Marylebone, Middlesex, the eldest child of the second marriage of George Watts (1775–1845), pianoforte maker and tuner, and his wife, Harriet Ann (1786/7–1826), daughter of Frederic Smith.

Watts became, by the last two decades of his long life, one of the most famous painters in the world. The progress of this extended career resulted in an enormous output of some 800 paintings, as well as countless drawings and some sculpture. At the time of his death in 1904 he held a clutch of honours, most notably the newly instituted Order of Merit. He is still widely recognized as one of the greatest English portrait painters, but his critical fortunes have fluctuated widely since his death, and many of his major ‘symbolical’ subject paintings still provoke questions.

Family history and early life

Watts's grandfather, also George (b. 1746), a cabinet-maker, left Hereford, the family's home, to settle in London in the mid-1790s. His eldest son, Watts's father, was first married in St Mary-le-Bone Church in 1799 to Mary Ann Williams, who died in 1813 after four children were born. Among the three children who survived to adulthood were Watts's half-brother, Thomas (b. 1799), who carried on the family pianoforte business and had his own large family, and two half-sisters, Maria (1801–1884) and Harriet (1803–1893). These two women took charge of their father's home after the death of his second wife, whom he had married in 1816. Watts repaid this attention by accepting responsibility for them once he had some success, continuing to do so until their deaths, even though his own wife did her best to expunge references to Watts's family in her memoirs of the artist.

Despite social aspirations, Watts's father struggled to maintain his family in difficult circumstances. His sickly infant was baptized privately at home. The name George Frederic seems to have been an allusion to his father's musical interests by invoking Handel, the anniversary of whose birth fell on the same day as that of the new baby. Life in the strict sabbatarian and evangelical household had its constraints, with a severe routine on Sundays, later recalled by the artist, and this narrow religious routine seems to have prompted his own turn away from organized religion. Family deaths dominated Watts's early life, as the three brothers born after him died, two in a measles epidemic in 1823 when Watts, aged six, was old enough to feel the impact of this double tragedy. Still worse was the death of his mother, probably from consumption, in 1826 when he was only nine, an event that made the reality of death painfully immediate. Declining family fortunes led to a move to Star Street, Paddington, Middlesex. Poor health prevented Watts from attending school regularly, but his talent for drawing emerged in numerous sketches and copies, and in these efforts his father encouraged him. Many early drawings are still preserved in his earliest sketchbook (priv. coll.). A keen reader, Watts knew the Bible, the Iliad, and the works of Sir Walter Scott from an early age and their content inspired his first drawings.

In 1827 Watts entered the studio of the sculptor William Behnes, a family friend of Hanoverian descent whose father was also a pianoforte maker. In the busy open studio on Dean Street, in Soho, London, Watts worked on an informal basis, learning in the accepted academic method of copying: studies in physiognomy (1828, after Fright, one of Charles Le Brun's têtes d'expression); engravings after the old masters (1828, heads after Raphael); and modern artists, such as Richard Westall (1830, Archangel Uriel and Satan) and John Hamilton Mortimer. Watts's father brought some drawings to the attention of the president of the Royal Academy, Sir Martin Archer Shee, who pronounced: ‘I can see no reason why your son should take up the profession of art’ (Watts, Annals, 1.22). This comment did not deter the young artist in his independent studies, but it may well have encouraged his lifelong scepticism about the powers of the Royal Academy. Behnes provided Watts with access to plaster casts of the Elgin marbles and these led him to seek out the originals, newly installed in the British Museum in 1832. Watts's own assessment of his early training focused exclusively on the impact of these works: ‘The Elgin Marbles were my teachers. It was from them alone that I learned’ (Watts MSS, Strachey 1895). Benjamin Robert Haydon, the great propagandist for these masterpieces, visited Behnes's studio in the mid-1830s and, according to Emilie Barrington, encouraged Watts to continue studying the marbles, inviting the young artist to visit his own studio.

Behnes's example as an accomplished draughtsman turned sculptor presaged Watts's own willingness to work in different media. He admired Behnes's portrait drawings, soon developing a facility for such works himself, enabling him to earn his own money from 1833, with portraits in coloured chalks and pencils. Based by this time in the new studio at Osnaburgh Street, Watts befriended Behnes's younger brother, Charles, a miniature painter whose steady temperament offset that of his wilder, more successful brother. Charles introduced Watts to wider literary horizons and on a practical level arranged for a friend to provide some tuition in oils. The success of his copies, including one after Van Dyck (formerly Watts Gallery) smoked to appear old, started Watts towards more formal training as a painter.

Early career

Watts entered the Royal Academy Schools on 30 April 1835 and, as was the norm, he studied first in the antique school. In 1863 he evaluated the experience, stating that he entered the schools ‘when very young, I do not remember the year, but finding that there was no teaching, I very soon ceased to attend’ (RA Commission). His handling of oils had already advanced to a degree of fluency, as exemplified by the Self-Portrait of about 1834 and a portrait of his father (1836; both Watts Gallery, Compton, Surrey), both sensitive character studies. By this time, aged eighteen, he already earned his own way, in small-scale portraiture, a further disincentive to pursuing his studies in the schools. Even so, Watts matured as an artist in the 1830s when the ideal of history painting was still very much alive and he inherited a belief in ‘high art’. At this time William Hilton was the leading representative of history painting in the academy and some of Watts's early paintings show this influence, as, for example, Ruth and Boaz (c.1835–6; Tate collection). As keeper of the Royal Academy during Watts's time there, Hilton praised the young man's drawings but discouraged him from painting ‘anything original in the way of composition’ (Watts, Annals, 1.26–7) when the young artist already felt able to do so. Recorded on the schools' books for two years, Watts attended only intermittently; he first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1837 with The Wounded Heron (Watts Gallery, Compton, Surrey) and two portraits, from 33 Upper Norton Street, Marylebone. By 1838 he had taken his own studio at nearby Clipstone Street where, according to family tradition, the Watts pianoforte business traded.

During the 1830s Watts's leisure pursuits included studying languages, choral singing, and cricket. These interests combined in his friendship with Nicholas Wanostrocht the younger (1804–1876), of the Alfred House school in Blackheath, who became better known as the cricket authority Nicholas Felix, author of Felix on the Bat (1845). For Felix, Watts drew a series of accomplished drawings of cricket positions (he presented five of the seven to the Marylebone Cricket Club in 1895; now in the museum at Lord's cricket ground) that served as the basis for a set of lithographs published in 1837.

Patronage provided the key for Watts's continuing success as a portraitist of small, neat oils. Commissions from London's middle classes along with the occasional aristocratic portrait, such as The Children of the Earl of Gainsborough (c.1840–42), helped the young painter establish his practice. He painted John Roebuck MP (engraved 1840) which led to a curious commission to paint a portrait of Jeremy Bentham (ex Christies, 14 July 1994) from a wax effigy (now at University College, London). The most important source of work came from the family of émigré Greek shipping merchant Constantine Ionides (1775–1852) whose business was located in the City of London. In 1837 Watts received a commission from his son Alexander Constantine Ionides (1810–1890) to copy Samuel Lane's portrait of Constantine (exh. RA, 1837) for the sum of £10. The family preferred Watts's copy, which they kept, to the original, which they sent back to Greece. Watts also painted the young family of Alexander Constantine Ionides, who was close in age to the artist and an eventual friend, in a vivid portrait (now destroyed; oil study, V&A) of the transplanted Greeks in their traditional dress. Watts's association with the Ionides family carried on through several generations and indirectly fuelled his own appreciation of ancient Greek sculpture.

Although Watts's portrait practice flourished, the ideals of high art impelled him to succeed as a history painter. His earliest efforts at subject painting derived from romantic literature; he soon tackled the traditional subjects for history painting, from classical literature and history, as in The Fount (c.1839; exh. British Institution, 1840) from the Iliad. His history paintings became increasingly ambitious, as Cincinnatus (c.1840; priv. coll.) suggests; the subject had a clear stoical message and obvious moral, thus looking back to neo-classical history paintings. In this work, for the first time, Watts's style with massively conceived, over life-sized figures reflected the inspiration of the Elgin marbles.

In April 1842 the Fine Arts Commission announced an important competition to promote large-scale historical painting to decorate Charles Barry and A. W. N. Pugin's new Palace of Westminster. Artists submitted cartoons (large drawings) with life-sized figures, illustrating scenes from British history or from the native poets, Shakespeare, Milton, and Spenser. By now with his own larger studio in Robert Street off Hampstead Road, Watts prepared an entry to fit the requirements, selecting a work he already had in hand, Caractacus Led in Triumph through the Streets of Rome (original in three fragments, V&A), from Tacitus's Annals of Imperial Rome (12.31–5). The exhibition of 140 entries opened in June 1843 in Westminster Hall. Watts's work impressed the judges, who included Samuel Rogers, Henry Petty-FitzMaurice, third marquess of Lansdowne, Sir Robert Peel, and three Royal Academicians. Caractacus bore the hallmarks of good draughtsmanship and a textbook composition based on the example of Raphael, with many figures amassed into clearly readable groups. Watts, along with Edward Armitage and Charles West Cope, won the highest premium of £300, enabling him to travel abroad to study the techniques of fresco painting in Italy. His poverty had prevented him from making an artistic ‘grand tour’ earlier but clearly he saw it as a way to improve his prospects, and embarked early in July 1843.

Travel and life in Italy, 1843–1847

After crossing the channel Watts initially spent six weeks in Paris, staying with his friend and fellow premium winner, Armitage, who trained in the studio of Paul Delaroche. At the Louvre, Watts studied the old masters but there is little evidence of his other activities. In early September he travelled by diligence from Paris to Chalon-sur-Saône, an uncomfortable journey of several days. He carried on by river steamboat via the Saône and Rhône to Avignon and thence to Marseilles. En route for the next port of call, Leghorn, Watts met English travellers, General Robert and Mrs Ellice, friends of the British minister at the court of Tuscany, Henry Fox, fourth Lord Holland. They suggested Watts seek out Lord Holland in Florence. He meanwhile travelled onward in an open country cart during the Tuscan vintage season, stopping in Pisa for a few days, then going on to Florence, where he planned to stay for a month or two.

In Florence Watts initially studied art and culture, but on prompting from General Ellice he finally made several visits to Lord Holland's house, Casa Feroni, a vast eighteenth-century villa on the via dei Serragli. He accepted the offer to stay there for a few days until he found suitable lodgings to extend his stay in Florence, eventually staying for several years.

The Fox/Holland papers document Watts's life at the heart of a cosmopolitan circle of rich aristocrats and expatriates (Holland House MSS). In the Casa Feroni and the Villa Careggi, the former Medici villa in the hills outside Florence, to which the Hollands retreated, the young artist enjoyed many comforts, befriending Lord Holland's childless wife, Lady Augusta, in particular. Her informal portrait in a ‘Riviera’ (or ‘Nice’) straw hat (1843; Royal Collection) documents the spirit of their new friendship with a lighter palette reflecting the artist's newly lightened mood. Watts made many personal friends from among the Holland circle and, by way of thanks to his hosts, he made a series of sensitive portrait drawings in the manner of Ingres, indicating his assimilation of a continental mode in his own work. He also executed lively caricatures and more seriously conceived oil portraits, such as Lady Augusta Fitzpatrick (Tate collection), a full-length, grand-manner portrait. Social occasions provided opportunities, such as the costume ball in February 1845 when Watts donned a discarded suit of armour for a Self-Portrait (priv. coll.). He displayed his new self-image as a young man imbued with the Italian Renaissance past, reinventing himself as a romantic, far from London. Italian literature and history inspired the series of grand subject paintings that the artist executed in his spacious garden studio at Careggi, including The Origin of the Quarrel between the Guelph and Ghibelline Families (Watts Gallery, Compton, Surrey).

Watts expanded his artistic repertory with landscape paintings and scenes of Italian life, such as Peasants of the Roman Campagna (1844; priv. coll.). Small-scale experiments in fresco painting, ostensibly his reason for travelling, exist in the Victoria and Albert Museum, including Paolo and Francesca, a subject which became almost an obsession in many later versions. Watts executed one large-scale fresco at Careggi, still in situ, showing a scene from Medici family history inspired by the villa itself, The Drowning of Lorenzo de Medici's Doctor, a scene of animated energy and Romantic brio (1844–5). Sculpture first entered his repertory while in Italy as well. Essentially Watts absorbed the culture of Italy, both its past and present. He mixed with an international community at coffee houses such as the Caffé Doney, where he socialized with artists and expatriates; one, Count Cottrell, who acted as chamberlain to the duke of Lucca (and who can now be properly identified as the amateur artist Henry Cottrell), became custodian of many of Watts's works of art when he left in 1847. His contacts with English aristocrats, great connoisseurs, and continental artistic society expanded his horizons immeasurably. Watts travelled with Lord Holland back to London for a few days in autumn 1844, but on returning to Italy went to Rome, Naples (where the Hollands had another residence), Pompeii, Milan, and Perugia. In 1845 he visited Lucca with Cottrell.

The latter portion of Watts's stay in Italy revolved around work on two history paintings in the large studio at Careggi, where he carried on even after Lord Holland resigned his diplomatic post and left Florence with his wife in 1846. Withdrawing from social life in town, Watts mixed mainly with the Duff Gordon sisters (whose mother, Lady Duff Gordon, had rented the Villa Careggi). He corresponded with Alexander Ionides in London, and a plan evolved for a commission to paint a large historical work destined for the university in Athens, with Watts explaining in a letter of June 1846 his aim ‘to tread in the steps of the Old Masters’ (Watts, Annals, 1.76). The plan foundered, yet the episode marked an important moment in the artist's career as his philhellenistic instincts and adoration of Phidias combined, albeit at this stage in the genre of history painting. Instead, in 1847, Watts prepared to enter the most recent of the series of competitions announced for the new houses of parliament with Alfred Inciting the Saxons to Prevent the Landing of the Danes by Encountering them at Sea (houses of parliament). Choosing a subject from English history with obvious nationalistic sentiments for one of his entries, Watts nevertheless proclaimed Phidias as his inspiration for a heroic style. Watts left Florence in mid-April 1847 to bring this painting and others back, fully intending to return to Italy; instead he remained based in London.

Watts at mid-career: changing direction in the late 1840s and 1850s

Winning another first premium of £500 confirmed Watts's status as a history painter. In addition, the Fine Arts Commission purchased Alfred Inciting the Saxons for a further £200. Despite winning a premium, Watts received no immediate commission to paint fresco decorations in the new Palace of Westminster. It is likely that he was seen as an outsider, who had not stayed within the academy and its circle. Some sections of the art world expected Watts to take the lead as a history painter, but in the wake of B. R. Haydon's suicide in 1846 this genre was undergoing a re-evaluation. Thackeray, writing as Michelangelo Titmarsh, caricatured misguided artistic aspirations in ‘Our Street’ with the character of George Rumbold, a thinly disguised spoof of his friend Watts.

Watts assumed some responsibility for the support of his half-sisters on returning to London, eventually obtaining a house for them in Long Ditton, Surrey. He lodged at 48 Cambridge Street until 1849. The eminent collector and connoisseur Robert Holford lent him studio space in Dorchester House on Park Lane while it was under construction. Here Watts painted ambitious large works, including Time and Oblivion (c.1848–9, exh. RA, 1864; priv. coll.), one of his most difficult subjects, part allegory, part Watts's own invention. The massive canvas did not go to public exhibition at this point, but was well enough known for another of Watts's new friends, John Ruskin, to borrow it. Although occupied with the young Pre-Raphaelites, Ruskin tried to guide Watts as well, with no success, yet they did discuss the aims of art. Watts wrote to him (c.1850): ‘my own views are too visionary and the qualities I aim at are too abstract to be attained, or perhaps to produce any effect if attained’ (Watts, Annals, 1.91).

To further his career, Watts relied on annual exhibitions and on his influential friends. Over the next few years he unveiled several large paintings in a poetic spirit, including Life's Illusions (exh. RA, 1849; Tate collection), with only varying success. His falling spirits and ill health fed into a series of social realist canvases depicting problems of Victorian society at the time (The Irish Famine and Found Drowned, c.1848–50; both Watts Gallery, Compton, Surrey) but also reflecting his own depressed state of mind. These works did not appear at public exhibitions and were instead on view in his studio for his own circle to see. They relate closely to the modern life paintings by the Pre-Raphaelites, who admired Watts's originality. His sympathy with younger artists led him in 1850 to act as teacher to a young Oxford student, John Roddam Spencer-Stanhope, a grandson of the earl of Leicester.

By now living and working in Mayfair near Berkeley Square, London, Watts shared his studio at 30 Charles Street with his friend Charles Couzens, a miniature painter whose portrait of the artist (c.1848; Watts Gallery, Compton, Surrey) depicts Watts alongside casts of the Parthenon frieze. There he met Sara Prinsep and her husband, Thoby, a retired East India Company official, who were neighbours. Outside the public arena, Watts moved freely in their bohemian circle. In 1849 he became infatuated with Sara's beautiful sister, Virginia, another of the eight extraordinary Pattle sisters, many of whom featured in Watts's paintings at this time. In October 1850 Virginia married Charles, Viscount Eastnor (third Earl Somers from 1853); a trip to Ireland late in 1850 with the poet Aubrey de Vere provided distraction for Watts in the wake of the marriage and allowed him to see the country he had so movingly depicted in The Irish Famine. Yet it should be noted that he stayed in the upper echelons of Irish society at the de Vere seat, Curragh Chase in co. Limerick.

It was a major turning point in Watts's career when, in 1850, he sent The Good Samaritan (Manchester City Galleries) to the Royal Academy with the explanation that it was ‘painted as an expression of the artist's admiration and respect for the noble philanthropy of Thomas Wright of Manchester’ (Watts, Annals, 1.130). When the academy's hanging committee positioned the painting poorly, Watts took it as an insult and for some eight years he ceased sending important subject paintings to the Royal Academy, using it initially for his lesser productions, chiefly portrait drawings; he did not exhibit anything at all there from 1853 to 1857. He stage-managed his return in 1858 with the ruse of sending his contributions under an assumed name, F. W. George. With so many colleagues and friends in art circles, Watts could not disguise his paintings, yet the event reflects his uneasy relationship with the Royal Academy as an institution.

Watts helped his new friends the Prinseps by persuading his erstwhile benefactors, the Hollands—now back in London—to grant them a 21-year lease on the dower house, Little Holland House, from 25 December 1850. Mirroring his experiences in Florence, Watts soon moved in with the Prinseps as guest and resident artistic luminary, becoming the central attraction in Sara's salon, prompting her famous remark: ‘He came to stay three days; he stayed thirty years’ (Watts, Annals, 1.128). He had private studio space, but the relaxed atmosphere of family life lifted his depression and provided him with a comfortable, even cosseted lifestyle. At about this time, Sara dubbed Watts Signor, a nickname that reflected his courteous manner and alluded to his years in Italy. Thereafter most intimate friends addressed him this way; he even grew into the image by adopting a skullcap, seen in many of his self-portraits. Suffering from frequent headaches, he seems to have decided ill health was to be a way of life. Serious-minded about more than his art, Watts did not encourage ‘anything savouring of the free and easy’, according to William Michael Rossetti (Rossetti, 1.204), yet he relaxed completely in the company of strong women and little children.

Watts's Charles Street studio remained a meeting-place, even when he left and his friend the painter Henry Wyndham Phillips took it over. Late in 1852 it became the home of the newly formed Cosmopolitan Club. Here Watts mixed with a wide range of intellectuals, writers, artists, and politicians with his own large paintings on permanent exhibition, including Echo(exh. houses of parliament competition, 1847; Tate collection) as a backdrop to the literary evenings there. The group included close friends of Watts such as Ruskin, the architect Philip Charles Hardwick, Tom Taylor, and Henry Layard. Mixing with this group encouraged Watts to formulate a plan to paint portraits of eminent men of the day for his own collection eventually destined to be presented to the nation (a gesture perhaps inspired by Turner, who died in 1851). Watts painted these portraits for his own collection over the next fifty years. His intention to bestow them on the nation became a regular talking point in the press during his life. Watts never named this collection but it came to be called the Hall of Fame.

Mural projects, travel, and public statements on art in the 1850s

Watts's allegiance to Italy prompted a short trip there in 1853 when he finally travelled to Venice in company with young Stanhope. Here for the first time he saw the glories of Venetian colour in painting. Further travels included several months in the winter of 1855–6 in Paris, where he took studio space on the rue des Saints Pères near the Seine on the Left Bank. For Lord Holland, then posted in France, Watts painted Adolphe Thiers, Prince Jérôme Bonaparte, and Princess Lieven (all priv. coll.), unexpected exercises in a style of sophisticated continental portraiture rarely attained by his English contemporaries.

Watts's talent for friendship testifies to his own natural behaviour and belief in himself and his work. His great friend Tom Taylor invited Watts to contribute to his life of Haydon in progress during 1852 thanks to Watts's already recognized position as an ‘eloquent advocate of the claims of High Art’ (Taylor, 3.361). He contributed to the first and second editions ofThe Life of Benjamin Robert Haydon, Historical Painter (1853). This text was the first of his many public pronouncements on art. Though ostensibly writing about Haydon, Watts extended the discussion to the idea of ‘awakening a national sense of Art’ (ibid., 3.372). For this he advocated large-scale wall paintings in fresco to adorn public buildings, with the sponsorship of the government. As an advocate for the public role of art, Watts attracted the attention and friendship of eminent individuals, such as Ruskin, Henry Acland of Oxford, and Layard, as well as younger up-and-coming men, including Charles Newton of the British Museum, who helped with various projects.

With Newton, Watts indulged his passion for the classical Greek sculptor Phidias, eventually travelling to Greece with Newton in October 1856. Watts accompanied his friend's expedition (sponsored by the government and the British Museum) to locate and excavate the site of the ancient mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world (concluding in spring 1857). Travelling via Constantinople and the Greek islands, the artist witnessed antique sculptures, as they were unearthed, complete with original colouring which, once exposed to the air, rapidly faded. Such transitory effects fuelled Watts's later reinterpretation of classical subjects.

Through the contacts he made at Little Holland House, meeting the Tennysons, the Pre-Raphaelites, and others, Watts found much work as a portrait painter, but he also pursued his other ambitions. By November 1852 he finally received a commission to paint a mural in the new Palace of Westminster. In the Upper Waiting Hall (the ‘Poets' Hall’) Watts and five other artists were allocated authors from whose work they chose a subject to fill six upright spaces of about 10 feet in height. Watts painted a scene from Spenser's Fairie Queene, The Triumph of the Red Cross Knight, also known as St George Overcoming the Dragon (restored).

Mural decoration amounted to an obsession with Watts. He painted some strictly decorative additions to a scheme at old Holland House (c.1849) in the Gilt Room and Inner Hall. At Little Holland House (c.1851–3) he had more freedom and painted a series in the dining-room prefiguring his later ‘symbolical’ works. One commission led to another: Lord and Lady Somers invited him to decorate their London town house, 7 Carlton House Terrace (c.1854–5). Not an exact scheme, but described by a contemporary writer as ‘the Gods of Parnassus and Olympus’ (Stephens, 47), these vigorous wall paintings evoke the baroque decorations of Italian palazzi. The scheme is also an important landmark in a more imaginative use of classical subject matter in English art. Further private commissions followed, including the two murals Achilles Watching Briseis Led Away from his Tents (1858; Watts Gallery, Compton, Surrey) and Coriolanus (1860, ex Christies, 25 June 1998) painted for Bowood, Wiltshire, for the third marquess of Lansdowne.

Watts advocated mural painting for public buildings in the 1850s as ‘a means of developing these qualities which would place British artists by the side of British poets, and form a great national school’ (Watts, Annals, 1.135). His most ambitious plan, conceived in late 1852, to paint a massive mural, ‘The Progress of Cosmos’, in the great booking hall at Euston Station, never progressed beyond a proposition he made, with the backing of P. C. Hardwick, his good friend and the architect involved. The directors of the London and North Western Railway Company rejected his plan, despite the fact that he wanted payment only for materials. More successfully, in 1852, Watts offered to paint a mural at the Great Hall of Lincoln's Inn, proposing his plan to the benchers, again with Hardwick's support. Completed in October 1859, Justice: a Hemicycle of Lawgivers won him praise in the press. His own programme depicting legal innovators throughout history must have required considerable reading and planning. It was not a true fresco and suffered some deterioration and restoration over the years. However, Justice remains Watts's most successful and most public mural, and a grand dinner in April 1860 along with a gift of £500 for his efforts sealed the triumph. One further public project in London, his last mural, was painted for the church of St James-the-Less, Pimlico (1861), depicting The Saviour in Glory (later replaced with a mosaic).

The 1860s

During this extremely productive decade, Watts's social life intersected with his art. For several years running he spent a few winter months at Sandown House, Esher, Surrey, with Thoby Prinsep's sister, at gatherings that included Tom Taylor and the Duff Gordons. The émigré Orléans family at nearby Claremont added to the social mix. A keen rider, Watts hunted with the Old Surrey foxhounds and the duc d'Aumale's harriers. Like his friend Frederic Leighton, he found continental society congenial. Little Holland House still formed the centre of his world, with Tennyson becoming a firm friend and the subject of a series of masterly portraits, including the ‘Moonlight’ portrait (priv. coll.), which exemplifies Watts's new, more ‘poetic’ interpretation of his sitters in a richer style inspired by Venetian art.

Tom Taylor introduced two young actresses, Kate and Ellen Alice Terry (1847–1928), to the Little Holland House circle in Kensington. For Watts personally, the meeting with Ellen Terry changed his life. Taken with her youthful spirit and fresh looks, he apparently first thought of adopting the sixteen-year-old girl; then, with the encouragement of Taylor and Sara Prinsep, Watts and Ellen became engaged. They married at St Barnabas Church, Kensington, on 20 February 1864, three days before Watts's forty-seventh birthday and a week before Ellen's seventeenth. However she did not fit easily into the Little Holland House circle, though her image inspired Watts in several paintings, including Choosing (RA, 1864; NPG). The marriage (if it was ever consummated) did not last; they separated in 1865, with Watts agreeing to pay her £300 a year ‘so long as she shall lead a chaste life’ (Loshak, ‘Watts and Ellen Terry’, 480). Ellen returned to her family and to the stage (somewhat embarrassingly for the artist, she appeared on playbills as Mrs G. F. Watts). In 1868 she left London to live with the architect E. W. Godwin, temporarily retiring from the stage to have a family.

Watts moved more emphatically into the public realm with successes such as the Lincoln's Inn mural to his credit. He returned to the forum of the Royal Academy, even though not yet a member of this institution. This exclusion gave rise to public comment at a time of growing dissatisfaction with the academy, culminating in a government inquiry led by a select committee in 1863. Watts testified himself, offering another cogent public statement on art, focusing on improvements to life drawing in the schools, showing models in action. He objected to the idea of an artist putting himself up for election to the academy. Four years later, under newly revised rules, Watts's name went forward without any intervention by him. Elected associate of the Royal Academy on 31 January 1867, he was quickly elevated to full membership on 18 December of the same year—a unique event in the academy's history and an indication of the esteem in which fellow artists held him. In a position to take on academy duties, such as hanging exhibitions (which he did in 1869), he came into even closer contact with Leighton, his close friend (and Kensington neighbour since 1866).

Portraiture occupied much of Watts's time, not only commissioned works such as grand-manner portraits, Hon. Mrs. Percy Wyndham (late 1860s; priv. coll.) and Lady Bath (begunc.1862; priv. coll.), but also portraits of sitters of his own choosing, for example, William Gladstone (1859, exh. 1865), Dean Henry Milman (c.1863), Robert Browning (1866), andAlgernon Swinburne (1867, NPG), retained for his own gallery of worthies. He ventured into new types of subject matter with poetically inspired paintings finally appearing at public exhibitions, encouraging younger artists. Designs under way by the late 1860s included early versions of The Court of Death, Time, Death and Judgement, and Old Testament subjects, such as The Creation of Eve and The Denunciation of Cain. Supportive patrons such as Sir William Bowman, the London oculist, and Charles Rickards, a well-to-do philanthropist from Manchester, sought out Watts and his work, providing avenues for his more experimental subjects. Indeed, the upturn in Watts's increased sales encouraged him at one point, about 1869–70, to engage the dubious entrepreneur Charles Augustus Howell as an unofficial agent.

Eminent men crossed Watts's path and became supporters. Gladstone, in sympathy with Watts's modern ‘classical’ works, requested paintings from him and gave tangible support to his ideas for bequeathing his work to the nation. Dean Milman interceded for commissions to participate in the scheme to decorate St Paul's Cathedral, but although Watts produced designs (c.1861–2, St John; St Matthew), along with Alfred Stevens, the scheme dragged on until mosaics after his two designs went into position much later. Watts devoted more time to sculpture both as an aid to composing and in its own right. His first tomb monument was to Thomas Cholmondely Owen (1867; Condover church, Shropshire). The marble bustClytie (exh. RA, 1868; London, Guildhall) stands as a testament of his own reinterpretation of the spirit of Phidian art, revealing a new freedom of movement to younger sculptors. Its appearance at the Royal Academy led to further commissions for sculpture. The long illness of his friend William Kerr, eighth marquess of Lothian, had already inspired early versions of Love and Death; after Lothian's death in 1870 Watts executed a recumbent memorial figure (Blickling church, Norfolk) characterized by deep cutting and expressive carving, also seen in the monument to the bishop of Lichfield (commission 1869, Lichfield Cathedral). He also collaborated with J. E. Boehm on the full-length seated statue of the first Lord Holland (Holland Park) at about this time. He transformed the equestrian figure of Hugh Lupus for the marquess of Westminster (1870–84; priv. coll.) into Physical Energy, which became his best-known sculpture. The first version later formed part of the memorial to Cecil Rhodes in South Africa.

The 1870s

With Lady Holland selling off sections of the Holland estate, Watts foresaw a departure from Little Holland House within the next few years. In late 1871, he bought property on the Isle of Wight, where Julia Margaret Cameron and Tennyson already had homes. Near Freshwater, Watts had The Briary built for the Prinseps by the autumn of 1873. His connections with them led him to adopt their young relation Blanche Clogstoun (later Somers-Cocks), who featured in several of his paintings in the 1870s. This gesture seemed to be his way of creating a family, as the Prinsep children grew up and left. Before 1875, when Little Holland House was knocked down, he bought a parcel of land, number 6 on the new Melbury Road, backing on to Leighton's property, and commissioned C. R. Cockerell to build a home and studio, complete with a top-lit gallery to display his collection. He moved into New Little Holland House in February 1876. His neighbour, Emilie Barrington, an amateur painter, writer on art, and friend of artists, made herself indispensable to Watts, along with her husband, Russell, who for a while acted as a financial agent for the artist. At about this time, Watts discovered that his wife had some years earlier set up home with Godwin. He petitioned for divorce (perhaps at her instigation); the case appeared before the Probate, Divorce, and Admiralty Division on 13 March 1877 and a decree nisi was awarded. Soon after, Ellen remarried.

Watts embarked on a wide range of commissions to pay for building projects, stepping up his portrait work with reluctance. However, ongoing patronage meant he could also paint large subject paintings and find purchasers. His professional stature as a full academician also helped considerably. For his diploma piece, he painted on life scale a multi-figure composition, The Denunciation of Cain (exh. RA, 1872; RA). He saw it as part of a cycle of paintings which (much later in the 1890s) eventually came to be called The House of Life(not Watts's own title). This grand scheme never materialized, but he continued to paint oils derived from it, presenting them as independent works. He insisted that ‘these I always destined to be public property’ (Watts, Annals, 1.261). He exhibited early versions of The Titans (later called Chaos), his own personal reworking of earth's origins, combining a post-Darwinian perspective with a partly invented variation on classical myth. Smaller exhibition venues, such as the Dudley Gallery, provided convenient places to show experimental works, such as early versions of Love and Death, as well as works in progress. To the Royal Academy Watts generally sent portraits, considering that venue as ‘no place for a grave, deliberate work of art’ (Bryant, ‘Watts at the Grosvenor Gallery’, 109). He worked through several compositions, such as Time, Death and Judgement and The Court of Death, from the 1860s onward, increasing the scale of these works and refining the imagery during the 1870s. His method involved reworking compositions on a more and more monumental scale and with varying qualities of mood and changes in colour. With the volume of work increasing, Watts took on assistants, including Matthew Ridley Corbet and, in the 1880s, Cecil Schott, who carried out preliminary work on his larger canvases.

With the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery in May 1877, Watts found his ideal venue where he showed his work for the next ten years. His friend Coutts Lindsay, owner of the gallery, included him as one of the featured artists who sent in several paintings. The triumphant appearance of the prime version of Love and Death (Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester) marked the first time Watts's ‘symbolical’ paintings were revealed to the public as he intended. This turning point in his reputation saw critical and public favour—particularly that of the artistic élite—heaped upon him. The prime version of Time, Death and Judgement (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa) followed in 1878 to equal acclaim. His art travelled abroad to international exhibitions, particularly the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1878, where Love and Death among his other works earned a first-class medal. In 1879, along with a handful of internationally celebrated British artists, Watts was asked by the Uffizi Gallery to paint a Self-Portrait (exh. RA, 1880) for their gallery of artists' portraits, a request to which he acceded with enthusiasm. His stature increased not only with such international recognition, but also with further writings and statements on art at conferences and in periodicals.

The 1880s

In 1880, with his reputation secure, Watts published ‘The present conditions of art’ in a literary journal, the Nineteenth Century. In this article he complained about the Royal Academy, its commercial spaces being unsuited to his ‘poems painted on canvas’ (Bryant, ‘Watts at the Grosvenor Gallery’, 109). Even more tellingly, he spoke of art as a way to ‘lift the veil that shrouds the enigma of being’ (Bryant, ‘Watts and the symbolist vision’, 73), forecasting symbolist concerns of the 1880s. His imaginative subject paintings dominated the Grosvenor Gallery: taking classical culture as the point of departure in Orpheus and Eurydice (exh. Grosvenor Gallery, 1879; Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad, India) and Endymion(c.1869, exh. Grosvenor Gallery, 1881; priv. coll.), the artist explored other levels of meaning, introducing ideas of death, mysticism, and spiritualism, that fuelled symbolism in contemporary art both at home and abroad, providing an example for a younger generation of artists.

A key indication of Watts's ascending position was the exhibition of Rickards's collection of works by Watts staged at the Royal Manchester Institution in 1880. This event, in turn, led to Coutts Lindsay's decision to stage an even more ambitious event in the winter of 1881–2. Containing more than 200 works, the Collection of the Works of G. F. Watts, R.A. has the distinction of being the first full retrospective of any living British artist. By now into his sixties, Watts had a full career behind him, well worth examining. His introduction to the catalogue defined a type of painting he dubbed ‘symbolical’—non-narrative works with a poetic spirit. His status as an inspiration to a younger generation and as a British artist seen in an international context (thanks to the ties between the Grosvenor Gallery and the Paris art world), contributed to the cult of the artist as a personality, a relatively new idea in the late nineteenth-century art world. His work became well known abroad, on exhibition in the Paris Salon of 1880.

After 1880 Watts's art was continually on view as he took the presentation of his art into his own hands, further enhancing his reputation. His own picture gallery opened at New Little Holland House, free to the public on Saturday and Sunday afternoons. He lent or gave his works to London institutions (Time, Death and Judgement to St Paul's Cathedral; a selection of works lent to the South Kensington Museum in the 1880s). An exhibition entitled the ‘Watts collection’ travelled to various cities throughout Britain during the mid-1880s. He presented paintings to institutions abroad, for example Time, Death and Judgement to Canada in 1886; versions of Love and Life to the USA in 1893 (sold from the national collections in 1987), and to France (now Musée d'Orsay, Paris). In 1884, with the encouragement and help of a young American, Mary Gertrude Mead, who later married Edwin Austin Abbey, Watts showed a group of some thirty works at New York's newly opened Metropolitan Museum of Art. Although he did not travel himself to New York, Watts took a unique step in promoting his work abroad through a one-man exhibition. The event placed contemporary British art on the map in America with the first ‘blockbuster’, open for six months.

In the wake of the Grosvenor Gallery retrospective of 1882–3, Watts received a range of honours: Oxford made him a DCL and Cambridge awarded an honorary degree of LLD in 1882 ‘in recognition of his distinguished services to art’. In 1885, when Gladstone, as prime minister, offered baronetcies to Watts and J. E. Millais, Watts declined on the grounds that he felt his financial means insufficient for the role; Gladstone persisted but his offer was rejected again in 1894. Further recognition came in 1886 with the government indicating that it would accept his bequest of paintings in due course.

During the 1880s Watts exhibited paintings now considered as a distinctly British contribution to international symbolism, such as his own invented subjects, Hope (exh. Grosvenor Gallery, 1886; first version, priv. coll.) and the enigmatic Dweller in the Innermost (exh. Grosvenor Gallery, 1886; Tate collection), a personification of the idea of conscience. Such paintings reflect Watts's own thinking on a variety of ideas never before considered subject matter for painters. He grappled with these notions, as did like-minded men such as his friend Frederic Myers, founder of the Society for Psychical Research, a group Watts joined as an honorary member in 1884.

Watts remarried on 20 November 1886 in Epsom, Surrey. Mary Seton Fraser-Tytler (1849–1938), aged nearly thirty-seven, the third daughter of a Scottish gentleman from Inverness-shire, Charles Edward Fraser-Tytler of Balnain and Aldourie, had studied art in London since the 1860s and worshipped Watts; she moved into his circle through the Freshwater community, especially J. M. Cameron. According to Holman Hunt, Watts had several ladies pursuing him at this time. His decision to wed Mary, surprising to many friends, seems to have been dictated by his age (sixty-nine), increasingly poor health (rheumatism had set in by 1883), and the need for a sympathetic person to take charge of the household. Honeymooning in the winter of 1886–7, they travelled to Egypt, including the Nile, as well as to Constantinople, Athens, and Messina. The Greek portion of the journey enabled him for the first time to see the monuments of the Acropolis in their own surroundings. Mr and Mrs Watts returned via Paris, and eventually home to Kensington in June 1887. Further international travel followed the next winter, as the ageing Watts sought to escape damp London winters for warmer climes. November 1887 found them in Sliema, Malta: Mediterranean light and colour fed into Watts's art in a series of evanescent seascapes such as Fog off Corsica (exh. New Gallery, 1889; priv. coll.). On the return journey in February 1888 they visited the alpine regions of Haute-Savoie; the scenery of the high Alps inspired several visionary landscapes including Sunset on the Alps (1888–94; Watts Gallery, Compton, Surrey).

Social concerns continued to preoccupy Watts. In September 1887 he wrote to the national press proposing a record of heroic deeds of common people as a fitting jubilee memorial. He also formed a close friendship with Canon Samuel Barnett and his wife Henrietta, who were active in helping the poor in the East End of London at their church, St Jude's, Whitechapel; when art exhibitions became part of their programme from 1885, Watts readily lent his paintings. Works such as Mammon (1884–5; Tate collection), a statement on the horrors of worshipping money, revealed the artist's social impulse in symbolist visual imagery.

Watts valued his artistic friendships, often seeking the opinions of his colleagues in connection with progress on individual paintings. In addition to his friends Burne-Jones and Leighton, he particularly (and rather unexpectedly) sought out Briton Riviere, Henry Holiday, Walter Crane, and William Blake Richmond. Support for worthy causes led to writing, including the preface to A. H. Mackmurdo's Plain Handicrafts in 1892, and to financial contributions to the Home Arts movement beloved by his wife, by now a craftswoman in her own right.

In the late 1880s Watts's art assumed an even higher position in public and critical estimation. In 1887 M. H. Spielmann wrote a substantial article in the Pall Mall Gazette based on conversations with the artist, including a catalogue of his work. Watts's powers were at their height. He worked on the large version of The Court of Death (c.1868–1903; Tate collection). Portraits such as the masterly Cardinal Manning (exh. Grosvenor Gallery, 1882; NPG) reveal an ability to penetrate the character of his sitters. In 1888 he switched allegiance from the Grosvenor Gallery to the newly formed New Gallery, along with Burne-Jones. Here his major works appeared until his death; yet he contributed to a wide range of exhibiting venues, including the Royal Society of British Artists, the Society of Portrait Painters, and the Grafton Gallery. Internationally, Watts and Burne-Jones triumphed at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1889. Watts showed eight works, including Hope and Mammon, recognized by the French critics as ‘allégories poétiques’ (Bryant, ‘Watts and the symbolist vision’, 76).

From the 1890s to 1904

In 1890, encouraged by his friend Andrew Hichens, Watts agreed to the purchase of land in Compton, near Guildford, in Surrey, for a house to be built by Ernest George. Watts and his wife named it Limnerslease, a combination of the word ‘limner’, meaning artist with ‘leasen’ or glean. Watts bought it by 1891, obtaining the freehold from Hichens in 1899. Still based in Kensington, he continued to work on a massive sculpture, Physical Energy, as well as a large statue of Tennyson (1898–1903) for the city of Lincoln. Ill health punctuated the decade but he still produced an enormous amount for a man approaching eighty. Travel to Scotland in 1898 inspired landscape paintings. By 1890 he and Mary were introduced to a young orphan, Lilian (also known as Lily) Mackintosh (later Mrs Michael Chapman), who later came to live with them. She eventually became heir to the entire estate left by Mrs Watts.

Watts's international profile meant visits from admirers from abroad. In autumn 1890 his conversations with the queen of Romania inspired his thinking about the painting Sic transit(1890–92; Tate collection), a symbolist memento mori produced at a time when Watts himself suffered a severe illness. In 1893 a visit from Léonce Benedite, the director of the Luxembourg (a collection of modern paintings) in Paris, led to his choice of a version of Love and Life, which Watts presented to the French nation. In the same year twenty-four paintings and one sculpture travelled to an exhibition in Munich, with the Bavarian government purchasing The Happy Warrior (exh. Grosvenor Gallery, 1884; Bayerische Staatsgemäldegalerie, Munich).

Watts's celebrity status resulted in numerous articles in the British press, including interviews filled with photographs of the artist at work and at rest. His personal regime, always rather abstemious, became even more regulated as he followed the ‘Salisbury diet’, consisting of small amounts of nearly raw meat, toast, and milk, with no fruit or vegetables. A hearing aid improved his increasing deafness. In December 1891 the caricature by Spy in Vanity Fair showed the snowy-haired Watts in frock coat and Titian-like skullcap, along with the quotation ‘He paints portraits and ideas’, summing up his popular image. His pamphlet What Should a Picture Say in 1894 indicated his continuing concern that his paintings should be widely understood. He drove a hard bargain with the many new clients seeking his paintings for their collections, asking upwards of £2000 for large subject paintings and £500 for landscapes in 1895.

To control the publication of his work, Watts retained copyright of his paintings. His working relations with the art photographer Frederick Hollyer also ensured that most of his paintings existed in black and white photographs advertised regularly for easy ordering. This steady supply also enabled the press to produce well-illustrated articles. By 1900 more than a dozen of these articles had appeared, embedding Watts's work in the popular imagination. With the death of many of his closest friends by this time, he became by default the most famous living British painter. Although officially retiring from the Royal Academy, taking on the title of honorary retired academician from November 1896, Watts still sent paintings to a whole range of exhibition venues until his death.

Watts's long-planned bequests to the nation finally came to fruition in the late 1890s. In 1895 the National Portrait Gallery received a group of portraits; in 1896 Watts became a trustee. In 1897 the new National Gallery of British Art, popularly known as the Tate Gallery, after its benefactor, opened with seventeen paintings forming the first instalment of the Watts Gift. Specially displayed in two rooms (later one), this bequest formed a significant portion of the new gallery. By the late 1890s Watts's paintings were more widely available in London than those by any other living artist. Another retrospective exhibition was held at the New Gallery in 1896–7, with Watts writing a preface to the catalogue. Friends marked his eightieth birthday in February 1897 with a congratulatory address signed by several hundred distinguished men and women of the day, and including a specially composed tribute from Swinburne—‘High Thought and Hallowed Love’. In 1900 the memorial to heroes in everyday life, funded by Watts, took the form of a canopied area decorated with Doulton tiles in part of the old churchyard of St Botolph, Aldersgate (in the Postman's Park) in the City of London. The crowning moment of his career came in 1902, when Edward VII instituted the Order of Merit with Watts among the inaugural twelve.

Watts's intellectual vigour produced more original compositions about 1900, including the startlingly visionary Sower of the Systems (exh. New Gallery, 1903; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto) along with Progress and Destiny (c.1903/1904, both Watts Gallery, Compton, Surrey). Such works embraced the new century, as Watts, ever conscious of his impact on posterity, initiated his own dialogue with future generations. The Court of Death was completed in 1903 when, after decades of work, it finally went to join the Watts Gift at the Tate Gallery. His bronze version of Physical Energy went on view at the Royal Academy in May 1904, prior to being sent to South Africa as a memorial to Cecil Rhodes.

In 1902 Watts bought a further 3 acres in Compton, across the road from his house, with the intention of building a separate picture gallery. Opening in April 1904, this building is the home of the Watts Gallery, where Mrs Watts presided as ‘keeper of the flame’ until her death in 1938. Overall, she was far from a benign influence, distancing him from certain friends. Her plan for a mortuary chapel for the village, designed and decorated by herself, complete with nearby memorial to Watts, served as a constant reminder of his approaching death. After 1904 she nurtured the Watts legend, sometimes distorting evidence, which she published in the long-gestating Annals of an Artist's Life in 1912. Her lack of information about his career before 1886 has also caused problems of dating and of chronology; her compendious manuscript catalogue of his works (Watts Gallery) is often unreliable.

The illness that finally caused his death started in early June 1904 while Watts worked on the gesso model of Physical Energy in Kensington. He died at 6 Melbury Road on Friday 1 July with the cause recorded on his death certificate (dated 2 July) as ‘cystitis with high fever, from old septic absorption’, along with bronchitis and a weakened heart. The obituary inThe Times opened with the declaration, ‘the most honoured and beloved of English artists is dead’ (2 July, p. 5). Such was the importance of the event that the sermon in St Paul's Cathedral two days after his death focused on the artist. The next week, on 4 July, a train to Brookwood conveyed his body for cremation ‘at Mr. Watts's express wish’. The ashes went to Compton for eventual interment in the cemetery adjacent to the mortuary chapel. A memorial service took place in London at St Paul's Cathedral with dignitaries, as well as friends; the funeral was held at Compton on Friday 8 July. Watts's will named some specific bequests of individual portraits to friends, and a group of drawings to the Royal Academy, but left virtually everything else in the hands of his executors headed by his wife. She cannily queried some unclear wording in the will which enabled her and the other executors to bestow most of his works on the Watts Gallery, rather than to public museums throughout Britain, as the artist intended. The gallery, somewhat depleted by sales over the years, remains an important collection of the artist's work.

Watts's posthumous reputation flowered for a decade, with a series of memorial exhibitions in 1905–6 and a flood of publications. In 1905 Charles Stanford, who had composed some accompanying music for the funeral, wrote his symphony no. 6 in E[flat] major ‘in honour of the life-work of a great artist: George Frederic Watts’. With the era of modernism, the artist's reputation plummeted as the Tate Gallery closed the room devoted to his work by the late 1930s. Yet Watts lived on in the collective memory of Bloomsbury thanks to his friendships with the Prinseps and Stephenses, even if this survival became the subject of humour rather than respect, as in Virginia Woolf's short play, Freshwater (1923) which mercilessly lampooned Watts, Tennyson, and Mrs Cameron. His appeal to the literary world continued: Watts's memorial to unsung heroes in the Postman's Park took an integral role in the play Closer (1997) by Patrick Marber.

Watts's portraits have always sustained his position as one of the major figures of the nineteenth century. His role as an innovator in international symbolism is now acknowledged. Watts is essentially important as an artist who, in the course of the century, transformed the ideals of ‘high art’ which he inherited in the 1830s into an original visual language of universals for a range of genres. Equally important is the way Watts's life and career epitomized the modern notion of the artist as celebrity and hero.

Barbara Coffey Bryant DNB