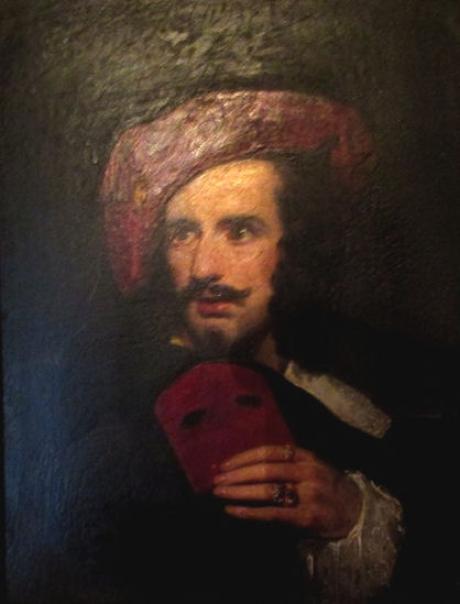

There are 2 known portraits of William Charles Macready in public Collections by John Jackson the first portrait is in the National Portrait Gallery showing the actor in his role as Shylock in the Merchant of Venice and a Portrait in the Royal Shakespere Collection as Macbeth (from 'Macbeth', Act II, Scene 2) both painted in 1821 and this newly discovered portrait. Actors have since the ancient Greeks been represented holding a Mask. Masks have been used almost universally to represent characters in theatrical performances. Theatrical performances are a visual literature of a transient, momentary kind. It is most impressive because it can be seen as a reality; it expends itself by its very revelation. The mask participates as a more enduring element, since its form is physical.

Masked Roman actors The mask as a device for theatre first emerged in Western civilization from the religious practices of ancient Greece. In the worship of Dionysus, god of fecundity and the harvest, the communicants’ attempt to impersonate the deity by donning goatskins and by imbibing wine eventually developed into the sophistication of masking. When a literature of worship appeared, a disguise, which consisted of a white linen mask hung over the face (a device supposedly initiated by Thespis, a 6th-century-bce poet who is credited with originating tragedy), enabled the leaders of the ceremony to make the god manifest. Thus symbolically identified, the communicant was inspired to speak in the first person, thereby giving birth to the art of drama.

In Greece the progress from ritual to ritual-drama was continued in highly formalized theatrical representations. Masks used in these productions became elaborate headpieces made of leather or painted canvas and depicted an extensive variety of personalities, ages, ranks, and occupations. Heavily coiffured and of a size to enlarge the actor’s presence, the Greek mask seems to have been designed to throw the voice by means of a built-in megaphone device and, by exaggeration of the features, to make clear at a distance the precise nature of the character. Moreover, their use made it possible for the Greek actors—who were limited by convention to three speakers for each tragedy—to impersonate a number of different characters during the play simply by changing masks and costumes. Details from frescoes, mosaics, vase paintings, and fragments of stone sculpture that have survived to the present day provide most of what is known of the appearance of these ancient theatrical masks. The tendency of the early Greek and Roman artists to idealize their subjects throws doubt, however, upon the accuracy of these reproductions. In fact, some authorities maintain that the masks of the ancient theatre were crude affairs with little aesthetic appeal.

In the Middle Ages, masks were used in the mystery plays of the 12th to 16th century. In plays dramatizing portions of the Bible, grotesques of all sorts, such as devils, demons, dragons, and personifications of the seven deadly sins, were brought to stage life by the use of masks. Constructed of papier-mâché, the masks of the mystery plays were evidently marvels of ingenuity and craftsmanship, being made to articulate and to belch fire and smoke from hidden contrivances. But again, no reliable pictorial record has survived. Masks used in connection with present-day carnivals and Mardi Gras and those of folk demons and characters still used by central Europeans, such as the Perchten masks of Alpine Austria, are most likely the inheritors of the tradition of medieval masks.

Harlequin (Arlecchino)The 15th-century Renaissance in Italy witnessed the rise of a theatrical phenomenon that spread rapidly to France, to Germany, and to England, where it maintained its popularity into the 18th century. Comedies improvised from scenarios based upon the domestic dramas of the ancient Roman comic playwrights Plautus (c. 254–184 bce) and Terence (c. 195–c. 159 bce) and upon situations drawn from anonymous ancient Roman mimes flourished under the title of commedia dell’arte. Adopting the Roman stock figures and situations to their own usages, the players of the commedia were usually masked. Sometimes the masking was grotesque and fanciful, but generally a heavy leather mask, full or half face, disguised the commedia player. Excellent pictorial records of both commedia costumes and masks exist; some sketches show the characters of Harlequin and Columbine wearing black masks covering merely the eyes, from which the later masquerade mask is certainly a development.

Except for vestiges of the commedia in the form of puppet and marionette shows, the drama of masks all but disappeared in Western theatre during the 18th, 19th, and first half of the 20th centuries. In modern revivals of ancient Greek plays, masks have occasionally been employed, and such highly symbolic plays as Die versunkene Glocke (The Sunken Bell; 1897) by German writer Gerhart Hauptmann (1862–1946) and dramatizations of Alice in Wonderland have required masks for the performers of grotesque or animal figures. Irish poet-playwright W.B. Yeats (1865–1939) revived the convention in his Dreaming of the Bones and in other plays patterned upon the Japanese Noh drama. In 1926 theatregoers in the United States witnessed a memorable use of masks in The Great God Brown by American dramatist Eugene O’Neill (1888–1953), wherein actors wore masks of their own faces to indicate changes in the internal and external lives of their characters. Oskar Schlemmer (1888–1943), a German artist associated with the Bauhaus, became interested in the late 1920s and ’30s in semantic phenomenology as applied to the design of masks for theatrical productions. Modern art movements are often reflected in the design of contemporary theatrical masks. The stylistic concepts of Cubism and Surrealism, for example, are apparent in the masks executed for a 1957 production of La favola del figlio cambiato (The Fable of the Transformed Son) by Italian dramatist Luigi Pirandello (1867–1936). A well-known mid-20th-century play using masks was Les Nègres (1958; The Blacks) by French writer Jean Genet. The mask, however, unquestionably lost its importance as a theatrical convention in the 20th century, and its appearance in contemporary Western plays is unusual.

In many ways akin to Greek drama in origin and theme, the Noh drama of Japan has remained a significant part of national life since its beginnings in the 14th century. Noh masks, of which there are about 125 named varieties, are rigidly traditional and are classified into five general types: old persons (male and female), gods, goddesses, devils, and goblins. The material of the Noh mask is wood with a coating of plaster, which is lacquered and gilded. Colours are traditional. White is used to characterize a corrupt ruler; red signifies a righteous man; a black mask is worn by the villain, who epitomizes violence and brutality. Noh masks are highly stylized and generally characterized. They are exquisitely carved by highly respected artists known as tenka-ichi, “the first under heaven.” Shades of feeling are portrayed with sublimated realism. When the masks are slightly moved by the player’s hand or body motion, their expression appears to change.

In Tibet (China), sacred dramas are performed by masked lay actors. A play for exorcising demons called the Dance of the Red Tiger Devil is performed at fixed seasons of the year exclusively by the priests or lamas wearing awe-inspiring masks of deities and demons. Masks employed in this mystery play are made of papier-mâché, cloth, and occasionally gilt copper. In the Indian state of Sikkim and in Bhutan, where wood is abundant and the damp climate is destructive to paper, the masks for performance of this play are carved of durable wood. All masks of the Himalayan peoples are fantastically painted and usually are provided with wigs of yak tail in various colours. Formally, they often emphasize the hideous.

Masks, usually made of papier-mâché, are employed in the religious or admonitory drama of China; but for the greater part the actors in popular or secular drama make up their faces with cosmetics and paint to resemble masks, as do the Kabuki actors in Japan. These makeup masks both identify particular characters and convey their distinctive personalities. The highly didactic sacred drama of China is performed with the actors wearing fanciful and grotesque masks. Akin to this “morality” drama are the congratulatory playlets, pageants, processions, and dances of China. Masks employed in these ceremonies are highly ornamented, with jeweled and elaborately filigreed headgears. In the lion and dragon dances of both China and Japan, a stylized mask of the beast is carried on a pole by itinerant players, whose bodies are concealed by a dependent cloth. The mask and cloth are manipulated violently, as if the animal were in pursuit, to the taps of a small drum. The mask’s lower jaw is movable and made to emit a loud continuous clacking by means of a string.

In the 20th century, the mask increasingly became perceived as chiefly a decorative object, although it has long been used in art as an ornamental device. In Haiti, India, Indonesia, Japan, Kenya, and Mexico, masks were produced largely for tourists. Masks continue to be of vital interest to ethnographers and artists alike. Masks also have exerted a decided influence on modern art movements, especially in the first decades of the 20th century, when painters such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and André Derain found a source of inspiration in the masks of Africa and western Oceania.

William Charles Macready,(1793–1873), actor and theatre manager, was born on 3 March 1793 at 3 Mary Street (now 45 Stanhope Street), Euston Road, London, the fifth of the eight children of William Macready or M'cready (1755–1829) and his first wife, the actress Christina Ann, née Birch (1765–1803). He was baptized at St Pancras parish church on 21 January 1796, when his date of birth was erroneously given as 1792. William Macready senior was the son of a prosperous Dublin upholsterer, with whom he served an apprenticeship before taking to the stage. Following provincial engagements in Ireland, he joined the Smock Alley Theatre in Dublin in 1785 to take over the part of Egerton to the Sir Pertinax McSycophant of the irascible and elderly (at least eighty-two) Charles Macklin in The Man of the World. Macklin used his influence to help Macready secure engagements in Liverpool and in Manchester, where on 18 June 1786 Macready married Christina Ann Birch at the collegiate church. Miss Birch came from genteel stock. Her grandfather, Jonathan Birch, was vicar of Bakewell in Derbyshire; two of her paternal uncles were clergymen; and her father, who died—badly off—when she was three, was a surgeon. On her mother's side she was descended from William Frye (d. 17 May 1736), president of the council of Montserrat.

On 18 September 1786 the elder Macready—again through Macklin's good offices—appeared at Covent Garden as Flutter in Hannah Cowley's The Belle's Stratagem; he remained in the company for ten years, never progressing from the ranks of supporting player, though he did enjoy some success as an adapter of old plays. Mrs Macready did not appear on the London stage. The couple's first three children died in infancy; their fourth child, Joanna, survived only until her seventh year, though she lived on in the memory of her younger brother William, whose birth in 1793 was followed by that of Laetitia in 1794 and Edward in 1798. While still a member of the Covent Garden company the elder Macready ventured into management, first at the Royalty Theatre, Wellclose Square, London, and next—in June 1795—at the newly opened theatre in New Street, Birmingham. Following a quarrel over his salary Macready left Covent Garden in 1797 and, after a further unsuccessful attempt at the Royalty, devoted himself to provincial management in Birmingham and beyond (Leicester, Sheffield, and Manchester), in support of which his wife resumed her stage career.

William Charles Macready was, in his own words, ‘got out of the way’ (Macready's Reminiscences, 2) and sent to school at an early age. When he was six he transferred from a preparatory school in Kensington to an establishment in St Paul's Square, Birmingham, where he distinguished himself by memorizing and reciting long extracts from Shakespeare, Milton, and Pope, marred only by his abuse of the letter ‘h’. In the school holidays his favourite recreations were performing some of his own compositions with his siblings and witnessing such luminaries as Thomas King, Sarah Siddons, and Elizabeth Billington performing in his father's theatre. On 3 March 1803 he entered Rugby School, where his mother's cousin William Birch was a master.

At the beginning of the Christmas holidays Macready was devastated by the news of his mother's death, which had occurred on 3 December 1803. His parents' motives in sending Macready to Rugby had been to educate him for a more respectable profession than the stage, which Macready told his headmaster, Dr Inglis, he very much disliked. Nevertheless, with his cousin Tom Birch, he absented himself from school to see the Infant Roscius, Master Betty, as Richard III in Leicester; Macready also assisted with (by borrowing books and costumes from his father) and performed in plays; and, under Inglis's successor, John Wooll, he won prizes for recitation and on speech day 1808 played the title role in the closet scene from Hamlet. That year Birch wrote to Macready's father of his son's ‘wonderful talent for acting and speaking’, which ‘may be turned to good account in the Church or at the Bar; it is valuable everywhere’ (Trewin, 22–3).

These hopes were dashed by the decline in the elder Macready's fortunes, as a result of which he withdrew his son from Rugby School at the end of 1808, Birch discharging the debt of over £100 for school fees. Though cut short, Macready's time at Rugby was immensely important to him throughout his life. It gave him the educational background—‘he knew enough Greek to astonish a dinner party with a quotation from Homer’ (Archer, 11)—to mix in cultivated society, and it fired him with a determination to elevate the stage to a status comparable to that of the other professions to which he had aspired.

Aged fifteen, Macready had to bide his time before making his professional acting début. He learned some juvenile roles in readiness and spent a short time in London, observing leading actors perform and taking fencing lessons, though this was a skill of which he never became master. Late in 1809 he was confronted with the task of salvaging the fortunes of his father's Chester company, which had not been paid for three weeks. Macready emerged—successfully—from the experience with the precepts about the hazards of theatrical management and the importance of financial probity which were to inform the rest of his career. By the summer of 1810 the elder Macready, who had spent a short time in prison for debt, was able to resume his Birmingham management, and it was there, on 7 June 1810, that William Charles Macready made his first appearance on any stage, as Romeo.

Macready's image as Romeo was captured in a portrait by Samuel De Wilde: a chubby-faced boy, in a costume including a broad flowered sash, almost under his armpits, an upstanding ruff, white kid gloves, white silk stockings and dancing pumps, and a large black hat with white plumes. After a faltering, mechanical start, Macready, encouraged by sympathetic applause from the audience, got the measure of his role and achieved what the audience, the critics, and the young actor himself recognized as a remarkable début. During the next four years as the juvenile lead in his father's company he played more than seventy different roles. In Newcastle upon Tyne early in 1811 he performed Hamlet, observing that ‘a total failure in Hamlet is a rare occurrence’ (Macready's Reminiscences, 37), and though, with a self-criticism which characterized him throughout life, he described his début in the role as ‘my crude essay’, it was pronounced a success. Also in Newcastle the young actor underwent the daunting experience of appearing opposite Mrs Siddons, as Beverley to her Mrs Beverley in Edward Moore's The Gamester and as Young Norval to her Lady Randolf in John Home's Douglas. Understanding and encouraging on stage and off, Mrs Siddons gave Macready some parting words of advice: ‘You are in the right way, but remember what I say: study, study and do not marry till you are thirty!’ (Archer, 21)—both of which injunctions he heeded.

Macready also performed with John Philip Kemble, Dorothy Jordan, and Charles Mayne Young; he adapted Scott's Marmion for his own benefit. Relations between father and son, who were both quick-tempered, became strained, and on 29 December 1814 Macready began an engagement in Bath, where his roles included Romeo, Hamlet, Hotspur, Richard II, and Orestes (in Ambrose Philips's The Distressed Mother). In the spring of 1815 Macready was in Glasgow and there he met—and scolded for not knowing her lines—a pretty nine-year-old girl, Catherine Frances Atkins (1803/4–1852), who was to become his first wife. In Dublin—in April 1815 and again in February 1816—Macready commanded a salary of £50 a week and was attracting the attention of London managers. Having declined an earlier offer from Covent Garden, he took an engagement there for five years at a weekly salary rising from £16 to £18, making his début as Orestes in The Distressed Mother on 16 September 1816.

Macready made a nervous start, a top-heavy auburn wig emphasizing his chubbiness. Leigh Hunt described him as ‘one of the plainest and most awkwardly made men that ever trod the stage. His voice is even coarser than his personage’ (Trewin, 44). Certainly the young Macready was not handsomely endowed physically, but other critics commended the power, harmony, and moderation of his voice, the expressiveness of his eyes, and the sharp intelligence of his characterization. Edmund Kean, conspicuous in a private box, joined in the warm applause, and the play was ‘given out’ for repetition the following Monday and Friday. Montevole in Robert Jephson's Julia, or, The Italian Lover on 30 September augmented his reputation, after which Macready was put to a sterner test, alternating Othello and Iago with Charles Mayne Young. His Othello (10 October) was creditable, but, in what was for him a new role, as Iago (15 October) he was judged to be tame—in Hazlitt's description ‘a mischievous boy’ whipping the ‘great humming-top’ which was Young's Othello. The quality of roles assigned to Macready by the Covent Garden manager, Henry Harris, who dubbed him the ‘Cock Grumbler’, was variable. He was deemed to be unsuited in appearance to romantic and heroic roles and was often cast as the villain in melodramas and more ambitious pieces. Macready confided his dissatisfaction to his diary, wondering whether to quit the stage and make a trial of his talents in some other profession. But, even in roles which he despised, he enhanced his reputation. On 15 April 1817, as Valentino, a traitor, in Dimond's Conquest of Taranto, he outshone Junius Brutus Booth, whose engagement at Covent Garden had deprived Macready of roles he might otherwise have expected to play. As Pescara in Sheil's The Apostate (3 May 1817), he won the praise of the German scholar Ludwig Tieck; he also met the great French actor Talma at the conclusion of John Philip Kemble's farewell season. Gradually better roles came his way—Romeo to Eliza O'Neill's Juliet, and Richard III (25 October 1819), in which he inevitably invited comparison with Edmund Kean. Colley Cibber's version was still preferred to Shakespeare and, as so often happened on big occasions, the first few scenes eluded Macready. He gained in confidence, and by Richard's death the actor's victory was complete.

Macready's success as Richard III restored the fortunes of Covent Garden, but when, following the death of George III, King Lear was restored to the repertory, Macready refused Harris's offer of the title role—in competition with Edmund Kean at Drury Lane—playing Edmund instead (13 April 1820), with Booth taking Lear. Macready's opportunity came with Sheridan Knowles's new play, Virginius. He took charge of rehearsals, the intensity of which was resented by senior actors unused to taking orders from anyone, let alone from the youngest member of the company. His careful preparation, as both actor and stage-manager, paid dividends: Virginius (17 May 1820) was a triumph and remained in his repertory to the end of his life. For his benefit (9 June 1820) Macready made his début as Macbeth, which was to become his favourite and most successful role. On tour in Scotland that summer he was supported by the fourteen-year-old Catherine Atkins, whom he induced his father to engage for the Bristol company of which he was then manager.

Back at Covent Garden for the 1820–21 season, Macready failed as Iachimo in Cymbeline (18 October 1820). In Richard III (12 March 1821) he partially reinstated Shakespeare's text, but in The Tempest (15 May 1821) he countenanced further maltreatment by Reynolds of the Davenant–Dryden perversion. In his London début as Hamlet he presented a lachrymose, self-pitying, inky cloaked Dane (8 June 1821), but scored a success as the King in 2 Henry IV, staged as a coronation attraction, a performance captured in John Jackson's portrait (now in the National Portrait Gallery). Having fulfilled his original five-year contract at Covent Garden, Macready renewed his engagement for a further five years, beginning in the autumn of 1821. The 1821–2 season was idle and inglorious for him, the only noteworthy event being a successful revival of Julius Caesar, in which he played Cassius. In spring 1822 Charles Kemble, by his brother John Philip's gift, became co-proprietor of Covent Garden. The already uneasy relationship between Macready and Charles Kemble deteriorated when Macready returned from a European vacation and found the Covent Garden regime much reduced by ill-advised economies. Many senior members of the company defected to Drury Lane, where R. W. Elliston trebled their salaries. Macready remained at Covent Garden, performing the title role in Mary Russell Mitford's Julian (15 March 1823) and adding Cardinal Wolsey and King John to his Shakespearian repertory. Increasingly dissatisfied, after a heated exchange of letters and pamphlets with the Covent Garden management, he terminated his contract and joined the other refugees at Drury Lane, at a salary of £20 a night.

Macready made his Drury Lane début in Virginius on 13 October 1823, followed by his London début as Leontes (3 November 1823) and another—inferior—piece by Sheridan Knowles, Caius Gracchus (18 November 1823). His only other new part was the Duke in Measure for Measure (1 May 1824). In the autumn of 1823, following her father's death by drowning, Catherine Atkins had become Macready's betrothed. Although Macready had attained thirty years of age, he postponed his marriage, at his sister Laetitia's suggestion, if not insistence, so that his bride-to-be could benefit from a period of study and improvement under her future sister-in-law's supervision. The wedding ceremony took place at St Pancras Church on 24 June 1824. Laetitia lived with the Macreadys throughout their married life, surviving her sister-in-law by six years.

Macready appeared at Drury Lane intermittently for thirteen years, during which he did not add materially to his reputation. His success as Remont in Sheil's expurgated adaptation of Massinger's The Fatal Dowry (5 January 1825) was interrupted by serious illness (inflammation of the diaphragm) which caused concern for his life. He recovered to play the title role in Knowles's William Tell (11 May 1825), which, though turgid and long-winded, provided him with some effectively overwrought scenes suited to his style. Following some provincial engagements, a period of rest in a country retreat near Denbigh, and a short season at Drury Lane (10 April to 19 May 1826) in which he undertook no new roles, Macready, with his wife and sister, sailed from Liverpool on 2 September 1826 for New York. He made his American début, under the management of Stephen Price, at the Park Theatre, New York, on 2 October 1826, as Virginius, and was warmly received by the public and the press. While in New York he attended a performance of Julius Caesar in which Mark Antony was played by a vigorous 21-year-old called Edwin Forrest, whom he met socially. By the time he took his farewell benefit in New York on 4 June 1827, playing Macbeth and Delaval, Macready had appeared in Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Albany, and other American cities, in all of which he had been enthusiastically received.

Back at Drury Lane—under Price's management—Macready appeared as Macbeth (12 November 1827), a performance which impressed the German visitor Prince Pückler-Muskau for its striking excellence in the murder scene, the banquet scene, and the last act. He could salvage little from either Reynolds's historical patchwork play Edward the Black Prince (28 January 1828) or Lord Porchester's Don Pedro (10 March 1828). On 7 April 1828 Macready appeared in Paris as Macbeth, partnered by Harriet Smithson, whose previous performances in that city had been greatly admired (particularly by Hugo, Dumas, and Berlioz), but her Lady Macbeth was exposed as tame, and feeble beside Macready's fiery and energetic Thane. Macready returned to Paris in June and July, adding to his laurels—he was judged the equal of Talma—as Virginius, Tell, Hamlet, and Othello.

After returning home, Macready devoted himself principally to starring engagements in the provinces. His father died on 11 April 1829 and for two years Macready, with Richard Brunton, held the lease of the Theatre Royal, Bristol, until his stepmother, Sarah Macready, took it over in her own right in 1833. Macready's first child, Christina Laetitia, was born on 26 December 1830; he was now in a financial position to support a family, his income in 1828 amounting to £2361 and in 1829 to £2265. On 18 October 1830 he appeared at Drury Lane for the first time in two years, and on 15 December he triumphed over the unpromising raw material of Lord Byron's play Werner to achieve a major success as the gloomy, conscience-stricken title character. In 1831–2 Macready's appearances amounted to only fifty-two, compared with ninety-nine in the previous season. The highlight of the 1832–3 season was Othello (26 November 1832), with Edmund Kean in the title role infuriating Macready (Iago) by resorting to the old trick of upstaging—standing a few paces further upstage than his interlocutor, who was consequently forced to appear in profile to the audience. Strained though their professional relationship had been, Macready was a pallbearer at Kean's funeral on 25 May 1833.

Even though Macready's recent achievements had not been outstanding, retirements and deaths combined to place him, at the age of forty, at the forefront of his profession. Unfortunately, the control of the two patent theatres (Covent Garden and Drury Lane), which had enjoyed a monopoly over legitimate drama in London since the restoration of Charles II, was now in the hands of one man, Alfred Bunn, whose character and habits were altogether antipathetic to Macready. Macready naturally resisted Bunn's attempt to reduce the large salaries which he considered to be the ruin of the stage. Furthermore, Bunn was determined not to let his principal tragedian rust in idleness, and exacted fifteen appearances from Macready between 5 and 30 October 1833. On 21 November Macready, struggling against illness, insufficient rehearsal, and deplorable mounting, played Antony in Antony and Cleopatra. Shortly afterwards he offered to pay Bunn a premium in exchange for release from his contract, but the manager declined. However, he did enjoy some remission in the number of his performances leading up to Bunn's much-heralded production of Byron's Sardanapalus on 10 April 1834. For his benefit on 23 April Macready made his metropolitan début as King Lear, having played the role in Swansea the previous year. Though purged of Tate's absurdities, this was still an incomplete text (without the Fool), but Macready had begun his assault on one of the peaks of the Shakespearian repertory, which, eventually, he was to conquer.

On 21 September 1835 Macready signed a contract with Bunn for Drury Lane (Covent Garden having passed out of Bunn's control). Although Macready had a veto over roles which he deemed to be of a melodramatic character, he was still subject to Bunn's will in the classical repertory. He could find no spark in Jaques (3 October), but off-stage, at the end of act III of Richard III on 29 April 1836, his anger was ignited by the sight of Bunn attending to his managerial duties. Macready denounced the manager as a ‘damned scoundrel’ and struck him in the face. Although he had been caught unaware, Bunn seemed to be getting the upper hand in the ensuing struggle before the two men were separated. Macready unburdened both his anger and his shame in his diary: ‘this most indiscreet most imprudent, most blameable action’ (Macready's Reminiscences, 380). The incident reverberated through the press. Bunn sued Macready for assault. The barrister and playwright Thomas Noon Talfourd appeared for Macready, and, though his attempt to present his client as the victim was unconvincing, the actor got off relatively lightly with damages of £150. The warm reception which greeted Macready when he appeared as Macbeth at Covent Garden on 11 May 1836 was indicative of public sympathy. Nevertheless, at the end of his performance he publicly expressed his self-reproach and regret for his intemperate and imprudent act.

Regrettable though the incident with Bunn undoubtedly was, it proved to be the turning of the tide in Macready's affairs which, taken at the flood, led on to fortune, for at Covent Garden he laid the foundations of what were to be the major achievements of his career. In Benjamin Thompson's The Stranger on 18 May 1836 he appeared for the first time with Helen Faucit, his future leading lady. On 26 May, after the first performance of Ion, by his erstwhile defending counsel Talfourd, he conversed at a celebratory supper with Wordsworth, Walter Savage Landor, Mary Russell Mitford, Clarkson Stanfield, John Forster, and Robert Browning, to whom he said: ‘Will you write me a tragedy, and save me going to America?’ (Archer, 99). The result, Browning's Strafford, was performed on 1 May 1837, before which, on 4 January, Macready and Helen Faucit had appeared in The Duchess de la Vallière, by another recruit to the theatre from the ranks of literature—Edward Bulwer (later Bulwer-Lytton). From the Shakespeare canon King John (6 October 1836), with Macready as the King and Helen Faucit as Constance, had emerged as a play worthy of further attention.

Macready now nerved himself to take the decisive step of entering into management, with the hazards of which he had been familiar since childhood. He did so at a peculiarly difficult time, for, though the recommendation of the 1832 select committee on the dramatic literature to abolish the patent theatres' monopoly had been defeated in parliament, its eventual implementation was not in doubt. In assuming the management of Covent Garden Macready was asserting not only his professional leadership, but also the status of the patent houses as national theatres devoted to higher ideals than commercial advantage. Charles Kean declined Macready's invitation to join the company, but Samuel Phelps, James Anderson, George Bennett, Mary Amelia Warner, Priscilla Horton (later Reed), and Helen Faucit accepted. The opening production was The Winter's Tale (30 September 1837), in which Macready made a slow start as Leontes, but he and his carefully rehearsed company brought the evening to a commanding conclusion. He gave reprises of his established roles—Hamlet, Virginius, and Macbeth—but his Henry V (14 November) had no gleam of the famous revival to come. Since he regarded a strong musical side as an integral part of a patent theatre's repertory, Macready staged John Pyke Hullah's new comic opera The Barbers of Bassora (11 November) and T. B. Rooke's new dramatic opera Amilie, or, The Love Test (2 December). No royalist, he eschewed the practice of raising seat prices for a royal command performance, and as a consequence the house for Queen Victoria's visit to Werner on 17 November was uncomfortably overcrowded. This, alas, was exceptional and as Christmas approached Macready was said to have lost £3000. The coffers were replenished by the pantomime Harlequin and Peeping Tom of Coventry, of which Clarkson Stanfield's diorama was the centrepiece, but Macready had not entered management to stage spectacle, pantomime, and opera, and on 25 January 1838 he staked his reputation on a revival of King Lear. Rehearsals had begun on 4 January; every aspect of the production received Macready's painstaking attention, none more so than the Fool, to whose overdue restoration he was committed. Initially he cast Drinkwater Meadows, but he seized on George Bartley's suggestion that a woman should play the part, and allotted it to Priscilla Horton. John Forster, who described the Fool as ‘interwoven with Lear’, hailed Macready's performance as ‘the only perfect picture we have had of Lear since the age of Betterton’ (The Examiner, 4 Feb 1838).

The encouragement of new dramatists was as central to Macready's enterprise as the restoration of the classical repertory. Since mid-November 1837 he had been discussing a new play with Edward Bulwer, and their surviving correspondence reveals the extent of the actor's contribution to the work. The Lady of Lyons opened on 15 February 1838, but the author's identity was not revealed until 24 February, by which time, after an uncertain start, the play's success was assured. Bulwer's refusal of royalties reflected the commitment of Macready's circle to his enterprise: Stanfield had accepted only half (£150) of the payment due to him for the pantomime diorama. The success of The Lady of Lyons (thirty-three performances) afforded Macready time and money to mount a large-scale production of Coriolanus (12 March 1838), in which the scenery and crowd effects eclipsed his own lacklustre performance as Caius Marcius. For his benefit on 7 April he staged Byron's The Two Foscari and on 23 May he introduced Sheridan Knowles's new play, Woman's Wit, or, Love's Disguises, which was enthusiastically received. During his first season as a manager Macready had devoted fifty-five of the 211 acting nights to performances of eleven Shakespeare plays. Had he not been opposed to the long-run system, he could have exploited the success of King Lear and Coriolanus further.

Macready maintained substantially the same company for his second Covent Garden season, which began on 24 September 1838 with Coriolanus, in which he ceded the title role to John Vandenhoff. The first great effort was The Tempest (13 October), but, although Macready banished Dryden and Davenant, he also dispensed with the dialogue of the first scene in favour of a spectacular shipwreck. Macready's partnership with Bulwer was resumed with Richelieu, on which the two men collaborated for several months prior to its successful première on 7 March 1839. Following a rapturous first night, at which Bulwer no longer hedged his bets under the cloak of anonymity, Richelieu ran for thirty-seven performances with Macready as Richelieu, Helen Faucit as his ward, Julie de Mortemar, and Samuel Phelps as Father Joseph. For Miss Faucit's benefit on 18 April As You Like It was staged, but Macready's major Shakespearian work of the season was Henry V (10 June). His own performance as Henry was merely conventional, but Clarkson Stanfield's pictorial illustrations of Chorus's speeches significantly advanced the art of scenic design to critical and popular acclaim, though Macready restricted performances to four a week. The excessive caution of his proposition to the Covent Garden proprietors for a third season suggests that he did not desire or intend it to be accepted. At a public dinner at the Freemasons' Tavern on 20 July 1839, with the duke of Sussex in the chair and Dickens, Bulwer, and Richard Monckton Milnes present, Macready proclaimed that his poverty, not his will, had obliged him to desist from management. His achievements were considerable: the restoration of Shakespeare's plays and their staging on a hitherto unexampled scale; the encouragement of new drama, Bulwer in particular; and, while ensuring that his own pre-eminence was not challenged, a high standard of ensemble acting—all of this within a policy dedicated to maintaining a repertory commensurate with a national theatre and opposed to the exploitation of long runs. At this time Macready sought the post of reader of plays in the lord chamberlain's office. His autocratic and irascible temperament made him ill-suited for such a function, but perhaps he thought it would afford him the opportunity to shape the nation's drama without incurring the financial risks of management. In the event, Charles Kemble was succeeded by his son John Mitchell Kemble.

For the next two and a half years Macready worked as an actor, principally at the Haymarket Theatre under Benjamin Webster. He appeared in two further works by Bulwer—The Sea Captain, or, The Birthright (31 October 1839) and Money (8 December 1840)—with the writing and staging of which he was closely involved. Bulwer's contemporary comedy of manners, Money, had been postponed because of the death of Macready's daughter Joan on 25 November 1840. Other personal matters intruded: it was during this period at the Haymarket that Macready was the subject of backstage gossip—by Ellen Tree, Mary Warner, and Harriette Lacy—concerning his relationship with Helen Faucit. The young actress's nightly visits to Macready's room after the performance were avowedly for help with her studies, but even Macready could not entirely discount his protégée's feelings for him or suppress completely his own susceptibility to what he described, in a poem inscribed in her album, as Miss Faucit's ‘holier charm’ (Trewin, 168).

The days of the patent theatres' monopoly were now clearly numbered, and Macready, who in his evidence to the 1832 select committee had advocated reform rather than abolition, was tempted to seize one last opportunity to manage one of the great metropolitan houses. On 4 October 1841, encouraged by Dickens, Forster, and the rest of his loyal coterie, Macready took Drury Lane, but the refurbishments required were such that the season did not open until 27 December. He regrouped many of his Covent Garden company with the additions of Miss Fortescue, Marston, Compton, Hudson, and the Keeleys. Following a careful revival of The Merchant of Venice (27 December 1841), albeit without either Morocco or Arragon, Macready retrieved The Two Gentlemen of Verona (29 December 1841), but it was with Acis and Galatea (5 February 1842), arranged and adapted from Handel with sets by Clarkson Stanfield, that he achieved his first great success. Other features of the season were Douglas Jerrold's new play The Prisoner of War (8 February)—no role for Macready, but the Keeleys in fine form—and Gerald Griffin's Gisippus, which sustained twenty performances with Macready in the title role and Helen Faucit as Sophronia.

Macready's second Drury Lane season opened on 1 October 1842, when his sombre Jaques took his place in an elaborately mounted (the Forest of Arden by courtesy of Clarkson Stanfield) and strongly cast As You Like It. This was followed on 24 October by a lavish production of King John with Macready at his best as the subtly sinister John, Helen Faucit a high-souled Constance, and Phelps exuding manly pathos as Hubert. William Telbin's scenery set the standard for Victorian pictorial revivals of Shakespeare's histories, and was complemented by historically accurate costumes, attributed by Charles Shattuck to Colonel Charles Hamilton Smith. The importance of the two revivals was both immediate and far-reaching, as Charles Shattuck indicates:

But taken as a whole—the arrangement of the text, the ensemble playing, the stage decoration, the stage management, and the overall conception—King John was, together with As You Like It which had opened the season three weeks earlier, the finest work that Macready had ever put together. (Shattuck, Macready's King John, 2)

Macready fared less well with new plays. Westland Marston's The Patrician's Daughter (10 December 1842), in which he played Mordaunt, proved a barren success, as did Browning's A Blot in the 'Scutcheon (11 February 1843), in which he did not appear. For his benefit on 24 February 1843 Macready, whose forte was not comedy, made the surprising choice of Much Ado about Nothing; his Benedick was described by James Anderson (Claudio) as being as melancholy as a mourning coach in a snowstorm. Unsparingly, the evening was concluded with Comus. By 6 May it was apparent that Macready could not come to satisfactory terms with the Drury Lane committee for the continuation of his management. He made his valedictory appearance on 4 June 1843 as Macbeth. At a dinner at Willis's Rooms on 19 June, the duke of Cambridge presented Macready with a testimonial in the form of a massive and elaborate piece of silver in which Shakespeare and the tragedian both featured prominently. In response Macready proclaimed, ‘I aimed at elevating everything represented on the stage’, and accepted ‘this crowning gift’ as an assurance that ‘whatever may have been the pecuniary results of my attempts to redeem the Drama, I have secured some portion of public confidence’ (Macready's Reminiscences, 527). At Drury Lane, Macready had abided by the same guiding principles—restoring Shakespeare, encouraging new plays, improving standards of acting, scenery, and soon—as he had at Covent Garden, and in doing so he had secured a greatly increased portion of public confidence, not only for himself, but also for the profession which he had so reluctantly joined and of which he was now the undisputed leader. But Macready had made little, if any, money as a manager, and it was to the accumulation of sufficient funds to ensure a dignified and comfortable retirement that he devoted the remaining years of his career.

On 5 September 1843 Macready sailed from Liverpool for America. Samuel Phelps, who under Macready's management had smarted from having his talents held in check, declined to accompany him, recognizing his own opportunity at home during Macready's absence. John Ryder went instead, to play seconds and help with the tour arrangements. In New York the English actors were visited by Edwin Forrest, whose marriage to Catherine Sinclair at St Paul's, Covent Garden, Macready had attended in June 1837. Macready opened at the Park Theatre with Macbeth on 25 September 1843 and proceeded to Philadelphia (where he met Charlotte Cushman), Boston, Baltimore, St Louis, New Orleans, and Montreal. He played an extensive repertory, his heavy Shakespearian parts being particularly well received. He was befriended by Emerson, Longfellow, and other men of eminence and returned home after a year's absence some £5500 the wealthier.

In December 1844, accompanied by his wife, Macready went to Paris to carry out engagements with Helen Faucit. Their performances in Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth, and Virginius were warmly received; Théophile Gautier, George Sand, Eugène Delacroix, Hugo, and Dumas all expressed their admiration. After returning to England early in 1845, Macready devoted the next three years principally to provincial engagements. In London he undertook a series of short engagements (usually for a stated number of weeks at three nights a week) at the Princess's Theatre in Oxford Street, under the management of J. M. Maddox. His repertory was predominantly Shakespearian, but on 20 May 1846 he created the role of James V of Scotland in The King of the Commons by the Revd James White of Bonchurch. On 22 November 1847 he appeared in his own botched arrangement of Sir Henry Taylor's Philip Van Artevelde. On 7 December 1847 Macready returned to Covent Garden to play the death scene of King Henry IV in a programme entitled ‘Shakespeare Night’ to raise funds for the purchase of Shakespeare's birthplace. Back at the Princess's in spring 1848 there was little rapport with his leading lady, Fanny Kemble. From 24 April to 8 May 1848 he appeared for Mary Warner at the Marylebone Theatre, and on 10 July he took a farewell benefit at Drury Lane, commanded by the queen, in which Charlotte Cushman played Queen Katharine to his Wolsey. Receipts totalled over £1100, the house being so crowded that some disturbance marred the occasion.

This disturbance presaged Macready's ill-fated farewell visit to America, on which he set forth from Liverpool on 9 September 1848, again accompanied by John Ryder. There were rumours of hostility towards Macready, but his first performance on 4 October (in New York as Macbeth) was warmly received. Unwisely, Macready made a curtain speech thanking his audience for having refuted his detractors. The speech was seized upon as a challenge by James Oakes, a friend of Edwin Forrest, who was generally perceived as the source of anti-Macready feeling. Oakes published a lengthy piece in the Boston Mail (30 October) setting out Forrest's grievances, foremost that Macready had treated the American actor with indignity during his 1845 visit to London and that Macready or John Forster had packed the Princess's Theatre with a hostile claque. During Macready's engagement (20 November to 2 December 1848) at the Arch Theatre in Philadelphia, Forrest appeared at the Walnut Theatre, duplicating Macready's role wherever possible. The two actors published rival accounts of what had taken place in 1845 and Macready began an action against Forrest. While awaiting documents from England, Macready continued his tour, visiting Baltimore, Washington, Richmond, New Orleans, and St Charles, without incident until, in Cincinnati, half a raw carcass of sheep was propelled onto the stage by a ruffian in the gallery. Even this was only a drunken gesture, and the audience rallied indignantly round the actor.

During the performance of Macbeth at the Astor Place Theatre, New York, on 7 May, the stage was rained with copper cents, eggs, apples, potatoes, and a bottle of horribly pungent asafoetida, which splashed Macready's costume. By the third act chairs were being thrown from the gallery and, though Macready stood his ground apparently unmoved, the performance was abandoned. Meanwhile, at the Broadway Theatre, Edwin Forrest had completed his performance—as Macbeth—uninterrupted. Macready's next appearance was announced for 10 May, when posses of police were stationed in the auditorium. Trouble-makers—fewer in number—who had infiltrated the auditorium were ejected by the police, but this further incited the mob outside, who bombarded the theatre with loose paving stones. Troops retaliated in self-preservation, and between seventeen and twenty rioters were killed and many others injured. Macready finished his performance, thanked his supporters, and then, having changed clothes with another actor, made his escape, accompanied only by Robert Emmett, initially by carriage to New Rochelle, then to Boston, and ten days later home to England. Macready had shown considerable courage, but he had also been characteristically tactless and self-assertive. He was, furthermore, the victim of a nationalist undercurrent sweeping America to which the unfavourable accounts of the country by Frances Trollope and Dickens had contributed. The Astor Place riot and the circumstances surrounding it were to be the subject of Richard Nelson's play Two Shakespearian Actors (1990).

Following his return to England, Macready undertook farewell performances in the provinces and in London. In two seasons at the Haymarket Theatre (8 October to 8 December 1849 and 28 October to 3 February 1851) he gave reprises of his Shakespearian repertory and his contemporary successes Richelieu and Virginius. On 1 February 1850 he performed at Windsor Castle in Julius Caesar, playing Brutus to the Antony of Charles Kean, whose appointment as director of the Windsor Theatricals he had deeply resented. The definitive farewell performance took place at Drury Lane on 26 February 1851, with Mary Warner (Lady Macbeth) and Phelps (Macduff) supporting Macready's valediction as Macbeth. The occasion reverberated with excitement and enthusiasm, but Macready remained dignified and in his curtain speech steadfastly avoided any show of simulated sorrow. The inevitable public dinner followed on 1 March, with Bulwer in the chair, speeches by Dickens, Thackeray, and Bunsen, and the recitation by Forster of Tennyson's sonnet ‘To W. C. Macready’:

Farewell, Macready, since this night we part,

Go, take thine honours home …

Thine is it that our drama did not die,

Nor flicker down to brainless pantomime,

And those gilt gauds men-children swarm to see.

Farewell, Macready, moral, grave, sublime …

Macready retired to a substantial house in Sherborne, Dorset. On 18 September 1852 his wife died unexpectedly while the couple were visiting Plymouth; many of their children went prematurely to the grave. In Sherborne, Macready busied himself with the abbey church, of which he became a church warden; the Sherborne Literary Institute, of which he was a board member; and an evening school, of which James Fraser, later bishop of Manchester, wrote as a member of the 1858 royal commission on popular education:

the only really efficient one [night school] that I witnessed at work, the only one full of life and progress and tone of the best kind, was the one at Sherborne which owes its origin and its prosperity to the philanthropic zeal and large sacrifices of money, time, and personal comfort of Mr Macready. (Report of the Assistant Commissioners Appointed to Inquire into the State of Popular Education in England, 1861, 2.52)

On 3 April 1860, at the age of sixty-seven, Macready married Cecile Louise Frederica Spencer (d. 1908), many years his junior, at Clifton parish church. Shortly afterwards the Macreadys moved to Wellington Square, Cheltenham. A son, Cecil Frederick Nevil Macready, was born on 7 May 1862; he pursued a military career, becoming a general and a baronet. For the last two years of his life Macready was an invalid—his hands were paralysed and his speech was blurred, though his mind remained active—and he died at 6 Wellington Square, Cheltenham, on 27 April 1873. He was buried in Kensal Green cemetery on 4 May. In 1914 Nevil Macready destroyed what would have been his father's richest legacy, his copious and uninhibited diaries, lest they might be injudiciously used. Sir Frederick Pollock's edition (2 vols., 1875; 1 vol., 1876) was highly selective, and though William Toynbee (1912) was more inclusive he omitted some important passages from the Pollock text. J. C. Trewin's abridged collection (1967) includes extracts from sixty-four manuscript pages discovered in 1960 and subsequently deposited in the Mander and Mitchenson Theatre Collection. Despite its incompleteness, Macready's diary constitutes a major resource, not only for the author's life and career, but also for the theatrical and cultural world of his day.

Macready was a complex individual. He had his father's quick temper, of which he was fully aware, although he was not always able to curb it in his professional dealings. His education at Rugby School encouraged his aspirations to the status of a gentleman, and while he resented being obliged to abandon his hopes of the church or the bar as a career, he equally resented any supposed slur upon his personal status or that of his enforced calling, the theatre. He cultivated his own learning and way of life in concert with his friendships with leading intellectual, literary, and artistic figures of his day (Carlyle, Tennyson, Dickens, Thackeray, Forster, Browning, and Bulwer), but, though this benefited the theatre, it also set Macready apart from the rest of his profession. His two periods of management were informed by high principles: he conducted his enterprises as national theatres, eschewing crude commercialism. He materially advanced the art of the theatre in all its facets: his rehearsals were unprecedented in their length and rigour; his attention to mise-en-scène set standards for generations to come; his acting versions marked a significant advance in the restoration of Shakespeare's texts; his encouragement of Browning, Bulwer, and Knowles resulted in plays of serious literary intent; and his engagement of actors of the calibre of Phelps, Ryder, and Helen Faucit produced a generally high standard of ensemble acting, even if Macready was sometimes swayed by jealousy of potential rivals. As an actor, although he was not endowed with great physical advantages, Macready had a good figure, a strong stage presence, an expressive face (especially his eyes), and a commanding voice, which, though not naturally musical, was capable of varied modulation. He avoided the excesses of the Kemble school of stately declamation, striving to introduce naturalistic familiarity, often through over-abrupt transitions from the declamatory to the conversational. He was also prone to insert the letter ‘a’ indiscriminately—thus Burnam Wood was seen ‘a-coming’. His greatest quality was his intellectual ability to penetrate and to express the psychological nature of his characters; thus Macbeth's moral decline was charted from the erect martial figure of act I to the self-abased murderer, with crouching form and stealthy felon-like step, at the end. Macready was ill-suited to comedy, but as a tragedian he scaled the Shakespearian peaks of Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth, and King Lear. In contemporary drama he succeeded in investing the works of Knowles, Bulwer, and others with a vitality and stageworthiness which compensated for, and even disguised, their deficiencies. For nigh on twenty years Macready dominated the English stage. Although he was a reluctant member of the acting profession, in it Macready achieved an eminence comparable to the leaders of the other professions to which he had aspired, and it was in large measure thanks to him that, by the end of the nineteenth century, the theatre enjoyed the status and esteem which had been denied it at the beginning.

Richard Foulkes DNB

John Jackson, (1778–1831), portrait painter and copyist, was born on 31 May 1778 at Lastingham in the North Riding of Yorkshire, the eldest son of John Jackson (1743–1822), tailor, and his wife, Ann Warrener (d. c.1837), who came from a Wesleyan missionary family. After a period at a private school at Nawton, some 15 miles away, Jackson worked in his father's tailoring business at Lastingham. In 1797 he left home to make his way as a miniature painter on ivory based at York and Whitby. The miniatures were ‘badly’ done but he ‘showed talent sketching likenesses on paper’ (Farington, Diary, 8.299) and by January 1800 he had been introduced, probably through a dissenting clergyman (most likely Whitby's Presbyterian minister, Thomas Watson) to Lord Mulgrave at Mulgrave Castle. Executed with the local house-painter's colours, his copy of Sir Joshua Reynolds's portrait of the playwright George Colman (pencil version dated 13 January 1800; BM) showed promise and, encouraged by his friends, the collectors the earl of Carlisle and Sir George Beaumont, Mulgrave allowed Jackson to stay frequently for more copying, Lord Carlisle also inviting him to Castle Howard for several months.

Jackson often accompanied the Mulgrave family to their Harley Street house in London and he worked in Beaumont's Grosvenor Square painting room imbibing Reynolds's teaching from his eloquent host. In July 1802 he moved on to stay with Lord Mulgrave's nephew by marriage, Viscount Dillon, at Ditchley near Oxford but failed to please Beaumont in particular with a copy of a Van Dyck portrait. Previously, in January, Beaumont had written complaining that Jackson should ‘abate his velocity & aim at correctness’ and subsequent letters to Mulgrave advised stiff reprimands. A year later he feared ‘a want of energy—of enthusiasm … the merest blockhead in the Academy can draw better than he can at present’ and advised that withdrawal of support might activate him (Owen and Brown, x, 156). In fact Jackson did achieve admission to the Royal Academy Schools in March 1805 and Mulgrave paid for a London studio in the Haymarket from the previous year. Finished just in time, Lady Mulgrave's portrait with her sister-in-law hung in the 1806 exhibition: typically the carefree painter had been discovered playing battledore and shuttlecock with his patron's aide-de-camp instead of quickly dispatching it. In 1807 or 1808 Jackson married Maria Fletcher (c.1780–1817), with whom he had a daughter who was born on 9 July 1808.

Unselfishly Jackson introduced a fellow student, David Wilkie, to his patrons and Mulgrave followed Beaumont in immediately commissioning him. Benjamin Haydon also benefited. Haydon describes Jackson at this time as ‘a good-natured looking man in black with his hair powdered whom I took as a clergyman’ (Haydon, 19). Mulgrave was first lord of the Admiralty from 1807 to 1810 and the trio of painters dined at the Admiralty frequently in their patrons' company. For all his fine eye for colour Jackson, whose watercolour portraits improved, was too often diverted, enjoying the salerooms and lectures and sketching in the country—in 1810 he tried to attract John Constable to the New Forest—and he shared little of his friends' limelight.

In 1813 Jackson began his task of producing portraits of eminent Methodists for the Wesleyan Methodist Magazine while Cadell and Davies employed him for the British Gallery of Contemporary Portraits, likenesses being created by a synthesis of existing images. He also pleased the anatomist Sir Charles Bell with his copy, costing more than an original work by Sir Henry Raeburn, of Reynolds's John Hunter. James Northcote used the likeable younger painter as an occasional model and became the first of a series of academicians depicted and exhibited by Jackson prior to his election as an associate of the Royal Academy in 1815 and Royal Academician in 1818.

Jackson remained greatly attached to Yorkshire and to the Mulgrave family in particular. In 1816 he painted a group portrait of his patron (in 1812 created earl of Mulgrave and Viscount Normanby), his brothers General the Hon. Edmund and the Hon. Augustus Phipps with Sir George Beaumont (oil sketch; priv. coll.) that was engraved by William Ward (1820). He also made a five-week tour of the Low Countries with the general, visiting galleries in Antwerp and Brussels, where they were joined by the duchess of Richmond for an inspection of the Waterloo battleground. Only a few pencil sketches survive (V&A). Jackson exhibited two Yorkshire landscapes at the British Institution but was more successful with subject pictures and in 1827 with A Negro's Head, of which several versions survive (priv. coll.). The artist was delighted when the president of the institution, the marquess of Stafford, bought his Little Moses in 1815 for 50 guineas.

Jackson's wife, Maria, died on 4 March 1817 leaving two children, and on 11 August 1818 he married Matilda Louise (c.1796–1873), the daughter of James Ward RA, who also had a studio in Newman Street, Soho, where Jackson had moved in 1807. Farington wrote to Sir Thomas Lawrence that two days after marriage his wife was found to be mentally unbalanced; previously ‘her singularity of manner’ he had attributed to ‘indifferent health and relaxed nerves’ (MS letter, RA, LAW/2/249). Jackson's ‘equanimity’ enabled him to cope, and, although Matilda's expectations had been heightened by earlier admiration from Lord Chesterfield's nephew, she became inculcated with the Methodist faith and a devoted wife. The family settled happily in Hampstead then, in 1824, at 16 Grove End Road, St John's Wood, their youngest surviving child, Mulgrave Phipps, later aspiring to art criticism. Jackson retained his studio and owned a carriage, an indulgence he could barely afford while his charges for a half-length portrait remained about 50 guineas, giving him an income seldom reaching £1500 a year.

In December 1818 Jackson, long regarded as an amiable but silent member of the Beaumont circle, was invited to the baronet's Leicestershire seat, Coleorton Hall, to paint a portrait of its architect, George Dance RA (Leicester Art Gallery), and he also copied the Reynolds portraits of his hosts, one pair going to Constable. In the following year Jackson travelled with two Yorkshiremen—Francis Chantrey, the sculptor, and a Mr Read from Norton—through Paris and Geneva to Rome, where their president, Sir Thomas Lawrence, took his two new academicians in his carriage to see the sights. Chantrey was critical of Jackson's apathy and general indifference to art but the painter astounded observers with the speed and skill with which he worked copying Titian's Sacred and Profane Love in four days and on his outstanding portrait Antonio Canova (Yale U. CBA). Canova rewarded him by overseeing the Englishman's election to the Accademia di San Luca, Rome.

Jackson, like Northcote, was imbued with the Reynolds tradition and he showed little originality in composition. He was now at the height of his powers, and at the Royal Academy dinner in 1827 Lawrence described Jackson's portrait John Flaxman, RA as ‘a grand achievement of the English School’ (Redgrave, Artists, 245) and his Lord Dover was also approved by the critics. As George Agar Ellis, Dover played a leading political role in persuading the government to establish the National Gallery and he and Beaumont sometimes discussed the matter in Jackson's studio. Dover owned both portraits as well as a fine one of his wife by Jackson, who did not often succeed with portraits of women. Jackson was generally considered rarely to reach Lawrence's heights, although his portrayals were ‘flesh and blood’ according to Haydon, who cared less for the president's fine work.

In 1820 Mulgrave suffered a ‘creeping palsy’ that incapacitated him. Like Beaumont, who died in 1827, Jackson became gloomier over his last decade. In London he was often seen with Beaumont, Wilkie, and the Phipps brothers, while the general still welcomed him to Mulgrave Castle. But Jackson's religion was paramount. Constable suspected that he did many good works: equally at ease in church or chapel, he gave £50 in 1826 to improve the church at Lastingham and a smaller copy of Correggio's Agony in the Garden as an altarpiece. He was at Lastingham again in August 1830, having been in poor health, to see his mother, and he told Northcote he was ready for work again, ‘now necessary for life’ (RA, AND/40/XXI). His final journey to Yorkshire to attend Mulgrave's funeral in 1831 proved too much for his weakened constitution and he died on 1 June at his home, 16 Grove End Road, St John's Wood, London.

Jackson's funeral and burial at Hinde Street Chapel, Marylebone, was attended mainly by Methodists. His family, left penniless, received £50 grants in 1831 and 1832 from the Royal Academy and his studio sale at Christies on 15 and 16 July 1831 yielded a disappointing £1032, although it included four works by Reynolds, his palette and Hogarth's; the former Jackson had used in youth and it was perhaps given him by Beaumont as a token of esteem. Fortunately he probably still owned his house and studio at his death; otherwise the Royal Academy would no doubt have continued its grants to his family, many of Jackson's friends being academicians who appreciated his virtues of kindness and generosity.

Felicity Owen DNB