The Hopetoun papers include the diary of Captain P.G.Carter of the Derbyshire Yeomanry who was a colleague of Billy Henderson's as ADC to the Viceroy. This diary includes a huge amount of information on Henderson's day to day life in India, There is an entry for 16 September 1941 which reads, 'Billy and I have decided it will be cheaper to employ the masseur, Ghulam, on a permanent basis -we're going to give him 50 rupees a month & he will be our servant and "live in".'

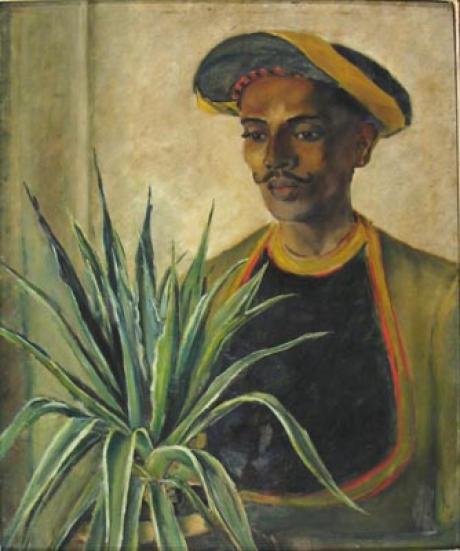

William "Billy" Henderson was ADC to Lord Wavell in India and also to Lord Linlithgow who proceeded him. Apparently Billy left all his diaries and photos (he was a keen photographer) to Lady Linlithgow (who became a great friend) and it is all on public display. His diaries would almost certainly have the name of the servent. William Henderson the 'companion' of the late Dr Frank Tait a professional psychiatrist who was given this portrait. William Henderson, painter: born near Frome, Somerset 25 September 1903; died Tisbury, Wiltshire 21 September 1993.

WILLIAM HENDERSON missed his 90th birthday by four days. The significance of that is not his age but the fact that his ear was as finely tuned, his hand as steady, his recall as complete, his eye as clear as they had ever been. He was a painter who spent most of his long life, with few distractions, looking, listening, capturing the essence of the fleeting moment.

He could take you back with him, a little boy going in a landau to Bath; out to tea with the Pitman family in 1914 - only not out to tea because they had heard he had a German boy to stay (son of Elizabeth von Arnim of Elizabeth and her German Garden) 'and of course you can't bring him'. 'In that case I don't come', and he didn't; to a Christmas party in the snow where the widow of Scott of the Antarctic brought her small son Peter naked but for a leopard skin; up the stairs and headlong into his friend Nicholas's study at Eton to be confronted by Queen Marie of Romania (Nicholas's mother) and Queen Mary, both apparently six feet tall and armed with parasols; third class from Venice to Vienna where Richard Strauss was conducting his The Legend of Joseph; to Cagnes, where he could reach out a hand through the window of Renoir's little wooden studio among the olive groves and touch the brushes which still lay within reach of the old man's wheelchair four years after his death.

He was a strange amalgam. A natural, gifted and, as the years went by, industrious artist who painted what he saw; fairly wealthy - not rich enough to be careless but too rich to need to earn a living and, by early conditioning and probably by temperament, a happily solitary man. Paris 1925: Oh] I do regret, yes I do, that I didn't go to a proper studio and apply myself more diligently. But it was difficult not to be entranced by Paris. I walked and walked and, once you start walking in Paris, you never want to stop. I rarely spoke to anyone.

Not quite true, I guess, if only because someone would always find an opportunity to speak to him; for he was one of the rare people whose friends were more numerous than his acquaintances. There were grand friends and beautiful ones and there was the missionary, the vicar's wife, his governess; there were not only Cecil Beaton, to whom he read daily after his stroke, but Beaton's secretary Eileen Hose, to whom, after Beaton's death, he was a great consolation. This particular gift of friendship may be why he evolved his own genre of painting which he called 'Conversation Pieces' - people in their settings, sometimes settings with their people. If he could have chosen his Master, it would have been Vuillard. But he remained his own master and, after two major exhibitions at the Redfern in the mid-Fifties, decided, since he had no need to chase the wheel of fashion, just to keep following his own hand and heart.

It all began unpropitiously with what he used to describe as 'aspects of a privileged childhood I could have done without': a stiff steam yacht with a yellow funnel in Poole Harbour; out with the guns aged five in a kilt; a bully and a hypocrite for a father who died when he was six (' 'Poor little boy, left without a father', they said. I thought they must be mad. How could one not want him dead?'), a Presbyterian mother who forbade him to visit Spain because of the Papists or to stay at No 1O with Margot Asquith because of the lovers; a moderately miserable prep school with a lot of cricket; Eton with one or two things that were not cricket; a desultory year at Magdalen and another in Paris, 'thinking I was studying art by walking across the Seine to a drawing lesson with a respectable lady near the Hotel d'Angleterre'.

But even she taught him something: 'metier', how to mix paints. Meticulous about his shirts and the objects of beauty that he cautiously gathered round him, about the touch of gouache with which he could miraculously conjure the sheen from a lustre dish, yet in the act of painting he was untidy: palette in a muddle, pages of sketch-books all over the floor, relaxed, disorganised, free - sure in his metier and his eye.

Two people turned the dilettante into a disciplined painter. The first was Judith Lear, widow of the vicar of Mells and niece of Sir John Millais, an elderly, bold and cultivated traveller. Returning from her annual visit to take the waters at Kreuzbad (1933), she joined Billy, more than 40 years her junior, at St Tropez. There on the quay, she sketching, he reading aloud from Heloise and Abelard (Helen Waddell), he looked over her shoulder. 'Judith, your perspectives are all wrong.' 'Then do it yourself' - and she made him. Back in England, he showed his sketches to Rom Landau, an itinerant Polish journalist who later died in some splendour in Marrakesh and who had studied drawing, sculpture and art criticism in Berlin. 'A certain talent. You'd better go to art school.' So, finally, Billy went - to the Westminster School of Art, with Mark Gertler and Eliot Hodgkin in residence.

Landau kept Billy drawing, drawing for four years which, for a man with Billy's blazing sense of colour, must have hurt. But afterwards he never stopped. Colour crept in, of course - sometimes from crayons, sometimes from caran d'ache with a little water applied. But before he painted a finished picture, oil or gouache, there would be books full of sketches. If it was wet, he drew through the windscreen; in bed, from the window, whenever the sun shone and the shadows fell. He came back from his last holiday in July with pages of weeping trees and swirling waters of the Dronne near Bordeilles and, when that was too cold, of the chimneypiece in his hotel room. A child once said to him: 'Oh] Billy, I wish I could paint like you.' 'Then' (quite formidably) 'start looking. Now. Look at everything until you really see it.' Writing to Judith Lear in 1941, the full panoply of a viceregal passage from Delhi into Kashmir (during the war he was ADC to Linlithgow and to Wavell, in the unlikely guise of a captain in the Marines):

From about 1.30, we went through the Punjab Plains. As you know, I adore plains and one saw real Indian life in all directions. Every tree that gave shade had some lovely group under it. The colours of the dresses and turbans of the men, like flowers against the dark shade and pale earth . . .

Sketching all the way and, in the margin, notes: 'lemon yellow, Indian red, raw umber, yellow ochre, cobalt blue . . .'.

So, in spite of the wonderful cars in which he stirred up the white dust of the pre-war roads of Europe and the waltzing through enchanted Bohemian castles, in spite of the parrot and a partiality for ormolu, Billy Henderson never belonged to society. He belonged to his dear friend of 35 years, Frank Tait, and to his painting. Above all, he was serene. He used to say of his rather clouded childhood: 'And yet I can't ever remember it raining.' For us, the same seems now to be true of his life.