John Larkins Cheese Richardson, the son of Robert Richardson and his wife, Mary Anne Romney, was born on 4 August 1810 in Bengal, India, and was baptised at Calcutta. His father, an East India Company civil servant, managed a raw silk factory at Kumarkhali. After education at the East India Company College at Addiscombe, near Croydon, in Surrey, England, Richardson joined the Bengal Horse Artillery in 1839. On 11 February 1834 at Agra he married Charlotte Laing, who, after bearing three children, died in 1842.

Richardson fought in the Afghanistan campaign of 1842. He distinguished himself in the storming of the hill fort of Istalif, being wounded and later decorated for gallantry. He was commissioned as captain in 1843, took part in the First Sikh War of 1845–46, and served as a staff officer until his retirement from the East India Company in 1851. While Richardson was serving in India, Henry Havelock, the hero of Lucknow, had recruited him to his band of evangelicals and he remained an evangelical all his life, as well as being a devoted Anglican.

In 1848 Richardson, whose lifelong passion for farming had been shown in 1842 with his subscription to The Farmer, began thinking of retirement to a farming life in one of the colonies. He took two years' sick leave in Cape Town, but, disliking South Africa, next considered New Zealand. In 1852, having retired to England, he sailed for New Zealand on the Slains Castle with his 10-year-old son for a preliminary view, leaving his daughters at school. He travelled extensively by foot, horse and canoe in the provinces of Wellington and Taranaki, and in Otago, where he decided to settle. Returning to England, in 1854 he published a witty and informative travel book, A summer's excursion in New Zealand,…by an Old Bengalee, and also a long, serious narrative poem, The first Christian martyr of the New Zealand church.

After three years in England acquiring necessary practical skills and collecting farm equipment, Richardson in 1856 sailed with his children in the Strathmore, bringing 20 tons of chattels. He bought 150 acres in South Otago by the Puerua River, built a thatched hut, and with his young son and one farm labourer set about clearing and fencing his farm, Willowmead. In 1858 he finished building a handsome two-storeyed homestead, which is still in use.

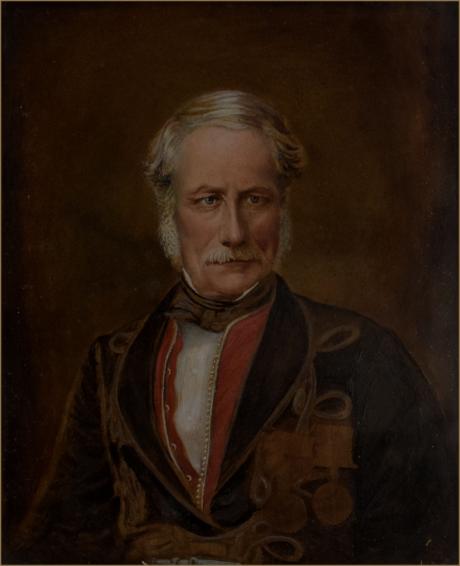

Richardson was aged 46 on his return to New Zealand, where he was known as Major Richardson. He was unhurried in manner and of cultivated speech; in appearance upright, thin and fair, with piercing blue eyes, alive with intelligence and humour. This humour was inseparable from his make-up. His entrance brought any gathering to life, and the pages of the Otago Witness were soon enlivened by his informative letters and articles on many topics, all spiced with his very individual brand of wit. Yet there was in his nature an underlying strain of pessimism, which later was no asset to him as a politician.

His soldiering background was always apparent, and as early as 1860 he began his successful efforts to found a series of volunteer rifle corps. This was connected, not with the wars in the North Island, but with a fear of aggression by Britain's enemies – France or America. In fact, he respected and sympathised with the Maori, who, he said, 'to this hour…have been treated as a thing of nought'. The Treaty of Waitangi, he said, was 'the veriest sham and delusion', 'a triumph of art over innocence.'

Richardson always claimed to prefer his Willowmead retreat to public life, yet his impetuous and emotional involvement in the issues of the day drew him into politics. The welfare of small farmers and the equitable distribution of land, linked to immigration, were his lasting obsessions: 'Land for the people, and people for the land'. As speaker in the Otago Provincial Council from April 1860 to May 1861, he was concerned in the dismissal of the superintendent, James Macandrew, in whose place he was elected in May 1861, on the eve of the discovery of gold in Otago. He coped energetically with the ensuing goldrush, using promptly the extra powers of administration granted him by the governor; but he disappointed Otago people by his over-cautious reluctance to embark on the large public works they felt the times demanded. His patrician manner irked them; they resented too his opposition to their favoured scheme of political separation from the northern provinces, to prevent Otago's new wealth from passing over its borders in taxes. Richardson's vision of New Zealand as a unified nation they saw as emotionalism. In the 1863 election for the superintendency they rejected him. They also repented of his election to the General Assembly, as he proceeded to use his formidable powers of rhetoric to frustrate their plan of separation.

In 1864, at the height of the wars in the North Island, Frederick Weld became premier with a policy of self-reliance: New Zealand was to assume responsibility for the war. Richardson's support for this led him to join Weld's cabinet as postmaster general. The extra taxation essential for self-reliance led to Weld's defeat in 1865, and Edward Stafford, by promising economy, was able to replace him. Richardson was deeply affected by the downfall of Weld, for whom his respect amounted almost to reverence. Refusing Stafford's invitation to join his ministry, he went home, embittered, and there found himself so unpopular over the taxation issue and his stand on separation that he did not try for re-election to his Clutha seat in 1866. He accepted instead an invitation to represent New Plymouth, whose interests he had often championed, and which he now represented until March 1867.

In 1866 Stafford had reconstructed his ministry, and Richardson, appointed to the Legislative Council in April 1867, now reluctantly agreed to join him, provided he should be without portfolio; although he did accept the unpopular duty of guiding government legislation through the Upper House. Otago found Stafford's fiscal programme even more damaging than Weld's. At the end of the session Richardson faced a jeering, hooting mob on the Dunedin wharf, and his progress up the street with police protection was preceded by a band playing 'The rogue's march'.

In 1867 as commissioner to examine the claims of the imperial government for war expenditure, Richardson made a strong case for the abandonment of these claims. While the colonial treasurer, William Fitzherbert, was in England successfully presenting Richardson's report, Richardson himself, during a critical six months, was acting colonial treasurer.

Richardson's fiercest opponents never questioned his integrity. However sharp their criticism of his stubbornness and wrong-headedness, they repeatedly admitted his lofty aims. As speaker of the Legislative Council from 1868 to 1878, he commanded great respect. In 10 years he was never known to make a hasty judgement, or utter a discourteous word. He did, however, offend the members by publicly disapproving of the existence of a nominated upper chamber. Richardson's position as speaker ended his participation in debates, but with undiminished fervour he still contributed leading articles to a variety of papers, and gave innumerable public lectures – always instructive, occasionally very funny, but often examples of Victorian wordiness at its most sentimental.

Richardson also took an active interest in social questions. In 1869 Otago formed its university council, with Richardson as vice chancellor. Sixteen months later he succeeded the Reverend Thomas Burns as chancellor, and when in 1871 the university opened its doors, Richardson gave the inaugural address. He several times urged women as well as men to enrol, having made provision that nothing might hinder them. To Richardson Otago owes the distinction of being the first university in Australasia to admit women to its classes. Together with Learmonth Dalrymple he was also responsible for Dunedin's opening the first public high school for girls in the southern hemisphere. He later ensured that girls could compete with boys for provincial council scholarships. His ardent commitment to the higher education of women remains one of his major contributions to New Zealand. In 1873 he collaborated with James Bradshaw to shorten the working hours of women in workshops.

In 1875 at the approach of the abolition of the provinces he abandoned centralism and joined Otago's hopeless fight for the political separation of the two islands. This completed his reinstatement in the affections of Otago people, whose favour he had never courted. Created KB in 1875, Richardson died at Dunedin on 6 December 1878. As 'The Old Major' he had become a greatly beloved figure, and his death was sincerely mourned – 'the gentlest, bravest, and most just of men'.

'The old Major', as he was known, soon became politically active, first being elected to the Otago Provincial Council serving as its Superintendent during the goldrush years, then becoming an MP and, in 1868, Speaker of the Legislative Council. He was the father of a family that included two bright daughters and it was largely his advocacy that ensured the University of Otago should open its doors to women – becoming the first university in the Southern Hemisphere to admit women to all its classes.

A witty, cultivated man much in demand as a public speaker, Richardson was progressive on Maori land issues and in the 1870s was commissioner enquiring into British and Māori accounts of the wars. Māori, he protested, 'to this day has been treated as a thing of naught'. Legislation and other measures that he promoted, including attempts to control the rabbit nuisance already threatening pastoral farming, revealed a far-seeing mind. Richardson was intelligent, warm and conscientious, and his death in 1878 evoked great public mourning.

Bibliography

McCaig, J. B. 'The life of Sir John L. C. Richardson'. MA thesis, Otago, 1949

Obit. Morning Herald. 7 Dec. 1878

Richardson papers. MS. Otago Early Settlers Museum

Trotter, O. John Larkins Cheese Richardson: 'the gentlest, bravest and most just of men'. Dunedin, 2010

by Bernard John Foster, M.A., Research Officer, Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington.

History of Otago, McLintock, A. H. (1949)

Bruce Herald, 10 Dec 1878 (Obit).

Co-creator

Bernard John Foster, M.A., Research Officer, Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington.

John Larkins Cheese Richardson: 'the Gentlest, Bravest and Most Just of Men' Biography by Olive Trotter. published in 2010

This is the definitive biography of a much-beloved and respected colonial activist who became one of New Zealand's founding fathers. Born in Bengal in 1810, but educated in England, John Larkins Cheese Richardson spent his early career in the military in India, achieving the rank of Major. Wounded and twice decorated, he served in the Afghanistan campaign in 1842 and was Aide-de-Camp to Sir Harry Smith throughout the Sikh Wars. On his retirement from the army in the1850s, he spent four months in New Zealand and subsequently decided to migrate there permanently, settling in Otago in 1856. 'The old Major,' as he was known, soon became politically active, first being elected to the Otago Provincial Council, serving as its Superintendent during the gold rush years of the 1860s, and eventually becoming a Member of Parliament and Speaker of the Legislative Council. Richardson was a champion of female education and it was largely his advocacy that ensured the University of Otago should open its doors to women, becoming the first university in the Southern Hemisphere to admit women to all its classes. A witty, cultivated man much in demand as a public speaker, Richardson was progressive on Maori land issues and, in the 1870s, was a commissioner enquiring into British and Maori accounts of wars. The Maori, he protested, "to this day has been treated as a thing of naught." Legislation and other measures that he promoted, including attempts to control the rabbit nuisance already threatening pastoral farming, revealed a far-seeing mind. Richardson was intelligent, warm, and conscientious, and his death in 1878 evoked great public mourning.

Irvine was born in Lerwick in Shetland in June 1805. He lost his father aged only ten, and realised that survival in the world would have to come from his own hard work. He had left Shetland by 1826, arriving at London via Edinburgh. He studied at the Royal Academy and was awarded a medal in 1828. Fellow students included William Etty and Daniel Maclise, who he was particularly friendly with. In 1834 he was elected an associate of the Royal Scottish Academy, and also exhibited in London in 1838, specialising in portraits. He emigrated to Australia to join his son, and in 1863 he moved to Dunedin in New Zealand. He remained there until his death, aged eighty-three.