inscribed on the reverse

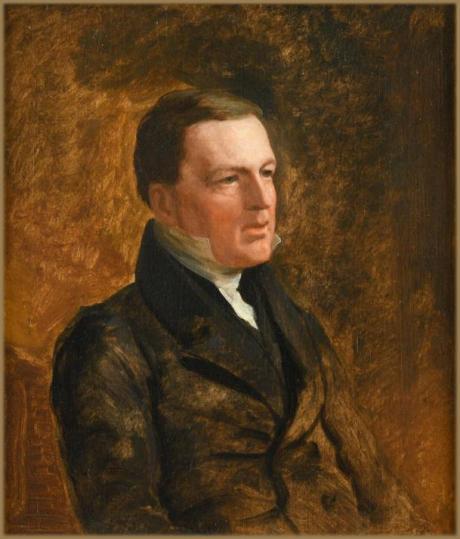

The present portrait is a study for Hayter's great painting 'The House of Commons', painted 1833-43, now in the National Portrait Gallery.

Charles Christopher Pepys, 1st Earl of Cottenham, PC, QC (/ˈpɛpɪs/; 29 April 1781 – 29 April 1851) was an English lawyer, judge and politician. He was twice Lord Chancellor of Great Britain.

Background and education

Cottenham was born on 29 April 1781 in Wimpole Street, Cavendish Square, London the second son of three sons of Sir William Pepys, 1st Baronet, a master in chancery, who was descended from John Pepys, of Cottenham, Cambridgeshire, a great-uncle of Samuel Pepys the diarist. Pepys was educated at Harrow School and at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he did not sit for the tripos but was content to graduate LLB in 1803. Contemporaries remembered him as a short,

stout, sturdy, thickset boy, of blunt speech and cold disposition, aiming at no distinction, making few friends … None could say that he was clever; some of his schoolfellows pronounced him dull. His dark, searching eyes, massive forehead and expressive lips, refuted the charge.

He never lost his 'air of independence and determination which indicated an inward consciousness of superiority' (Le Marchant, 59–60).

Pepys was called to the bar of Lincoln's Inn in 1804.

Legal and political career

Pepys was admitted a student of Lincoln's Inn on 26 January 1801 and was called to the bar on 23 November 1804, the same day as the future Viscount Melbourne. In 1837 he became treasurer of his inn. Like many of his distinguished contemporaries, he was a pupil of the famous special pleader, William Tidd. His fellow pupil, John Campbell, later Lord Campbell, described him as 'the greatest ornament of our [Tidd's] Bar' (Life of John, Lord Campbell, 1.138). He decided to practise at the emerging chancery bar (he was among the first generation of chancery lawyers who did not go circuit), so, having taken chambers in 16 Old Square, Lincoln's Inn, he began his study of equity with Sir Samuel Romilly. The fact that his father was a master in chancery must have helped his practice. Within five years of his call, his father wrote to Hannah More: 'The success of my second son at the Chancery Bar has been most rapid, and highly gratifying to me' (Gaussen, 2.295). His professional success came from his total dedication to his equity practice and his disdain for society; in later life his only recreation was foreign travel. A chancery advocate did not have to be an Erskine or a Scarlett. Pepys had a clear mind, reasoned cogently, was rarely repetitious, and 'never forgot that he was addressing a single judge and that judge a professional man' (Law Review, 14, 1853, 354).

Pepys's practice at the bar prospered, enabling him on 30 June 1821 to marry Caroline Elizabeth (1802–1868), the second daughter of William Wingfield KC, then chief justice of the Brecon circuit, and to become another master in chancery. On 24 August 1826 he received his silk gown from Lord Lyndhurst and became a bencher of his inn in November that year. Four years later he was appointed solicitor-general to Queen Adelaide, retaining that post until May 1832.

Whiggism was in Pepys's blood; his maternal grandfather had been the chancellor of the exchequer in the Rockingham administration in 1765. Though he had shown little political ambition, in July 1831 he entered the House of Commons as the member for Higham Ferrers, a seat which he exchanged the following September for Lord Fitzwilliam's borough of Malton. In the house he rarely spoke, and then on purely legal questions; his first speech, on 31 October 1831, was on the Bankruptcy Bill. The whigs had a paucity of lawyers in the house, and their predicament became acute when Sir William Horne, who had become attorney-general on Sir Thomas Denman'sappointment as lord chief justice in November 1832, proved to be a disastrous choice. In 1834 he was pushed out of office. Campbell succeeded him and, to the surprise of the profession, Pepys became solicitor-general on 22 February 1834, receiving the customary knighthood. As solicitor-general Pepys was not active in the house. He piloted the bill to establish the central criminal court and spoke in favour of the newPoor Law Bill. But he had no taste for debate and his most successful intervention was his speech moving the appointment of a select committee to inquire into the law of libel.

In September 1834 the master of the rolls, Sir John Leach, suddenly died. Campbell, to his mortification, was passed over in favour of Pepys who, at the instigation of Brougham (whom Pepys had impressed), became master of the rolls on 29 September and a privy councillor a few days later. Brougham wrote that Pepys's elevation 'was his own best title to the gratitude of the profession' (Brougham, 3.430).

The whigs returned to office in April 1835. The prime minister, Melbourne, resolved that Brougham should never again be his lord chancellor. The great seal was put into commission while the cabinet wrangled over an alternative to Brougham. The contest was between Henry Bickersteth and Pepys. On 17 January 1836 Pepys became lord chancellor of England, taking the title Baron Cottenham of Cottenham in the county of Cambridge. Greville described the promotion of this 'plain undistinguished man' as 'one of the most curious instances of elevation that ever occurred' (Greville Memoirs, 3.328). Pemberton Leigh, later Lord Kingsdown, recorded the comment that: 'Melbourne must have felt very much like a man who had parted with a brilliant capricious mistress and married his housekeeper' (Leigh, Recollections, 112; Edinburgh Review, 60). In 1841 the whigs were turned out of office. On their return in 1846 Cottenham became lord chancellor for the second time, again succeeding Lyndhurst.

Cottenham was unashamedly a party man, whose preference for whigs in his patronage appointments to the commissions of the peace and to the trusteeships of municipal charities infuriated the tories. But he failed his party in the Lords, as he had done in the Commons. A feeble debater, he was no match for Lyndhurst or Brougham. But Atlaythought that he 'was a much more useful member of the Cabinet than was generally suspected' (Atlay, 1.404), a judgement which Lord John Russell appeared to endorse, describing him as 'a direct man and a straightforward statesman' (Russell, 276).

A muted law reformer

On 28 April 1836 Cottenham introduced a bill for dividing and distributing the duties performed by the lord chancellor. The bill left the jurisdiction and procedure of the court of chancery untouched, although the equity business of the court of exchequerwas transferred to it. Its head was to be a permanent judge, the lord chief justice of the court of chancery, who was to devote himself solely to judicial business. The office of lord chancellor was to remain. Its holder would keep the great seal and its traditional patronage, and preside over the House of Lords and the hearing of appeals to the House of Lords and the privy council.

It was predictable that the bill would be opposed by Lyndhurst, who depicted Cottenham's chancellor as a lawyer without a court. More disconcerting was the opposition of Bickersteth, now Lord Langdale and Cottenham's successor as master of the rolls, who strongly disapproved of its main provisions. Cottenham's defence of the bill was, in Campbell's words, 'tame, confused, and dissuasive' (Life of John, Lord Campbell, 2.82). The bill was handsomely defeated and with its defeat died any further attempt by Cottenham radically to reform the court of chancery.

The fifty-one new orders in chancery in 1841, although making detailed reforms, were quite inadequate attempts to remedy the defects of equity procedure. Equally unsuccessful was Cottenham's attempt to implement the recommendations of the commission of inquiry into the bankruptcy and insolvency laws. But he did have some minor successes. For example, in 1838 he secured the enactment of a statute abolishing imprisonment for debt on mesne process; thereafter a person could not be arrested on the mere affidavit of another that he was owed £20. In 1841 the statute which had prohibited the clergy from all dealings in trade was repealed; the earlier statute had been interpreted to mean that if a clergyman was a shareholder in a joint-stock company, the company was an illegal association and could not recover moneys due to it. And an act of 1847 enabled trustees who wished to be relieved of the responsibility of administering the trust to pay trust money into court.

Cottenham as judge

Cottenham will not be remembered as a politician or as a law reformer. But as a judge he earned the praise, though not the love, of his contemporaries. Kingsdown said that he was 'one of the best judges I ever saw on the Bench' (Atlay, 1.402). Cottenham did not have Lyndhurst's brilliance of mind but his knowledge of equity was more profound. Among his decisions are Tulk <i>v.</i> Moxhay (1848), the corner-stone of the law of restrictive covenants, and Saunders <i>v.</i> Vautier (1841), which holds that all the beneficiaries of a trust, if of full age, may, if they so decide, determine the trust. The growth of the joint-stock company led to much litigation. Cottenham'sdecisions laid the foundations of modern company law. Prominent among them is Foss <i>v.</i> Harbottle (1843), which established that only the company, and not individual shareholders, can seek redress for the illegal acts of its directors.

Cottenham's judgments, which were meticulously prepared, are a model of what judgments should be. According to Le Marchant:

The style of them, like the character of the man, was perfectly free from all affectation and display; whether written or spoken, they were always simple, terse and perspicuous; clear and condensed in their summary of the facts, and in their exposition of law, comprehensive and vigorous, but at the same time, cautious and precise.

Le Marchant, 64

Cottenham, unlike Eldon, made up his mind quickly and once made it was a Herculean task to persuade him to change it. 'His demeanour in Court was not without a certain dignity, but its prominent feature was an austerity, amounting sometimes to harshness, which maintained his authority rather than conciliated esteem' (ibid., 64). Impatient of empty and repetitious rhetoric, he listened patiently to cogent argument, rarely interrupting 'except for the purpose of bringing it to an issue, by showing that he had detected its weak point' (ibid., 65). However, during his second chancellorship he became increasingly inaudible, irritable, and intolerant.

Cottenham's relationship with his judicial colleagues was an uneasy one. Langdale'sattack on his attempt to reform the court of chancery made a cool relationship even cooler. His dislike of the vice-chancellor, Sir James Knight Bruce, was long-standing. According to Lord Selborne, its source was their rivalry in Vice-Chancellor Shadwell'scourt, 'when that great lawyer, plain and dull of speech, had to endure what he regarded as daily affronts from his eloquent competitor' (Palmer, 1.375). Cottenhamwould not permit any deviation from the traditional practice of the court, even upholding one of the greater abuses of the master's office, ‘hourly warrants’, by which a fresh fee was payable every hour. In contrast, Knight Bruce was of a very different temper and had been allowed by an indulgent Lyndhurst to take procedural short cuts, freely granting amendments at the hearing of a cause. This practice infuriated Cottenham, who considered 'the system which he [had] to administer as the perfection of human wisdom' (Life of John, Lord Campbell, 2.207), and led to many bitter exchanges at the expense of hapless litigants. Knight Bruce was convinced that Cottenhamapproached his judgments with 'a disposition to reverse them' (Palmer, 1.375). Cottenham was on no better terms with the other vice-chancellor, Sir James Wigram.

To his contemporaries Cottenham was a man conscious of his dignity, touchy, aloof, self-centred. But he was a loving husband and devoted to his fifteen children, twelve of whom survived him. Unlike his father he had no interest in literature. His conversation with his few intimates, 'often enlivened by a vein of dry humour', was 'on the topics of the day' (Le Marchant, 67). Cottenham cared little for society. He was a private man.

Final years

During his second chancellorship, which began in 1846 and lasted almost four years, Cottenham's powers deteriorated. The burdens of office, combined with his conscientious devotion to his judicial duties, led to longer and longer delays in giving judgments, standing important cases over to the long vacation, and issuing ‘directions for enquiries’ to the masters for further investigation of the facts. The arrears of the court built up. In November 1847 Cottenham broke a blood-vessel in his throat, and was thought to be dying. But in the new year he was back in the house and in court, though seldom appearing in the cabinet. A personal attack by a disgruntled attorney, William Dimes, clouded his last years. Dimes had unsuccessfully brought suit against the Grand Junction Canal and had been committed by Cottenham for contempt for breach of an injunction. Dimes was a determined man and in 1849 brought an action to set aside Cottenham's judgment on the ground that Cottenham, a shareholder in the company, had an interest in the outcome of the proceedings. In June 1852 the House of Lords upheld that claim.

In the year following Dimes's action Cottenham was absent from court more frequently. On 27 May 1850 he abruptly resigned, to be granted in the following month the titles of Viscount Crowhurst and earl of Cottenham; in 1845 and 1849 he had succeeded to the baronetcies held by his older brother and uncle. He was advised to winter abroad and, in the spring of 1851, felt well enough to return home from Malta. But in Pietra Santa, near Lucca, in Italy, he was taken ill; he died on his seventieth birthday, 29 April 1851, and was buried in Totteridge in Hertfordshire.

His health, however, had been gradually failing and he resigned in 1850. Shortly before his retirement, he was created Viscount Crowhurst, of Crowhurst in the County of Surrey, and Earl of Cottenham, of Cottenham in the County of Cambridge. He lived at Prospect Place, Wimbledon from 1831 to 1851.

He had succeeded his elder brother as third Baronet in 1845. In 1849 he also succeeded a cousin as fourth Baronet of Juniper Hill.

Family

Lord Cottenham married Caroline Elizabeth, daughter of William Wingfield-Baker, in 1821. They had five sons and three daughters. He died at Pietra Santa, Lucca, in the Italian Grand Duchy of Tuscany, in April 1851, aged 70, and was succeeded by his eldest son, Charles. Lady Cottenham died in April 1868, aged 66. Cottenham's niece Emily Pepys (1833–1887), daughter of Henry Pepys, Bishop of Worcester, was a child diarist.

Sir George Hayter (17 December 1792 – 18 January 1871) was a notable English painter, specialising in portraits and large works involving in some cases several hundred individual portraits. Queen Victoria appreciated his merits and appointed Hayter her Principal Painter in Ordinary and also awarded him a Knighthood 1841.

Hayter was the son of Charles Hayter (1761–1835), a miniature painter and popular drawing-master and teacher of perspective who was appointed Professor of Perspective and Drawing to Princess Charlotte and published a well-known introduction to perspective and other works.

Initially tutored by his father, he went to the Royal Academy Schools early in 1808, but in the same year, after a disagreement about his art studies, ran away to sea as a Midshipman in the Royal Navy. His father secured his release, and they came to an agreement that Hayter should assist him while pursuing his own studies.

In 1809 he secretly married Sarah Milton, a lodger at his father's house (he was 15 or 16, she 28), the arrangement remaining secret until around 1811. Together they had three children Georgiana, Leopold and Henry.

At the Royal Academy Schools he studied under Fuseli, and in 1815 was appointed Painter of Miniatures and Portraits by Princess Charlotte. Hayter was awarded the British Institution’s premium for history painting for the Prophet Ezra (1815; Downton Castle), purchased by Richard Payne Knight.

Around 1816 his wife left him, for reasons which are not apparent. He subsequently began a relationship with Louisa Cauty, daughter of Sir William Cauty, with whom he lived openly for the next decade and who bore him two children, Angelo and Louisa (despite not having sought a divorce from his first wife).

Travel to Italy

Encouraged by his patron, John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, he travelled to Italy to study in 1816. There he met Canova, whose studio he attended while painting his portrait, where he absorbed Canova's classical style. He is also believed to have learned sculpture from Canova at this time. Canova was Perpetual Principal of the Accademia di San Luca (Rome's premier artistic institution) and doubtless put Hayter forward for honorary membership on the strength of his painting ‘The Tribute Money’ which was very favourably received in Rome. Hayter thereby became the Academy's youngest ever member.

Historical portraiture

Returning to London in 1818, Hayter practised as a portrait painter in oils and history painter. Dubbed ‘The Phoenix’ by William Beckford, Hayter showed a pomposity that irritated his fellow artists, but he mixed freely with many aristocratic families. His unconventional domestic life (separated from his wife, yet living with his mistress) set him apart from official Academy circles: he was never elected to the Royal Academy.

Hayter was most productive and innovative during the 1820s. George Agar-Ellis (later Lord Dover) commissioned the Trial of Queen Caroline in the House of Lords in 1820 (exh. Cauty's Great Rooms, 80-82 Pall Mall, 1823; London, National Portrait Gallery); painted on a large scale (2.33×2.66 m), Hayter's first (and most successful) contemporary history painting revealed a taste for high drama effectively realised. In the Trial of William, Lord Russell, in the Old Bailey in 1683 (1825; Woburn Abbey) Hayter celebrated John Russell's ancestry, in a work reminiscent of fashionable tableaux vivants of the country-house set.

Return to the Continent

In 1826 Hayter settled in Italy. The Banditti of Kurdistan Assisting Georgians in Carrying off Circassian Women (untraced), completed in Florence for John Proby, 1st Earl of Carysfort (exhibited British Institution 1829), demonstrated Hayter's assimilation of the style and exotic subject-matter of contemporary French Romantic art.

In 1827 his mistress, Louisa Cauty, died after poisoning herself with arsenic. Although it was apparently an accident, in a bid for attention, it was widely assumed that he had driven her to suicide, and he was forced by the scandal to move from Florence to Rome.

By late 1828 he was in Paris, where his portraits of English society members (some exhibited at the Salon in 1831) were stylistically akin to the work of recent French portrait painters such as François Gérard.

Royal patronage

In 1831 Hayter returned to England. His grandiose plan to paint the first sitting after the passage of the Reform Bill resulted in his painting Moving the Address to the Crown on the Opening of the First Reformed Parliament in the Old House of Commons, 5 February 1833 (1833–1843; London, N.P.G.), for which he executed nearly 400 portrait studies in oil. Hayter was an ardent supporter of the reform movement and this painting was not commissioned but to all intents and purposes a labour of love. It occupied him for ten years with no guarantee of financial reward. This is one of the last images executed of the interior of the old House of Commons before its destruction in the fire of 1834. The painting was finally purchased by the government for the nation in 1854, 20 years after it was started.

Having painted the young Princess Victoria (1832–3; destr.; oil sketch, Brit. Royal Col.), Hayter was not a surprising choice as the new Queen's 'Portrait and Historical Painter'. But on the death of Sir David Wilkie in 1841 Hayter's appointment as Principal Painter in Ordinary to the Queen caused some annoyance at the Royal Academy as this appointment had historically been the preserve of the President, then Sir Martin Archer Shee. In 1842 Hayter was knighted. He painted several royal ceremonies including Queen Victoria's coronation of 1838 and marriage of 1840 and also the Christening of the Prince of Wales of 1843 (all Brit. Royal Col.). He also painted several royal portraits including his most well-known work the State Portrait of the new Queen Victoria. Several versions of this portrait were done, with the assistance of the artist's son Angelo, to be sent as diplomatic gifts. Hayter's active period at court was short-lived, however, because Albert preferred German painters such as F. X. Winterhalter.

Several significant examples of Hayter's works from this period remain a part of the Royal Collection, and both the State Portrait and Wedding painting are among those displayed to the public at Buckingham Palace. There is also a full-scale version of the State Portrait in the National Portrait Gallery and smaller copy at Holyrood House.

Later years

By the mid-1840s Hayter's portrait style was considered old-fashioned. He adjusted his type of history painting to suit the more literal taste of the early Victorian era (e.g. Wellington Viewing Napoleon's Effigy at Madame Tussaud's; destr. 1925; engraving, 1854).

Hayter also painted several large religious paintings including two depicting important Reformist events, 'Bishop Latimer Preaching at Paul's Cross' and 'The Martyrdom of Bishops Ridley and Latimer' (exh. 1855), both of which were given to the Art Museum, Princeton University, USA in 1984. He painted several biblical scenes from the Old and New Testament, among them The Angels Ministering to Christ in 1849 (V&A) and Joseph Interpreting the Baker's Dream in 1854 (Lancaster City Museums). He also produced fluent landscape watercolours (many of Italian views), etchings (he published a volume in 1833), decorative designs and sculpture. The contents of Hayter's studio were auctioned at Christie's, London, on 19 April 1871.

His younger brother, John (1800–1895), was also an artist, known chiefly as a portrait draughtsman in chalks and crayons and his younger sister Anne worked as a miniaturist. Some sources say that the influential printmaker Stanley William Hayter was a direct descendant from John Hayter, although others say the ancestor was Sir George Hayter himself.[1] However the family tree of John and George Hayter published in Crisps Visitations shows no possible link to SW Hayter. What is known for certain is that the French painter and writer, Jean René Bazaine was a great great grandson of George Hayter, through his eldest daughter Georgiana Elizabeth, who married Pierre-Dominique Bazaine older brother of Marshal Bazaine.

References

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Barbara Coffey Bryant, "Hayter, Sir George (1792–1871)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 7 June 2007

- ^ Chilvers, I.; Osborne, H. (1988). The Oxford dictionary of art. Oxford University Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-19-860476-1. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ Henry, M. (2016). Politics Personified: Portraiture, caricature and visual culture in Britain, c.1830-80. Manchester University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-5261-1170-8. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ *Innovation in printmaking: Obituary of Mr S W Hayter, The Times, London, May 7, 1988

- ^ Visitation of England and Wales, Volume 17 1911, ed. Frederick Arthur Crisp, reprinted 1997 by Heritage Books Inc.

- ^ Jean Bazaine: Couleurs et Mots: le cherche midi éditeur, 1997 (entretiens avec Paul Ricœur et Henri Maldiney)

Further reading

- R. Ormond: Early Victorian Portraits, 2 vols, London N.P.G. cat. (London, 1973)

- Drawings by Sir George and John Hayter (exh. cat. by B. Coffey [Bryant], London, Morton Morris, 1982) [incl. checklist of prints]

- R. Walker: Regency Portraits, 2 vols, London N.P.G. cat. (London, 1986)

- O. Millar: The Victorian Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen, 2 vols (Cambridge, 1992)

- B. Bryant: Sir George Hayter's Drawings at Duncombe Park: Family Ties and a "Melancholy Event", Apollo, cxxxv (1992), pp. 240–50 [incl. newly pubd letter of 1827]

Gallery

-

The Trial of Queen Caroline in the House of Lords 1820 (188 portraits), completed 1823

-

The House of Commons sitting for the first time following the passing of the Reform Act 5 February 1833 (375 portraits)

-

Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool and Prime Minister, 1823 (for Trial of Queen Caroline picture)

-

General Thomas Graham, 1st Baron Lynedoch 1823

-

Duchess of Kent (mother of Queen Victoria), 1835

-

Antonio Canova painted in 1817

-

Queen Louise of Belgium, Windsor 1837

-

Edwin Landseer drawn in 1825

-

Lady Stuart de Rothesayand her daughters, Paris 1830

-

Lord Stuart de Rothesay, British Ambassador to France, Paris 1830

-

The Hon. Charlotte and The Hon. Louisa Stuart, daughters of Baron Stuart de Rothesay, Paris 1830

-

Saith Satoor and Ali Hassan Bey, 1831. Saith Satoor was the protégé of Prince Abbas Mirza, Crown Prince of Persia

-

Sofia Kiselyova, daughter of Count Stanislav Potocki 1831

-

The Hon. Mrs. Caroline Norton, society beauty and author, 1832

-

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey Prime Minister 1830–1834

-

Lord Melbourne Prime Minister 1834, 1835–1841

-

Lady Elizabeth Harcourt, eldest daughter of 2nd Earl of Lucan and wife of George Harcourt

-

John Montagu, 7th Earl of Sandwich (1811–1884), 7th Earl of Sandwich

-

John Spencer, 3rd Earl Spencer (1782–1845)

-

Lady Louisa Stuart at the age of ninety-three, sketch in oils

-

John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford (1766–1839)

-

John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford (1766–1839)

-

Admiral Sir Edward Codrington 1835

-

William Wilberforce(1759–1833)

-

The Duke of Wellington(1839), for the House of Commons picture

-

Rt Hon John Johnson, Lord Mayor of London1845

-

Hemsted Park, three studies with trees and storm clouds, 1856

91 paintings by or after George Hayter at the Art UK site