Hygieia Goddess of good health, cleanliness, and sanitation. In Greek mythology, Hygeia was the daughter and assistant of Aesculapius (sometimes spelled Asklepios), the God of Medicine and Healing. Hygeia's classical symbol was a bowl containing a medicinal potion with the serpent of Wisdom (or guardianship) partaking it. This is the same serpent of Wisdom, which appears on the caduceus, the staff of Aesculapius, which is the symbol of medicine. Hygieia as well as her four sisters each performed a facet of Apollo's art: Hygieia ("Hygiene" the goddess/personification of health, cleanliness, and sanitation); Panacea (the goddess of Universal remedy); Iaso (the goddess of recuperation from illness); Aceso (the goddess of the healing process); and Aglaïa (the goddess of beauty, splendor, glory, magnificence, and adornment). The Rod of Aesculapius, and a snake aswell as the Cockerel are all symbols which further allude to Aesculapius her father and her important role as his assistant . The cockerel or rooster was also sacred to the god and was the bird they sacrificed as his altar. The laurel wreath was a symbol of Apollo and the leaf itself was believed to have spiritual and physical cleansing abilities.

Hygieia also played an important part in her father's cult. While her father was more directly associated with healing, she was associated with the prevention of sickness and the continuation of good health. Her name is the source of the word "hygiene". Hygieia was imported by the Romans as the goddess Valetudo, the goddess of personal health, but in time she started to be increasingly identified with the ancient Italian goddess of social welfare, Salus. At Athens, Hygieia was the subject of a local cult since at least the 7th century BC.[citation needed] "Athena Hygieia" was one of the cult titles given to Athena, as Plutarch recounts of the building of the Parthenon (447-432 BC):

A strange accident happened in the course of building, which showed that the goddess was not averse to the work, but was aiding and co-operating to bring it to perfection. One of the artificers, the quickest and the handiest workman among them all, with a slip of his foot fell down from a great height, and lay in a miserable condition, the physicians having no hope of his recovery. When Pericles was in distress about this, the goddess [Athena] appeared to him at night in a dream, and ordered a course of treatment, which he applied, and in a short time and with great ease cured the man. And upon this occasion it was that he set up a brass statue of Athena Hygieia, in the citadel near the altar, which they say was there before. But it was Phidias who wrought the goddess's image in gold, and he has his name inscribed on the pedestal as the workman of it. However, the cult of Hygieia as an independent goddess did not begin to spread out until the Delphic oracle recognized her, and after the devastating Plague of Athens (430-427 BC) and in Rome in 293 BC. In the 2nd century AD, Pausanias noted the statues both of Hygieia and of Athena Hygieia near the entrance to the Acropolis of Athens.

Hygieia's primary temples were in Epidaurus, Corinth, Cos and Pergamon. Pausanias remarked that, at the Asclepieion of Titane in Sicyon (founded by Alexanor, Asclepius' grandson), statues of Hygieia were covered by women's hair and pieces of Babylonian clothes. According to inscriptions, the same sacrifices were offered at Paros.

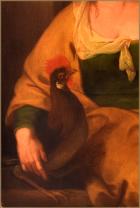

Ariphron, a Sicyonian artist from the 4th century BC wrote a well-known hymn celebrating her. Statues of Hygieia were created by Scopas, Bryaxis and Timotheus, among others, but there is no clear description of what they looked like. She was often depicted as a young woman feeding a large snake that was wrapped around her body or drinking from a jar that she carried. These attributes were later adopted by the Gallo-Roman healing goddess, Sirona. Hygieia was accompanied by her brother, Telesphorus.

While alchemists used secret symbols to disguise their chemical formulations, pharmacists used the tools of their trade – medical ingredients, pestle and mortar, and carboys (pharmaceutical vessels) – to advertise on shop signs and in trade publications. And though their origins may be forgotten, many of the visual markers are still used in drug packaging, in pharmacies and on medical buildings. Slithering their way through the iconography of pharmaceutical history, snakes appear, often wrapped around a staff, wherever you find apothecaries. Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine, carried a rod with a single snake, which became a medical symbol from the fifth century BCE.

The messenger of the gods, Hermes (the Roman god Mercury), acquired an extra snake on his staff, known as a caduceus. It’s perhaps not a coincidence, then, that the element mercury was a major chemical agent in the history of medicine and alchemy. For example, the evaporated vapour of mercury combined with snake venom was injected through the centre of the scalp as an antidote to snake bite and epilepsy. Both Hermes, the god of commerce, and Mercury, the god of trade, are a good fit for retail pharmacy.

The symmetrical proportions of the caduceus lend themselves to design. It was first used as a printer’s mark (colophon) by a 15th-century book publisher, and its association with medicine was revived in the early 19th century when a medical publisher adopted it. In France, snakes might also be found entwined around palm trees on 19th-century pharmaceutical labels. Perhaps this is a reminder of the exotic origins of many drugs? The Bowl of Hygeia is another mythological symbol associated with medicine. As the daughter and assistant of Asclepius, Hygeia tended to her father’s temples with a bowl of medicinal potion from which the serpent of wisdom drank, according to ancient Greek mythology.

The crocodile or alligator was associated with alchemy, and then with apothecary and chemist shops, though the reason for this association is unclear. It may simply have been a way of showing that the chemist had access to the rarest and most exotic ingredients, or, as nature writer Hannah Velten suggests, it may have been the reptiles’ similarity to another mythical creature, the wyvern, a sort of dragon. In the coat of arms of the Society of Apothecaries, the god Apollo stands over a two-legged wyvern, which represents disease.

Nowadays pharmacies display the green cross outside their shops. The green cross was first introduced as a pharmaceutical sign in continental Europe in the early 20th century as a replacement for the red cross, which was adopted by the International Red Cross in 1863. The green cross was not used in Britain until 1984, when the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain chose it as the standard symbol for pharmacy. The society stipulated that it should be produced in a specified shade of green, or in black and white, and that the word ‘pharmacy’ or ‘pharmacist’ should appear with it.

Another animal symbol commonly seen in pharmaceutical branding is the unicorn. It was first mentioned by the ancient Greeks as a symbol of purity and grace, whose spiralling horn had the power to heal, especially as an antidote to poisons. Often narwhal horns would wash up on beaches and be mistaken for the mystical unicorn’s horn and, like other animal horns and bones, be ground up for medical use. Along with the lion, the unicorn is the symbol of the British monarchy, and it was King James I who granted the Society of Apothecaries their charter in 1617 and their coat of arms with the two unicorns.

Angelica Catharina Kauffman, (1741–1807), history and portrait painter, was born on 30 October 1741 in Chur, Graubünden, Switzerland, the only child of Johann Joseph Kauffmann (1707–1782), an Austrian painter from the region of Bregenz, and his second wife, Cleofea Luz, or Lucin (1717–1757), a native of Chur. She was baptized in the Roman Catholic faith on 6 November 1741 as Anna Maria Angelica Catharina Kauffmann. In her early years she signed her name Maria Angelica Kauffman, though later she shortened it to Angelica Kauffman.

In 1742 Johann Joseph moved his family to Italy, first to Morbegno in Lombardy and ten years later to Como. As a girl Angelicademonstrated precocious talent for drawing and painting, so her father instructed her in these arts. She made rapid progress, and at the age of eleven produced a pastel portrait of the bishop of Como. In 1754 they travelled to Milan where she portrayed the archbishop, the duke and duchess of Modena, and Count Firmian, among others. After her mother's death in 1757, Kauffman returned with her father to Schwarzenberg, his native village, where the bishop of Constance commissioned Johann Joseph to paint frescoes in the parish church. Angelica assisted him and produced her first frescoes, half-length figures of thirteen apostles copied from a set of engravings after Giambattista Piazzetta. Early descriptions of Kauffman's youth note her musical talent and fine singing voice. In her thirteenth year she portrayed herself (1753; Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck) holding a sheet of music. Kauffman's first biographer, her brother-in-law Giuseppe Carlo Zucchi, recorded a memorable anecdote regarding her artistic abilities, a story repeated by De Rossi and all subsequent biographers. According to Zucchi's account, Kauffman was equally talented in music and art, yet she chose to forgo a chance of a promising musical career to pursue the profession of painting. She made this difficult choice, against the wishes of her friends, with the help of a priest who advised her that a career in painting would be more rewarding and less fleeting than music. This tale of Kauffman's wise judgement—a rather fanciful version based on truth—has become part of her almost legendary place in history as an unusually successful woman artist. Kauffman herself helped to create this image when she commemorated her youthful choice many years later in 1791—about the time Zucchi was preparing his biography—in a large allegorical self-portrait known in two versions (1791; Pushkin Museum, Moscow; 1794; Nostell Priory, Yorkshire). She portrayed herself hesitating between female personifications of Music, who implores her to stay, and Painting, who points prophetically up the rocky path to the Temple of Glory. Having made this choice, in 1759 Kauffman and her father returned to Italy so she could further develop her artistic skills, especially in perspective and proportion. They visited royal collections and other important galleries where Kauffman was granted permission to study and copy paintings in Milan, Modena, Venice, Piacenza, Parma, Bologna, Florence, Rome, and Naples. In 1762 she met the American painter Benjamin West in Florence, and the following year in Rome she became acquainted with the German antiquarian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, whose portrait she painted (1764; Kunsthaus, Zürich). She also befriended the British neo-classical painters Gavin Hamilton and Nathaniel Dance. These contacts influenced her aspiration to create history paintings of classical, mythological, and historical subjects, a rare ambition for a female artist, since very few women could receive training in this most demanding and highly regarded branch of the art. Among her early history paintings in Rome were Bacchus Finding the Abandoned Ariadne (1763; Rathaus, Bregenz) and Penelope at her Loom (1764; Hove Museum and Art Gallery, Sussex). Kauffman produced her earliest etchings, and she painted portraits in Naples of several English travellers. These included the actor David Garrick (1764; exh. Society of Artists, 1765; Burghley House, Northamptonshire) and Brownlow Cecil, Ninth Earl of Exeter (1764), who became an important patron. Her sketchbook (MS c.1762–5; V&A) contains portrait drawings, figure studies, and sketches of antique statuary. She learned anatomy by studying classical statues and nude drawings by other artists, for women were prohibited from the common practice of working directly from living models. As a female prodigy who was fluent in English and French as well as Italian and German, Kauffman attracted much attention. She was honoured with memberships in the Accademia del Disegno in Florence (1762), the Accademia Clementina in Bologna (1762), the Accademia di San Luca in Rome (1765), and later the Accademia delle Belle Arti in Venice (1781).

England and the Royal Academy of Arts, 1766–1781

Kauffman was especially popular with the English residents and grand tourists in Italy, so she readily accepted the invitation of Lady Wentworth to pursue her career in England. With plans for her father to follow later, the two women travelled via Paris to London, arriving on 22 June 1766. Within a week Kauffman visited Joshua Reynolds in his studio, and the two artists became friends. They made portraits of one another, and Reynolds, an advocate for history painting in England, became instrumental in promoting her career. He encouraged his boyhood friend John Parker, first Lord Boringdon, whom Kauffman had already painted in Naples, to purchase more of her pictures, most notably her portrait of Reynolds (1767) and several classical history paintings which include The Interview of Hector and Andromache (exh. RA, 1769) and Venus Showing Aeneas and Achates the Way to Carthage (exh. RA, 1769). These pictures and others are still at Saltram House, Devon, now in the collection of the National Trust.

Kauffman developed a reputation as a fashionable painter and was in great demand for portraits and subject pictures. She made a life-size portrait of the king's sister, The Duchess of Brunswick (1767, Royal Collection), whose mother, the dowager princess of Wales, visited Kauffman's studio. After lodging in London with a surgeon in Suffolk Street, Charing Cross, Kauffman took a house in Golden Square. Her father joined her in the summer of 1767 accompanied by his sister's daughter, Rosa Florini, who came to live with them until she married the architect Joseph Bonomi ARA, in 1775. In 1768 Kauffman was one of thirty-six founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts, one of only two women (the other was Mary Moser) [see Founders of the Royal Academy of Arts]. From 1769 to 1782 she sent a variety of pictures each year to the annual Royal Academy exhibitions and after she left England more sporadically until 1797. Her pictures ranged from portraits and allegories to mythology, history, and literary subjects from a variety of authors including Homer, Tasso, Spenser, Shakespeare, Metastasio, Alexander Pope, and Laurence Sterne. She tended to favour sentimental themes, but she was among the first in London to exhibit classical subjects, such as Cleopatra Adorning the Tomb of Mark Anthony (exh. RA, 1770; Burghley House), and the first artist to send British history subjects to the Royal Academy exhibitions. Examples of these are Vortigern, King of Britain Enamoured of Rowena at the Banquet of Hengist(exh. RA, 1770; Saltram House, Devon), Tender Eleanora Sucking the Venom out of the Wound of Edward I (exh. RA, 1776; priv. coll.), and Lady Elizabeth Grey Imploring of Edward IV, the Restitution of her Deceased Husband's Lands (exh. RA, 1776).

In 1773 Kauffman was one of five artists selected to paint the interior of St Paul's Cathedral in London, a project that was never carried out, and in 1774 she was in the group invited to decorate the Great Room of the Society of Arts, another abandoned scheme. In 1775 the Irish painter Nathaniel Hone tried to exhibit a satirical painting called The Conjuror (1775; National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin), intended to mock Reynolds. It offended Kauffman because of a nude female figure in the background thought to represent her. She complained to the academy, and as a result the picture was removed and Hone painted over the offending figure. Kauffman made four oval ceiling paintings for the council chamber of the academy's new premises at Somerset House in 1780. As part of an extensive didactic programme, they represent the four parts of painting as allegorical figures: Invention, Composition, Drawing (Design), and Colouring (1779–80; Royal Academy, London).

Portraiture, prints, and decorative arts

Portraits continued to provide a large part of Kauffman's income. In 1771 George, first Marquess Townshend, the lord lieutenant of Ireland, invited Kauffman to visit Dublin to paint his family (1771–2; priv. coll.). She remained in Ireland for six months and received many more commissions, including the portrait of Henry Loftus, the Earl of Ely, with his Wife and Two Nieces (1771; National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin). In the mid-1770s Kauffman painted several informal portraits of ladies dressed in pseudo-Turkish attire, such as Mary, Third Duchess of Richmond (exh. RA, 1775; Goodwood House, Sussex). Kauffman also collaborated with printmakers, especially Francesco Bartolozzi, William Wynne Ryland, Thomas Burke, and John Boydell, in the production of stipple engravings and mezzotints after her paintings. She was directly involved in the production and marketing of her prints, and was one of the few contemporary artists whose works were used to make 'mechanical paintings'—a relatively inexpensive process of colour reproduction invented in the 1770s that was especially suited for incorporation into decorative schemes. Matthew Boulton, an inventor and manufacturer, reproduced several of Kauffman's classical pictures through this process, in which an aquatint printed on coated paper was transferred onto canvas and then touched up by hand to create the appearance of an original painting. Kauffman'sstyle has been much associated with the decorative arts, in particular the neo-classical interior designs of Robert Adam. However, though many eighteenth-century walls, ceilings, porcelains, and furniture are ornamented with Kauffman's compositions, the vast majority were actually copied or reproduced by others after her pictures or simply based on her style. Kauffman may have provided some sketches for Adam, but she was not directly responsible for the many decorative works attributed to her. Nevertheless, the suitability of her neo-classical figures for such decoration ensured her continuing popularity, and her graceful style has made a permanent mark on the decorative arts, especially in England and Austria.

Marriage

Kauffman worked steadily and profitably, but she also enjoyed an active social life. Her alleged flirtations and relationships have been the subject of much speculation. She was an attractive though not beautiful woman, described as modest, intelligent, and charming. Contemporary references note her engagement to marry Nathaniel Dance in Rome in 1765. Gossip suggested she jilted Dance after she arrived in England in hope of marrying the more prominent artist Joshua Reynolds, but there is scant evidence to support this rumour. Her only documented relationship was a brief, disastrous marriage in 1767 to an impostor and bigamist, the so-called Count Frederick de Horn (or von Horn). This unfortunate and rather mysterious episode in her life was related at length in De Rossi's biography and has been corroborated by more recently discovered documents. Kauffman was deceived by this handsome man who claimed to be a wealthy Swedish nobleman. He persuaded her to marry him in secret without her father's consent, but then the scoundrel confronted her father with demands for money and threats of violence. Finally he was exposed as a fraud, arrested, signed a separation agreement (10 February 1768), and was released after promising to leave England forever. The parish register of St James's Church, Piccadilly, London, confirms a marriage on 20 November 1767 between Angelica Kauffman and Frederick de Horn, and according to Helbok there is evidence of a prior clandestine Roman Catholic ceremony in the San Jacopo Chapel of the Austrian embassy in London on 13 February 1767. It is noteworthy that despite the scandal and her personal distress, Kauffman never stopped working, her patrons and friends remained loyal, and her career prospered. She stayed single until 14 July 1781 when, after receiving a papal annulment (1778) and news of de Horn's death (1780), she married the Venetian painter Antonio Pietro Zucchi (1726–1795), who had long resided in England. A contract ensured Kauffman's continued control of her considerable wealth—over £14,000 by the time she left England—and she retained her own name.

Rome, 1782–1807

Five days after the marriage the couple and her father, whose health was failing, departed from England for the continent. They visited Schwarzenberg, Austria, and spent the winter in Venice, where her father died in January 1782. Kauffman and Zucchisettled in Rome in a large house on the via Sistina near the church of Santa Trinità dei Monti. Except for several sojourns in Naples, where she produced paintings for King Ferdinand I and Queen Carolina and taught the princesses to draw, Kauffman lived in Rome for the remainder of her life as a celebrated and well respected member of the international arts community. Zucchi took care of business matters and kept a list of her commissions (Memorie delle pitture, 1782–95, MS, London, RA) and a record of their accounts (BL, MS Egerton 2169). After his death on 26 December 1795 her cousin Johann Kauffmann came to live with her and run the household. She continued to send pictures to England, especially for George Bowles, an enthusiastic patron who eventually owned over fifty of her works, which included Pliny the Younger, with his Mother at the Eruption of Vesuvius (exh. RA, 1786; Princeton Art Museum, New Jersey), Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi, Pointing to her Children as her Treasures (exh. RA, 1786; Virginia Museum, Richmond), and Self-Portrait in the Character of Design Embraced by Poetry (1782; Iveagh Bequest, Kenwood House, London). She presented another self-portrait to the prestigious Medici collection of artists' portraits (1787; Uffizi Gallery, Florence). Kauffman's studio was a popular stop for fashionable visitors on the grand tour. Her clients and guests who came to enjoy conversation and music included artists, writers, aristocrats, and dealers from England, Germany, Austria, Russia, Sweden, and Poland. She developed friendships with international luminaries such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, with whom she corresponded after his departure from Italy in 1788, Antonio Canova, and Sir William Hamilton. Kauffman's long list of noble patrons included Catherine of Russia, Joseph II of Austria, Ludwig I of Bavaria, Prince Poniatowski, and King Stanislaus of Poland. Until the end of her life she painted both portraits and history paintings, including some religious subjects such as Christ and the Woman of Samaria (1796; Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich) and The Madonna Crowned by the Holy Trinity for the high altar of the church in Schwarzenberg (1802). During the French invasion of Rome in 1798 she never stopped working, although her health and fortune suffered. In 1802 Kauffman visited Florence, Milan, Como, and Venice for the last time. She died in Rome after an illness on 5 November 1807. Her elaborate funeral, arranged by Canova, was attended by members of the Accademia di San Luca and other foreign academies. She was buried on 7 November in the church of Sant' Andrea delle Fratte, Rome, beside her husband. Joseph Bonomireceived a letter from Rome (7 November 1807) that described Kauffman's final illness, death, and the funeral. On 23 December 1807 Benjamin West read Bonomi's translation of the letter to the general assembly of the Royal Academy, and a copy of this letter was entered into the academy records. A manuscript inventory of her possessions (25 January 1808; Getty Research Institute, Santa Monica) documents her wealth and fine taste, and her will (17 June 1803) is a testament to both her industriousness and her generosity. Kauffman's surviving paintings and prints confirm her reputation as one of the most accomplished, productive, resourceful, and influential women in the eighteenth century.

- Wendy Wassyng Roworth DNB