Russell, Charles Arthur, Baron Russell of Killowen (1832–1900), judge, was born on 10 November 1832 at Newry, co. Down, Ireland, the eldest son of Arthur Russell (1785–1845) and his wife, Margaret, daughter of Matthew Mullin and widow of John Hamill, a merchant of Belfast. After his father's death in 1845 Russell, along with his siblings, was brought up by his mother and their paternal uncle, Dr Charles William Russell, then a professor at and afterwards president of St Patrick's College, Maynooth. The Russells were a recusant family and the children were brought up in the Catholic faith. Russell attended a diocesan seminary in Belfast as his first school, was then taught at a private school in Newry, for two years, and finally spent one year at St Vincent's College, Castleknock, co. Dublin. He seems to have worked reasonably hard at school, but was not particularly distinguished. Although he later matriculated at Trinity College, Dublin (1856), he never graduated.

In January 1849 Russell began his legal training under Cornelius Denvir, a solicitor at Newry. After Denvir's death in 1852, his articles were transferred to Alexander O'Rorke of Belfast. Russell was admitted a solicitor in January 1854 and took charge of an office of O'Rorke's in Londonderry for six months. He then returned to Belfast, and practised in the county courts of Down and Antrim. Around that time extreme protestant sentiment had led to riots and other civil disturbances. When the resulting case came before the magistrates, Russell spoke well and defended the Catholics who had been involved in the violence. His speeches were reported in the provincial newspaper and public opinion swung strongly in his favour. His success on this occasion, along with the encouragement and recommendation of those among whom he practised, confirmed his resolve to become a barrister in London.

On 6 November 1856 Russell entered at Lincoln's Inn and moved permanently to London. In 1857 he became a pupil of Henry Bagshawe, then an equity junior with a large practice at the chancery bar. Remembered at this time as being grave, reserved, and hard-working, he acquired a considerable knowledge of real property law, but conveyancing and equity drafting did not interest him, and he left to join the common-law bar. He never attended the chambers of a pleader as the common-law procedure acts had largely removed the need for such specialization. He found time to write for newspapers and magazines, and contributed a weekly letter on current politics to the Dublin Nation. Though unsuccessful as a candidate for the inns of court studentship in 1858, he was awarded a certificate of honour. On 10 August 1858 he married Ellen (1836–1918), eldest daughter of Joseph Stevenson Mulholland MD of Belfast. In the Hilary term of 1859 he again competed for the studentship, which was awarded to Montague Cookson, afterwards Crackanthorpe KC.

On 26 January 1859 Russell was called to the bar and joined the northern circuit. He practised in the passage court, Liverpool, and within four years of being called to the bar was making £1000 per annum. He soon began to be known in London, and argued a case before Lord Westbury with such ability that he was offered a county court judgeship. He was knighted on 8 March 1866.

Judge and MP

In 1872 Russell took silk at the same time as Farrer, afterwards Baron Herschell, with whom he effectively divided all of the business cases on the circuit. In commercial cases, where rights mainly depended on written evidence, Russell's knowledge of business and of the law enabled him to go straight to the point and get through a long list quickly. However, where there was a conflict of evidence, his style of advocacy was open to criticism and complaint. He was not thought to be a pleasant antagonist. Despite a quick temper and a tendency to allow matters to become personal between himself and opposing counsel he was popular on circuit and said to treat witnesses fairly. With experience his methods became less aggressive; and it is said that he always had a helping hand for his juniors. His particular strengths were best displayed when fraud, perfidy, or malice were to be exposed. An aggressive cross-examiner, he was well able to deal with the dishonest witness. He also carried great sway when addressing a jury, not so much through oratorical brilliance as his exercise of a compelling moral authority. He was thorough in his preparation for difficult cases and expected high standards of his juniors and instructing solicitors, although he was sometimes faulted for impetuosity, in consultation as well as in court.

In 1875 Russell was invited to stand for the parliamentary seat of Durham but withdrew his candidacy once it became clear that his Catholicism might cause difficulties, suggesting instead that Farrer Herschell should take his place as the Liberal candidate. In 1876, on the death of Percival A. Pickering QC, he applied with other leaders of the circuit for the vacant judgeship of the court of passage at Liverpool but all lost out to Mr T. Henry Baylis QC. In 1880, after two further unsuccessful attempts, he was eventually returned to parliament, as an independent Liberal, for Dundalk, co. Louth, being opposed by home-rulers and Parnellites. He had been warned that he might be in physical danger if he stood, and one attempt at assault was indeed made, but his obvious courage and strength in self-defence deterred any further acts of violence.

Irish nationalism

When Russell entered parliament Irish nationalism was represented in the House of Commons by only a small minority of the Irish members. It was not until the franchise was expanded by the act of 1884, and as many as eighty-five members returned from Ireland to support the demand for an Irish parliament, that he pledged himself, together with the majority of Liberals, to the policy of home rule. Russell was nevertheless always a firm supporter of the Irish cause, and well before Gladstone and Parnell made their alliance frequently spoke in debates on Ireland and usually voted with the nationalists. In February 1881 he opposed W. E. Forster's Coercion Bill which involved the imprisonment of many men of good repute and was badly applied. Russell's opposition to the bill and the fact that many respectable men were imprisoned because of the bill meant that in Ireland the title ‘ex suspect’ became one of distinction. In March 1882 Russell opposed the proposal for an inquiry into the working of the Land Act, and in the following April he supported the government in the change of policy which led to the release of Forster's prisoners. He was outspoken against the measure of coercion which followed the Phoenix Park murders, renewing the hostility between the government and the Irish MPs, and sought by various amendments to mitigate the severity of the government proposals. In 1883 he delivered a long speech in the debate on the address, complaining that the legitimate demands for the redress of Irish grievances were disregarded; and in 1884 he spoke in support of an inquiry into the Maamtrasna trials. He seldom spoke in debates other than those connected with Ireland, but in 1883 he spoke in favour of a bill for creating a court of criminal appeal, contending that the interference of the home secretary with the sentences of judges was unconstitutional; and he also supported the granting of state aid to voluntary schools.

In 1882 Russell was offered a judgeship, which he was tempted to accept since he had no hope of retaining an Irish seat. He declined the offer, however, and decided to look for an English constituency. In 1885 he was returned for South Hackney, and was appointed attorney-general in Gladstone's government of 1886. His re-election upon taking office was opposed by the Conservatives, but he was again returned. He then threw himself into the home rule struggle with energy and determination. The alliance between Liberals and Parnellites enabled him to give full play to his enthusiasm, and he travelled all over England addressing public meetings, great and small, in every part of the country. His speeches in the House of Commons on the Home Rule Bill were probably his best parliamentary performances. In supporting the second reading he referred to 'the so-called loyal minority' as not being an aid but a hindrance to any solid union between England and Ireland, since he saw their loyalty as being strongly based on their self-interest. At the general election of 1886 he was again returned for South Hackney, defeating his opponent, C. J. Darling (afterwards a judge of the High Court), by a small majority. In 1887 he resisted the passing of the Coercion Bill of that year in a powerful speech.

In 1888 the Parnell Commission Act was passed. Its declared object was to create a tribunal to inquire into charges and allegations made against certain members of parliament and other persons by the defendants in the recent O'Donnell <i>v.</i> Walter case. Three of the judges were appointed commissioners, and the sittings began on 22 October. Russell appeared as leading counsel for Parnell, and the attorney-general, Sir R. Webster (afterwards Lord Alverstone and lord chief justice), was on the other side. The cross-examination of many of the Irish witnesses called by the attorney-general devolved upon Russell, and was successfully conducted in very difficult circumstances. He had no notice of the order in which they would appear, and had little information about them. Yet it was said that few witnesses left the box without being successfully attacked and disparaged. His famous speech for the defence occupied six days, and was concluded on 12 April 1889. It was well suited to the occasion and to the tribunal, and was undoubtedly his greatest forensic effort, although reputedly lacking in oratorical flourish.

Later years

In 1889 Russell involved himself in a criminal case and defended Mrs Florence Maybrick on the charge of poisoning her husband. The controversial case aroused a great deal of interest; Russell failed to prevent Maybrick's conviction, but her sentence was commuted from death to penal servitude. In 1890 he spoke in the debate in the House of Commons on the report of the special commission, his speech being described half-humorously in The Times as a blend of argument, invective, cajolery, and eloquent appeals to prejudice or sentiment so skilful that it added up to a very able speech.

On Gladstone's return to power in 1892 Russell was again appointed attorney-general, and was once more returned for Hackney by a large majority. In 1893, together with Sir R. Webster, he represented Great Britain in the Bering Sea arbitration. The case concerned the denial by Great Britain of the United States' exclusive jurisdiction over the sealing industry in the Bering Sea. Independently of this title (allegedly ‘purchased’ from Russia in 1867), the United States claimed jurisdiction as lawful protectors of seals bred in the disputed area on the basis of 'principles of right', or rules on which civilized nations ought to be agreed. This was stated to be international law. Russell and Webster contended that international law consisted of the rules which civilized nations had agreed to treat as binding. These rules were not to be ascertained by reference to 'principles of right', as counsel for the United States had argued, but were to be found in the records of international transactions. It was argued that, apart from actual consent, so ascertained, there was no universal moral standard; Russell and Webster won on this point. The discussion as to the future regulations for the management of the sealing industry occupied eight days. Russell's services were recognized by the award of the grand cross of St Michael and St George.

On 7 May 1894 Russell succeeded Charles Synge Christopher, Lord Bowen, as lord of appeal, and was raised to the peerage for life by the title of Russell of Killowen. In June of the same year, on the death of John Duke, Lord Coleridge, he was appointed lord chief justice. As chief justice he was reputed to be patient, courteous, and dignified. His extensive knowledge of the law was admired widely. No judge won the confidence and goodwill of the public more quickly or fully.

Russell took an interest in legal matters outside his immediate judicial duties. In 1895 he supported the judges of his division in the endeavour to establish the court for the trial of commercial causes, a project which for many years had been met by the strenuous and successful opposition of Lord Coleridge. In the same year he delivered an address in Lincoln's Inn hall on legal education. He dwelt at length on the failure of the existing system, and insisted that no student should be admitted to the degree of barrister who had not given proof of his professional competency. He bestowed faint praise on the Council of Legal Education, and urged that there should be a charter of a school of law with a senate not wholly composed of benchers and lawyers. His comments were resented and entirely disregarded.

In 1896, after gaining the conviction of the Jameson raiders and firmly laying down the law with clarity and force, Russell visited the United States for the purpose of delivering to American lawyers assembled at Saratoga in New York state an address entitled Arbitration: its Origin, History, and Prospects. In it he adhered to the view which he had laid before the Bering Sea arbitrators that international law was neither more nor less than what civilized nations have agreed shall be binding on one another. Amid great applause he expressed hopes for the peaceful settlement of disputes between nations.

In 1899, on the death of Farrer, Lord Herschell, Russell was appointed in his place to act as one of the arbitrators to determine the boundaries of British Guiana and Venezuela under the treaty of 2 February 1897. The arbitration was held in Paris, Great Britain being represented by Sir R. Webster and Sir R. Reid, and Venezuela by American counsel. Although Russell took little part in the discussion, he directed attention to the points at issue. The unanimous verdict was in favour of an award for Great Britain.

Death and assessment

In July 1900 Russell left London for the north Wales circuit. At Chester he suffered an attack of illness and was advised to go home. In a few days it became clear that something serious was wrong. After an attempt to save him through an operation, he died on 10 August at his home, 2 Cromwell Houses, Kensington. He was buried at Epsom, Surrey, on 14 August. He was survived by his wife and five sons, including Sir Charles Russell and Francis Xavier Joseph Russell, and four daughters.

Russell's keen intellect and resolute will helped him to unite much respect and even enthusiasm. Despite his often cold and forbidding manner, there was great kindliness in him as seen in his consideration for others. No reader, he was an indefatigable player of whist and piquet. He was also a familiar figure on racecourses, and was both interested in and knowledgeable about bloodstock. Russell was a large-minded man and his intimate friends included those who differed widely from him and each other in social class and position, politics, and religion.

When hard at work Russell shut himself up at his chambers at 3 Brick Court, Temple, or at his country house, Tadworth Court, near Epsom, but when free he was fond of socializing. He readily accepted invitations to address public meetings on politics, education, or for charitable projects. Even after he became chief justice he was ready to preside over public occasions, and especially at charity dinners. While he never failed to interest his audience his style was sombre, and, although well informed, he was inclined to dwell more on perceived shortcomings than to emphasize achievements.

Russell had a strong view of his obligation to enforce the duty of honesty and good faith in commercial transactions. His protests from the bench against fraud in the promotion of companies and the practice of receiving commissions were offered courageously, and he believed that good results would follow. The Secret Commissions Bill which he introduced in the House of Lords in 1900 required of him much effort, the collection of the necessary materials involving him in a personal correspondence with public bodies and individuals all over the kingdom.

Among his published works were New Views of Ireland, or, Irish Land: Grievances, Remedies, reprinted from the Daily Telegraph (1880); The Christian Schools of England and Recent Legislation Concerning them (1883); Address on Legal Education (1895); and Arbitration: its Origin, History, and Prospects: an Address to the Saratoga Congress, (1896).

Russell earned a great deal of money at the bar. His fee book shows that from 1862 to 1872 he made as junior on an average £3000 a year. In the ten years after he took silk in 1872 he made approximately £10,000 per annum; from 1882 to 1892 his annual earnings averaged nearly £16,000, and from 1893, when he was again appointed attorney-general, until he became a lord of appeal in April 1894, he received £32,826.

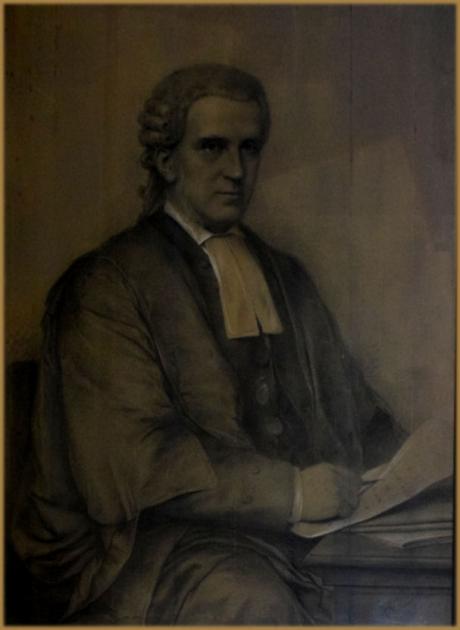

Russell was granted an honorary LLD by Trinity College, Dublin, in 1894, by Laval University, Canada, in 1896, and by Edinburgh University and the University of Cambridge in 1897. Lord Russell is remembered as a great judge and a man of personal integrity. The best likeness of him is the portrait by J. S. Sargent RA, now in the possession of his family, a replica of which is housed in the National Portrait Gallery.

J. C. Mathew, revised by Sinéad Agnew Oxford DNB

In the 1880s François Verheyden was one of an international group of artists who worked for Vanity Fair magazine. They produced caricatures of many of the leading characters of the day, including artists, athletes, royalty, statesmen, scientists, authors, actors, soldiers and scholars. There is a watercolour, published in Vanity Fair 5 May 1883 in the National Portrait Gallery Collection

NPG 2740. He was a Sculptor and made drawings and paintings, as well as a caricaturist. He was born in Belgium, remained a Belgian subject but lived in London from about 1870 and died in Wandsworth in 1919.