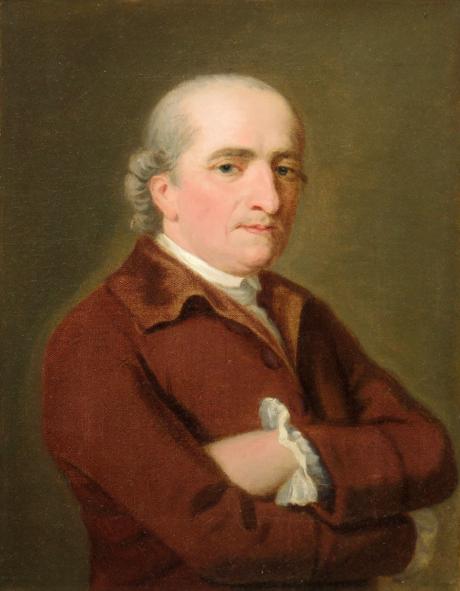

on the frame " WILLm SANDEMAN ESQ / By All.....R..MSAY La....t."

Private Collection New York, USA

William Sandeman (1722 in Luncarty, Scotland – 1790 in Perth, Scotland) was a leading Perthshire linen and later cotton manufacturer. For instance in 1782 alone, Perthshire produced 1.7 million yards of linen worth £81,000. Linen manufacture became by the 1760s a major Scottish industry, second only to agriculture. He was one of the pillars of the Scottish enlightenment.

William was born in 1722 in Luncarty just north of Perth, Scotland the fifth child of David Sandeman and his second wife Margaret Ramsay. David Sandeman was a merchant and magistrate (1735–63) of Perth .William with his first wife Christina Fleming had two children. With his second wife Mary Anderson he had a further 14 children (five of whom married five of the 20 children of Hector Turnbull, his bleachfield's business partner). In 1740, Robert and William Sandeman started a weaving business together, though Robert's expanding church duties in Dundee and Edinburgh removed him from the family business.William was exposed to the Glasite faith after the Perth meeting house first opened in 1733. He was later elected an elder of the Perth congregation for several years. In this position, he was expected to lead the congregation in both the worship and community service. As part of his Glasite obligations, he journeyed with his brother Robert in the first attempt to form a London Sandemanian congregation in 1761. When Robert extracted himself from the family business, William found another willing partner in Hector Turnbull. He was buried in the Greyfriars graveyard Perth with the inscription "William Sandeman manufacturer Perth and bleacher at Luncarty".

He manufactured linen in Perth and nearby Luncarty, for instance with an order of 12,000 to 15,000 yards of "Soldiers' shirting". In 1752 he leveled 12 acres (49,000 m2) of bleachfields in Luncarty. By 1790 when William died, the Luncarty bleachfields covered 80 acres (320,000 m2) and processed 500,000 yards of cloth annually. Second only to agriculture, linen manufacture was a major Scottish industry in the late 18th century — linen then became less important with the introduction of cotton.From an initial 12 acres, the works expanded, for nearly 250 years to occupy around 130 acres. In the 19th century the Luncarty Bleachfield works was the largest linen bleachfield in Scotland, supporting fine linen manufacture from the central belt of the country. Approximately 500,000 square yards of linen was bleached and finished at the works every year.

The bleaching at Luncarty was done by laying linen cloth out on grass in a Bleachfield in the sun. Chemical bleaching may have been introduced after the commercialisation of chlorine bleaches in the late 1800sThe bleaching at Luncarty was done by laying linen cloth out on grass in a Bleachfield in the sun. Chemical bleaching may have been introduced after the commercialisation of chlorine bleaches in the late 1800s.

In the early 1760s, William Sandeman opened two further linen centres: Milntown (now Milton) in Easter Ross and Fortrose on the Black Isle near Inverness. By 1765, these had almost 1000 spinners.

By the 1780s, cotton was replacing linen. In November 1784, Sandeman visited Lancashire cotton mills and Richard Arkwright the inventor who had pioneered cotton-spinning machinery in Derbyshire. Sandeman, Arkwright and others established the Tay River–powered cotton mill in Stanley (just north of Luncarty, Perthshire) in 1786/7 with 3200 spindles. The mill was originally water-powered but was later converted to steam and finally to electric power. For most of its history it produced cotton thread, but in the 20th century changed to cigarette ribbon. The Dempster & Co company was established in 1787 by seven men including Richard Arkwright, George Dempster and William Sandeman to build the mill on land feued from the Duke of Atholl to provide employment to Highlanders affected by the clearances.

Ramsay, Allan, of Kinkell (1713–1784), portrait painter, was born in Edinburgh, in the parish of New Kirk, on 2 October 1713, the first of at least five surviving children of the Scottish poet and bookseller Allan Ramsay (1684–1758) and his wife, Christian Ross (d. 1743).

Early training

Ramsay grew up surrounded by books and from 1726 he attended the Edinburgh high school, where he acquired a good knowledge of Latin and French. To these would be added eventually Greek, Italian, and German. He was drawing ‘since he was a dozen years old’ (Ramsay sen. to John Smibert, 10 May 1736, Brown, ‘Ramsay's rise’, 221) and before he was sixteen he drew a most accomplished head of his father (Scot. NPG) which was later engraved as the frontispiece for subsequent editions of his father's Poems. In 1729 he enrolled at the new (but short-lived) artists' Academy of St Luke in Edinburgh and by July 1732 he was in London studying under Hans Hysing. Although he had left by September 1733, Ramsay learned much of the painting of drapery and the use of gesture from his master.

Between 1732 and 1736 Ramsay was practising as a portrait painter in Edinburgh and of the few pictures which may now be identified from this period, Kitty Hall of Dunglass, later Mrs Hamilton (City Art Centre, Edinburgh) shows a lively professional competence. Ramsay benefited considerably from his father's connections. He met the virtuoso Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, who commissioned copies from him, and in 1733 and 1734 assisted with the design of the remarkable octagonal Guse-Pye (or Goose Pie) house (intended for his father's retirement, but transferred to his son in 1741), at the top of Castlehill in Edinburgh. In 1735 his father was soliciting the help of the provost of Edinburgh to send his son, now painting ‘like a Raphael’ (Ramsay sen. to John Smibert, 10 May 1736, Brown, ‘Ramsay's rise’, 221), to Italy to further his studies. Sir Peter Halkett Wedderburn of Gosford and Pitfirrane and his son Peter put up 2000 merks and Sir John Clerk supplied introductions to Dr Richard Mead and Dr Alexander Gordon in London who, in turn, gave further introductions and advice. By May 1736 Ramsay was ready to depart, accompanied by Alexander Cunyngham (1703–1785) (later Sir Alexander Dick, third baronet, of Prestonfield), a cultured and good-humoured Scottish physician of repute. They had resolved to speak only Italian in Italy ‘as we had been well founded in it before we left Edinburgh’ (Cunyngham's diary, Forbes, 99).

Italy, 1736–1739

Ramsay and Cunyngham were in Paris in July, when they met Cardinal de Polignac and the collector P.-J. Mariette, and proceeded south to Lyons and Marseilles in September. After a rough sea voyage from Genoa they arrived in Leghorn on 1 October. They spent three weeks in Florence, where Dr Mead had provided an introduction to the grand duke's physician and Ramsay was able to copy some of the antiquities in the ducal galleries. On 26 October they finally arrived in Rome and took lodgings on the piazza di Spagna. For three weeks they ‘did little else than scamper about every day all over the streets of the City of Rome’ (Cunyngham's diary, 15 Nov 1736, Forbes, 111). They met many of the Jacobite exiles and were introduced to the Pretender (James Stuart) and his exiled court; on 31 December they attended the birthday celebrations for Charles Edward Stuart, the Young Pretender, and in January 1737 they were admitted to the masonic lodge in the strada Paolina, whose membership was principally confined to Stuart sympathizers. Such conduct was, it appears, youthful extravagance, for both Ramsay and Cunyngham became staunch Hanoverians.

Ramsay was more serious concerning his professional advancement. He had initially been disappointed by Raphael's Stanze in the Vatican (an experience later shared by Reynolds), but he diligently pursued his studies under Francesco Imperiali and at the French Academy. After Cunyngham left Rome in March 1737, Ramsay visited Naples, where he studied briefly under the ageing Francesco Solimena, who was impressed with the portrait drawings he made of British travellers. In October he returned to Rome to stay a further six months, during which he bought, on commission from Dr Mead, a volume of seventeenth-century drawings after the antique by Pietro Santo Bartoli (probably that now in Glasgow University Library). In April 1738, accompanied by the Anglo-Italian Samuel Torriano (d. 1785), he set out north, passing through Venice, Parma, Milan, and Turin. Torriano left him at Marseilles and Ramsay arrived back in England in June 1738. Only one painting can now be associated with this first visit to Italy, the remarkable portrait of Torriano painted in Rome in 1738 (priv. coll.), which suggests Ramsay had thoroughly absorbed much of the Italian baroque convention.

London and Edinburgh, 1738–1754

By August 1738 Ramsay had taken apartments in the Great Piazza in Covent Garden, and had begun his London practice as a portrait painter. He soon achieved eminence within that crowded profession, due not only to his technical competence but also to his social and intellectual accomplishments. Dr Mead received him into the privileged circle of his dining club, and in 1740 Ramsay published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society descriptions of the recently discovered frescoes at Herculaneum, translated from the Italian of Camillo Paderni, who had been his fellow pupil under Imperiali in Rome. In 1743 he was elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. Meanwhile in December 1738 Alexander Gordon ventured to suggest that young Ramsay was ‘one of the first rate portrait painters in London, nay I may say Europe’ (Gordon to Sir John Clerk, 7 Dec 1738, Smart, Ramsay: Painter, 42). Within a year he had made his mark in society with a series of imposing whole-length portraits: the second duke of Argyll, the duke of Buccleuch, the lord chancellor, the first earl of Hardwicke, and Rachel and Charles Hamilton, the children of Lord Binning, younger brother of Lord Haddington (all in priv. colls.). He had also married in 1739 Anne Bayne, the daughter of a professor of Scots law at Edinburgh, Alexander Bayne of Rires (c.1684–1737), and Mary Carstairs (1695?–1759); they had three children who did not survive childhood and it was in giving birth to the last, on 4 February 1743, that the first Mrs Ramsay died.

In the course of the 1740s Ramsay laid the foundation of his considerable fortune. He maintained a highly practical attitude to his profession, working extremely hard and choosing his moments for self-advertisement. He was always confident of success, telling Cunyngham in 1740 that he had put the visiting French and Italian painters (J. B. Van Loo, Andrea Soldi, and Carlo Rusca) to flight and now himself played ‘the first fiddle’ (Ramsay to Cunyngham, 10 April 1740, Forbes, 142). A self-portrait of this time (NPG) illustrates this self-belief, with its clear gaze and Italianate stylishness. A constant flow of commissions led him to employ a drapery painter, Joseph van Aken (or van Haeken; c.1699–1749) , whose expert services he shared principally with Thomas Hudson, his only serious English rival. While this practice at times resulted in a certain monotony, particularly with modest half lengths, it enabled Ramsay to maintain an extraordinary level of production. From this first decade 300 portraits survive, more than half his total output. The decade closed, as it had begun, with outstanding whole-length portraits, three of which were destined for semi-public display. In 1747, following the example of Hogarth, he presented to Thomas Coram's Foundling Hospital in London a portrait of his patron Dr Mead; in 1748 he gave to the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary a whole length of the second earl of Hopetoun, and in 1749 he painted a dramatic portrait of the third duke of Argyll for the Glasgow city council. All three portraits remain in situ. A fourth imposing whole length, of the twenty-second chief of MacLeod painted in 1747 to 1748, in which the pose of the Apollo Belvedere is disguised with check trews, was dispatched to Dunvegan Castle on the Isle of Skye.

Ramsay never forgot Scotland and three visits he made between 1745 and 1748 may serve to chart his social progress. He was in Edinburgh when the Young Pretender entered on 16 September 1745 and when the Guse-Pye house was briefly threatened as a site of strategic importance; but during this visit of perhaps three months he displayed a practical tolerance towards his sitters, who included the wife of the solicitor-general, Mrs Robert Dundas, and Lord and Lady Ogilvy, the most enthusiastic Jacobites (all in priv. colls.). It was on this visit to Edinburgh that Ramsay also painted Charles Edward, the Young Pretender, most probably in October 1745. The portrait, which is in the collection of the earl of Wemyss, was categorically identified as a likeness of Charles in 2014. The only known likeness of the Young Pretender made while he was in Britain, it was engraved by Robert Strange and became an important image of Jacobite propaganda in 1745–6. Ramsay was next in Scotland in the late summer of 1747, staying until January 1748, during which time he bought a small estate in Fife, becoming known as a laird, Allan Ramsay of Kinkell. In the autumn of 1748 he spent three weeks at Inveraray Castle as the guest of the third duke of Argyll, ‘the king of Scotland’.

In July 1749 Ramsay and Hudson acted as pallbearers at van Aken's funeral. While the effect of his passing should not be exaggerated, the next five years saw pronounced changes in Ramsay's art and his emergence as a political essayist. He also married a second time, in Edinburgh on 1 March 1752, Margaret Lindsay (d. 1782), daughter of Sir Alexander Lindsay of Evelick, a kinsman of the earl of Balcarres, and his wife, born Amelia Murray, daughter of the fifth Viscount Stormont and sister of William Murray, who became the celebrated Lord Mansfield. They married without the consent of her parents who, despite the approval of Lord Balcarres, who told Ramsay he was ‘very glad to hear you have got my fair cousin’ (Balcarres to Ramsay, 12 March 1752, Smart, Ramsay: Painter, 95), remained opposed to the match. Ramsay was already maintaining a daughter from his previous marriage and helping his two surviving sisters, but he assured Sir Alexander that he could furnish his wife with an annual income of £100 which would grow ‘as my affairs increase, and I thank God, they are in a way of increasing’; he had no motive for marriage ‘but my love for your Daughter, who, I am sensible, is entitled to much more than ever I shall have to bestow upon her’ (Ramsay to Lindsay, 31 March 1752, Smart, Ramsay: Painter, 96 n. 10). There were three surviving children from their long and happy marriage, Amelia (1755–1813), Charlotte (1758–1818?), and John (1768–1845).

The Ramsays were in London until the end of 1753 when they moved to Edinburgh until June 1754. Ramsay's portraiture now assumed a new informality, approaching Hogarth's naturalism, but also much affected by the contemporary French manner. When he painted the Wemyss sisters, Lady Helen and Lady Walpole, in 1753 (both priv. coll.), Ramsay remarked that ‘les joues de My Lady Nelly Wemyss parlent Francois’ (Smart, Ramsay: Painter, 110). Among other outstanding works from this time are Thomas Lamb, of 1753 (National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh), and Hew Dalrymple, Lord Drummore, of 1754 (Scot. NPG). David Hume also sat to him in Edinburgh in 1754 (priv. coll.), the portrait marking a friendship based on mutual intellectual respect. In 1754 Ramsay, Hume, and Adam Smith founded in Edinburgh an exclusive debating club, the Select Society. It first met on 22 May, with Hume as treasurer, and the rules laid down that the society could debate any subject ‘except such as regard Revealed Religion, or which may give occasion to vent any Principles of Jacobitism’ (‘Rules and orders of the Select Society’, MS, NL Scot.). At this time Ramsay was advising Hume on the first volume of his History of England (published in 1754), particularly on his assessment of Shakespeare. He was himself already beginning to publish essays which would continue to appear as occasional and anonymous pamphlets throughout the rest of his life.

In 1753 there had appeared On Ridicule and Concerning the Affair of Elizabeth Canning. The former, concerning the use of ridicule as a test of truth, Ramsay advertised as ‘tending to show the usefulness, and necessity of experimental reasoning in philological and moral enquiries’; while excusing himself as ‘one whose necessary studies have been of a nature little connected with deep erudition’, Ramsay reminded his readers that ‘printing was discovered by a soldier, and gunpowder by a monk’ (Smart, Ramsay: Painter, 98). Elizabeth Canning defended one Mary Squires against a sentence of death passed at the Old Bailey on evidence supplied by Elizabeth Canning, and it contained an impressive display of logic involving a discussion of the words ‘improbability’ and ‘impossibility’, much in the manner of Hume. The prisoner was afterwards released. Ramsay's pamphlet was to come to the notice of Voltaire, who was pleased to describe the author as a philosophe. In 1754 there appeared as The Investigator: Number CCXXI (a whimsical statistic) the Essay on the Naturalization of Foreigners, advocating that ‘every man who lived in England would be an Englishman to all intents and purposes’.

In 1755 (when Ramsay was already in Italy) The Investigator: Number CCXXII (a further whimsy) published the most important of his writings, A Dialogue on Taste. It appeared two years after Hogarth's Analysis of Beauty, and was an altogether more disciplined performance. Ramsay described how fashion arose from the pleasures of the rich and powerful; how the eye is frequently pleased by what is ‘the reverse of consistency’—as the darkening of the principal apartments of the new Mansion House in London ‘by clapping before the windows stately pillars which support nothing or, which is much the same, nothing of any use’; on the other hand the ‘vastly natural’ quality of a portrait by Quentin de La Tour, a country house view by Lambert, or Hogarth's March to Finchley was appreciated by ‘the lowest and most illiterate of the people’; he maintained the superiority of Greek architecture over the Roman (the Romans being mischievously described as ‘a gang of meer plunderers, sprung from those who had been, but a little while before their conquest of Greece, naked thieves and runaway slaves’) and of Gothic architecture over contrived post-Renaissance classicism (which was in effect a misapplication of Greek principles). In April or May 1755 Hume told Ramsay that his essay ‘has met with a very good reception from the wits and the critics … they told me it was very entertaining, and seemed very reasonable’ (The Letters of David Hume, ed. J. Y. T. Greig, 1932, 1.221). Horace Walpole soon noticed Ramsay as ‘a very agreeable writer’ with ‘a great deal of genuine wit and a very just manner of reasoning’ (Walpole to Sir David Dalrymple, 25 Feb 1759, Horace Walpole's Correspondence, ed. W. S. Lewis, 1951, 15.47). Hogarth amicably announced that purchasers of his own Analysis of Beauty would be given copies of A Dialogue on Taste, ‘written by A.R., a friend of Mr Hogarth and eminent portrait painter now at Rome’ (Smart, Ramsay: Painter, 101).

Italy, 1754–1757

Ramsay, accompanied by his wife and sister Catherine, had left London in July 1754 and reached Italy in October. As on his previous visit to Italy, Ramsay spent two months in Florence, copying in the ducal galleries, before arriving in Rome in December. He took rooms on the Viminale Hill, ‘to seclude myself a good deal from the English travellers without falling out with any of them, and to preserve the greater part of my time for painting, drawing and reading’ (Fleming, 147). He held weekly conversazioni for British visitors and attended those given by the young and ambitious Robert Adam, who considered the Ramsays worthy company ‘as Mrs Ramsay is of so good a family and Mumpy himself so rich’ besides being ‘generally known and regarded’ (Fleming, 121, 174). Ramsay and Adam were quickly familiar with the Abbé Peter Grant, the Roman agent of the Scottish Catholic mission far better known for his unctuous attendance on wealthy tourists, and Robert Wood, the renowned eastern traveller then accompanying the duke of Bridgewater in Rome. Together they formed an unofficial Caledonian Club, gossiping in ‘ain Mither tongue’ (Fleming, 171).

Ramsay painted Robert Wood (NPG) and General John Burgoyne (priv. coll.), while the portrait of his wife holding a parasol (priv. coll.) must have been painted soon after the birth of their first child, Amelia, in March 1755. Ramsay also copied paintings by Domenichino and Batoni (whom he came to know well), and sketched Roman antiquities with the French artists Clérisseau and Pêcheux. He made a considerable number of life studies (National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh) at the French Academy which prompted Adam to observe that Ramsay ‘knew less about the proportions of the human figure than any young boy about Rome’ (Fleming, 174). There was always an element of striving about Ramsay's art and, perhaps to vindicate himself, Ramsay had his pupil David Martin bring out to Rome a number of his drawings to be shown at the Accademia di San Luca.

The study of antiquity increasingly occupied his time, and Ramsay formed an unlikely friendship with the Venetian engraver, designer, and antiquarian G. B. Piranesi (‘the most extraordinary fellow I ever saw’, said Adam; Fleming, 165). They argued about the respective merits of Greek and Roman classical architecture, but Piranesi saw fit to include a generous tribute to him in one of his capricci in Le antichità Romane (1756), in which a tomb appears (visibly) inscribed to Allan Ramsay: ‘Scoti Pictor et in omni liberal artium facultae celeber’. Later in 1761 Piranesi attacked Ramsay in his Della magnificenza ed architettura de' Romani for having so wilfully misrepresented the achievements of the Romans and their architects in his Dialogue on Taste.

Ramsay paid a visit to Naples and sketched what was then thought to be Virgil's tomb at Posillipo, and while he stayed at the Villa d'Este in Tivoli in the summer of 1755 he began his search for the site of Horace's villa, a task which was to occupy him increasingly in later years. In the summer of 1756 Ramsay was taken ill and convalesced at Viterbo, but he was fit enough when he left Rome in May 1757. Again he stopped at Florence, where he copied the portrait of Galileo by Sustermans for the master of Trinity College, Cambridge. Late in August 1757 the Ramsays were back in London.

Royal patronage

Ramsay now took up residence at 31 Soho Square, a fashionable area of Westminster, and entered upon the most distinguished episode of his professional career. His compatriot the third earl of Bute (a nephew of the third duke of Argyll) was now the prince of Wales's governor, and he commissioned from Ramsay a whole-length portrait of his royal pupil (Mount Stuart, Rothesay, Isle of Bute). Within weeks of his return from Italy, on 12 October 1757, Ramsay attended the prince at Kew for the first sitting. The portrait was admired and the prince in turn commissioned a whole length of Lord Bute (National Trust for Scotland, Edinburgh). After the prince ascended the throne in October 1760 as George III, with Bute as his favourite minister, he turned to Ramsay to paint his coronation portrait and that of his queen, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, whom he married in September 1761. These elegant state portraits (Royal Collection), the most impressive of British monarchs since Van Dyck, were completed by March 1762. Meanwhile Ramsay's position as painter to the king was criticized as a flagrant instance of undue Scottish influence, and was further complicated by the almost unnoticed survival of the previous, unimpressive incumbent, John Shackleton. In December 1761 Ramsay was appointed ‘One of His Majesty's Painters in Ordinary’, duly succeeding as ‘Principal Painter in Ordinary to the King’ upon Shackleton's death in March 1767. His relations with the king and queen were, it seems, relaxed, and he was the only courtier able to speak with them in German. In January 1762 he was ordering German books, ‘matters of entertainment or Belles Lettres’, by Lessing, Rabener, Gellert, Gessner, and Hagedorn (Ramsay to an unknown correspondent, 4 Jan 1762, Brown, Ramsay's Rise, 212).

From 1762 until his death in 1784 Ramsay was responsible for supplying at least 150 pairs of portraits of George III and his queen, either for the royal family, or for the lord chamberlain for distribution to government representatives abroad. He received 80 guineas for each portrait, so that his private fortune, already remarked upon by Adam in 1755, now increased considerably. He originally intended to ‘give the last painting’ of each replica himself but his resolve soon gave way. Joseph Moser recalled seeing his studio

crowded with portraits of His Majesty in every stage of operation. The ardour with which these beloved objects were sought for by distant corporations and transmarine colonies was astonishing; the painter with all the assistance he could procure could by no means satisfy the diurnal demands that were made in Soho Square upon his talents and industry. (European Magazine, 64, 1813, 516)

In 1764 Ramsay acquired a more spacious house at 67 Harley Street where coachmen's rooms and haylofts were converted into a long gallery to facilitate production. His principal assistants were David Martin (1737–1797) and Philip Reinagle (1749–1833), who received up to 25 of the 80 guineas Ramsay was being paid for each picture.

Apart from the coronation portraits Ramsay painted profile half lengths of the king and queen, and a fine whole-length portrait of the queen with the two young princes, George and Frederick, between 1764 and 1767 (Royal Collection). For Lord Bute he painted, about 1764, a whole length of his particular friend, the king's mother, Augusta, the dowager princess of Wales (Mount Stuart, Rothesay, Isle of Bute). But royal portraiture was not an exclusive occupation, and many of Ramsay's finest portraits date from the ten years after his return from the second visit to Italy. Delicate colour and a French elegance lend them particular distinction. The beautiful picture of his wife holding a flower (National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh), his portraits of Lady Holland, Lady Coke, Mrs Elizabeth Montagu, and Lady Susan Fox-Strangways (all priv. coll.) provide ample evidence for Horace Walpole's comment that Ramsay, ‘all delicacy’, was ‘formed to paint women’, in contrast, he thought, to Reynolds, who seldom succeeded with them (Walpole to Sir David Dalrymple, 25 Feb 1759, Horace Walpole's Correspondence, ed. W. S. Lewis, 1951, 15.47). Ramsay's double portrait of Walpole's nieces, Laura Keppel and Lady Huntingtower (priv. coll., USA), painted in 1765, remains, perhaps, his masterpiece. In 1766 Ramsay painted the remarkable half lengths of his friend David Hume (Scot. NPG), full face in a bright scarlet coat, and Hume's temporary charge in England, the exiled Jean-Jacques Rousseau, dressed in dark Armenian fur and looking askance (National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh). These are profound studies of character and Rousseau's subsequent disenchantment with his portrait may be construed as a compliment to Ramsay's grasp of his instability.

Such elegant pictures lacked the grandiloquence which, as Reynolds understood, was becoming necessary for the effective exhibition picture. Ramsay never exhibited, although he had been elected a member of the Society of Arts in 1757 and became a vice-president of the Society of Artists in 1765; nor did he join in the various campaigns for annual exhibitions in London. Ultimately it was Reynolds who became the president of the Royal Academy in 1768. Ramsay's attitude to painting was very different from that of his earliest London years. Now he could choose his sitters; as the king's painter he was no longer a competitor, and he was financially independent. Moreover his ambitions were no longer wholly focused on his painting; travel, writing, and classical scholarship increasingly occupied his time.

Final years

In September 1765, accompanied by his wife and eldest daughter, Amelia, Ramsay spent ten days in Geneva with Lord Stanhope, a mathematician of repute and a long-standing patron, and his wife, a sister of the earl of Haddington, who was suffering from a fractured thigh. From Geneva he took the opportunity of visiting Voltaire at Ferney. On their return journey they spent two weeks in Paris, where, apart from his familiarity with painters, Ramsay saw Hume, then attached to the British embassy, and Horace Walpole, confined to his rooms with gout. He was introduced to Baron d'Holbach and to Diderot, who called him philosophe—‘on dit qu'il peint mal, mais il raisonne très bien’ (D. Diderot, Œuvres complètes, 19, 1876, 174); Ramsay entered into correspondence with him.

In 1766 Ramsay spent six months in Edinburgh where, as a freeholder in the shire of Kinross, he engaged in two minor legal disputes with his customary punctiliousness, a quality which continued to inform his essays. His previous pamphlets had been revised and reissued as The Investigator in 1762, and over the next ten years further political essays appeared essentially adhering to the king's high tory policies. An Essay on the Constitution of England appeared in 1765, a defence of the liberties enjoyed by the English people under Hanoverian rule. In an appendix he transcribed and discussed the original articles of the Magna Carta, showing how it was influenced by popery and concepts of arbitrary power. Ramsay had inspected the original articles through a manuscript he had discovered in a private collection and which, through his advocacy, was presented to the British Museum in 1769. Ramsay's essay was well received, being translated into German in 1767 with the author's name on the title-page. There followed in 1769 Thoughts on the Origin and Nature of Government, written in 1766, expressing serious concern over the threatened loss of the American colonies, but defending the right to tax them. In 1772 he published two essays on the necessity of government intervention in the affairs of the East India Company, of which he was a prominent shareholder: An Enquiry into the Rights of the East India Company of Making War and Peace, and A Plan of the Government of Bengal. The latter contained a letter from Ramsay to the prime minister Lord North, dated 20 March 1772, and the text of a speech given by Ramsay to the general court of the East India Company on 12 November 1772.

Early in 1773 Ramsay suffered a permanent injury to his right arm through a fall which effectively ended his career as a painter, although his activity had been reduced for several years. Later that year, with his sister Janet, he returned to Geneva to see Lady Stanhope, who was now disabled. Again he visited Voltaire at Ferney, this time accompanied by the young fifth earl of Chesterfield. Ramsay himself now began to suffer from rheumatic pains and in 1775, with his wife and daughter Amelia, he returned for a third time to Italy, hoping to effect a cure. But the waters at Pisa and Casiano proved ineffectual, the latter being like those of ‘Tunbridge Wells, but twenty times stronger’ (Ramsay to Sir John Pringe, 22 Nov 1775, Ingamells, 798). With more success he tried the baths on the island of Ischia and he began to draw again; drawings of himself and his wife dated 1776 are in the National Gallery of Scotland. But Ramsay was principally engrossed with antiquarian pursuits (Fuseli commenting on his fondness for ‘tracing on dubious vestiges the haunts of ancient genius and learning’; Smart, Ramsay: Painter, 244) and soon became obsessed with the site of Horace's Sabine villa which he believed, probably correctly, to have been at Licenza. Count Orsini lent him rooms in his palace there, the young Jacob More made drawings for him, and his wife acted as amanuensis. ‘An enquiry into the situation and circumstances of Horace's Sabine villa, written during travels through Italy in the years 1775, 1776 and 1777’ is preserved in two manuscripts in the University Library, Edinburgh, and in the National Library of Scotland.

The Ramsays left Rome in June 1777 and were back in London by October. More essays followed. In 1777 appeared Letters on the Present Disturbances in Great Britain and her American Provinces, originally published in the Public Advertiser (18 April 1771; 25, 26 January 1775). A Succinct Review of the American Contest was first published in February 1778. A Letter to Edmund Burke, dated 13 March 1780, answered that statesman's speech concerning government expenditure and the need for economic reform; the present system, wrote Ramsay, was ‘the popular or democratic system, and the most popular and democratic that was ever seen in any empire so rich and extended as ours’. The Gordon riots of 1780 induced Observations on the Riot Act by a Dilettante in Law and Politics in 1781, advocating a strengthening of legislation for the protection of life and property.

Ramsay was now part of London's intellectual society and there are glimpses of him in the Reynolds–Johnson–Boswell circle between 1778 and 1780. On 9 April 1778 Ramsay spoke at length on Horace's villa at a dinner given by Reynolds with Johnson, Boswell, and Edward Gibbon among the guests. Soon afterwards Boswell implored Ramsay to write the biography of his father the poet—but only a brief manuscript account survives (published in The Works of Allan Ramsay, 1686–1758, 4, ed. A. M. Kinghorn and A. Law, 1970, 71–5). On 29 April Ramsay hosted a dinner for Reynolds, Boswell, and Johnson, at which the conversation ranged over Alexander Pope, Homer, and Robert Adam; on the next day Johnson declared: ‘I love Ramsay. You will not find a man in whose conversation there is more instruction, more information, and more elegance, than in Ramsay's’ (Boswell, Life, 3.336). His conversation was more than once described as lively, and even his military son-in-law (who became Sir Archibald Campbell of Inverneil) described ‘the famous Allan Ramsay’ with some affection as the ‘old Cadger’ who was ‘Rich and Highly respected; a most Sensible, Pleasing, Clever Old man’ (Smart, Ramsay: Painter, 259).

Mrs Ramsay died on 4 March 1782 and that summer Ramsay resolved to return to Italy for his fourth and last visit, ‘to alleviate his bodily infirmities, by change of climate, and to dissipate the melancholly occasioned by the loss of one valuable part of his family, and the dispersion of others’ (advertisement to ‘Horace's Sabine Villa’ MS, Edinburgh University Library), both his daughters having gone to the West Indies with Amelia's military husband. Ramsay was accompanied by his son, the fourteen-year-old John Ramsay, who kept a journal (MS, NL Scot.), describing how he transcribed classical texts and read Latin texts to his now fragile and demanding father. In April 1783 he spent two months in Naples, where the distinguished British minister Sir William Hamilton played him Handel sonatas, receiving in return a copy of Ramsay's last pamphlet. The Essay on the Right of Conquest, just published in Florence, was a slightly jaded rationalization of imperial expansion. Ramsay continued his study of Horace's villa, again staying in Count Orsini's palace at Licenza in September 1783, while the German artist Philipp Hackert, then painter to the king of Naples, made ten views, including a map, of the site. In October 1783 Ramsay and his son went to Florence, their visit marked by the attentions of the aged Sir Horace Mann and the rather unworthy verses which Ramsay was persuaded by the poetaster Robert Merry to have published in The Arno Miscellany in 1784. Horace Walpole told Mann this was the act of ‘an old dotard … sporting and playing at leap frog, with brats!’ (Walpole to Mann, 8 Nov 1784, Horace Walpole's Correspondence, ed. W. S. Lewis, 1951, 25.540). In the summer of 1784 Ramsay resolved to return home, primarily to see his daughters, then about to return to England. But the journey proved too much, and he died on arrival at Dover, on 10 August 1784. He was buried in St Marylebone Church, Middlesex.

Conclusion

Ramsay was a portrait painter of great distinction. Within the history of British art he appears a sophisticated artist, conversant with contemporary Italian and French practice, and at his best in the 1750s and 1760s. Both Reynolds and Gainsborough learned from his example. After his death British painting came to be dominated by the more imaginative, and often more heroic, paintings shown at the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy, and it was only in the mid-twentieth century that Ramsay's refined elegance was again properly appreciated. Ramsay's other interests, his classical scholarship and his political essays, must now be accounted minor in comparison, but they set him apart from other painters of his time and showed the breadth of his understanding. One of the last portraits of Ramsay, the marble bust by Michael Foye carved in Rome from 1775 to 1777, shows a determined, level-headed elderly man with a set, down-turned mouth—the ‘Old Mumpy’ expression which Robert Adam had described (Scot. NPG); it seems a far cry from the handsome and ambitious self-portrait of his young manhood, but it is draped with a toga, suggestive of that Roman gravitas and steady spirit which characterized his life.

John Ingamells DNB