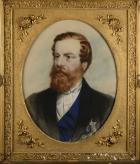

middle right "By Mr Barrable"

Henry Pelham Fiennes Pelham-Clinton, , fifth duke of Newcastle under Lyme (1811–1864), politician, was born on 22 May 1811 at 39 Charles Street, Berkeley Square, London, the third child but eldest son of Henry Pelham Fiennes Pelham-Clinton, fourth duke of Newcastle under Lyme (1785–1851), and his wife, Georgiana Elizabeth (1789–1822), daughter of Edward Miller Mundy of Shipley, Derbyshire. Styled the earl of Lincoln until 1851, he was educated at Eton College (1824–8), and in 1829 proceeded to Christ Church, Oxford, where he took a BA degree in 1832. While at Oxford he became a close friend of William Ewart Gladstone; both belonged to the Union Debating Society, each serving as president, and both were members of the Essay Club, founded as an Oxford equivalent to the Cambridge Apostles. He also shared Gladstone's high-church Anglicanism.

Both Lincoln and Gladstone entered parliament as Conservatives in December 1832 through the influence of the fourth duke of Newcastle, the former, without a contest, for South Nottinghamshire and the latter for Newark. On 27 November 1832, shortly before his election, Lincoln married Susan Harriet Catherine (1814–1889), daughter of Alexander Douglas-Hamilton, tenth duke of Hamilton, granddaughter of William Beckford, and sister of William Douglas-Hamilton, later the eleventh duke, an Eton and Oxford friend of Lincoln. He served as a lord of the Treasury from 31 December 1834 to 20 April 1835 in Sir Robert Peel's first ministry. It was at this time that a lasting bond of friendship was established between Peel and his young subordinate colleagues, whom he had introduced to official life.

Lincoln became first commissioner of woods and forests on 15 April 1841 when Peel formed his second administration. As commissioner he performed a myriad of tasks, including providing more public accessibility to royal buildings and parks; enacting the major recommendations of the metropolitan improvements commission, over which he served as chairman; enlarging Buckingham Palace; and superintending the work of the British Geological Survey. Following Gladstone's resignation over the Maynooth College grant early in 1845, Peel appointed Lincoln to the cabinet; and on 14 February 1846 he was made chief secretary for Ireland in Peel's reconstituted administration. The potato famine had become catastrophic by the time he arrived in Ireland. Despite opposition to large-scale state assistance from Treasury officials, especially Charles Edward Trevelyan, he helped to set in motion famine relief measures that included a programme of public works to create employment to enable the Irish people to purchase imported grain. He also became a principal proponent for larger measures to stimulate economic growth and reconstruct Irish society. Although modest, the famine relief measures prevented exceptional suffering during the first half of 1846; but his tenure as chief secretary ended when the Peel ministry resigned in June 1846.

By the time of his appointment as chief secretary Lincoln had modified his earlier protectionist views and was in complete agreement with Peel over the necessity of repealing the corn laws. Peel acknowledged the support he received from Lincoln during the contest over corn law repeal, and the obloquy and sacrifice which this had involved. He suffered his father's wrath for supporting repeal, having already angered him by his support for the Maynooth grant. When he had to seek re-election for his South Nottinghamshire seat on accepting the Irish chief secretaryship, he was defeated by a protectionist candidate backed by his father. His father-in-law, however, helped to find him a seat, Falkirk burghs, for which he was elected in May 1846. The crisis strengthened his devotion to Peel and separated him irrevocably from many of his earlier political positions, as well as from his father.

During the late 1840s Lincoln and the other leading Peelites tried unsuccessfully to get Peel to resume leadership of a moderate political party. Following Peel's death in 1850 Lincoln's own political ambitions were raised. His devotion to public service and his capacity for hard work earned him recognition, and a few prominent individuals, including Prince Albert, the prince consort, encouraged him to seek the leadership of a coalition of Peelites and liberal whigs. Although Lord Aberdeen, rather than Lincoln, was selected to head the coalition government when it was formed in December 1852, many regarded him as the major spokesman of Peelite political philosophy and the most likely successor of Lord Aberdeen as prime minister. A series of misfortunes, however, including his tragic marriage, prevented him from fulfilling his political ambitions and left him with shattered health and a damaged official reputation.

Lady Lincoln [see Opdebeck, Lady Susan Harriet Catherine], who bore him four sons and a daughter, had a series of affairs, which led to several separations and reconciliations between the couple. After a period of reconciliation during 1844–7, she finally left on 2 August 1848 and travelled on the continent in the company of Lord Horatio Walpole, with whom she had a child a year later. This, and the failure of Gladstone's mission to Italy in the summer of 1849 to persuade Lady Lincoln to return to her husband and children, obliged Lincoln to seek a divorce. On 14 August 1850 the marriage was formally dissolved by act of parliament (with Gladstone giving evidence). Lincoln's father, from whom he had also become estranged, died early in the following year, and he succeeded (12 January 1851) both to the title, as fifth duke of Newcastle, and to estates which were encumbered with debt.

Newcastle was secretary for the colonies in Aberdeen's administration from December 1852 until June 1854, when the outbreak of the Crimean War necessitated the creation of a separate department for administering military affairs. His administrative difficulties began when he took over this newly created office as secretary of state for war. Newcastle laboured indefatigably throughout the summer and autumn to see that the army was as well equipped and prepared as the capabilities of the country allowed, knowing all the while that the system of military administration was in a hopeless state of disorganization and confusion. Despite these problems and administrative shortcomings, the army at the time of the Crimean invasion was more than sufficiently supplied and equipped. Nevertheless, circumstances largely beyond Newcastle's control brought near disaster to the British army in the Crimea during the winter of 1854–5. Although the duke cannot be exonerated completely, an objective review of his administration of the War Office clearly reveals that no individual was solely responsible for the failures. The mistakes and miscalculations of the civilian authorities in London were compounded by those of the military men in the Crimea. However, it was more a failure of strategy and military execution than one of logistics that nearly lost the army; and it was Newcastle's misfortune to be placed at the head of a weak and corrupt system without sufficient authority or opportunity to make it more workable. For his failures he suffered the wrath of the nation early in 1855. He resigned in disgrace on 1 February 1855.

Even before his resignation Newcastle had effected, perhaps belatedly, many of the measures that would rectify the difficulties for the army in the Crimea, including the construction of the Balaklava railway, establishment of the Land Transport Corps, and the appointment of the hospitals commission. Lord Panmure candidly stated that ‘the barometer was steadily on the rise’ (Munsell, Unfortunate Duke, 216) when he took over the War Office from the duke and that he had little to add to the measures that had already been initiated by his predecessor for improving the condition of the army. Yet Panmure and Lord Palmerston, the new prime minister, received all the credit for the improvement of the army, and the duke continued to be pilloried by the press and subjected to parliamentary censure for conducting the war without sufficient care and forethought. Rather than remain in England to resist the motion of censure, the duke accepted Palmerston's invitation to go to the East to report on the state of the army in the Crimea and the hospitals in Turkey.

Much of the rancour against Newcastle had disappeared by the time of his return to England late in 1855. None the less, still bitter over his past treatment, he semi-retired from politics. His close friend Lady Frances Waldegrave promoted him as a possible Liberal leader to succeed Palmerston; for his part Newcastle looked to Lady Waldegrave, then married to a third, elderly husband, as a possible second wife. In the event neither objective was achieved. He was also distracted by domestic worries. His eldest son rebelled against his strict upbringing and turned out a wastrel, fleeing the country to escape vast gambling debts. Newcastle's determination to prevent his daughter, Susan, from inheriting the characteristics of her mother, merely drove her into an elopement with a drunken and violent husband, Lord Adolphus Vane. His third son, Arthur, deserted from the navy in 1864 and died in 1870 while awaiting trial on charges of indecency in the case involving Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park. With the exception of his second son, Edward (who became master of the queen's household), Newcastle's record as a father was disastrous.

In June 1859 Newcastle joined the Palmerston cabinet as colonial secretary, a position for which he was well suited. As a decided imperialist who administered the empire with tact and understanding in an innovative way, he became a highly regarded colonial secretary. He greatly accelerated the transfer of governmental responsibility to the settlement colonies of North America, Australia, and New Zealand, a process which he believed was necessary to save the empire. To him it was in the best interests of Great Britain to foster communities overseas (he was a member of the Canterbury Association) and to tie them to the mother country with ‘bonds of mutual sympathy and mutual obligation’ (Munsell, Unfortunate Duke, 243). His administration of the Colonial Office provided many valuable precedents that were extremely important in the evolutionary process from empire to Commonwealth.

In 1860 Newcastle served as an official adviser and leader of the entourage accompanying the prince of Wales to British North America and the United States. The duke also chaired the royal commission on popular education (1858–61), the recommendations of which were partially incorporated in the revised code of 1862 and the Education Act of 1870. Other offices and honours that Newcastle held or received included high steward of Retford (1851), lieutenant-colonel commandant of the Sherwood Rangers (1853), lord lieutenant of Nottinghamshire (1857), lord warden of the stannaries (1862), honorary DCL of Oxford (1863), councillor to the prince of Wales (1863), and a knight of the Garter (1860).

Contemporary assessments of Newcastle varied widely. To the duke of Argyll, a fellow Peelite and ministerial colleague, ‘Newcastle was an industrious and conscientious worker, but he had no brilliancy and little initiative’ (G. Douglas, eighth duke of Argyll, Autobiography and Memoirs, 2 vols., 1906, 1.380). Frederic, Lord Blachford, long-time under-secretary of state for the colonies, described the duke as ‘an honest and honourable man’ who in political administration was ‘painstaking, clear-headed and just’, but whose abilities were far too insufficient ‘for the management of great affairs—which, however, he was always ambitious of handling’. Newcastle was also standoffish and overcritical of others, and although he respected other people's positions, he was always sensible of his own. ‘It was said of him’, Blachford added, ‘that he did not remember his rank unless you forgot it’, an expression that aptly described the duke's relations to subordinates (Rogers, 225).

Despite these judgements, Newcastle was highly regarded by some of the most prominent of his contemporaries, including the prince consort, a close friend. In the early 1850s Gladstone and Lord Aberdeen believed that the duke would some day head a government. Gladstone always respected Newcastle and sought his opinions on political and religious matters. Only towards the end of the duke's life did Gladstone see a decline in the abilities that he believed had distinguished the duke more as a statesman than as an administrator. Lord Palmerston regarded Newcastle as an excellent colonial secretary; in 1864, when failing health forced the duke to retire, Palmerston waited as long as he could before accepting his letter of resignation.

Suffering a rapid deterioration of health following his resignation from office in the spring, Newcastle died at Clumber Park, Nottinghamshire, his principal residence, from a cerebral haemorrhage on 18 October 1864. He was buried in the family mausoleum at Markham Clinton. He left his estates in financial disarray, which Gladstone and Frederick Ouvry, as executors and trustees, spent years disentangling. The fortitude with which Newcastle had borne accumulated misfortune and torturing disease touched those who knew him. Gladstone believed that the life of the unfortunate duke was so tragic that it was best forgotten. Fortunately, however, historians in the late twentieth century have rescued Newcastle from obscurity to place both his failures and accomplishments into historical perspective. Earlier accounts that were overly critical of his career, particularly his administration of the War Office, have been corrected, and he has now been allowed to take his place in history as an important political figure during the period of the 1840s through the early 1860s and as one of the most effective colonial secretaries of the nineteenth century.

Darrell Munsell DNB