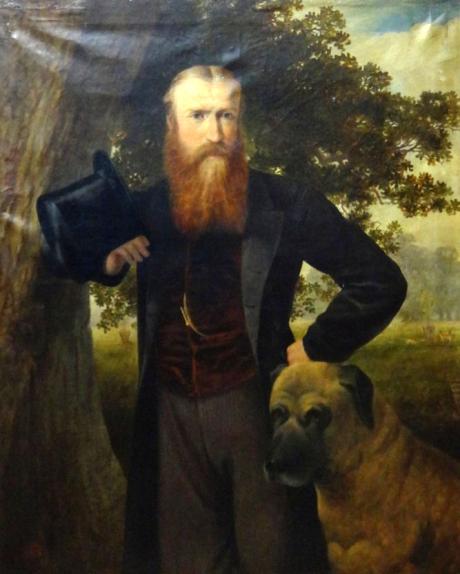

signed with monogram and dated "1868"

It is possible that the backdrop to this portrait shows part of Wimbledon Common which was part of Spencer's manor of Wimbledon. In 1864, Spencer, as lord of the manor of Wimbledon through his ownership of Wimbledon House, attempted to get a private parliamentary bill to enclose Wimbledon Common for the creation of a new park with a house and gardens and to sell part for building, it would have meant enclosing 700 acres as a park and sell off a further 300 acres as building land.The plan encountered stiff local opposition led by Sir Henry Peek. Eventually,In a landmark decision for English common land, and following an enquiry, permission was refused and a board of conservators was established in 1871 to take ownership of the common and preserve it in its natural condition and to ensure that the Common remains unbuilt upon and open to all for. In return for an annuity of £1,200, the Earl gave up his rights under the Wimbledon and Putney Commons Act of 1871.

Unitetifiled sale room, lot 263, 3rd May 1978

Spencer, John Poyntz, fifth Earl Spencer (1835–1910), politician and viceroy of Ireland, was the son of Frederick Spencer (1798–1857) [see under Spencer, Sir Robert Cavendish], a distinguished naval captain, who became fourth Earl Spencer on his brother's death in 1845. As member of parliament for Worcestershire and Midhurst, Sussex, between 1831 and 1841, Frederick invariably voted with the whigs. In this he followed the tradition of his elder brother, John Charles Spencer, third earl, who was chancellor of the exchequer in Grey's ministry from 1830 and played a leading part in the passing of the Reform Bill two years later. Frederick had married Elizabeth Georgiana Poyntz of Midgham House, Berkshire, and Cowdray Park, Sussex, in 1830, and there were three children, Georgina, Sarah, and a boy, John Poyntz, born on 27 October 1835 at the family's London mansion, Spencer House. Their mother died in 1851 and the fourth earl married secondly Adelaide Horatia Seymour in 1854. A daughter, Victoria Alexandrina, was born in 1855 and a boy, Charles Robert (Bobby), in October 1857.

Spencer, styled Viscount Althorp until 1857, entered Harrow School in Easter 1848 and, though not prominent in his academic studies, developed his lifelong interest in cricket and took an active part in the debating society. Althorp made a number of friends, including H. Montagu Butler, later headmaster of Harrow, and Lord Frederick Cavendish. After a spell with a tutor at Brighton, Althorp went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1854 to read for a nobleman's degree. He made no mark academically—a major distraction was his growing passion for riding—and graduated MA in January 1857.

Althorp was elected for one of the two seats in the southern division of Northamptonshire in the general election of March 1857, pledging his support for Palmerston. This was followed by a three-month tour of North America, where he observed the growing tensions between the northern and southern states. He arrived back in England in mid-December: on 27th of that month his father died suddenly, and Althorp became the new Earl Spencer at the age of twenty-two.

Because of Spencer's desire to remain active in the political field on his appointment to the royal household, first as groom of the stable to Prince Albert, 1859–61, and then to the prince of Wales (later Edward VII), 1862–6, he required assurances that his participation in politics would still be possible. Spencer made a number of contributions to the debates in the Lords in the early 1860s. He was made a knight of the Garter in 1864, an appropriate acknowledgement of his gift to the nation at this time of Wimbledon Common. In the following year he chaired a royal commission to suggest means of dealing with the cattle plague. Other members of the commission included Lord Cranborne (later the marquess of Salisbury), Robert Lowe, and Lyon Playfair. He gained further experience in public life when he served on a special committee, set up in November 1867 by the War Office, to report on a suitable breech-loading rifle.

The introduction of a reform bill by Lord Russell in 1866 had led to a split among his own supporters. A group opposed to reform was led by Earl Grosvenor, Robert Lowe, and Lord Elcho in the Commons, and the marquess of Lansdowne, Earl Grey, and Lord Lichfield in the Lords. Elcho and Grosvenor tried to persuade Spencer to lead the moderate Liberal faction but he refused, expressing his confidence in mainstream Liberalism, and especially Gladstone.

Spencer's loyalty was not forgotten when Gladstone formed his ministry in December 1868. The offer of lord lieutenant of Ireland came as a surprise both to Spencer and to many others. He had previously held no official political post and had had no experience of Irish affairs. The appointment was largely due to the influence of Chichester Fortescue, later first Baron Carlingford, who had been chief secretary in 1865–6 and again in 1868, with a seat in the cabinet. Spencer's correspondence with his ministerial colleagues on the Land Bill of 1870 first displayed his grasp of the Irish problem. Himself a model landlord, Spencer favoured the restoration of goodwill between landlords and tenants. He suggested the setting up of tribunals with jurisdiction on questions of rent and proposed that tenants-at-will should enjoy a period of five to seven years at a fixed rent. Spencer regarded the Land Act as a prerequisite for settling agrarian crime and for regaining the confidence of the Irish people. This approach went further than those put forward by government colleagues, many of whom represented the landlord interest, although Fortescue, who held property in Ireland, to a large extent shared his views. However, Spencer's proposals clashed with Gladstone's principle that the state should be given as few responsibilities as possible under the Land Act.

Between the time when the bill was first discussed in cabinet in late 1869 and its introduction in the Commons in February 1870, agrarian crime rose considerably. Spencer and Fortescue pressed for greater powers to deal with crime and contemplated resignation when it seemed unlikely that the cabinet would sanction coercive legislation in Ireland. Although a Peace Preservation Bill granting such powers was rapidly enacted, matters did not go smoothly with the Land Bill. It was much weakened in the course of its passage through parliament and the act failed to pacify Ireland. A second Land Act was required eleven years later.

When Fortescue moved to the Board of Trade early in 1871, his place as chief secretary was taken by Spencer Compton, marquess of Hartington, Spencer's second cousin. At the end of 1870 Spencer believed that it was safe to release the remaining Fenian prisoners. However, there was a further outbreak of agrarian violence, especially in co. Westmeath, where secret societies flourished, and Spencer was obliged to ask for the suspension of habeas corpus. Spencer and Hartington were heavily involved in drawing up the Westmeath Bill, granting them the necessary powers. It received the royal assent in June 1871.

When Gladstone turned his attention to remodelling the Irish university education system in 1872–3, Spencer had the task of pacifying the Roman Catholic hierarchy. Hartington expressed grave dissatisfaction with the inherent contradictions in the Irish University Bill, though Spencer supported Gladstone. The bill and the government were defeated in the Commons on 11–12 March 1873. Spencer favoured resignation rather than a dissolution, a course which was agreed upon by the cabinet. However, Disraeli, not wishing to be head of a minority government, refused to take office and the Liberal administration continued, though much weakened. When the general election led to a Conservative victory in February 1874, Spencer was relieved to be out of office after five years in Ireland and returned to his country seat, Althorp, in Northamptonshire. Looking back over his time as lord lieutenant, he considered his achievements. Only two men were in prison under his warrant when he left Ireland, life and property in co. Meath and co. Westmeath were secure, and Fenianism appeared to be diminishing.

On leaving office Spencer was offered a marquessate by Gladstone, but after consulting Granville and Hartington refused it. He was now free to pursue his hobbies, rifle shooting and fox-hunting. In 1860 he was the chairman of a committee which met at Spencer House to form the National Rifle Association, and he was closely connected with that body until his death—as chairman 1867–8 and member of the council for almost fifty years. He frequently shot in the Lords' team in the Lords and Commons match, and presented the Spencer cup, to be competed for at the annual meeting by boys at public schools. Like his ancestors before him, he had been master of the Pytchley hounds (1861–4), and once more resumed in 1874. Spencer expended much time and effort in enhancing the hunt's reputation. One notable visitor to Northamptonshire was Elizabeth, empress of Austria, reputedly one of the most beautiful women in Europe. She was an excellent rider and enjoyed flouting convention, preferring beer to other drinks, and shocking guests at Althorp one night after dinner by smoking a cigar. She hunted with the Pytchley in March 1876 and again in 1878 and Spencer was subsequently invited to Gödöllö, the empress's favourite hunting seat in Hungary. The cost of being master was extremely heavy: in 1879, a year after he resigned the position, he had to seek a loan of £15,000 on account of the excess expenditure for the hounds.

Spencer also embarked on large-scale alterations to the house in the years 1876–8, including a new dining-room to house the collection of Reynolds paintings. In 1872 he had become lord lieutenant of Northamptonshire, and Spencer fully participated in the duties which holding this office entailed.

It was in the 1860s that Spencer first grew the large red beard which gave rise to his nickname, the Red Earl, a characteristic which cartoonists of the Irish press during his second viceroyalty were quick to exploit. In manhood he was a tall, commanding figure, some 6 feet 3 inches in height. His fortitude and stamina in the hunting field belied a basically weak constitution. Spencer was subject to sporadic illnesses, arising out of a weakness in one of his lungs, and he frequently visited German spas in search of better health.

To the outside world Spencer often appeared aloof and withdrawn. In 1904 Edmund Gosse, then librarian of the House of Lords, wrote down his impressions after meeting Spencer.

I found him very intimidating; one looks up in despair for his face at the top of a white cliff of his great beard. He was possibly shy, he certainly made me feel so, but he gives the impression of great dignity, and the temper of a very fine gentleman. I admire him intensely, but he is certainly the most alarming figure I have yet encountered here. (E. Gosse, diary, 14 March 1904, HL, MS L32)

Spencer's reserved manner in public stemmed mainly from a nervous disposition, but privately, when relaxed, his natural sense of fun was given full rein. He laid little claim to intellectual pursuits but was an industrious and conscientious administrator. His handwriting was exceptionally difficult to decipher, and in his speech-making his delivery lacked forcefulness. He accepted invitations to speak in public with reluctance and depended heavily upon notes. In religious matters he disliked extreme views; he was a patron of thirteen livings.

Spencer married Charlotte Frances Frederica Seymour (d. 1903), youngest of three daughters of Lady Augusta and Frederick Seymour, on 8 July 1858. All three sisters were noted beauties in London society. There was already a family link, as Adelaide, Spencer's stepmother, and Charlotte were cousins. Although from a Conservative background, she supported Spencer in his career and expressed herself trenchantly on political matters. Her private diaries contain memoranda on, for example, aspects of Fenianism and the Eastern question. There were no children of the marriage.

When Beaconsfield appointed the royal commission on agricultural depression in July 1879, chaired by the duke of Richmond, Spencer was the only Liberal peer out of the twenty members appointed, together with one Liberal commoner, G. J. Goschen. As a landowner of 27,185 acres, 16,800 of which were in Northamptonshire, with lesser holdings in Warwickshire, Hertfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Leicestershire, and Surrey, Spencer took a keen interest in the commission's deliberations. In November he was advised to recuperate from an illness, and, with rumours of a dissolution in the air, left for Algiers in December.

When Gladstone formed his second administration in 1880, Spencer joined the cabinet as lord president of the council with a seat in the cabinet. It was envisaged by Gladstone that Spencer would be able to advise on Irish matters as well as carry out the duties of lord president. The post carried formal responsibility for supervision of the education department, but in practice the vice-president was in charge of its day-to-day running.

One of the first tasks of the new government was to complete the existing legislation relating to compulsory education. The 1870 Education Act had allowed school boards to have ambiguous permissive powers on compulsion: the 1876 act created school attendance committees, which were able to make by-laws for the enforcement of attendance. Spencer calculated that in 1880 about a quarter of the population were still outside the influence of the by-laws. Spencer, A. J. Mundella, the vice-president, and W. E. Forster, vice-president in Gladstone's first government, discussed and approved a new bill. By August 1880 an act establishing attendance was on the statute book and was an immediate success.

Another major educational reform with which Spencer is associated is the new code of 1882. This was the first major reconstruction of the grant award system to schools since Robert Lowe, then vice-president, had introduced the notorious ‘payment by results’ system some twenty years previously. Besides altering the basis for payment, the code encouraged a wider curriculum and more intelligent teaching in elementary schools; it also gave an impetus to the development of higher grade schools which enabled older and more advanced elementary pupils to continue their education. An important series of royal commissions was instigated, which investigated medical and technical education, and the provision of secondary and higher education in Wales.

While carrying out these duties, Spencer was at the same time heavily involved in advising on Irish affairs. W. E. Forster, the chief secretary, advocated strong measures to repress the Land League, especially the suspension of habeas corpus, and was supported in this view by the viceroy, Lord Cowper. Early in 1881 a Coercion Bill and a Peace Preservation Bill were steered through the Commons by Forster, though Gladstone's Land Bill, aimed at pacifying the Irish nationalists, became law in August. Parnell's defiance led to his arrest on 12 October. Secret negotiations with Chamberlain as intermediary led to Parnell's release on 1 May. The following day, Forster resigned. On 3 May Spencer replaced Cowper as lord lieutenant while retaining his post as lord president of the council.

Spencer was not unprepared for his return to Ireland. At Gladstone's request he had made two visits, in October and December 1881, to discuss matters with Cowper and Forster and to report back on the situation. After crossing to Ireland on 5 May with the new chief secretary, Frederick Cavendish, Hartington's younger brother, Spencer made his official entry into Dublin the following day. He attended a meeting at the castle in the afternoon with Cavendish and T. H. Burke, the under-secretary. Walking back across Phoenix Park later, Cavendish and Burke were brutally murdered by members of the Invincibles, a secret organization whose purpose was to assassinate British officials in Ireland. Spencer, who had left the castle on horseback and was in the viceregal lodge when the murders took place, told Gladstone, ‘I must have crossed the road riding either behind or in front of them within a minute of them’ (BL, Add. MS 44308, fol. 217).

The news of the assassinations was received in England with a mixture of shock and fury. A Prevention of Crime Bill, already sanctioned in principle by the cabinet, received the royal assent on 12 July and was rigorously enforced. For the next three years, near siege conditions prevailed at the castle. Spencer was everywhere accompanied by a detective, and on subsequent tours of Ireland the cavalcade included eight hussars and eight mounted police at the front, while behind were two armed constables in a car followed by two more detectives.

The Irish crisis dramatically and unexpectedly thrust Spencer into the limelight. His wishes were met whenever possible and his handling of the new situation was widely admired. Gladstone told the queen on 27 May, ‘He possesses all the fine and genuine qualities of his excellent Uncle Althorp, and exercises them with heightened powers’. Within a few days of the assassinations, there was a complete turnabout in the real power of Irish administration. G. O. Trevelyan was appointed as Irish chief secretary. The previous holder, Forster, had been the main spokesman for Irish affairs in the cabinet and in the Commons. His lord lieutenant, Cowper, was outside the cabinet and played a subordinate role in Irish affairs. Now the positions were reversed.

Two immediate tasks faced Spencer: the reorganization of the police forces and the destruction of secret societies responsible for political murders. The Royal Irish Constabulary and the Dublin Metropolitan Police were inadequate for the range of duties required of them and new leadership was found. Spencer also secured permission from Gladstone to appoint an under-secretary for police and crime, responsible for creating a secret intelligence section to monitor potential terrorists and to infiltrate their ranks. The reform of the magistracy was also undertaken. By the end of the year, the situation in Ireland was relatively quiet largely because of Spencer's prompt action.

One law case which was to cause great controversy followed the murder of the Joyce family at Maamtrasna, Galway, earlier in the year. Ten men were accused of the crime: two of these turned informers, five were given a late reprieve, but one of them, Myles Joyce, declared his innocence throughout the trial. He was hanged in December and came to be regarded as a political martyr. Spencer admitted to Harcourt after the executions had been carried out that ‘the Maamtrasna decision worried me dreadfully up to the last’ (MS Harcourt 40).

From early in 1883 Spencer once more began to attend cabinet meetings in London, where matters concerning Ireland were on the agenda, and in March he readily agreed to relinquish the lord presidency to Carlingford. Spencer was able to make tours of Ireland, partly for recreation and partly to gather information on the state of the country at first hand. His views on methods of dealing with the distress of Irish tenants were not sentimental. He strongly favoured the workhouse system and supported the view that the government should help unions in cases where people wished to emigrate.

In July 1884 Spencer let it be known that he was willing to be considered for the post of viceroy of India, as the incumbent, Ripon, was contemplating giving it up. However, Trevelyan, after two years as chief secretary, urgently requested to be relieved of his position and Spencer was involved in finding a suitable successor. Campbell-Bannerman replaced Trevelyan in October, and Spencer continued as lord lieutenant.

In outlining a plan of desired legislation to Gladstone in January 1885, Spencer stated that the most urgent matter was the renewal of the Crimes Act, due to expire at the end of the session. One of Spencer's cherished hopes was for the prince and princess of Wales to visit Ireland, and he was closely involved in the delicate negotiations with the queen. The visit, which took place between 8 and 27 April, with the Spencers accompanying their visitors, was a success in the loyal north, though the party ran into trouble in the south. Spencer was now emboldened to raise with the queen the issue of a royal residence in Ireland, but this was instantly rejected. ‘I feel inclined’, Spencer gloomily told Ponsonby in May, ‘to throw up the sponge and retire to my plough in Northamptonshire.’

The crises in the cabinet engendered by the Egyptian question and the fall of Khartoum, with differences on policy within the cabinet, raised doubts on the survival of the government. Spencer's programme of legislation for Ireland, the renewal of the Crimes Act and a Land Purchase Bill, was not discussed in cabinet until the end of April. The search for a solution to the Irish problem brought Spencer into sharp conflict with Chamberlain and Dilke, who demanded in place of the Land Bill a large measure of local government. While these matters were awaiting settlement, Gladstone was defeated on the budget in the early hours of 9 June and the government resigned.

However, Spencer's troubles were not quite over. On 17 July Parnell's motion censuring Spencer for the administration of law and order in Ireland, especially the handling of the Maamtrasna murders case, was strongly supported by Randolph Churchill and others. While in opposition, the Conservatives had supported Spencer's firm line on the case. Members from both parties were highly critical of this attack, and within a week a banquet in honour of Spencer, attended by more than 200 Liberals from both houses, under the chairmanship of Hartington, was held at Westminster Palace Hotel.

Commenting on Gladstone's address to his Midlothian constituents, issued on 17 September 1885, Spencer told a friend:

Suppose we could 1. Get security for the landlords 2. Prevent a civil war with Ulster 3. Make the Irish nation our friends, not enemies, it would be worth while giving them Home Rule, but I don't see my way to the three conditions or any of them being secured. (Spencer to C. Boyle, 20 Sept 1885, Althorp MSS)

Spencer was closely involved with the autumn consultations on Ireland. After meeting Hartington at Chatsworth on 5 December, he joined Rosebery at Hawarden on 8 December, where they talked at length with Gladstone. This was followed by meetings with Goschen and Northbrook. Spencer also sounded out a number of Irish landlords on Gladstone's behalf. On the last day of the year, he wrote to Mundella:‘I must confess to you that I look on the old methods of dealing with Ireland … as gone and hopeless. … There seems nothing but a big measure, Home Rule with proper safeguards, or at no distant day, coercion stronger than we have ever had before. The latter cannot be thought of now’ (Mundella MSS, MP 6P/18).

Following Gladstone's adoption of the policy of home rule, he sketched out with his two most trusted colleagues, Spencer and Granville, the strategies to be pursued if they were returned to office. After the Salisbury government's defeat in the Commons on 27 January 1886, Spencer was much occupied in advising Gladstone on candidates for office in the new ministry, a difficult task in view of the secession of so many moderate Liberals in both houses of parliament. He had hoped to have been offered the Admiralty but, because of difficulties over Granville, reluctantly resumed his former post of lord president of the council. His main task, however, was to help in the preparation of Irish legislation.

Two bills were submitted to the cabinet: one proposing a new Irish legislature, the other dealing with land purchase on a large scale. Chamberlain and Trevelyan thereupon resigned. The Government of Ireland Bill was presented to the Commons on 8 April by Gladstone, and the Land Purchase Bill eight days later. The vital debate on the second reading of the Government of Ireland Bill in May extended over fourteen nights, and encountered opposition from Irish Unionists and a strong minority of Liberals; the scheme for land purchase, unpopular with Irish landowners, also weighed against the success of the Home Rule Bill. On 7 June the government was defeated by 341 to 311, with 93 Liberals voting with the Conservatives. Defeated at the subsequent general election, Gladstone resigned on 20 July.

Politics were not the only worry for Spencer at this time. His two spells as lord lieutenant of Ireland had been a heavy financial drain. The depressed state of agriculture throughout the country affected the Althorp estate, with agricultural prices unprecedentedly low. By late 1885 Spencer calculated that his net income was 40 per cent less than it had been ten years previously.

Perhaps the most painful consequence of Spencer's acceptance of home rule was the social ostracism and hurtful public criticism which long dogged him. Edward Hamilton, Gladstone's former secretary, noted that ‘his [Spencer's] friends actually cut him and won't meet him’; these sentiments were shared by the queen, who pointedly no longer invited Spencer, as a leading member of the opposition, to Windsor.

Spencer closely followed events in Ireland and the attempts of the Salisbury government to control them. Greater demands were being made on politicians for public speeches, and at great cost to himself Spencer accepted many invitations to address rallies. He caused unintentional consternation in the Liberal camp by stating during a speech at Stockton in October 1889 that Irish members should be retained in an imperial parliament. Earlier in the year, Spencer had been in the public eye when he had shaken hands with Parnell at a dinner given by Liberals. In December 1891 Althorp was the setting for a meeting between the Liberal leaders, Gladstone, Harcourt, Morley, Rosebery, and Spencer, to discuss aspects of the Newcastle programme, announced in October, which dealt with future Liberal policy.

Spencer continued to participate in Northamptonshire affairs. With the establishment of county councils following the 1888 Local Government Act, Spencer became first chairman of the Northamptonshire county council, efficiently and conscientiously carrying out his duties. When the Liberals were returned to power in August 1892 it was obvious that he could not carry a double burden, and he relinquished this post at the end of the year. However, he continued to take a close interest in county council affairs and retained his councillorship until 1907.

With little prospect of improvement in rent and land values, Spencer was obliged to seek a dramatic solution to his financial problems. The Althorp Library, long acknowledged as one of the great European collections, had been mainly amassed by his grandfather, George John, second Earl Spencer. It included many fifteenth- and sixteenth-century volumes, among them the Gutenberg Bible, the first Mainz psalter, and fifty-three Caxtons. The purchase, for £210,000, was made by Mrs Enriqueta Rylands, widow of John Rylands, the Manchester millionaire, who wished to found a theological library in that city in memory of her husband. In August and September 1892, 600 cases of books were packed and dispatched to Manchester. In October 1899, when the John Rylands Library was opened, Spencer, as chancellor of the Victoria University (1892–1907), was awarded an honorary degree by the library's benefactress.

After the general election of 1892, in which the Liberals were returned with a small majority, Spencer was delighted to be appointed to the post of first lord of the Admiralty. He assumed office at a time when there was widespread concern over the expansion by other European powers of their navies: Britain's long undisputed supremacy was now being challenged, particularly by France and Russia. The large shipbuilding programme embodied in the Naval Defence Act of 1889 had already begun, and continuity of administration was of prime importance. Spencer was the first to set the precedent of retaining in office the professional members of the board who had been appointed by his predecessor.

Spencer handled the administrative and political aspects of his post with great skill. An early set-back while the Spencer programme was being discussed occurred in 1893 when the Victoria, the flagship of Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon, was rammed by another battleship, the Camperdown, with the loss of more than 350 officers and men. Spencer came into conflict with Harcourt, the chancellor of the exchequer, over his demands, backed by the sea lords, for seven more first-class battleships, six cruisers, and thirty-six destroyers. In December 1893 Lord George Hamilton, Spencer's predecessor, moved in the Commons for immediate action to increase the size of the navy. Harcourt informed the house that the sea lords were satisfied with the present expenditure. This led the following day to the admirals entirely repudiating this interpretation. On 6 January 1894 Gladstone sent for Spencer and told him that he could not accept the estimates and would resign rather than do so. Spencer, for his part, refused to yield further. Gladstone resigned from office on 1 March and a week later the cabinet, under Rosebery, formally approved the estimates.

It may seem surprising, in the light of fundamental disagreements on naval policy, that Gladstone was prepared to nominate Spencer as his successor. On 2 March, as he was setting out for Windsor, he confided in John Morley that if invited by the queen to advise on his successor, he would nominate Spencer. However, at the subsequent interview Gladstone's advice was not sought, and the queen chose Rosebery. Spencer was happy to serve under the new prime minister until the government fell in June 1895. In preparing the naval estimates for his last year in office, Spencer was able to state that the shipbuilding programme far outstripped those of France and Russia.

Freed from the responsibilities of office, Spencer resumed hunting with the Pytchley, having taken over the mastership for the third time in 1890. Always a keen and progressive farmer, he was president of the Royal Agricultural Society in 1898.

The outbreak of the South African War in 1899 deepened the divisions within the Liberal Party, a group of leading members, known as Liberal Imperialists, having been formed under Rosebery's leadership. Spencer supported Campbell-Bannerman, the opposition leader in the Commons, who adopted a central position over the war. During Kimberley's illness in 1901 Spencer acted as leader of the opposition in the Lords, and was elected leader in April 1902. He spearheaded the attack on the Education Bill in the Lords but without success. The death of Lady Spencer on 31 October 1903 was a severe blow. In the following year, on 23 September, Spencer suffered a heart attack and was advised to rest for the remainder of the year.

This did not dispel rumours of the probability of Spencer's appointment to the highest office. Salisbury had resigned in July 1902 and his nephew, Balfour, presided over a party divided by the free-trade controversy. A return of the Liberals to power seemed likely. Much speculation was aroused by the appearance in the press on 10 February 1905 of a letter, the day after Spencer had presided at a conference of Liberal leaders, stating his views on the policy of a future Liberal government. Spencer protested in vain at the interpretation placed on the letter by both the politicians and public. The Times's reaction was that, in the event of a Liberal victory, Spencer would be offered the premiership (11 Feb 1905).

Spencer returned to London from Marienbad on 18 September in great spirits, and at the end of the month he was at the family's property at North Creake, Norfolk, for shooting. On 11 October he suffered a severe stroke which removed him from the political scene. ‘Poor Lord Spencer’, wrote the young Winston Churchill to Rosebery, ‘it was rather like a ship sinking in sight of land’ (19 Oct 1903, Rosebery MSS, 10009, fol. 171). He retained a keen interest in naval and political developments, and was delighted at the appointment of Campbell-Bannerman as prime minister in December 1905 and at the impressive general election victory of the Liberals in January 1906, when they gained 226 seats.

Spencer resigned from the chancellorship of Manchester University and the lord lieutenancy of Northamptonshire in 1908. Now in failing health, he attended the Garter ceremony at Windsor in November 1909. On 5 July 1910 Spencer suffered a further stroke and died on 13 August at Althorp. He was buried beside his wife at Great Brington, Northamptonshire, on 18 August. His half-brother, Robert, succeeded him as sixth earl.

Spencer's prominent role in Liberal politics over a period of almost four decades has not received the recognition it deserves. First coming to prominence in 1867 over franchise reform, he was a member of successive Liberal governments for the rest of the century, and a member of the cabinet in all except the first. As lord lieutenant of Ireland during the crucial periods 1868–74 and 1882–5, Spencer was given the difficult task of carrying out the provisions of the Land Acts and a Coercion Act. Spencer's stubborn opposition to Chamberlain's central board scheme was crucial in the cabinet's rejection of it in May 1885.

His subsequent conversion to the cause of Irish home rule was regarded with astonishment by members of both parties. In fact, Spencer's decision was entirely consistent with his character: once convinced of the necessity of a course of action, he was willing to pursue it, however uncomfortable the consequences. Another example was the support given to the admirals in 1893 for the navy estimates, in spite of Gladstone's protests. Spencer rarely courted popularity for its own sake, but he treated political opponents with courtesy. Loyalty was another quality which he prized highly. It seems unlikely that Gladstone could have successfully formed a government in 1886 without Spencer's assistance, and his support for home rule remained critical, as Gladstone made it a test of loyalty to Liberalism.

Two other areas of Spencer's activities are worthy of note. His shipbuilding programme and steps taken to improve naval defences were of immense value when the First World War broke out; and, as lord president, he promoted compulsory attendance through the 1880 Education Bill and the drawing up of more enlightened codes, which affected the status and work of inspectors, teachers, and children, and encouraged the development of a national system of schools and higher education for Wales.

The likelihood of a Spencer ministry in 1903 and 1904 if Balfour had resigned was widely accepted at the time. Although he inspired few with his oratory, he possessed many of the qualities needed for a prime minister. Reflecting on the merits of rival contenders, Harcourt, Rosebery, and Spencer, for the post in July 1894, Gladstone chose Spencer:

Less brilliant than either, he has far more experience … he has also decidedly more of that very important quality termed weight, and his cast of character I think affords more guarantees of the moderation he would combine with zeal, and more possibility of forecasting the course he would pursue. (W. E. Gladstone, memorandum, 25 July 1894, BL, Add. MS 44790, fols. 145–6)

Spencer's reserved manner was sometimes mistaken for aloofness. He told his wife in 1892, ‘Granville once said that no one who had been Viceroy altogether lost its effect on his manners. I always kept that before me, and tried to be natural, but there may be something in it’ (6 June 1892, Althorp MSS). Though he never gained the highest office, Spencer was content to have served his party with a loyalty which both friends and foes alike acknowledged. His achievements were many, and, like a true whig, without being a leader of popular movements he worked for changes through constitutional means which would ultimately benefit the country.

Peter Gordon DNB