"Ian MacInnes"

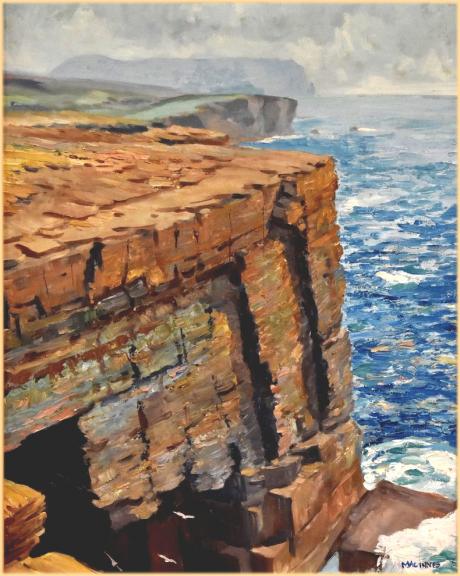

Yesnaby is an area in Sandwick, on the west coast of Orkney Mainland, Scotland, south of Skara Brae. It is renowned for its spectacular Old Red Sandstone coastal cliff scenery which includes sea stacks, blowholes, geos and frequently boiling seas. A car park, coastal trail and interpretive panels serve visitors. The area is popular with climbers because of Yesnaby Castle, a two-legged sea stack just south of the Brough of Bigging. The stack is sometimes described as a smaller version of the Old Man of Hoy.[citation needed] Yesnaby is also one of the very few places where Primula scotica grows.The coastal cliffs are formed from the Lower Devonian sandstones ascribed to the Yesnaby Sandstone Group - a set of geological formations restricted to the Yesnaby area, and to the overlying beds of the Lower Stromness Flagstones. Fossil stromatolites from 390-400 million years ago can be found in the cliffs in the latter. They are locally known as Horse Tooth Stones from a supposed resemblance. Orkney folklore has it that a woman known as the "Yesnaby Healer" had the ability to stop bleeding in any person, even over a distance. The Orkney composer Peter Maxwell Davies has immortalised Yesnaby through "Yesnaby Ground", an Interlude for solo piano.

The cliffs are truly spectacular, encompassing some of the finest coastal scenery you will ever see.Along the way are blowholes, geos (narrow sea inlets), striking sea stacks, and the remains of prehistoric settlements. The path is easy to follow and the going is not difficult. There are several interpretive signs to explain the geology and plant life along the cliffs. One of the best walks on Orkney, and well worth the outing.

During WWI and WWII a large number of coastal defence stations were built along the cliffs of Orkney. Most were armed with anti-aircraft guns and with searchlight towers to pick out enemy aircraft. The cliffs at Yesnaby were one such site. The station was manned by Royal Navy personnel. The brick buildings are starkly functional, nothing more than rectangular structures with stone lintels for doors and windows. One of the surviving buildings housed diesel engines used to provide electricity, and another housed a generator. An observation hut has also survived.

The geology along the coast at Yesnaby is truly fascinating, with evidence of volcanic activity and sand rippling, sand cracking, and pseudomorphs over 300 million years ago. The cliffs are formed from Lower Devonian Sandstone topped by Lower Stromness Flagstones, where you can often find fossilised stromatolites.

Orkney also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of Great Britain. Orkney is 16 kilometres (10 mi) north of the coast of Caithness and comprises approximately 70 islands, of which 20 are inhabited. The largest island, Mainland, is often referred to as "the Mainland". It has an area of 523 square kilometres (202 sq mi), making it the sixth-largest Scottish island and the tenth-largest island in the British Isles. The largest settlement and administrative centre is Kirkwall.

A form of the name dates to the pre-Roman era and the islands have been inhabited for at least 8500 years, originally occupied by Mesolithic and Neolithic tribes and then by the Picts. Orkney was invaded and forcibly annexed by Norway in 875 and settled by the Norse. The Scottish Parliament then re-annexed the earldom to the Scottish Crown in 1472, following the failed payment of a dowry for James III's bride Margaret of Denmark. Orkney contains some of the oldest and best-preserved Neolithic sites in Europe, and the "Heart of Neolithic Orkney" is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Orkney is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, a constituency of the Scottish Parliament, a lieutenancy area, and a historic county. The local council is Orkney Islands Council, one of only three Councils in Scotland with a majority of elected members who are independents.

In addition to the Mainland, most of the islands are in two groups, the North and South Isles, all of which have an underlying geological base of Old Red Sandstone. The climate is mild and the soils are extremely fertile, most of the land being farmed. Agriculture is the most important sector of the economy. The significant wind and marine energy resources are of growing importance, and the island generates more than its total yearly electricity demand using renewables. The local people are known as Orcadians and have a distinctive dialect of Insular Scots and a rich inheritance of folklore. There is an abundance of marine and avian wildlife.

Pytheas of Massilia visited Britain – probably sometime between 322 and 285 BCE – and described it as triangular in shape, with a northern tip called Orcas. This may have referred to Dunnet Head, from which Orkney is visible. Writing in the 1st century AD, the Roman geographer Pomponius Mela called the islands Orcades, as did Tacitus in 98 AD, claiming that his father-in-law Agricola had "discovered and subjugated the Orcades hitherto unknown" (although both Mela and Pliny had previously referred to the islands. Etymologists usually interpret the element orc- as a Pictish tribal name meaning "young pig" or "young boar". Speakers of Old Irish referred to the islands as Insi Orc "island of the pigs". The archipelago is known as Ynysoedd Erch in modern Welsh and Arcaibh in modern Scottish Gaelic, the -aibh representing a fossilized prepositional case ending.

The Anglo-Saxon monk Bede refers to the islands as Orcades insulae in his seminal work Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

Norwegian settlers arriving from the late ninth century reinterpreted orc as the Old Norse orkn "seal" and added eyjar "islands" to the end so the name became Orkneyjar "Seal Islands". The plural suffix -jar was later removed in English leaving the modern name "Orkney". According to the Historia Norwegiæ, Orkney was named after an earl called Orkan.

The Norse knew Mainland Orkney as Megenland "Mainland" or as Hrossey "Horse Island". The island is sometimes referred to as Pomona (or Pomonia), a name that stems from a sixteenth-century mistranslation by George Buchanan, which has rarely been used locally.

A charred hazelnut shell, recovered in 2007 during excavations in Tankerness on the Mainland has been dated to 6820–6660 BC indicating the presence of Mesolithic nomadic tribes. The earliest known permanent settlement is at Knap of Howar, a Neolithic farmstead on the island of Papa Westray, which dates from 3500 BC. The village of Skara Brae, Europe's best-preserved Neolithic settlement, is believed to have been inhabited from around 3100 BC. Other remains from that era include the Standing Stones of Stenness, the Maeshowe passage grave, the Ring of Brodgar and other standing stones. Many of the Neolithic settlements were abandoned around 2500 BC, possibly due to changes in the climate.

During the Bronze Age fewer large stone structures were built although the great ceremonial circles continued in use as metalworking was slowly introduced to Britain from Europe over a lengthy period.[29][30] There are relatively few Orcadian sites dating from this era although there is the impressive Plumcake Mound near the Ring of Brodgar and various islands sites such as Tofts Ness on Sanday and the remains of two houses on Holm of Faray.

Excavations at Quanterness on the Mainland have revealed an Atlantic roundhouse built about 700 BC and similar finds have been made at Bu on the Mainland and Pierowall Quarry on Westray. The most impressive Iron Age structures of Orkney are the ruins of later round towers called "brochs" and their associated settlements such as the Broch of Burroughston[34] and Broch of Gurness. The nature and origin of these buildings is a subject of ongoing debate. Other structures from this period include underground storehouses, and aisled roundhouses, the latter usually in association with earlier broch sites.

During the Roman invasion of Britain the "King of Orkney" was one of 11 British leaders who is said to have submitted to the Emperor Claudius in AD 43 at Colchester. After the Agricolan fleet had come and gone, possibly anchoring at Shapinsay, direct Roman influence seems to have been limited to trade rather than conquest.

By the late Iron Age, Orkney was part of the Pictish kingdom, and although the archaeological remains from this period are less impressive there is every reason to suppose the fertile soils and rich seas of Orkney provided the Picts with a comfortable living. The Dalriadic Gaels began to influence the islands towards the close of the Pictish era, perhaps principally through the role of Celtic missionaries, as evidenced by several islands bearing the epithet "Papa" in commemoration of these preachers. However, before the Gaelic presence could establish itself the Picts were gradually dispossessed by the Norsemen from the late 8th century onwards. The nature of this transition is controversial, and theories range from peaceful integration to enslavement and genocide. It has been suggested that an assault by forces from Fortriu in 681 in which Orkney was "annihilated" may have led to a weakening of the local power base and helped the Norse come to prominence.

Both Orkney and Shetland saw a significant influx of Norwegian settlers during the late 8th and early 9th centuries. Vikings made the islands the headquarters of their pirate expeditions carried out against Norway and the coasts of mainland Scotland. In response, Norwegian king Harald Fairhair (Harald Hårfagre) annexed the Northern Isles, comprising Orkney and Shetland, in 875. (It is clear that this story, which appears in the Orkneyinga Saga, is based on the later voyages of Magnus Barelegs and some scholars believe it to be apocryphal.)[45] Rognvald Eysteinsson received Orkney and Shetland from Harald as an earldom as reparation for the death of his son in battle in Scotland, and then passed the earldom on to his brother Sigurd the Mighty.

However, Sigurd's line barely survived him and it was Torf-Einarr, Rognvald's son by a slave, who founded a dynasty that controlled the islands for centuries after his death.He was succeeded by his son Thorfinn Skull-splitter and during this time the deposed Norwegian King Eric Bloodaxe often used Orkney as a raiding base before being killed in 954. Thorfinn's death and presumed burial at the broch of Hoxa, on South Ronaldsay, led to a long period of dynastic strife.

A group of warriors in medieval garb surround two men whose postures suggest they are about to embrace. The man on the right is taller, has long fair hair and wears a bright red tunic. The man on the left his balding with short grey hair and a white beard. He wears a long brown cloak.

Artist's conception of King Olaf Tryggvason of Norway, who forcibly Christianised Orkney. Painting by Peter Nicolai Arbo.

Initially a pagan culture, detailed information about the turn to the Christian religion to the islands of Scotland during the Norse-era is elusive. The Orkneyinga Saga suggests the islands were Christianised by Olaf Tryggvasson in 995 when he stopped at South Walls on his way from Ireland to Norway. The King summoned the jarl Sigurd the Stout and said, "I order you and all your subjects to be baptised. If you refuse, I'll have you killed on the spot and I swear I will ravage every island with fire and steel." Unsurprisingly, Sigurd agreed and the islands became Christian at a stroke, receiving their own bishop in the early 11th century.

Thorfinn the Mighty was a son of Sigurd and a grandson of King Máel Coluim mac Cináeda (Malcolm II of Scotland). Along with Sigurd's other sons he ruled Orkney during the first half of the 11th century and extended his authority over a small maritime empire stretching from Dublin to Shetland. Thorfinn died around 1065 and his sons Paul and Erlend succeeded him, fighting at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. Paul and Erlend quarreled as adults and this dispute carried on to the next generation. The martyrdom of Magnus Erlendsson, who was killed in April 1116 by his cousin Haakon Paulsson, resulted in the building of St. Magnus Cathedral, still today a dominating feature of Kirkwall.

Unusually, from c. 1100 onwards the Norse jarls owed allegiance both to Norway for Orkney and to the Scottish crown through their holdings as Earls of Caithness. In 1231 the line of Norse earls, unbroken since Rognvald, ended with Jon Haraldsson's murder in Thurso. The Earldom of Caithness was granted to Magnus, second son of the Earl of Angus, whom Haakon IV of Norway confirmed as Earl of Orkney in 1236.In 1290, the death of the child princess Margaret, Maid of Norway in Orkney, en route to mainland Scotland, created a disputed succession that led to the Wars of Scottish Independence. In 1379 the earldom passed to the Sinclair family, who were also barons of Roslin near Edinburgh.

Evidence of the Viking presence is widespread, and includes the settlement at the Brough of Birsay,[67] the vast majority of place names,and the runic inscriptions at Maeshowe.

A picture on a page in an old book. A man at left wears tights and a tunic with a lion rampant design and holds a sword and scepter. A woman at right wears a dress with an heraldic design bordered with ermine and carries a thistle in one hand and a scepter in the other. They stand on a green surface over a legend in Scots that begins "James the Thrid of Nobil Memorie..." (sic) and notes that he "marrit the King of Denmark's dochter."

In 1468 Orkney was pledged by Christian I, in his capacity as King of Norway, as security against the payment of the dowry of his daughter Margaret, betrothed to James III of Scotland. However the money was never paid, and Orkney was annexed by the Kingdom of Scotland in 1472.

The history of Orkney prior to this time is largely the history of the ruling aristocracy. From now on the ordinary people emerge with greater clarity. An influx of Scottish entrepreneurs helped to create a diverse and independent community that included farmers, fishermen and merchants that called themselves comunitas Orcadie and who proved themselves increasingly able to defend their rights against their feudal overlords.

From at least the 16th century, boats from mainland Scotland and the Netherlands dominated the local herring fishery. There is little evidence of an Orcadian fleet until the 19th century but it grew rapidly and 700 boats were involved by the 1840s with Stronsay and later Stromness becoming leading centres of development. White fish never became as dominant as in other Scottish ports.

In the 17th century, Orcadians formed the overwhelming majority of employees of the Hudson's Bay Company in Canada. The harsh climate of Orkney and the Orcadian reputation for sobriety and their boat handling skills made them ideal candidates for the rigours of the Canadian north. During this period, burning kelp briefly became a mainstay of the islands' economy. For example on Shapinsay over 3,000 long tons (3,048 t) of burned seaweed were produced per annum to make soda ash, bringing in £20,000 to the local economy. The industry collapsed suddenly in 1830 after the removal of tariffs on imported alkali.

Agricultural improvements beginning in the 17th century resulted in the enclosure of the commons and ultimately in the Victoria era the emergence of large and well-managed farms using a five-shift rotation system and producing high-quality beef cattle.

During the 18th century Jacobite risings, Orkney was largely Jacobite in its sympathies. At the end of the 1715 rebellion, a large number of Jacobites who had fled north from mainland Scotland sought refuge on Orkney and were helped on to safety in Sweden. In 1745, the Jacobite lairds on the islands ensured that Orkney remained pro-Jacobite in outlook, and was a safe place to land supplies from Spain to aid their cause. Orkney was the last place in the British Isles that held out for the Jacobites and was not retaken by the British Government until 24 May 1746, over a month after the defeat of the main Jacobite army at Culloden.

The Italian Chapel on Lamb Holm was built and decorated by Italian prisoners of war working on the Churchill Barriers.

Orkney was the site of a Royal Navy base at Scapa Flow, which played a major role in World War I and II. After the Armistice in 1918, the German High Seas Fleet was transferred in its entirety to Scapa Flow to await a decision on its future. The German sailors opened the sea-cocks and scuttled all the ships. Most ships were salvaged, but the remaining wrecks are now a favoured haunt of recreational divers. One month into World War II, a German U-boat sank the Royal Navy battleship HMS Royal Oak in Scapa Flow. As a result, barriers were built to close most of the access channels; these had the additional advantage of creating causeways enabling travellers to go from island to island by road instead of being obliged to rely on ferries. The causeways were constructed by Italian prisoners of war, who also constructed the ornate Italian Chapel.

The navy base became run down after the war, eventually closing in 1957. The problem of a declining population was significant in the post-war years, though in the last decades of the 20th century there was a recovery and life in Orkney focused on growing prosperity and the emergence of a relatively classless society. Orkney was rated as the best place to live in Scotland in both 2013 and 2014 according to the Halifax Quality of Life survey.

IAN MacInnes, one of nine children, was educated at Stromness Academy, where he was in the same class as George Mackay Brown, who became a close friend. Neither boy cared much for lessons, but both loved Stromness - the characters, the stories, the secrets and the scandals that make up a small community. What George celebrated in writing, Ian celebrated in paint. The Orcadian artist and teacher Ian MacInnes was the friend and illustrator, from his first book, of the poet George Mackay Brown.

They met at Stromness Academy, where they were in the same infant class, and the two struck up a friendship which was to last until the poet's death 70 years later. They shared an intense love of their town and its people, especially the characters who were to be found in Stromness's winding streets ("uncoiling like a sailor's rope", as Brown put it), and around its piers and slipways.

Both boys showed high artistic promise. George impressed his teachers at an early age by the quality of his story-telling, while Ian launched his artistic career when still at school with a series of brilliant caricatures of local worthies, published weekly in The Orkney Herald, which provoked much mirth and some mortification. Ian MacInnes designed and illustrated George Mackay Brown's first collection of verse, The Storm and Other Poems (1954), and went on to design the dust-jackets of some of his finest novels, including Greenvoe (1972) and Magnus (1975). He also illustrated Brown's three children's books The Two Fiddlers (1974), Pictures in the Cave (1977) and Six Lives of Fankle the Cat (1980).

The township of Rackwick nestles under the great western cliffs of Hoy, the "high island" to the south of Stromness. This "hidden valley of light", as Brown described it in a poem dedicated to MacInnes, gave an extra stimulus to both poet and painter and was to inspire some of their finest work. Summer after summer MacInnes brought home a succession of magnificent glowing studies of sea and cliff and derelict croft, while Brown composed what many still regard as his masterpiece, Fishermen with Ploughs (1971).

Then in 1970 Peter Maxwell Davies came to Rackwick in search of silence and fresh creative inspiration. The valley cast its spell, and the composer put down his roots. New and enduring friendships were quickly established; and the music flowed in abundance. The full significance of Rackwick in the rich flowering of Orcadian culture in the late 20th century has still to be properly evaluated, but its importance is beyond question.

He enrolled at Gray's School of Art in Aberdeen on a course that (by a nice irony) was soon to be interrupted by several years' war service as a chief petty officer in the Navy. After the Second World War he completed his art course (collecting a prestigious medal on the way).

His lifelong commitment to socialism was learned early, in Peter Esson’s tailor shop. The crusading Communist George Robertson, a provost of Stromness, was another strong influence on him. It was a practical socialism, founded on a belief in the power of co-operation. Ian MacInnes's first choice of career was the sea. His father had been an officer in the lighthouse ship Pole Star and his eldest brother was well on the way to becoming a master mariner. But Ian's eyesight denied him that opportunity.

It was already clear that he was a promising artist; as a schoolboy, his series of cartoons of local worthies, published in the Orkney Herald, were admired for their facility and mischievous satirical edge. He enrolled at Grays School of Art in 1939, but war interrupted his studies: he joined up in 1941, when the Soviet Union was invaded, and became a chief petty officer in Lowestoft, later travelling on troop ships as far as Australia.

He resumed his studies after the war in an atmosphere of optimism and hope, Labour having been swept to power by a landslide. On a personal level, Ian carried off the George Arthur Davidson Medal for Art and held his first exhibition in Orkney. He met his future wife, Jean Barclay, a war widow, at Harriet’s Bar in Aberdeen - he saw her striking profile across a crowded room; his painting of her in a New Look black suit captures her, and his feeling for her, perfectly. In 1949, they married and settled in Orkney with Jean’s daughter, Sheena. Ian became one of the first itinerant art teachers in the county and a leading light in local politics. As a councillor, he was never afraid to back the underdog or engage in the thorniest of issues. It was at this time that he was instrumental in starting the Orkney Fisherman’s Society, a co-operative designed to support and protect local workers.

War had left him with a hatred of violence and a contempt for the hierarchies of power. He joined the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, addressed meetings and organised protest marches, learning quickly that he was a powerful speaker who could mobilise others into action. Perhaps his most successful campaign was against Rio Tinto Zinc, which wanted to mine for uranium between Stromness and Yesnaby, on the cliffs which he loved and painted on so often. Orcadians will remember the slogan that met visitors to the town: "Keep Orkney Green and Attractive, Not Black and Radioactive". Ian also contested the poll tax, challenging its legality in court and carrying out his own defence. He subscribed to the Morning Star, ordering multiple copies to make it worthwhile for the newsagent to carry the paper.

In 1964, he stood as Labour candidate in Orkney and Shetland against the Liberal Party’s Jo Grimond, bringing to a hopeless task the same passion and energy that informed all aspects of his life. Later, he thought the Labour Party had moved to the right, and the last straw for him was when the radical MP Norman Buchan was passed over for a post in the shadow cabinet by Neil Kinnock; Ian tore up his membership card. Latterly, he was a supporter of the Scottish Socialist Party. Meanwhile, his teaching career flourished - he was energetic and engaging in the classroom, and many Orkney artists owe him a debt. He was a thorn in the flesh of authority here, too, supporting the rights of the underprivileged, and working to protect teachers’ pay and conditions. When it became clear that his diploma in art wasn’t considered academic enough to allow him to apply for promotion, he enrolled as one of the first batch of Open University students, graduated and was appointed headmaster of Stromness Academy in 1979. Here, as in all other areas of his life, he put into practice the ideals he believed in - social inclusion, equality of opportunity and a belief that everyone had something good to offer to the community.

He pioneered Friday afternoon activities, believing that education was about more than books, and developed the navigation department. He worked loyally for the Educational Institute of Scotland, where he was chair of the education committee, and subsequently had a fellowship bestowed on him. He was also a member of the General Teaching Council. He was a passionate advocate for children’s rights, no matter their background, age, sex or colour. Ian participated fully in the life of the town he loved. When there was a move to tear up the flagstones on the street, he mobilised resistance and saved them. He worked for the museum and Orkney Heritage. In the evenings at Thistlebank, there was home-brew and hospitality, folk songs, story-telling and rumbustious political argument - you never knew who you might be sharing the sofa with, but you knew you’d have a great time.

There was always time for painting, in all weathers. When he retired, he worked harder than ever, out on the cliffs or down the pier. He illustrated some of George Mackay Brown’s books, was a member of the Society of Marine Artists and exhibited in London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen and, of course, Orkney and Shetland. After his retirement he carried on painting with even greater zeal, and was preparing for another eagerly awaited exhibition in Edinburgh when, in 1997, he suffered the first of the strokes that crippled and ultimately killed him. For his memorial he leaves us the stirring example of a great fighter for truth and justice, and a richly evocative display of paintings on countless Orcadian walls - and far beyond his islands.He learned how to use a computer: just before he died, he was learning how to use a zimmer, and enjoying the 50th anniversary dinner of the debating society he helped found.