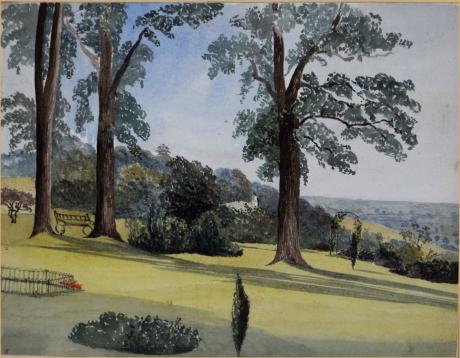

inscribed and dated in the margin "View of the Lawn , Woodbury Hall, Everton, 1866"

George, Earl of Macclesfield, when he married Lane's eldest daughter, came into possession of the Woodbury estate about 1746. He was a president of the Royal Society and died in 1764. Nathaniel Richmond, a landscape gardener and contemporary of ‘Capability’ Brown, landscaped the grounds between 1760 and 1767. There was an informal park, a separate and distinct walled garden and a serpentine belt of bushes and occasional clumps of shrubs. Richmond was working between 1764 – 68 on William Pym’s Hasells Hall estate a few kilometres down the Greensand Ridge towards Sandy. George’s grandson, the third Earl, ran out of money in 1803 and sold it to Rev. John Wilkinson (Rev. William Wilkieson in VCH Cambs.; Alum. Cantab 1752-1900; Complete Peerage, viii. pp.334-5). According to Major Wills of Everton Heath it was a Rev. William Wilkinson of Bath who bought it in March 1804 from the then trustees - Lord Heathfield and John Fane). He then proceeded to build a new mansion in another part of the grounds that was named Woodbury Hall.

The cost of the Woodbury estate was £29,000, the present day equivalent of about £1 million. It was much larger than it is now. (Notes of Major Wills, Everton Heath.) The core of Woodbury Hall was built between 1803 – 1806. In 1832 Wilkinson leased the house for five years to the Rev. Thomas Shore, M.A. of Wadham College, Oxford. His family's stay in the village provided considerable insight into life in Everton during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Shore had been living with his wife and four children at Brook House in Potton where he made a living as a private tutor, preparing the sons of the nobility for entrance to Oxford or Cambridge. His students lodged at his house and included the earl of Desart from Ireland, Lord Granville, Lord Ipswich, Charles Howard and Arthur Malkin. He participated in performing church services locally but never took up the priesthood because of his religious doubts. The children had health problems in Brook House and the move to Woodbury on Christmas Eve, 1832, was partly on health grounds. 'we find Potton agrees very ill with our health, while Woodbury is remarkably healthy, and is situated on the celebrated Gamlingay Heath.' (Gates, B.T., (1991), 'Journal of Emily Shore,' University of Virginia, p.23) It was also to provide accommodation for his students. His youngest daughter, Emily, can be thanked for her details of Woodbury and the surrounding area as her journals detailing her stay in the house have been recently published.

She was a remarkable young lady by any standards. Born in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, on Christmas Day, 1819 she had . When she her first work published when she was eight! It was a sixteen page little book with a paper cover and printed in capitals, “Natural History, by Emily Shore, being and Account of Reptiles, Birds, and Quadrupeds, Potton, Biggleswade, Brook House, 1828, June 15th. Price 1 shilling.” She had written a history of the Jews before she was twelve with maps and illustrations as well as a History of Greece and Rome. She had written a conversation between her and Herodotus, two epics, “Witikind the Saxon” and “Cosmurania,” three novels, three books of poems as well as her diaries, drawings, sketches and plans. She had even translated seven chapters of the first book of Xenephon's “Anabasis.” (Ibid. Itroduction, pp.viii-xiii)

The editor of the journals, Barbara Gates, informs readers that Emily Shore is a tough critic of the arts and politics, a keen and experienced observer of nature, and a young woman who knows what she is about as she creates her own personae. She fittingly holds authority over the ins, outs, ups and downs of a young girl's life. She does inscribe the woman's day as a projective male reader might expect her to, but she does much more as well. (Ibid. Introductory, p.xiv)

“Emily Shore, I need not say, went to no High School, no College, no Lectures, passed no Examination, and competed with no rivals; her teaching was that of Nature and Love. Her education had two characteristics: it allowed her own individuality, with all its tastes and tendencies, freely to expand; and it was an education of pure and good home influences. her sole instructors were her parents, especially her father; but much, very much, was done by herself. She made her whole existence a happy schoolroom. Besides the father's lessons so eagerly assimilated and followed out, she had two worlds in which she was her own sole teacher - the world of nature and the world of Imagination.

Her passion for natural History will appear in the earlier journals; it was indeed, in a great degree to her wanderings at dawn of day in the dewy woods, and her late watchings at open windows with a telescope, collecting plants and studying the habits of birds and insects, that she owed the attack of lung-disease which terminated so fatefully and so soon. Her almost equal love of Poetry and of historical knowledge gathers strength through all the later pages. In drawing she had no instructor but her mother; but the taste came spontaneously, and was marked as that for any of the serious studies we have mentioned. From six years old she was accustomed to using her pencil, copying every object she saw.”

'The study of natural history is perfectly inexhaustible. I believe that if I were chained for life to Woodbury, and never allowed to ramble from it more than three or four miles (the utmost limit of my walks), and excluded as I am, by its situation, from all the birds that haunt mountains, rocks, and the seaside (that is, haunting them particularly), and from most kinds that haunt all sorts of waters - I believe I should forever be discovering something new.' (Ibid. p.92) Woodbury was her own “green world,” a place where she observed with scientific scrutiny, noting that “in the the study of natural history it is particularly important not to come too hastily to conclusions, but to study facts from observation frequently and most carefully before any inference is drawn from them.” (Ibid. p.119) She goes on to say that even though she carefully follows her own advice, “still it is provoking to find myself often making blunders from want of observing with sufficient carefulness at first.” (Ibid.)

The following extracts help shed light on many aspects of life at Woodbury at this time. Remember she was only thirteen when she started the journal. Dec. 14, Friday. - There is going on a sale of Mr. Wilkinson's furniture at Woodbury, and papa went to attend at it. When he returned he told us a story of what had happened. he rode on horseback, and on his way heard the fox-hounds for some time; he knew that they were to throw off that day, and hoped not to get in their way. However, he arrived safe at Woodbury. The auctioneer, Mr. Carrington, was at his work, when a cry was heard of, “There they are!” Behold, the whole set of hounds, pursuing the fox, dashed through the garden, over the beds and everything! Papa was, of course, not highly delighted, but everyone else was in ecstasies. The ladies jumped up and clapped their hands; Mr. C. blew a horn which he had in his pocket or somewhere, and leaped out of the window into the garden, with all the ragamuffins after him. Papa, finding it in vain to try and stop them, walked out with Mr. Wilkinson to see if he could not hinder them from doing damage. Mr. W. ordered the door of the courtyard to be opened, that the fox might pass through; but, unluckily, there was no one to open it, and he was obliged to turn back, the dogs quite close to him all the way, and even brushing by papa. The animal made the greatest exertions, but could only reach the greenhouse, and there the hounds killed poor foxey; he was quite unhappy, and with his tail between his legs. Just then the hunters came up; they had taken care to dismount, all except two most ungentlemanly fellows, who leaped over the haw-haw, cutting up the turf sadly. The fox was now handed about to be seen, the hounds surrounding the hunters, and great delight was shown by all; but papa pitied the poor creature, and several times expressed his indignation, not against the intrusion into the garden, for that he could have borne with perfect good temper in the pursuit of any rational amusement, but against the general barbarity and cruelty of the fox-hunters, whom he detests. He says that he never before saw a fox so closely pursued. Even after the body was taken away, the place smelt quite offensively. (pp.24-5)

Jan. (1832) We took a walk with mamma across the cow-pasture, the first of the three fields leading to Everton. It is a very pretty little fields, hilly, and partly covered with broom. It slopes down towards Foxhill Wood, the wood at the bottom of our garden...

Jan. 12 - We had a long game of play in the garden. The flower garden, which is very large, is divided from the kitchen garden by a noble laurel hedge. Under this hedge runs a path, and there is another path between it and the kitchen garden, which is surrounded by a brick wall. The second path runs all round the kitchen garden, and is entered in two different places by openings in the laurel hedge, which runs round two sides of it. The laurel hedge is double, and the two rows meet together above, so we found that the interior is a very noble palace. This suggested the idea of playing kings and queens.' (p.30)

Dec.27, Thursday. - Today's newspaper announces that Antwerp has capitulated to the French, who are besieging it in behalf of the Belgians, and to whom they are to give it up. The commander of the fortress was General Chasse. The account of the elections was very entertaining; I read it as usual to the children. It always happens that the Reform candidates are cheered and applauded while the Tories are hissed and assailed with groans. The tories have been behaving most shamefully, bribing and threatening the electors to the utmost degree; but they are generally unsuccessful.

Dec. 28, Friday, - After breakfast, when we were all sitting together in the library, the conversation turned on the late capitulation of the citadel of Antwerp. Papa made some promiscuous remarks on the war, of which I will put down what I remember. “The free navigation of the Scheldt has always been a great object with the other powers, the Dutch have as strenuously opposed it; but it is a free gift of Nature, and ought to belong equally to all the countries through which it runs... The King of Holland is a thorough money-making merchant. he himself trades; he monopolises at the expense of his subjects.

Dec. 30, Sunday, - Papa said also that during the war, when the farmers were rich and flourishing, and were amassing thousands upon thousands, they showed the most brutal indifference to the poor who were perishing around them; but that now their turn came, they were getting poorer and poorer, their rents were not paid, and they were eaten up by the poor rates. (pp.28-9)

Jan. 25. ...mamma remarking that the Conservatives had still a strong party in England, papa assented, and then said that the late election cost Mr. Stuart, the Tory member, £20,000. This was chiefly spent in indirect bribery, by entertaining people in public houses, “a beastly way of spending money.” (p.32)

May 16, Thursday (1833) - I did wake up at the proper time, or was woke by the children; and at five o'clock Louisa and I took an exquisite walk through the wood (Whitewood). We went very slowly, and at almost every step Louisa called out, and with justice, “Oh, wonders!” The nightingales were singing in great numbers; and we saw two of them perched in the middle of a tall oak. There was also a blackcap hopping among some low bushes... Mamma takes a walk in the wood every morning, to hear the nightingales and gather lilies of the valley, which are now extremely abundant, and when gathered scent almost half the house; besides which, they are very beautiful. I particularly admire the curl outwards of the blossom.

May21, Tuesday (1833)- At about half-past-six I went out alone into the wood. It is on one side very thick and entangles, full of briars and bushes; but on the right it is covered with grass, free from underwood, and filled with tall firs and a few other trees. I went into this part, and for, I should think, ten minutes watched a nightingale flitting about from tree to tree, and often perched on a tiny twig, so slender that it seemed unable to support it, and even shook. he was singing all the time.' (p.52)

March 25, Tuesday (1834) - I discovered in my walk today a very pretty little spot, in a kind of hollow, below the cow-pasture and the other fields between Woodbury and Everton. It was a large orchard, on a high grassy island, surrounded by a piece of water, which is in most parts perfectly clear and bright, and about forty or fifty feet wide. On one side the channel is nearly dry, and filled with rushes. The banks are very high all round, on the outer side shaded with blackthorn and filbert; on the inner side they ate thickly covered with dog's mercury, primroses, bluebells, a few cowslips, and splendid dark-blue violets. There are also very entangled thickets of thorns, brambles, and briars, and several tall ash trees and willows. This spot is haunted by a great many different birds - blackbirds, missel-thrushes, rooks, carrion-crows, robins, wrens, fauvettes, long-tailed titmice, a handsome kite, and above all, willow-wrens.' (p.73)

March 27, Friday (1835) We entered the orchard today, and as we were walking about it, a fox suddenly splashed into the moat, and, jumping out on the other side, ran off over the cow-pasture. A gentleman's house, in the reign of Elizabeth, stood on the ground now occupied by these moated fields and orchards. (p.91)

Woodbury, June 23, (1834) - There was a tea-party at the Astell's. Mamma, the gentlemen, and all of us went, so that, with the Clutterbucks (of Tetworth), Paroissiens, and some others there were twenty-five in number. We drank tea out of doors, while the gentlemen of the party were engaged at cricket; then followed archery and Les Graces, during which I contrived to keep close to Miss Caroline (Astell), and had a great deal of merry converstion with her, of which the following is a sample:-

Emily. I have a question to ask you. At balls and such places, what do people talk about? If they talk about neither sciences nor natural history, I shall set them down as thoroughly stupid.

Miss Car. Stupid! Oh dear me! let me see - they talk about neither sciences nor natural history.

Em. Stupid people! What do they talk about?

Miss Car. About? Oh, music.

Em. Music?

Miss Car. Yes, music.

Em. Well, music's allowable - very proper. What else?

Miss Car. Yes, they talk about music, and how hot the last party was, and which they shall go to next; and they talk scandal, and on the works of the day.

Em. Dear me! what foolish people! to talk about such absurd things! And do you really like to go to such places, Miss Caroline? Do you actually like it?

Miss Car. Yes, very much indeed (!!!).

Em. Like it! How horrid! How can you like it? What a very great waste of your time, when you ought to be learning and improving your mind, to go to balls and talk nothing but nonsense! Where is the pleasure of it? Do you not think it a waste of time?

Miss Car. Yes, I confess it is; it is a corrupt habit, but when once you have got it., you can never get rid of it.

Em. That is horrible to think of. I hope I shall never get it! But if amusement is your object, why don't you study natural history? There's no amusement so great as that.

Miss Car. But I confess that I don't like natural history.

Em. Oh, how very wrong!. You ought to like it.

Miss Car. But nobody taught me; when I was a child nobody took pains with me.

Em. very true; then it is not your fault. But now, may I ask you, Miss Caroline, when you once begin in the season to go to parties, at what rate do you go? how many in a week?

Miss Car. Oh, why - sometimes to three in a night.

Em. Three in one night! What a waste of life. (p.75-6)

May 12, Tuesday (1835) My usual walk now is to go through the lanes to Everton, descend the Tempsford Hill to hear the tree-lark, reascend it, and return across the heath and through the wood. In passing the heath I go rather out of the way, through a very pretty part, enclosed by a high hedge; it is quite covered with gorse in full flower. here I generally sit down for some time on the gorse, under the high gorse-bushes, telling stories to such of the children as are with me, according to my practice, which I shall continue. All round us stone-chats are flitting from twig to twig, making their clicking noise; ox-eyes are chirping, blackcaps and willow-wrens singing; all which to the delicious scent of the gorse and the perfect retirement of the place, make it quite delightful. (p.94)

June 23, Tuesday (1835) I shall now copy out into my journal a short set of notes, which, in imitation of one in the Penny Magazine, I kept this spring of the progress of vegetation, and the appearances of birds and insects.

Jan. 3. Brimstone rarely seen.

14. Aconite and crocus bloom.

Skylark ascends.

29. Blackbird, thrush, blue-tit, sing.

Feb. 5. Scentless violet forms flower-buds at the root.

10. Honeysuckle in leaf.

Hazel covered with catkins.

24. Greenfinch chirps.

26. Bunting sings.

Mar. 2. Sweet violet blooms.

6. Golden wren sings.

13. Bees come out.

Brimstone abounds.

16. Coal-tit sings.

19. Primrose and ivy-leaved ranunculus bloom.

26. Nettle-butterfly seen.

28. Thrush lays eggs.

April 1. Peacock and cabbage butterfly appear.

2. Willow-wren sings.

Glow-worm rarely shines.

6. Marsh marigold, cowslip, oxlip, bluebell, bullace, black-thorn, pear, bloom.

7. Ground-ivy blooms.

Blackcap sings.

Spotted orchid and wood anenome bloom.

9. Blackthorn and bullace in full flower.

10. Redstart returns.

April 13. Nuthatch whistles.

Germander speedwell blooms.

14. Swallow begins to appear.

Cuckoo heard.

20. Larch and hawthorn in leaf.

Nightingale returns.

22. Zephyr butterfly seen.

Birch looks green.

Leaf-buds of oak burst.

Horse-chestnut nearly in leaf.

Greater stitchwort blooms.

Tree-lark and swallow sing.

May 3. Leaf buds of lime burst.

Crab in full flower.

Lily of the valley in bud.

6. Birch in leaf.

Hawthorn begins to bloom.

Pedicularis, tormentilla, Geranium citutarium, bloom.

Redstart sings.

9. Cockchafer appears.

Yellow wren sings.

leaf buds of oak quite burst.

Jack-in-the-hedge in full flower.

14. Swift returns.

Blue-bell in full flower.

Young starlings fledged.

16. Sphinx apiformis seen.

Orange-tip abounds.

Tree-creeper lays eggs.

22. Young coal-tits fledged.

June 5. Black woodpecker (very rare) lays eggs.

10. Young chaffinches and blackbirds fledged. (p.107)

August 9, Sunday - In the evening I walked to the heath to see some poor people of the name of Betts, whom I sometimes teach a little. They are miserably poor, and live in a mud cottage, built by the man himself, and containing only two rooms for themselves and six children. The man can read, and is tolerably intelligent; the woman is deplorably ignorant, and knows nothing whatever of the doctrines of the Christian religion, so that she requires the very simplest instruction.

Another family, of the name of Barford, lives close by; these also I sometimes go to see. They are a very cleanly, industrious, worthy couple; they have just lost a daughter of a decline, whom I used to go and read to sometimes while still ill. She died July 20. I saw her corpse the next day; it was a very affecting and melancholy sight. It was the first I have seen. The deadly pale of the countenance, the whiteness of the lips, and the unmoving look give a dead body a ghastly appearance. (p.117)

Oct. 2, Friday (1835) As Richard and I were sitting in the library, beginning our lesson with papa, at about half-past-six, a curious interruption occurred. The footman announced that Mr. Clutterbuck wished to speak with papa, who thereupon went and brought him into the library. Mr. Clutterbuck then informed papa of his errand. There is a notorious poacher about here, named Page, for whose arrest a reward of twenty pounds has been offered. The clerk of Everton was knocked down and injured the other day in the attempt. Mr. Clutterbuck and Mr. T. St. Quentin (the magistrate) sent for two Bow Street officers to take him up. He eluded them; but in the mean time two men committed a daring and impudent theft of two ducks at a farm house close to our house, about two days ago. To-day they were arrested at Gamlingay by the Bow Street officers, handcuffed, and ready to be committed. Mr. Clutterbuck asked if he and Mr. T. St. Quentin could examine them in this house, on account of it being in the county of Cambridgeshire. He had brought the officers and prisoners along with him. Papa, of course, agreed. Just then entered Mt. T. St. Quentin and Mr. Foley, another gentleman who is visiting at Everton. The servants' hall was lighted up; pen, ink, wafers, and paper were provided. They adjourned thither; the policemen, prisoners, and witnesses were brought in; papa, Mr. Foley, R., M., and the five pupils were present as spectators; and the examination began. It lasted about half an hour. The prisoners were fully committed and sent to Cambridge Gaol to await their trial at the next quarter sessions, which will be in less than a fortnight. Their names are Samuel Gilbert and John Baines. The Bow Street officers were named, one Goddard, the other Fletcher. The witnesses were three, -our footman; Green, the owner of the ducks; and Larkins, the man who saw them steal them. One of the prisoners being asked if he had any questions to put, merely inquired of Larkins, in a drawing lingo, “Where did you ever see me catch a duck?”

Larkins (in a similar tone). “At the ould pond.”

Gilbert. “Oh, did you?”

Mr. St. Quentin examined the men, and Mr Clutterbuck acted as his clerk.*

*It seems difficult now to believe that for this attempt to steal two ducklings, in the thieves were interrupted and ran away, these poor young men, scarcely more than lads, were sentenced to seven years' transportation. The explanation probably was that they were believed to be poachers. - ED. (p.123-4)

After several visits to London to see doctors it was recommended that she should live close to the sea in a warmer part of the country and so, on October 3rd 1836, Emily left Woodbury to go and live in Exeter. Her health did not improve and eventually her family moved to Madeira where Emily died of consumption on July 7th, 1839 aged only nineteen. She was buried under cypresses and orange trees in Funchal, on the island of Madeira.

Such was the detail that she used that it is thought that, had she lived, she would have been one of the leading authorities on natural history. Whether she met Alfred Newton, the Professor of Zoology at Cambridge University, is not known. Newton was a Cambridge ornithologist who was living in Everton in 1848. It is known that she met Alfred Tebbut, a Potton trader who provided her with many details about bird life and natural history. (Author’s conversation with Anne Harvey, London, Boo Matthews and Anita Lewis, Potton)

According to Fowler’s History of Gamlingay, in 1837 the house was vacant and the following year Rev. Wilkieson sold it and part of the estate to Mr. (later Sir) William Booth, thought to be of the Booth's Gin family. In 1839 Wilkieson died, and his son William sold the remaining part of the estate to Booth. However, shortly afterwards, Booth tired of the place and moved to Paxton, near St. Neots, and in 1858 sold the house and estate by public auction. the estate became divided. 400 acres were sold to Mr. John Foster of Sandy. The remainder, with the mansion, was bought by Mr. John Harvey Astell. (Fowler, E.J. op.cit. p.9) However, the Victoria County History states that the estate had been split by 1844 with Wilkieson holding 315 acres. (C.R.O. Q/RDc 67). Rev Thomas Brown held 380 acres at the western end of Woodbury and Sir Williamson Broth held 315 acres around Old Woodbury.

Following the passing of the parish Enclosure Act in 1844 Rev. Wilkieson arranged the construction of sixty houses in fourteen blocks which became known as the Colony (TL 215513). They were completed by about 1850 on two parcels of land about 61 acres in extent (Gardner’s Directory 1844, p.328; CCRO. Q/RDc 67) The bricks were most likely from the local brickworks to the east and slates brought in from Wales. The general architectural style was gothic with “rusticated openings and cast-iron casements. Many of the buildings have been modified or enlarged and the original holdings can no longer be identified. The block closest to Woodbury Hall were built to a superior specification or white brick, carstone and thatched roofs. (RCHM, p.109-110)

By 1858 Broth held 457 acres in Gamlingay and Everton which he sold to Mr Beadell. (C.U.L. Maps. ) The Astell family had been living in Everton House since 1713 but it had fallen into such a serious state of disrepair that Clare College refused to renew the lease when it expired in 1850. They moved into Woodbury Hall in 1860. (Family documents in possession of Lady Errol) Most of the old house was demolished. The only remaining part is the old stable block which became known as Park Farm. The front lawns reverted to agricultural use and in the 1960s a private housing estate was built on the site. It was appropriately called The Lawns.

Many alterations were made to the house and gardens of Woodbury Hall. A water-driven corn-mill was erected in one of the buildings in 1858. (R.C. H. M. Cambs. i, p.110) There was a period of expansion and modernisation during the second half of the 19th century. In 1868 the gardener's cottage was built and in 1884 the new buildings at Storey's Farm were constructed. After J.H. Astell died on January 17th 1887 the estate passed to his son William Harvey Astell. He died in 1895 leaving a widow and three children, Ison and two daughters, all minors. His widow married Lord de Lisle and Dudley and the three Astell children were brought up at Penshurst Place in Kent.

She leased out the Woodbury estate for 18 years, during which time it had four tenants. When the lease expired in 1926, Richard John Vereker Astell, took possession when he was 35. When he was 21 he had sold various parts of the Heath and some of its cottages to raise cash. The house and land were requisitioned during the 1939-45 war and it was occupied initially by evacuees from the bombing of the cities, then troops from Dunkirk and finally by various units of the RAF, Artillery and Engineers. With the construction of the secret airfield at Tempsford the tree-lined avenue from Everton Church to Story Farm was uprooted to allow the planes an easier take off over the top of the Greensand Ridge. Opposite the house was built an Engineer Store as well as a prisoner of war camp. On 3rd June 1944 there was a serious fire in the house. How it happened has never been explained but it destroyed the south end of the house as well as the roof. Interestingly, the army de-requisitioned the house the next day. Locals suggest that it was to avoid paying any more rent.

After the war repairs and rebuilding started in about 1951/2 during which time the house was redesigned. The south end was turned into a courtyard and the whole second floor was taken off. As a result the views over the Bedford Plain would have been dramatically reduced. The interior was also reconstructed by Basil Spence. He was also the architect who built Coventry Cathedral and the multi-storey blocks of flats that dominated inner cities during the 1960s and 70s. Richard Astell and his wife reoccupied the house in 1955. He died in 1969, leaving the estate in the possession of his widow, Lady Astell, who died in 1994. (Notes of Major Wills, Everton Heath.)

Her niece, Isabelle, took over the estate with her husband Lord Erroll and the Hall was considerably refurbished during the late-1990s.