S Noell

Taxidermy, or the process of preserving animal skin together with its feathers, fur, or scales, is an art whose existence has been short compared to forms such as painting, sculpture, and music. The word derives from two Greek words: taxis, meaning order, preparation, and arrangement and derma, meaning skin. Directly translated, taxidermy means "skin art."

According to John W. Moyer, a staff member at the Chicago Field Museum of Natural History famous for his comprehensive studies on the development of this process, in his book Practical Taxidermy, the modern form of taxidermy greatly differs from the taxidermy of antiquity. In ancient times, although considered some form of "art," it was a process of animal preservation; in contrast, modern taxidermy methods seek to produce lifelike mounts of wildlife by accurately modeling the anatomy of animal specimens as they might appear in their natural habitat. According to Albert B. Farnham, in his book Home Taxidermy for Pleasure and Profit, although its methods greatly differ over time, the art reveals that there existed then as now the desire to preserve the trophy of the hunter's prowess and skill in natural objects.

As documented in Frederick H. Hitchcock's 19th-century manual entitled Practical Taxidermy, the earliest known taxidermists were the ancient Egyptians and despite the fact that they never removed skins from animals as a whole, it was the Egyptians who developed one of the world's earliest forms of animal preservation through the use of injections, spices, oils, and other embalming tools. As early as 2200 BC, they embalmed the bodies of dogs, cats, monkeys, birds, sheep, oxen, and any other pets of Egyptian royalty and buried them in their Pharaoh's tomb.This art of embalming was effective, not for the purpose of having the specimens look natural or for exhibition, but to satisfy the tradition of the times. Likewise, according to Thomas Brown, a 19th-century naturalist and malacologist, "Egyptian preservation attempts were prepared in such a manner as to produce no pleasurable sensations in examining them; instead, they were remarkable only for their great antiquity and spiritual beliefs." Though these people did not seek to preserve animals for modeling their anatomy as they might appear in a natural setting, the ancient Egyptians’ ability to preserve the carcasses of animals as immense as the hippopotamus (a mummy of which was discovered in Thebes) reflect the veracity of these early textual claims to the art's earliest roots.

Carthaginian Empire

Other instances of ancient roots in taxidermy date as far back as five centuries B.C. in the record of the African explorations of Hanno the Carthaginian. Within the past five centuries, an account is given of the discovery of what were evidently gorillas and the subsequent preservation of their skins, which were hung in the temple of Astarte where they remained until the taking of Carthage in the year 146 B.C.

Western/Central Europe

The people of Greece, Rome, ancient Britain, and other northern lands could be said to have practiced a form of taxidermy in the tanning of skins used for clothing. Because they had no other means of covering their bodies, early Europeans developed methods of preserving the skins of lions, tigers, wolves, and bears for survival.

Native Americans

Much like the people of Greece, Rome, and northern Europe, many Native American tribes such as the Sioux, Cherokee, Pottawatomie, and Cheyenne preserved the skins of foxes, raccoons, bears, buffalo, porcupines, and eagles to produce and decorate their clothing, tools, and equipment. To this day, remnants of such Native American tribes continue this early form of taxidermy in tanning and preserving animal carcasses for traditional and cultural purposes.

About 400 years ago, the first mounting attempt on record included the preservation of birds in the Netherlands. As reported, a wealthy Dutch trader obtained an aviary of exotic birds that were brought back from the East Indies. Due to the neglect of the bird keeper, every bird died of suffocation; but as the owner wished to keep their skins and plumage for display, they were skinned and preserved with spices brought to Holland, also from the East Indies. The skins were then wired and stuffed with cotton and tow and were ultimately posed in natural positions.

One of the first published works on taxidermy is found in Natural History, published by the Royal Academy of Vienna in the beginning of the 18th-century. Containing a treatise on the dissection of birds and animals, the work also makes reference to the preservation of birds in the Netherlands more than a century before.

R. A. F. de Reaumur

According to John W. Moyer in another one of his works for Encyclopedia Americana, one of the earliest published works on taxidermy is R. A. F. de Reaumur's Treatise, which was published in 1749. In this work, Reaumur discussed the preservation of skins of birds; however, because his plan was simply to mount birds with wires – as had been done over two centuries before – it did not find much favor among other taxidermists. Instead, his method spurred the development of a new system of preservation in which one cut the skins longitudinally into halves, filled one half with plaster, fixing the skin to a backboard, inserting an eye, painting on a beak and legs, and then mounting the bird in a framework of glass. For the next several decades, this process became the standard method of European taxidermists.

British Museum

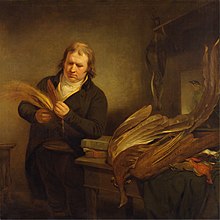

Mr. Thomson, Animal and Bird Preserver to the Leverian and British Museum in 1802

After rising to prominence in 1759, the British Museum, which, was then known as the Montagu House, contained the world's largest collection of animal skins in the 18th- and early 19th-century, displaying a total of 1886 mammals, 1172 birds, 521 reptiles, and 1555 fishes; however, a great proportion of these were not stuffed specimens, but simply bones and preparations of skins. Soon after the Museum's opening, these natural history collections drew a great deal of interest from the public, thus demonstrating the rise in popularity of the art into the 1800s.

Following the restoration of peace in Europe after 1815, Great Britain witnessed continued growth in the Museum's status as naturalists and taxidermists found that the public had then time and the inclination to devote themselves to such collections.

Perhaps the most notable event that provided an impetus to a more accurate, realistic modeling of specimens in their natural settings was the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Displaying a plethora of exhibits from all around the world in various forms, it was the first time in history where taxidermists from across the world gathered together and presented modern, innovative methods pertaining to the art.

Rowland Ward studio

In the late 1800s, British taxidermists established the Rowland Ward studio was established in London; the individuals who worked there are credited with many improved methods in taxidermy. It was at Ward's that the Lion and Tiger struggle (despite its unnatural display of history) was designed and mounted, then considered the finest animal exhibit of ancient or modern times. This display was initially moved to an exhibit in Paris, but was soon returned to the Sydenham Crystal Palace in London.

Jules Verieaux

Following the creation of the Lion and Tiger exhibit, a prominent French taxidermist named Jules Verieaux mounted another animal group, though different in design. Entitled The Courier, the display depicted the figure of an Arab man (presumably formed from some type of wax) seated upon a stuffed camel being attacked by two lions.This spectacle was first exhibited at the Paris Fair of 1867 and was later purchased by the American Museum of Natural History. Like the Lion and Tiger display, Verieaux's work – along with those of other European taxidermists such as Edwin Ward – demonstrated the development of taxidermy into its modern form as its artists paid a greater deal of attention to animals’ anatomical movements and features.

Influence of Victorian society

Although the French and Germans progressed in the practice of taxidermy prior to the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, the English made several improvements in methodology and skill in the years that followed. Much of this can be attributed to the culture of Victorian Society. According to Paul Farber, a researcher at the University of Chicago, in his book The Development of Taxidermy and the History of Ornithology, the art of taxidermy was first brought into popular regard by the Victorians, who were enthralled by all tokens of exotic travel, especially to any domesticated representations of wilderness. Whether it was having a glassed-in miniature rain forest on the tea table or a mounted antelope by the front door, members of the elite class relished the art as a manifestation of one's knowledge, wealth, and artistry. As Victorian English society reached its pinnacle near the end of the 19th-century, technique and methodology of the art progressed; however, compared to modern standards, poses were still fairly stiff and expressionless.