The most plausible theory as to how pheasants reached our shores is through import from France by Roman officers who bred them for the table. Although originally introduced by the Romans, the actual country of origin is still a much-debated topic. The most realistic answer is that pheasants were imported to Southern Europe from Asia.

After this, the first recorded documentary evidence of the existence of pheasants is in the year 1059 in relation to an order of King Harold. Although mentioned, it is not thought that they were widely distributed at this stage and Normans passed laws to ensure they were protected. These laws allowed the pheasant population to increase significantly and by 1100, Henry I granted the Abbot of Amesbury the right to kill pheasants.

It was not until practical hand-held firearms arrived in Britain around 1500 that shooting pheasant for sport really took off. Henry VIII is known to have enjoyed shooting and had a French priest appointed as a ‘fesaunt breeder’. Since this time, pheasant shooting has continued to be a popular Royal pastime.

Until the late 17th Century, birds were shot when stationary on the ground or perched. By the 18th Century, significant improvements in shotgun technology had been made and with the introduction of the double barrelled breech loading gun in the mid 19th Century saw the development of the driven shoot. A new concept at the time, instead of walking towards the birds, these shoots were formally organised with the guns at a fixed position or pegs whilst the birds were driven towards them. This technique, as we use today allows for more challenge with a variety of high flying birds and the Keeper able to control the amount and general direction of the birds.

Shotguns were improved during the 18th and 19th centuries and game shooting became more popular. To protect the pheasants for the shooters, gamekeepers culled vermin such as foxes, magpies and birds of prey almost to extirpation in popular areas, and landowners improved their coverts and other habitats for game. Game Laws were relaxed in 1831 which meant anyone could obtain a permit to shoot rabbits, hares, and gamebirds, although shooting and taking away any birds or animals on someone else's land without their permission continued to be the crime of poaching, as it still is.

Hunting was formerly a royal sport, and to an extent shooting still is, with many Kings and Queens being involved in hunting and shooting, including King Edward VII, King George V(who on 18 December 1913 shot over a thousand pheasants out of a total bag of 3937),[4] King George VI

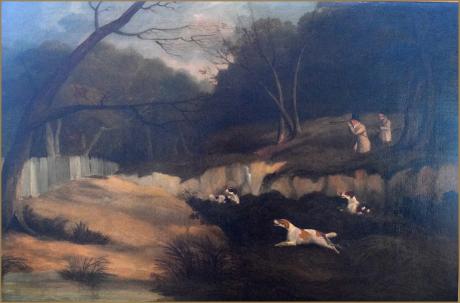

Dean Wolstenholme, the elder (1757–1837), animal painter, was born in Yorkshire. He was probably the son of Sir John Wolstenholme, baronet, and was descended from Sir John Wolstenholme (1562–1639), who was one of the farmers of the customs in the reign of Charles I and left extensive property, including Nostell Priory, Yorkshire, to his son John, who received a baronetcy in 1664. Dean Wolstenholme spent most of his early life in Essex and Hertfordshire, where he lived successively at Cheshunt, Turnford, and Waltham Abbey. He was an enthusiastic sportsman who occasionally painted sporting subjects for pleasure; Sir Joshua Reynolds is said to have predicted that he would be a painter in earnest before he died. In 1793 he became involved in litigation over some property at Waltham, and after three unsuccessful chancery suits was left with few resources, so he adopted painting as a profession. On 18 January 1795, at St Olave, York, he married Mary Stabler, with whom he had a son, (Charles) Dean Wolstenholme (1798–1883).

About 1800 Wolstenholme moved to London, and settled in East Street, Red Lion Square. In 1803 he exhibited his first picture, Coursing, at the Royal Academy. He is best known for his paintings of his favourite pastime—fox-hunting—but also painted shooting scenes; portraits of hunters, cattle, sheep, and dogs; racecourses; and, in 1824, The Interior of the Riding School of the Light Horse Volunteers (which included several portraits). Many of his works were engraved; Fox-Hunting (exh. RA, 1804) for example was reproduced in aquatint by Thomas Sutherland, Reeve, and Bromley, and published by Ackermann. The Epping Forest Stag Hunt (1811) is regarded as his masterpiece. After 1826 he painted little. He died in 1837, at the age of eighty, and was buried in St Pancras churchyard.

Wolstenholme 'was a man of remarkable physical strength; it is said that on one occasion he made a bet that he would carry two sacks of flour up a ladder, and won it' (Gilbey, 249). Of his hunting scenes—which remain popular, particularly in America—Walter Shaw Sparrow noted that 'they are vigorous, and show a liking for hilly land, and far horizons, and the charm and weight of trees' (Sparrow, 83). Although the work of the elder and younger Dean Wolstenholme is sometimes confused, Sparrow observed 'a depth in this primitive that I do not find in his son'.

- Ernest Clarke revised by Annette Peach Oxford DNB