Thomas Page’s The Art of Shooting Flying Explained of 1767 (a longer and more technical work than those of Blome and Markland) recommended 32in for early season work and, for “after Michaelmas, the birds by that time… grown so shy, that your shoots must be at longer distances”, 39in, adding, “if you intend one gun to serve for all purposes… a three feet barrel or thereabouts” would be ad-visable. Such guns anticipated the range and killing power of a modern shotgun, Markland recommending Full forty Yards permit the Bird to go/The spreading Gun will surer Mischief show.

While the flintlock and trigger-to-bang time continually improved, the next major innovation was the addition of a second barrel. The earliest examples of guns with barrels held together by soldering rather than the stock were French side-by-sides of the 1730s. However, these were slow to catch on in England, the Shooting Directory of 1804 dep-recating their usefulness and equating their French origin with “a great many other foolish things”. Nevertheless, the great English gunmakers Ezekiel Baker, Henry Nock and the Mantons were already producing superb examples, which, with the formerly full-length stock (as long as the barrels) reduced to a “half-stock” (resembling a fore-end), looked much like modern guns.

Rapidity of fire increased with the application of percussion ignition early in the 19th century, especially with the perfected percussion cap of about 1830. However, it was the introduction of a fully functional hinged breech in the 1830s and then of cartridges containing primer, propellant and projectile – and reliable firing pins – that saw the birth of the modern shotgun.

A top hat, beaver hat, high hat, silk hat, cylinder hat, chimney pot hat or stove pipe hat,sometimes also known by the nickname "topper", is a tall, flat-crowned, broad-brimmed hat, worn by men from the latter part of the 18th to the middle of the 20th century. The first silk top hat in England is credited to George Dunnage, a hatter from Middlesex, in 1793. The invention of the top hat is often erroneously credited to a haberdasher named John Hetherington. Within 30 years top hats had become popular with all social classes, with even workmen wearing them. At that time those worn by members of the upper classes were usually made of felted beaver fur; the generic name "stuff hat" was applied to hats made from various non-fur felts. The hats became part of the uniforms worn by policemen and postmen (to give them the appearance of authority); since these people spent most of their time outdoors, their hats were topped with black oilcloth. The Top hat was usually black but the sporting varities were grey, brown and white.

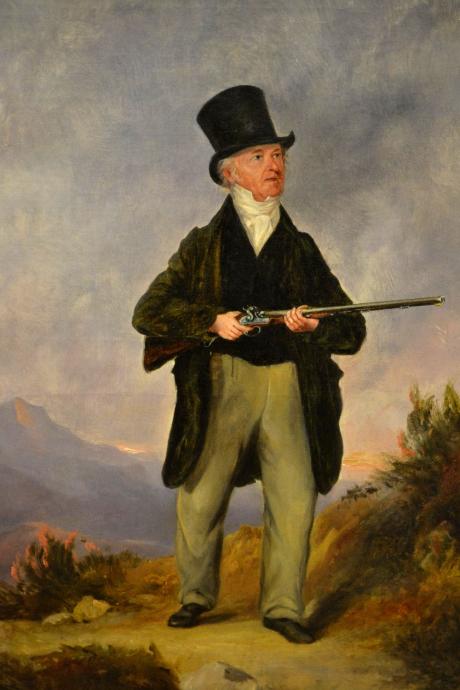

Benjamin Marshall, (1768–1835), painter and racing journalist, was born on 8 November 1768 at Seagrave, Leicestershire, the only surviving son of eight children born to Charles Marshall and his wife, Elizabeth (d. 1772). Benjamin Marshall married Mary Saunders (d. 1827) of Ratby on 12 November 1789 and is recorded as being a schoolmaster in the will of his brother-in-law, dated 1791. However, he must have already shown a talent for portraiture for in the same year, on the recommendation of William Pochin of Barkby Hall, MP for the county, he was apprenticed to the portrait painter Lemuel Francis Abbott.

It is said that Ben Marshall (as he was known) was so impressed by Sawrey Gilpin'slife-size painting Death of a Fox, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1793, that he decided to change from portraiture to sporting subjects (Sporting Magazine, Aug 1835, 298). By 1795 the Marshalls were living in London at Beaumont Street, Marylebone, their elder son, Charles, having been born the previous year. Soon after their arrival Marshall met William Taplin, the author of The Gentleman's Stable Directory, and this was to be a turning point in his career. Taplin not only commissioned a portrait of himself, but also paintings of several of his horses. These were hung in Taplin's newly erected purpose-built 'equestrian repository' in the Edgware Road, where they would have been seen by the many fashionable and influential subscribers to his equestrian services. Marshall's portrait of Taplin was engraved for the February 1796 issue of the Sporting Magazine and in August of the same year his first horse portrait appeared, A Son of Erasmus, whose owner is recorded as a Taplin subscriber. Both these works were engraved by John Scott and the working relationship between them developed into a lifelong friendship which, as both admitted, did much to enhance their respective talents. Marshall's connection with the Sporting Magazine continued throughout his life. Sixty of his paintings were engraved as illustrations between 1796 and 1833, and from 1821 to 1833 under the name Observator he became their southern racing correspondent. The Sporting Magazine also records in 1796 that on the completion of three paintings for George III, Marshall was granted an audience of almost an hour with the king and 'all the princesses' (Sporting Magazine, Aug 1796, 255).

Marshall's early works owe much to both George Stubbs and Gilpin, for example Diamond with Dennis Fitzpatrick up (1799, exh. at RA, 1800; Yale U. CBA) and Grey Arab Stallion and Mare (FM Cam.). However, they already show the individuality that in the first years of the nineteenth century was to develop into his own very personal style. This change is best represented in the series of six paintings of horses commissioned by George, prince of Wales, probably executed between 1801 and 1803. These, unlike the three painted for George III, remain in the Royal Collection.

Joseph Farington recorded in his Diary of 28 March 1804 that 'Bourgeois spoke of Marshall a horse painter as having extraordinary ability and that Gilpin had said that in managing his backgrounds he had done that which Stubbs and himself never could venture upon'. This ability to capture the vagaries of the British climate and landscape together with the depth of character in his portraits of all those connected with the sporting world raise Marshall well above the range of the average sporting artist. However, he made no attempt to be elected to the Royal Academy and exhibited there only intermittently between 1800 and 1819. The Marshalls remained at Beaumont Street until 1810, Marshall painting both sporting subjects and portraits including the celebrated boxers John Jackson, John Gully, and James Belcher (Tate collection) and, most strikingly, Marshall's Leicestershire friend Daniel Lambert, the celebrated fat man, who had exhibited himself at a shilling a visit in London during summer 1806 (exh. RA, 1807; Leicester Museums and Art Galleries).

Prompted by Ben's great love of racing, the Marshalls moved to near Newmarket in 1812. There, Marshall 'could study the second animal in creation … in all his grandeur, beauty and variety' (Sporting Magazine, Sept 1826, 318), adding the much quoted adage that 'a man would give me fifty guineas for painting his horse who thought ten too much to pay for the best portrait of a wife' (Sporting Magazine, Jan 1828, 172). His absence from London did not lessen his success and for the next seven years he produced some of the finest sporting paintings of the first quarter of the nineteenth century and arguably the best studies of jockeys ever painted. In September 1819, while he was travelling to his patron Lord Sondes at Rockingham Castle, the mail coach overturned and both Marshall's legs were broken, his head badly cut, and his back injured. He made a remarkable recovery, and the Sporting Magazine reported in October 1820 that he 'had built himself a new painting room at Newmarket and was busily employed' (Sporting Magazine, Oct 1820, 42). That his abilities were not impaired is shown by the striking portrait Thomas Hilton and his Hound Glory of 1822 (Royal Museum and Art Gallery, Canterbury, Kent).

In 1825, aged fifty-seven, Marshall returned to London, purchasing a house in Hackney Road but keeping on his house in East Anglia. His succinct and descriptive racing journalism was still signed 'Observator, Norfolk'. One of his reasons for returning was to promote his younger son Lambert (born in November 1809 and named after Marshall's old friend Daniel Lambert who had died suddenly in June the same year) as his successor as sporting artist and illustrator for the Sporting Magazine. Sadly, Lamberthad little more than schoolboy talent: the earlier works are almost entirely by his father and there are few that do not have some assistance. It is not surprising that not a single painting attributed to him dates from after Marshall's death.

Although there appears to have been no fall in demand for Marshall's paintings or writing, the effects of his coaching accident were gradually lessening his mobility and hence output. In 1834, when the dress of the youngest of his three daughters, Elizabeth (b. 1812), caught fire, he was unable to move out of his chair to assist her and was forced to watch her burn to death. This tragedy, compounded with the death of his wife in 1827, hastened his own end and he died on 24 July 1835 at his home in London Terrace, Hackney Road, London. He was buried with his wife and daughter at St Matthew's, Bethnal Green. Marshall's effects were valued at only £200. There was no studio sale of his unsold paintings and studies, and although the Gentleman's Magazine noted the death of 'the celebrated artist Ben Marshall' (GM, 2nd ser., 4, 1835, 531), he was soon forgotten. He left little mark on the next generation of sporting painters, for despite the fact that John Ferneley was apprenticed to him and Abraham Cooper had lessons with him, his broad style of painting and somewhat bucolic approach to his subjects had little appeal to the Victorians and it was not until early in the twentieth century that he began again to be appreciated.

Marshall is not widely represented in British public collections, where his portraits are more numerous than his sporting subjects. For a broader view of his work one has to turn to private collections. Many of his paintings were exported to the USA in the first half of the twentieth century and are now represented in a number of galleries there, most notably at the Yale Center for British Art at New Haven, Connecticut, which holds the best portrait of the artist. David Fuller DNB.