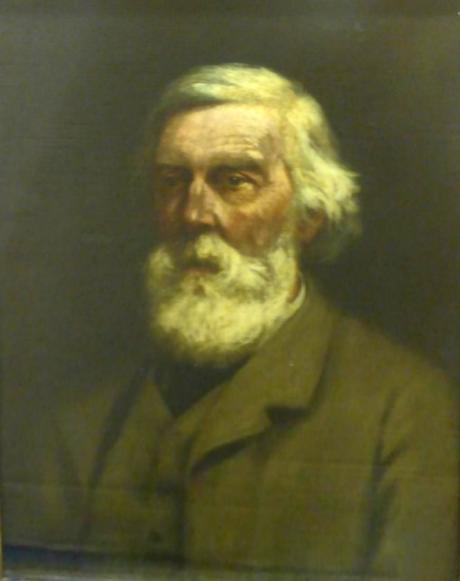

signed and dated "1894"

By descent in the family

Williamson, Alexander William (1824–1904), chemist, was born on 1 May 1824 in Wandsworth, Surrey, the second of three children of Alexander Williamson, a clerk in the East India House, and Antonia McAndrew Williamson, daughter of a London merchant. His father, of Scottish parentage, was a man of high culture and intellect; the family's comfortable financial circumstances were apparently due to his wife's means. He was a friend of the economist and utilitarian philosopher James Mill, who worked in the same office and who lived close by in Wright's Lane, Kensington, after the Williamson family moved there in 1831. About 1840 Williamson resigned his position, and thereafter the family went to live in France and Germany.

As a boy Williamson had weak health, exacerbated by inappropriate medical care; he suffered from blindness in the right eye and myopia in the left, and a stiff and largely useless left arm. Despite these infirmities, he later developed a sturdy constitution. After attending day schools in Kensington, Paris, and Dijon, in 1841 he enrolled at the University of Heidelberg, intending to study medicine. He was, however, soon attracted to chemistry through the lectures and kind personal attention of Leopold Gmelin (1788–1853). In 1844 Williamson transferred to the University of Giessen in order to study under the world-famous chemist Justus Liebig (1803–1873). Here he made a minor sensation with his first published paper, on a subject (the reactions in solution of ‘bleaching salts’) which Liebig had assigned as a simple analytical exercise. Concerning this research, he commented presciently in a letter to his father: ‘the great difficulty in a research such as that I am now pursuing consists not so much in performing the experiments once fixed upon, as in inventing and choosing from those most calculated to attain the desired object’ (Divers, xxvi).

Williamson received his PhD from Giessen in 1845 and the following year took up temporary residency in Paris. Here he became acquainted with the principal French chemists, including Jean-Baptiste Dumas, Adolphe Wurtz, Auguste Laurent, and Charles Gerhardt. He also took private lessons in mathematics from Auguste Comte, the founder of French positivism, who had been recommended to him by John Stuart Mill. Williamson was for a time a committed positivist, and Comte had high hopes that he would establish an English beachhead for his philosophical system. However, Williamson soon fell away from Comtean orthodoxy.

Although Williamson published no research during this period, it appears that it was in Paris that he began his fundamental investigations in etherification and reaction mechanics. In 1849, supported by the eminent chemist Thomas Graham, Williamson successfully applied for the professorship of analytical and practical chemistry at University College, London, which was vacant following George Fownes's death. This was one of the earliest academic laboratories in Great Britain in which students were required to perform practical exercises. Williamson's pedagogical impact was substantial during the thirty-eight years he spent in the Birkbeck laboratory at University College. He had strong opinions on teaching technique—he regarded it as vital to lead from individual facts to general principles, rather than the reverse—and his students seem to have responded enthusiastically, describing him as a splendid teacher. In 1865 he published a successful elementary textbook, Chemistry for Students.

Williamson's novel reaction by which ethers could be synthesized was first announced on 3 August 1850 at the Edinburgh meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. It is no exaggeration to say that this paper marked the beginning of a turning point in the science of chemistry. The Williamson ether synthesis was one of the earliest reactions designed with the intent to build up larger molecules from smaller pieces and remains one of the most elegant reactions in organic chemistry. An ether is a molecule with a central oxygen atom connected to two hydrocarbon radicals; Williamson's reaction allowed the chemist to select each radical in advance and then join them together, thus designing new ethers at will.

But there was an even greater significance to Williamson's discovery. In 1850 European chemists were by no means in agreement on the relative atomic weights of common elements such as carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, and they had no way unambiguously to determine relative molecular sizes. For instance, common alcohol was thought by most chemists to be simply a hydrated form of common ether, whereas Williamson was convinced that ether was about twice the size of alcohol. Williamson's reaction provided a crucial test for this viewpoint. His success in creating a novel asymmetric ether (one in which the two radicals are not the same) was consistent only with the larger formula for ether; the smaller formula would have required the product of the reaction to have been a mixture of two different symmetrical ethers.

Williamson's 1850 paper, two additional, more detailed, articles on the same reaction published about a year later, and a further series of papers on related subjects in the following years were widely influential. They are all collected in Papers on Etherification and on the Constitution of Salts (1902). The theoretical strategy he had designed to demonstrate the true structural relationships of alcohols and ethers was applied to various molecular systems by a number of other chemists during the 1850s. In the process, much of the existing confusion over relative atomic and molecular weights was eliminated, and a revised system, virtually identical to that in modern use, was established. Williamson's work had the advantage (to chemists) of deriving its force entirely from chemical evidence; chemists were inclined to distrust the growing physical evidence, for example from the theory of gases, that tended to support the new ideas which Williamson was championing.

These developments were closely connected with what was then called the ‘theory of types’, and with emergent theories of atomic valence and molecular structure. In his etherification work, Williamson argued for the existence of a ‘water type’, the molecular construction of which could serve as a model for all other organic compounds containing oxygen, in the same fashion that Wurtz's and August Hofmann's ‘ammonia type’ of 1849–50 had provided the model for nitrogenous substances. More broadly, such considerations of molecular ‘types’ led more or less directly to the perception that atoms have definite limited capacities for combination with other atoms, and that atomic concatenations can be discerned and studied. Such structural ideas, which radically transformed chemical science and technology after the middle of the century, were developed under the immediate influence of Williamson's contributions of the early 1850s. The German chemist August Kekulé (1829–1896), who was to be the central personality in the development of the classical theory of chemical structure, spent a post-doctoral stint in London in 1853–5, and ever after acknowledged Williamson as the greatest influence on the evolution of his thinking.

Williamson's etherification studies also had broader implications for the understanding of chemical processes. In the course of this work he proposed a new view of the manner in which molecules interact with one another during the course of a chemical reaction. In place of the prevailing static conception, he suggested a more dynamic model, in which groups of atoms engage in perpetual exchanges until equilibrium is attained or physical forces remove product molecules from the process. His suggestion of ephemeral intermediate entities in chemical reactions was designed partly to oppose the mysterious notion of a ‘catalytic force’, and all of this did much to prepare the way for the later study of reaction kinetics and the emergence of the law of mass action.

By the end of the first six years of his professorship Williamson had published a series of papers describing some of the best chemical research of the century. On Graham's resignation in 1855 he was rewarded by his appointment to the chair of general (theoretical) chemistry in addition to his other duties. The increase in income enabled him to marry Emma Catharine Key (d. 1923), the daughter of a university colleague, Thomas Hewitt Key, on 1 August 1855. They had two children, Oliver Key (d. 1941) and Alice Maude, later Mrs A. H. Fison (d. 1946).

Williamson took his newly expanded professional duties seriously, and his scientific research never really recovered. He was much involved in the reform of scientific education, not only at University College but in Great Britain generally, and even internationally—for instance, in advocating laboratory work for engineering as well as science students, in agitating for the awarding of science degrees in British universities, and in serving as scientific adviser as well as personal host to groups of visiting Japanese students. Williamson's services as a scientific administrator were also much in demand. From 1850 on he was a leading personality in the Chemical Society of London, and twice served as its president (1863–5 and 1869–71). He was much involved with the British Association for the Advancement of Science and was its president for the 1873 session. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1855, served two terms on its council, and was its foreign secretary from 1873 to 1889. These duties doubtless interfered with his research. Yet another reason for the cessation of his scientific work after 1855 was his turn toward industrially related research. He carried out extensive studies of fireplaces, steam boilers, pharmaceuticals, and heavy chemicals manufacture. However, little of this research resulted in useful innovation or financial gain.

Perfectly fluent in both French and German, Williamson was also eloquent in his native language; allied with his incisive analytical powers, his verbal skills made him a powerful advocate for whatever position he chose to defend. Some witnesses refer to a certain propensity to use cutting remarks in debate, but most remember him as a man of exquisite kindness and tact. He never allowed differences of opinion to damage personal relationships with colleagues.

Williamson's most celebrated forensic encounter was with a friend, the Oxford chemist Benjamin Brodie the younger, a noted critic of the atomic theory. Defying his youthful positivism, from 1850 on Williamson had ardently defended the ontological reality of invisibly small atoms, and criticized what was then a fashionable trend towards a certain scepticism regarding atomic theory. When Brodie published his account of a ‘chemical calculus’ whose intent was to eliminate all atomistic reasoning from the science of chemistry (1866–7), Williamson went on the attack. In masterly addresses before the Chemical Society in 1869 and the British Association in 1873 he systematically laid out the overwhelming evidence for atoms and demolished the arguments of the critics, including those of Brodie. Inter alia he argued that there was an implicit atomism even in Brodie's system, and that everyone, including the most ardent anti-atomists, actually used the theory daily, whether they realized it or not. In this, as in his publications of two decades earlier, he represented and helped to form the views of those chemists who were to complete the transformation of nineteenth-century chemistry.

Williamson retired in 1887, and moved to an estate which he had purchased in Hindhead, near Haslemere, Surrey, where he practised agriculture on scientific principles. He died at his home on the estate, High Pitfold, Shottermill, after a long illness, on 6 May 1904. He was buried at Brookwood cemetery, Surrey.

A. J. Rocke DNB

William Biscombe Gardner (1847–1919) was an English painter and wood-engraver. Working in both watercolour and oils, he exhibited widely in London in the late 19th century at venues such as the Royal Academy and the Grosvenor Gallery. From 1896 he lived at Thirlestane Court.

He illustrated a number of books featuring the British landscape (see below), notably "Kent", "Canterbury", and "The Peak Country". He also drew scenes from the Welsh Elan Valley in the 1890s, before it was flooded to form the Elan Valley Reservoirs, which appeared in two books by Grant Allen (see "illustrated Books" below).

However, it was as a fine wood-engraver that he was mainly known, providing illustrations (sometimes large) for English magazines of the day such as the Pall Mall Gazette, Illustrated London News, English Illustrated Magazine and the Magazine of Art. He was a firm advocate of traditional wood-engraving considering it to be the most versatile in comparison to the more conventional methods of engraving andetching, or more recent methods including "process illustration".

He exhibited frequently and widely in London between 1874 and 1893, particularly at the Royal Academy and the Grosvenor Gallery. Gardner was best known as an engraver, particularly for The Graphic, the Pall Mall Magazine, and The Illustrated London News. He also specialized in engraving the work of other artists including Edward Burne-Jones and Lord Leighton.