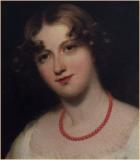

Mostly found in the Mediterranean Sea, coral grows 4-100 meters from the surface. It is composed mostly of calcium carbonate, colored red by carotenoid pigments (Wiki). The stone must be polished, as it usually matte-colored. Control of the areas from which coral could be mined often led to fierce competition between different countries, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries. The deeper meaning of coral leads back to ancient Romans. The story of Perseus, the sea monster, tells that coral the petrified seaweed covered in the blood of Medusa's head. Poseidon used the stone in his palace as well, making coral a prominent component of mythology. The Romans believed in the luck of coral, a sentiment revived by the Victorian era. Children often wore the stone, with the belief that it could cure snake bites or poison. The Etruscan revival in the 19th century brought coral front and center in jewelry, especially from 1845 Italy. Honestly, it had not gone anywhere; the Georgian and Regency eras show a propensity towards the stone that cannot be missed in paintings. Dark reds and pale pinks were most common, even a dyed white coral was not remiss. "But even more prized were ornamented of finely carved coral, in the shape of crosses, roses, hands, cameos, and the like" (Flower and Moore). A coral parure for a young lady would have been considered a prized gift!

BOARDING-SCHOOL EVILS, Godey's Lady's Book. February, 1860.

We well know that there can be but one ruling passion, and as vanity and all that goes to feed it, dress and jewelry especially, is the besetting sin of a school-girl's life, we can but wonder at the blindness that ministers to it deliberately, instead of uprooting any weed of temptation from the path. The rivalries of dress, furniture, and equipage, that make up so much of our social life, begin in the school-room with Eliza's Christmas set of pink coral and Lucy's ill-gotten flounced silk— ill-gotten, since it was purchased with the sum that should have given her mother a comfortable shawl or the children their bird's-eye aprons.

NATURAL ORNAMENTS, Godey's Lady's Book. June, 1860.

“THE month of roses” reminds us how few ladies make use of the most charming of all ornaments for the hair and dress, natural flowers. They load themselves with impossible clusters of muslin roses and jessamine, with dangling pendants of glass and wax, called jet and coral by courtesy; they flash bugles and spangles into your eyes with every turn of the head, while the pendant wreaths of the Spiera Reevesi, and the graceful racemes of the laburnum and the “bleeding heart,” or the perfumed cups of the valley lily, are perishing, unnoticed, in the lawn and garden.

MARY GREY, Godey's Lady's Book, June, 1860

Florrie, too, looked very lovely, in her little white dress and coral armlets and necklace, her golden hair curling in little short ringlets all over her head, and her cheeks the color of a May rose.

CHITCHAT UPON NEW YORK AND PHILADELPHIA FASHIONS, FOR JULY, Godey's Lady's Book, July 1860

Dress for evening, of perfectly plain white grenadine. The under skirt has three flounces of moderate width; the upper one is perfectly plain. There is no pattern, no edge of any description, to the flounces, sleeves, or waist—the richness of the material obviates it— with the exception of a rich satin ribbon, also of plain white, which forms the heading of the berthe, and has a bow on each shoulder and in the centre of the corsage, bracelets and belt-clasp of gold, set with red coral

MISCELLANEOUS, Godey's Lady's Book. August, 1860.

ARTIFICIAL CORAL .— This may be employed for forming grottos and for similar ornamentation. To two drachms of vermilion add one ounce of resin, and melt them together. Have ready the branches or twigs peeled and dried, and paint them over with this mixture while hot. The twigs being covered, hold them over a gentle fire, turning them round till they are perfectly covered and smooth. White coral may also be made with white lead, and black with lampblack, mixed with resin. When irregular branches are required, the sprays of an old black thorn are best adapted for the purpose; and for regular branches the young shoots of the elm are most suitable. Cinders, stones, or any other materials may be dipped into the mixture, and made to assume the appearance of coral .

William Owen RA (1769-1825) was an English portrait painter known for his portraits of society figures such as Pitt the Younger and George, Prince of Wales (later King George IV).

William Owen was born at 13 Broad Street, Ludlow, Shropshire in 1769 and was baptised on 3 November in Ludlow Parish Church. Owen's father, Jeremiah Owen, had trained for the church but instead chose to follow in his father's profession and took over the family barber shop which he later expanded into a stationary and bookshop. Owen found his talent at a young age, and would frequently be found sketching the scenery of his surrounding area, his first identifiable work being a drawing of Ludlow Castle, which is thought to have been given to Margaret Maskelyne, Lady Clive (1735-1817).

In 1786 Owen moved to London, where he was apprenticed to the coach painter Charles Cotton, RA (1728–1798).This position was most likely arranged by his uncle, who was butler to the scholar and art theorist Richard Payne Knight, who lived near Ludlow. It appears that Owen was drawn to figure painting from the outset, and after copying a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds of the much admired actress Mary Robinson (better known as 'Perdita'), he was sent on the recommendation of Reynolds to the Royal Academy Schools in 1791.

Portrait of a man

By 1794 Owen had moved out of his lodgings with Cotton on Gate Street and into a new to studio at No.211 Piccadilly where he remained for two years before moving to No.5 Coventry Street, Haymarket. It is whilst living here that he presumably came into contact with future wife Lener Leaf, whose father worked in Haymarket as a shoe maker.

By 1797 Owen was working as a studio assistant to John Hoppner, who by this point was struggling to keep up with the demand for copies of his portraits. Owen was clearly also experiencing some success in his own right, for in the same year he painted Lener, along with her younger sister, and exhibited the portrait at Somerset House – the then location of Royal Academy exhibitions, receiving a great deal of praise and encouragement. Owen married Lener later that year on 2 December and their son William was born soon after.

In 1800 Owen and his family moved to Pimlico, although choosing to maintain his recently acquired studio at No.51 Leicester Square, next door to the house in which Sir Joshua Reynolds lived. This remained Owen's studio until he became too ill and moved out in 1818. The year 1797/8 was perhaps the most significant in Owen's career as a painter; in 1797 he painted the then Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger which he exhibited the following year along with a portrait of the Lord Chancellor Alexander Wedderburn.

In 1810 following the death of John Hoppner (1758–1810), Owen was appointed portrait painter to the Prince of Wales, later George IV (1762–1830). Unfortunately the prince never gave a sitting and instead Owen had to rely on a number of head sketches by his predecessor Hoppner to create a likeness. In 1813 Owen was offered a knighthood however he declined.

In 1818 Owen left his house in Pimlico and his studio in Leicester Square and moved to Bruton Street, most probably due to his slowly decreasing health, his eagerness however remained unscathed and he exhibited eight works at the Royal Academy the following year. In 1819 Owen travelled to Bath to meet a respectable man of medicine named Mr Hicks, however this seemed to have no positive effect and he soon returned to London. By 1820 Owen was confined to his bed where, with the exception of a brief six months spent in Chelsea towards the end of 1824, he remained until his death five years later.

In 1825 Owen died after being accidentally poisoned by an overdose of 'Barclay's Drops' – a mixture of aniseed, camphor and opium. Owen was very ill at the time, being confined to his bedroom and unable to move his limbs, relying on a draught medicine to aid his recovery. When the draught ran out his cook was sent to fetch another bottle, along with a bottle of Barclay's Drops, however the chemist labelled the two bottles wrongly and as a result Owen took a fatal dose of the opium-based medicine, dying hours later. At the inquest on 13 March 1825 the following verdict was reached by the jury:

That the deceased, Mr. Wm. Owen, Esq,. died from taking a large quantity of Barclays drops; the bottle containing that liquid having been negligently and incautiously labelled, by the person who prepared the medicine as an opening draught, such as the said Mr. Owen had been in the habit of taking and that we understand the above lamented mistake took place at the house of Mr. Smith, a chymist and druggist in the Haymarket.

Owen was buried on 19 March 1825 at Saint Luke's, Chelsea, in a private ceremony attended by family and close friends, including Sir Thomas Lawrence, Sir Richard Westmacott, Thomas Phillips and 'Thompson' – most probably Thomas Clement Thompson.