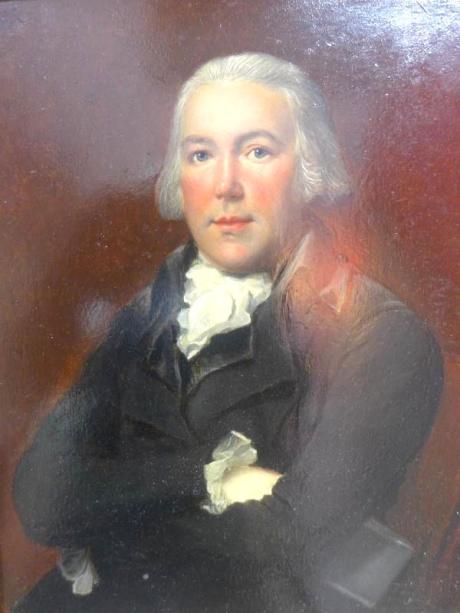

inscribed in sepia ink exetsively on the reverse "William Woodville, MD, FRS, FLS, /Physician to the Middlesex Hospital and Small Pox Hospital/ Born at Lowswaid 1752 dield in London 1805/ This portrait was the property of Dr Woodville's friend Dr Piel, and was bequeathed by him together with his own portrait to Joseph Steel esq of Cockermouth who's son Edward Steel presented it to William …….of Birkby

Dr Piel

Joseph Steel esq of Cockermouth

Edward Steel

William …….of Birkby

William Woodville, (1752–1805), physician and botanist, was born at Cockermouth in Cumberland, the fourth of the six children of William Woodville (1714–1758), and Jane Fearon (1723–1804). He came from a family of well-to-do Quakers, and was initially educated at a local grammar school. He began his medical training in 1767 with a short apprenticeship to William Birtwhistle, an apothecary. He later matriculated at Edinburgh University, graduating MD in 1775 with a thesis on irritable fibres. Woodville returned to Cumberland to practise in Papcastle, until a tragic incident in 1778 interrupted his career. One night he fired a gun through a window and killed a man who had been creating a disturbance in his garden. Although this was generally accepted as an accident, Woodville was disowned by his Quaker meeting and left the county to set up practice in Denbigh. By 1782 he had moved to London: there his career flourished. He was appointed physician to the Middlesex Dispensary, admitted as a licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians in August 1784, and became a member of the Physical Society at Guy's Hospital.

Woodville's medical career was distinguished by his contributions to the prevention of smallpox. In 1791 he was appointed physician to the London Smallpox and Inoculation Hospital at St Pancras, a charitable institution offering care to smallpox victims and free inoculation. Woodville became a staunch supporter of the procedure: in 1797 he published a pamphlet aimed at a popular audience, advocating inoculation. By this time he was also writing a major history of inoculation, probably intended as a triumphal history of the steady growth of the procedure, with an emphasis on the role of the hospital in encouraging inoculation and thus helping to control smallpox. The first of the projected two volumes of the History of the Inoculation of the Smallpox (1796) described inoculation techniques used in the Near East and the Far East, its introduction to Britain, and its gradual popularization up to 1770. However, history caught up with the project. In 1799 the second volume was announced as ready for the press but it never appeared, as the previous year Edward Jenner had announced his discovery of vaccination, which attracted considerable attention: although the older procedure was still widely used, the book would have lost much of its original purpose.

Woodville quickly switched his allegiance to vaccination and played an important role in establishing its merits. News of Jenner's discovery had aroused interest among medical men, but his source of vaccine had been lost and further experiments with the new procedure were therefore impossible. Woodville remedied this in January 1799, when he was told of an outbreak of cowpox in a London dairy. Having compared the lesions among the milkers with Jenner's illustration, Woodville took some fluid for use as vaccine at the Smallpox Hospital. The results of this action, the first large-scale trial of vaccination, were published as the Report of a Series of Inoculations for the Variolae vaccinae or Cow Pox (1799). Its case histories of two hundred vaccinations, most of which were subsequently tested by inoculation, did much to prove the efficacy of the new practice. However, the Report also cast the first doubts as to the merits of vaccination. Woodville noted that vaccination frequently produced smallpox-like eruptions which he believed might communicate smallpox. This undermined one of the principal advantages of the new practice over inoculation—patients did not have to be isolated. Woodville's observation sparked off a dispute between Woodville and Jenner. Jenner blamed Woodville's results on contaminated vaccine: Woodville responded with his Observations on Cow-Pox (1800) arguing that hybridization between cowpox and smallpox was impossible. Thereafter the dispute fizzled out, unresolved. Relations between the two pioneers were partially restored by mutual friends, particularly John Coakley Lettsom, but never became cordial, Jenner being suspicious of any potential rival to his authority as the leading expert on vaccination. Woodville continued to promote vaccination through his practice at the Smallpox Hospital, and later briefly held a post as vaccinator to the Royal Jennerian Society, a charity offering free vaccination. In 1800 he travelled to France to assist in the introduction of the procedure there.

Woodville had a deep interest in botany. He was elected to the Linnean Society in 1791, and maintained a botanic garden within the grounds of the Smallpox Hospital. Between 1790 and 1794 he published Medical Botany, a four-volume catalogue of plants, based on the pharmacopoeia of the royal colleges of physicians in London and Edinburgh. Each plant was described by both its botanical characteristics and its therapeutic uses, and illustrated with an engraving.

Woodville died on 26 March 1805 at the Smallpox Hospital, having been moved from his house in Ely Place, Holborn, at his special request. His cause of death is variously recorded as smallpox (which seems unlikely, given his constant exposure to infection), dropsy, and a chronic pulmonary complaint. Woodville received a Quaker funeral and was buried at Bunhill Fields on 4 April. His library was sold at Sothebys on 3 July 1805. Deborah Brunton DNB

Lemuel "Francis" Abbott (1760/61 – 5 December 1802) was an English portrait painter, famous for his likeness of Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson (currently hanging in the Terracotta Room of number 10 Downing Street) and for those of other naval officers and literary figures of the 18th century.

He was born Lemuel Abbott in Leicestershire in 1760 or 1761, the son of clergyman Lemuel Abbott, curate of Anstey (and later vicar of Thornton) and his wife Mary. In 1775, at the age of 14, he became a pupil of Francis Hayman and lived in London, but returned to his parents after his teacher's death in 1776. There he continued to develop his artistic talents independently, but some authorities have suggested that he may also have studied with Joseph Wright of Derby.

In 1780, Abbott married Anna Maria, and again settled in London, residing for many years in Caroline Street in Bloomsbury. Although he exhibited at the Royal Academy, he never became an Academician. It is said that overwork, due to the commissions he took on, and domestic unhappiness led to his becoming insane. He was declared insane in 1798 and was treated by Dr Thomas Munro (1759–1833), the chief physician to Bethlem Hospital and a specialist in mental disorders – Munro also treated King George III (1738–1820).

Abbott died in London on 5 December 1802. Abbott painted portraits of many figures of the day including leading seamen such as Admiral Nelson, Admiral Sir Robert Calder, Rear-Admiral Sir Thomas Pasley and Captain William Locker, astronomer Sir William Herschel, poet William Cowper, artists Francesco Bartolozziand Joseph Nollekens, entrepreneur Matthew Boulton and industrialist John Wilkinson amongst others. Some of his paintings were signed "Francis Lemuel Abbott", but it is not known why he assumed the additional Christian name, as it was not one with which he was baptised.