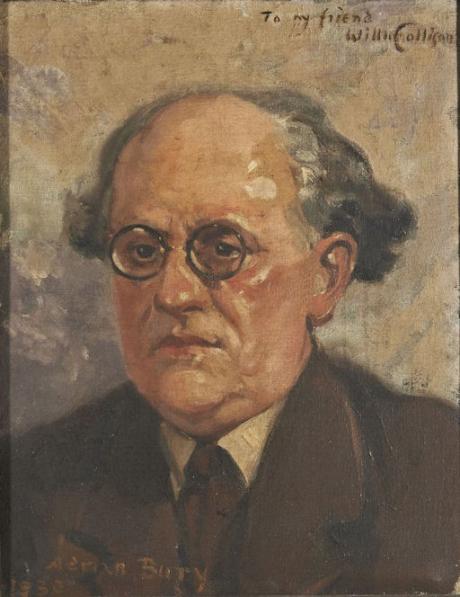

signed and inscribed and dated ""To My Friend/William Collison / 1930"

William Collison, (1865–1938), workers' leader, was born on 22 June 1865 at 22 Greenfield Street, Mile End, London, the eldest of twelve children of William Collison, policeman, and his wife, Leah (née Brett). Collison's formal education did not progress beyond elementary school; it must be presumed that his later fluency with the pen was the result of his own efforts at self-improvement. A long series of casual jobs, punctuated by a two-year period of service in the British army, took him into the world of London's dockland. His talents as an agitator and as an organizer soon became apparent. In 1886 he was elected as a delegate to the Mansion House Unemployed Relief Committee, where he was befriended by Cardinal Manning. Later he became a paid official of the Tramway and Omnibus Employees' Trade Union. Collison's early enthusiasm for trade unions began to wane. In 1890 he declined to support a strike called by the Tramway Union in protest against moves by the employers to counter dishonesty among their workers. He left the union, and attempted to obtain casual work again in the London docks, but was refused employment. This was because he was not a member of the dockers' trade union formed the previous year, when the great dock strike had marked the beginning of trade union organization (the so-called ‘new unionism’) among unskilled manual workers. Collison's anti-union views now took on a definite shape. He resented the manner in which (as he argued) professional socialists were exploiting the plight of the poor for their own political ends. The tactics of the closed shop, of which he now found himself a victim, were one of the hallmarks of new unionism; another was the use of the strike as a weapon of first rather than last resort. Collison regarded new unionism as a form of socialist tyranny, and he determined to fight it. He knew that there were many other like-minded members of the working classes who shared his views. On 16 May 1893, at Ye Olde Roebuck public house, Aldgate, he called a ‘General Conference of men interested in Free Labour’: this became the National Free Labour Association (NFLA). Collison hoped that the NFLA would become the free labour equivalent of the Trades Union Congress. The NFLA held annual conferences, open to the press and lavishly advertised. It is clear from revelations subsequently made by some of Collison's former associates that these annual gatherings were heavily stage-managed. But the Free Labour Gazette (later Free Labour Press) which the NFLA published between 1894 and 1907 was professionally produced, its editor from 1896 being John Charles Manning, an experienced journalist. Collison himself branched out into journalism of a sort: it was he who supplied The Times with the material used in the sensational series of attacks on trade union practices which appeared anonymously in that paper between 18 November 1901 and 16 January 1902. The ostensible purpose of the NFLA was to maintain a network of free labour exchanges, by means of which non-union labour might be supplied wherever it was needed. In practice, this network acted as the major supplier of blackleg labour to British industry in the period from the NFLA's foundation until the First World War. Most of Collison's interventions were small-scale; he could not hope to replace craftsmen, though the sight of his blacklegs, protected by the police, undoubtedly had an effect on the morale of strikers. In 1900, however, he scored a coup. Asked by the Taff Vale Railway Company to organize a supply of railwaymen to break a strike called by the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, Collison made certain that every free labourer had signed an agreement to enter into the service of the company, which was thus enabled to obtain damages from the railwaymen's union for inducing breaches of contract. The Taff Vale dispute established the principle that trade unions were liable to pay damages in respect of industrial action. The case convinced many trade unions, hitherto lukewarm in their response to the Labour Representation Committee (forerunner of the Labour Party), that they must now support it to obtain legislative reversal of the legal judgment. This was effected through the Trade Disputes Act of 1906, enacted by the incoming Liberal government. No less important was the reluctance of that Liberal administration to sanction the use of the police to protect blacklegs. More fundamentally, although it was the case that some groups of employers (most notoriously, the railway companies) undoubtedly shared Collison's anti-union sentiments, they were in a decided minority. Spurred by the Conciliation Act passed by the Unionist government in 1896, most large employers of labour had come to accept the reality of organized labour and to recognize the benefits and conveniences of collective bargaining. What most employers wanted, even in the 1890s, was conciliation, not the politics of confrontation which Collison offered them. Certainly after 1906 the political and industrial climates in which the NFLA had flourished rapidly disappeared. However, the organization continued to exist, certainly until 1929, operating from offices in the City of London. It is easy to dismiss Collison as a tool of those employers whose counter-offensive against new unionism was at its height in the period from 1890 to 1906. But the surviving archival evidence suggests otherwise. Collison was paid by employers, but mainly for services rendered. It seems safer to regard him as a particularly vivid example of working-class hostility to new unionism and to socialism at this time. An accomplished self-publicist, sporting curly hair, wide-brimmed hat, and bow-tie, Collison rubbed shoulders with the powerful but never forgot his proletarian origins. Practically nothing is known of his private life. He died at his home, 160 Eccleston Crescent, Ilford, on 8 March 1938, of heart disease, bronchitis, and emphysema; he was survived by a daughter, Emilie. Geoffrey Alderman

Artist and writer born in the London as Albert Buhrer, the son a Swiss born sculptor and bronze caster and a nephew of the sculptor Alfred Gilbert.