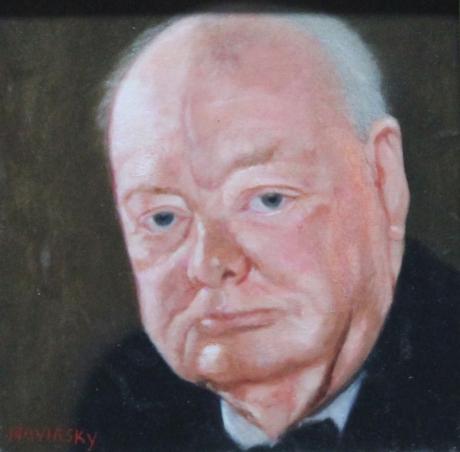

"NAVIASKY"

After a sensational rise to prominence in national politics before World War I, Churchill acquired a reputation for erratic judgment in the war itself and in the decade that followed. Politically suspect in consequence, he was a lonely figure until his response to Adolf Hitler’s challenge brought him to leadership of a national coalition in 1940. With Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin he then shaped Allied strategy in World War II, and after the breakdown of the alliance he alerted the West to the expansionist threat of the Soviet Union. He led theConservative Party back to office in 1951 and remained prime minister until 1955, when ill health forced his resignation.

In Churchill’s veins ran the blood of both of the English-speaking peoples whose unity, in peace and war, it was to be a constant purpose of his to promote. Through his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, the meteoric Tory politician, he was directly descended from John Churchill, 1st duke of Marlborough, the heroof the wars against Louis XIV of France in the early 18th century. His mother, Jennie Jerome, a noted beauty, was the daughter of a New York financier and horse racing enthusiast, Leonard W. Jerome.

The young Churchill passed an unhappy and sadly neglected childhood, redeemed only by the affection of Mrs. Everest, his devoted nurse. At Harrow his conspicuously poor academic record seemingly justified his father’s decision to enter him into an army career. It was only at the third attempt that he managed to pass the entrance examination to the Royal Military College, now Academy, Sandhurst, but, once there, he applied himself seriously and passed out (graduated) 20th in a class of 130. In 1895, the year of his father’s tragic death, he entered the 4th Hussars. Initially the only prospect of action was inCuba, where he spent a couple of months of leave reporting the Cuban war of independence from Spain for the Daily Graphic (London). In 1896 his regiment went to India, where he saw service as both soldier and journalist on the North-West Frontier (1897). Expanded as The Story of the Malakand Field Force (1898), his dispatches attracted such wide attention as to launch him on the career of authorship that he intermittently pursued throughout his life. In 1897–98 he wrote Savrola (1900), a Ruritanianromance, and got himself attached to Lord Kitchener’s Nile expeditionary force in the same dual role of soldier and correspondent. The River War (1899) brilliantly describes the campaign.

The five years after Sandhurst saw Churchill’s interests expand and mature. He relieved the tedium of army life in India by a program of reading designed to repair the deficiencies of Harrow and Sandhurst, and in 1899 he resigned his commission to enter politics and make a living by his pen. He first stood as a Conservative at Oldham, where he lost a by-election by a narrow margin, but found quick solace in reporting the South African War for The Morning Post (London). Within a month after his arrival inSouth Africa he had won fame for his part in rescuing an armoured train ambushed by Boers, though at the price of himself being taken prisoner. But this fame was redoubled when less than a month later he escaped from military prison. Returning to Britain a military hero, he laid siege again to Oldham in the election of 1900. Churchill succeeded in winning by a margin as narrow as that of his previous failure. But he was now in Parliament and, fortified by the £10,000 his writings and lecture tours had earned for him, was in a position to make his own way in politics.

A self-assurance redeemed from arrogance only by a kind of boyish charm made Churchill from the first a notable House of Commons figure, but a speech defect, which he never wholly lost, combined with a certain psychological inhibition to prevent him from immediately becoming a master of debate. He excelled in the set speech, on which he always spent enormous pains, rather than in the impromptu; Lord Balfour, the Conservative leader, said of him that he carried “heavy but not very mobile guns.” In matter as in style he modeled himself on his father, as his admirable biography, Lord Randolph Churchill (1906; revised edition 1952), makes evident, and from the first he wore his Toryism with a difference, advocating a fair, negotiated peace for the Boers and deploring military mismanagement and extravagance.

In 1904 the Conservative government found itself impaled on a dilemma by Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain’s open advocacy of a tariff. Churchill, a convinced free trader, helped to found the Free Food League. He was disavowed by his constituents and became increasingly alienated from his party. In 1904 he joined the Liberals and won renown for the audacity of his attacks on Chamberlain and Balfour. The radical elements in his political makeup came to the surface under the influence of two colleagues in particular, John Morley, a political legatee of W.E. Gladstone, and David Lloyd George, the rising Welsh orator and firebrand. In the ensuing general election in 1906 he secured a notable victory in Manchester and began his ministerial career in the new Liberal government as undersecretary of state for the colonies. He soon gained credit for his able defense of the policy of conciliation and self-government in South Africa. When the ministry was reconstructed under Prime Minister Herbert H. Asquith in 1908, Churchill was promoted to president of the Board of Trade, with a seat in the cabinet. Defeated at the ensuing by-election in Manchester, he won an election at Dundee. In the same year he married the beautiful Clementine Hozier; it was a marriage of unbroken affection that provided a secure and happy background for his turbulent career.

At the Board of Trade, Churchill emerged as a leader in the movement of Liberalism away from laissez-faire toward social reform. He completed the work begun by his predecessor, Lloyd George, on the bill imposing an eight-hour maximum day for miners. He himself was responsible for attacking the evils of “sweated” labour by setting up trade boards with power to fix minimum wages and for combating unemployment by instituting state-run labour exchanges.

When this Liberal program necessitated high taxation, which in turn provoked the House of Lords to the revolutionary step of rejecting the budget of 1909, Churchill was Lloyd George’s closest ally in developing the provocative strategy designed to clip the wings of the upper chamber. Churchill became president of the Budget League, and his oratorical broadsides at the House of Lords were as lively and devastating as Lloyd George’s own. Indeed Churchill, as an alleged traitor to his class, earned the lion’s share of Tory animosity. His campaigning in the two general elections of 1910 and in theHouse of Commons during the passage of the Parliament Act of 1911, which curbed the House of Lords’ powers, won him wide popular acclaim. In the cabinet his reward was promotion to the office of home secretary. Here, despite substantial achievements in prison reform, he had to devote himself principally to coping with a sweeping wave of industrial unrest and violent strikes. Upon occasion his relish for dramatic action led him beyond the limits of his proper role as the guarantor of public order. For this he paid a heavy price in incurring the long-standing suspicion of organized labour.

In 1911 the provocative German action in sending a gunboat to Agadir, the Moroccan port to whichFrance had claims, convinced Churchill that in any major Franco-German conflict Britain would have to be at France’s side. When transferred to the Admiralty in October 1911, he went to work with a conviction of the need to bring the navy to a pitch of instant readiness. His first task was the creation of a naval war staff. To help Britain’s lead over steadily mounting German naval power, Churchill successfully campaigned in the cabinet for the largest naval expenditure in British history. Despite his inherited Tory views on Ireland, he wholeheartedly embraced the Liberal policy of Home Rule, moving the second reading of the Irish Home Rule Bill of 1912 and campaigning for it in the teeth of Unionist opposition. Although, through his friendship with F.E. Smith (later 1st earl of Birkenhead) and Austen Chamberlain, he did much to arrange the compromise by which Ulster was to be excluded from the immediate effect of the bill, no member of the government was more bitterly abused—by Tories as a renegade and by extreme Home Rulers as a defector.

War came as no surprise to Churchill. He had already held a test naval mobilization. Of all the cabinet ministers he was the most insistent on the need to resist Germany. On August 2, 1914, on his own responsibility, he ordered the naval mobilization that guaranteed complete readiness when war was declared. The war called out all of Churchill’s energies. In October 1914, when Antwerp was falling, he characteristically rushed in person to organize its defense. When it fell the public saw only a disillusioning defeat, but in fact the prolongation of its resistance for almost a week enabled the Belgian Army to escape and the crucial Channel ports to be saved. At the Admiralty, Churchill’s partnership with Adm. Sir John Fisher, the first sea lord, was productive both of dynamism and of dissension. In 1915, when Churchill became an enthusiast for the Dardanelles expedition as a way out of the costly stalemate on the Western Front, he had to proceed against Fisher’s disapproval. The campaign aimed at forcing the straits and opening up direct communications with Russia. When the naval attack failed and was called off on the spot by Adm. J.M. de Robeck, the Admiralty war group and Asquith both supported de Robeck rather than Churchill. Churchill came under heavy political attack, which intensified when Fisher resigned. Preoccupied with departmental affairs, Churchill was quite unprepared for the storm that broke about his ears. He had no part at all in the maneuvers that produced the first coalition government and was powerless when the Conservatives, with the sole exception of Sir William Maxwell Aitken (soon Lord Beaverbrook), insisted on his being demoted from the Admiralty to the duchy of Lancaster. There he was given special responsibility for the Gallipoli Campaign (a land assault at the straits) without, however, any powers of direction. Reinforcements were too few and too late; the campaign failed and casualties were heavy; evacuation was ordered in the autumn.

In November 1915 Churchill resigned from the government and returned to soldiering, seeing active service in France as lieutenant colonel of the 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers. Although he entered the service with zest, army life did not give full scope for his talents. In June 1916, when his battalion was merged, he did not seek another command but instead returned to Parliament as a private member. He was not involved in the intrigues that led to the formation of a coalition government under Lloyd George, and it was not until 1917 that the Conservatives would consider his inclusion in the government. In March 1917 the publication of the Dardanelles commission report demonstrated that he was at least no more to blame for the fiasco than his colleagues.

Even so, Churchill’s appointment as minister of munitions in July 1917 was made in the face of a storm of Tory protest. Excluded from the cabinet, Churchill’s role was almost entirely administrative, but his dynamic energies thrown behind the development and production of the tank (which he had initiated at the Admiralty) greatly speeded up the use of the weapon that broke through the deadlock on the Western Front. Paradoxically, it was not until the war was over that Churchill returned to a service department. In January 1919 he became secretary of war. As such he presided with surprising zeal over the cutting of military expenditure. The major preoccupation of his tenure in the War Office was, however, the Allied intervention in Russia. Churchill, passionately anti-Bolshevik, secured from a divided and loosely organized cabinet an intensification and prolongation of the British involvement beyond the wishes of any major group in Parliament or the nation—and in the face of the bitter hostility of labour. And in 1920, after the last British forces had been withdrawn, Churchill was instrumental in having arms sent to the Poles when they invaded the Ukraine.

In 1921 Churchill moved to the Colonial Office, where his principal concern was with the mandated territories in the Middle East. For the costly British forces in the area he substituted a reliance on the air force and the establishment of rulers congenial to British interests; for this settlement of Arab affairs he relied heavily on the advice of T.E. Lawrence. For Palestine, where he inherited conflicting pledges to Jews and Arabs, he produced in 1922 the White Paper that confirmed Palestine as a Jewish national home while recognizing continuing Arab rights. Churchill never had departmental responsibility for Ireland, but he progressed from an initial belief in firm, even ruthless, maintenance of British rule to an active role in the negotiations that led to the Irish treaty of 1921. Subsequently, he gave full support to the new Irish government.

In the autumn of 1922 the insurgent Turks appeared to be moving toward a forcible reoccupation of the Dardanelles neutral zone, which was protected by a small British force at Chanak (now Çanakkale). Churchill was foremost in urging a firm stand against them, but the handling of the issue by the cabinet gave the public impression that a major war was being risked for an inadequate cause and on insufficient consideration. A political debacle ensued that brought the shaky coalition government down in ruins, with Churchill as one of the worst casualties. Gripped by a sudden attack of appendicitis, he was not able to appear in public until two days before the election, and then only in a wheelchair. He was defeated humiliatingly by more than 10,000 votes. He thus found himself, as he said, all at once “without an office, without a seat, without a party, and even without an appendix.”

In convalescence and political impotence Churchill turned to his brush and his pen. His painting never rose above the level of a gifted amateur’s, but his writing once again provided him with the financial base his independent brand of politics required. His autobiographical history of the war, The World Crisis, netted him the £20,000 with which he purchased Chartwell, henceforth his country home in Kent. When he returned to politics it was as a crusading anti-Socialist, but in 1923, when Stanley Baldwin was leading the Conservatives on a protectionist program, Churchill stood, at Leicester, as a Liberal free trader. He lost by approximately 4,000 votes. Asquith’s decision in 1924 to support a minority Labour government moved Churchill farther to the right. He stood as an “Independent Anti-Socialist” in a by-election in the Abbey division of Westminster. Although opposed by an official Conservative candidate—who defeated him by a hairbreadth of 43 votes—Churchill managed to avoid alienating the Conservative leadership and indeed won conspicuous support from many prominent figures in the party. In the general election in November 1924 he won an easy victory at Epping under the thinly disguised Conservative label of “Constitutionalist.” Baldwin, free of his flirtation with protectionism, offered Churchill, the “constitutionalist free trader,” the post of chancellor of the Exchequer. Surprised, Churchill accepted; dumbfounded, the country interpreted it as a move to absorb into the party all the right-of-centre elements of the former coalition.

In the five years that followed, Churchill’s early liberalism survived only in the form of advocacy of aissez-faire economics; for the rest he appeared, repeatedly, as the leader of the diehards. He had no natural gift for financial administration, and though the noted economist John Maynard Keynescriticized him unsparingly, most of the advice he received was orthodox and harmful. His first move was to restore the gold standard, a disastrous measure, from which flowed deflation, unemployment, and the miners’ strike that led to the general strike of 1926. Churchill offered no remedy except the cultivation of strict economy, extending even to the armed services. Churchill viewed the general strike as a quasi-revolutionary measure and was foremost in resisting a negotiated settlement. He leaped at the opportunity of editing the British Gazette, an emergency official newspaper, which he filled with bombastic and frequently inflammatory propaganda. The one relic of his earlier radicalism was his partnership with Neville Chamberlain as minister of health in the cautious expansion of social services, mainly in the provision of widows’ pensions.

In 1929, when the government fell, Churchill, who would have liked a Tory-Liberal reunion, deplored Baldwin’s decision to accept a minority Labour government. The next year an open rift developed between the two men. On Baldwin’s endorsement of a Round Table Conference with Indian leaders, Churchill resigned from the shadow cabinet and threw himself into a passionate, at times almost hysterical, campaign against the Government of India bill (1935) designed to give India dominion status.

Thus, when in 1931 the National Government was formed, Churchill, though a supporter, had no hand in its establishment or place in its councils. He had arrived at a point where, for all his abilities, he was distrusted by every party. He was thought to lack judgment and stability and was regarded as a guerrilla fighter impatient of discipline. He was considered a clever man who associated too much with clever men—Birkenhead, Beaverbrook, Lloyd George—and who despised the necessary humdrum associations and compromises of practical politics.

In this situation he found relief, as well as profit, in his pen, writing, in Marlborough: His Life and Times, a massive rehabilitation of his ancestor against the criticisms of the 19th-century historian Thomas Babington Macaulay. But overriding the past and transcending his worries about India was a mounting anxiety about the growing menace of Hitler’s Germany. Before a supine government and a doubting opposition, Churchill persistently argued the case for taking the German threat seriously and for the need to prevent the Luftwaffe from securing parity with the Royal Air Force. In this he was supported by a small but devoted personal following, in particular the gifted, curmudgeonly Oxford physics professor Frederick A. Lindemann (later Lord Cherwell), who enabled him to build up at Chartwell a private intelligence centre the information of which was often superior to that of the government. When Baldwin became prime minister in 1935, he persisted in excluding Churchill from office but gave him the exceptional privilege of membership in the secret committee on air-defense research, thus enabling him to work on some vital national problems. But Churchill had little success in his efforts to impart urgency to Baldwin’s administration. The crisis that developed when Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935 found Churchill ill prepared, divided between a desire to build up the League of Nations around the concept of collective security and the fear that collective action would drive Benito Mussolini into the arms of Hitler. The Spanish Civil War (1936–39) found him convinced of the virtues of nonintervention, first as a supporter and later as a critic of Francisco Franco. Such vagaries of judgment in fact reflected the overwhelming priority he accorded to one issue—the containment of German aggressiveness. At home there was one grievous, characteristic, romantic misreading of the political and public mood, when, in Edward VIII’s abdication crisis of 1936, he vainly opposed Baldwin by a public championing of the King’s cause.

When Neville Chamberlain succeeded Baldwin, the gulf between the Cassandra-like Churchill and the Conservative leaders widened. Repeatedly the accuracy of Churchill’s information on Germany’s aggressive plans and progress was confirmed by events; repeatedly his warnings were ignored. Yet his handful of followers remained small; politically, Chamberlain felt secure in ignoring them. As German pressure mounted on Czechoslovakia, Churchill without success urged the government to effect a joint declaration of purpose by Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. When the Munich Agreementwith Hitler was made in September 1938, sacrificing Czechoslovakia to the Nazis, Churchill laid bare its implications, insisting that it represented “a total and unmitigated defeat.” In March 1939 Churchill and his group pressed for a truly national coalition, and, at last, sentiment in the country, recognizing him as the nation’s spokesman, began to agitate for his return to office. As long as peace lasted, Chamberlain ignored all such persuasions.

In a sense, the whole of Churchill’s previous career had been a preparation for wartime leadership. An intense patriot; a romantic believer in his country’s greatness and its historic role in Europe, the empire, and the world; a devotee of action who thrived on challenge and crisis; a student, historian, and veteran of war; a statesman who was master of the arts of politics, despite or because of long political exile; a man of iron constitution, inexhaustible energy, and total concentration, he seemed to have been nursing all his faculties so that when the moment came he could lavish them on the salvation of Britain and the values he believed Britain stood for in the world.

On September 3, 1939, the day Britain declared war on Germany, Chamberlain appointed Churchill to his old post in charge of the Admiralty. The signal went out to the fleet: “Winston is back.” On September 11 Churchill received a congratulatory note from Pres.Franklin D. Roosevelt and replied over the signature “Naval Person”; a memorable correspondence had begun. At once Churchill’s restless energy began to be felt throughout the administration, as his ministerial colleagues as well as his own department received the first of those pungent minutes that kept the remotest corners of British wartime government aware that their shortcomings were liable to detection and penalty. All his efforts, however, failed to energize the torpid Anglo-French entente during the so-called “phony war,” the period of stagnation in the European war before the German seizure of Norway in April 1940. The failure of the Narvik and Trondheim expeditions, dependent as they were on naval support, could not but evoke some memories of the Dardanelles and Gallipoli, so fateful for Churchill’s reputation in World War I. This time, however, it was Chamberlain who was blamed, and it was Churchill who endeavoured to defend him.

The German invasion of the Low Countries, on May 10, 1940, came like a hammer blow on top of the Norwegian fiasco. Chamberlain resigned. He wanted Lord Halifax, the foreign secretary, to succeed him, but Halifax wisely declined. It was obvious that Churchill alone could unite and lead the nation, since the Labour Party, for all its old distrust of Churchill’s anti-Socialism, recognized the depth of his commitment to the defeat of Hitler. A coalition government was formed that included all elements save the far left and right. It was headed by a war cabinet of five, which included at first both Chamberlain and Halifax—a wise but also magnanimous recognition of the numerical strength of Chamberlainite conservatism—and two Labour leaders, Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood. The appointment of Ernest Bevin, a tough trade-union leader, as minister of labour guaranteed cooperation on this vital front. Offers were made to Lloyd George, but he declined them. Churchill himself took, in addition to the leadership of the House of Commons, the Ministry of Defence. The pattern thus set was maintained throughout the war despite many changes of personnel. The cabinet became an agency of swift decision, and the government that it controlled remained representative of all groups and parties. The Prime Minister concentrated on the actual conduct of the war. He delegated freely but also probed and interfered continuously, regarding nothing as too large or too small for his attention. The main function of the chiefs of the armed services became that of containing his great dynamism, as a governor regulates a powerful machine; but, though he prodded and pressed them continuously, he never went against their collective judgment. In all this, Parliament played a vital part. If World War II was strikingly free from the domestic political intrigues of World War I, it was in part because Churchill, while he always dominated Parliament, never neglected it or took it for granted. For him, Parliament was an instrument of public persuasion on which he played like a master and from which he drew strength and comfort.

On May 13 Churchill faced the House of Commons for the first time as prime minister. He warned members of the hard road ahead—“I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat”—and committed himself and the nation to all-out war until victory was achieved. Behind this simplicity of aim lay an elaborate strategy to which he adhered with remarkable consistency throughout the war. Hitler’s Germany was the enemy; nothing should distract the entire British people from the task of effecting its defeat. Anyone who shared this goal, even a Communist, was an acceptable ally. The indispensable ally in this endeavour, whether formally at war or not, was the United States. The cultivation and maintenance of its support was a central principle of Churchill’s thought. Yet whether the United States became a belligerent partner or not, the war must be won without a repetition for Britain of the catastrophic bloodlettings of World War I; and Europe at the conflict’s end must be reestablished as a viable, self-determining entity, while the Commonwealth should remain as a continuing, if changing, expression of Britain’s world role. Provided these essentials were preserved, Churchill, for all his sense of history, was surprisingly willing to sacrifice any national shibboleths—of orthodox economics, of social convention, of military etiquette or tradition—on the altar of victory. Thus, within a couple of weeks of this crusading anti-Socialist’s assuming power, Parliament passed legislation placing all “persons, their services and their property at the disposal of the Crown”—granting the government in effect the most sweeping emergency powers in modern British history.

The effort was designed to match the gravity of the hour. After the Allied defeat and the evacuation of the battered British forces from Dunkirk, Churchill warned Parliament that invasion was a real risk to be met with total and confident defiance. Faced with the swift collapse of France, Churchill made repeated personal visits to the French government in an attempt to keep France in the war, culminating in the celebrated offer of Anglo-French union on June 16, 1940. When all this failed, the Battle of Britainbegan on July 10. Here Churchill was in his element, in the firing line—at fighter headquarters, inspecting coast defenses or antiaircraft batteries, visiting scenes of bomb damage or victims of the “blitz,” smoking his cigar, giving his V sign, or broadcasting frank reports to the nation, laced with touches of grim Churchillian humour and splashed with Churchillian rhetoric. The nation took him to its heart; he and they were one in “their finest hour.”

Other painful and more debatable decisions fell to Churchill. The French fleet was attacked to prevent its surrender intact to Hitler. A heavy commitment was made to the concentrated bombing of Germany. At the height of the invasion threat, a decision was made to reinforce British strength in the eastern Mediterranean. Forces were also sent to Greece, a costly sacrifice; the evacuation of Crete looked like another Gallipoli, and Churchill came under heavy fire in Parliament.

In these hard days the exchange of U.S. overage destroyers for British Caribbean bases and the response, by way of lend-lease, to Churchill’s boast “Give us the tools and we’ll finish the job” were especially heartening to one who believed in a “mixing-up” of the English-speaking democracies. The unspoken alliance was further cemented in August 1941 by the dramatic meeting between Churchill and Roosevelt in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, which produced the Atlantic Charter, a statement of common principles between the United States and Britain.

When Hitler launched his sudden attack on the Soviet Union, Churchill’s response was swift and unequivocal. In a broadcast on June 22, 1941, while refusing to “unsay” any of his earlier criticisms ofCommunism, he insisted that “the Russian danger…is our danger” and pledged aid to the Russian people. Henceforth, it was his policy to construct a “grand alliance” incorporating the Soviet Union and the United States. But it took until May 1942 to negotiate a 20-year Anglo-Soviet pact of mutual assistance.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941) altered, in Churchill’s eyes, the whole prospect of the war. He went at once toWashington, D.C., and, with Roosevelt, hammered out a set of Anglo-American accords: the pooling of both countries’ military and economic resources under combined boards and a combined chiefs of staff; the establishment of unity of command in all theatres of war; and agreement on the basic strategy that the defeat of Germany should have priority over the defeat of Japan. The grand alliance had now come into being. Churchill could claim to be its principal architect. Safeguarding it was the primary concern of his next three and a half years.

In protecting the alliance, the respect and affection between him and Roosevelt were of crucial importance. They alone enabled Churchill, in the face of relentless pressure from Stalin and ardent advocacy by the U.S. chiefs of staff, to secure the rejection of the “second front” in 1942, a project he regarded as premature and costly. In August 1942 Churchill himself flew to Moscow to advise Stalin of the decision and to bear the brunt of his displeasure. At home, too, he came under fire in 1942: first in January after the reverses in Malaya and the Far East and later in June when Tobruk in North Africa fell to the Germans, but on neither occasion did his critics muster serious support in Parliament. The year 1942 saw some reconstruction of the cabinet in a “leftward” direction, which was reflected in the adoption in 1943 of Lord Beveridge’s plan for comprehensive social insurance, endorsed by Churchill as a logical extension of the Liberal reforms of 1911.

The Allied landings in North Africa necessitated a fresh meeting between Churchill and Roosevelt, this time in Casablanca in January 1943. There Churchill argued for an early, full-scale attack on “the under-belly of the Axis” but won only a grudging acquiescence from the Americans. There too was evolved the “unconditional surrender” formula of debatable wisdom. Churchill paid the price for his intensive travel (including Tripoli, Turkey, and Algeria) by an attack of pneumonia, for which, however, he allowed only the briefest of respites. In May he was in Washington again, arguing against persistent American aversion to his “under-belly” strategy; in August he was at Quebec, working out the plans for Operation Overlord, the cross-Channel assault. When he learned that the Americans were planning a large-scale invasion of Burma in 1944, his fears that their joint resources would not be adequate for a successful invasion of Normandy were revived. In November 1943 at Cairo he urged on Roosevelt priority for further Mediterranean offensives, but at Tehrān in the first “Big Three” meeting, he failed to retain Roosevelt’s adherence to a completely united Anglo-American front. Roosevelt, though he consulted in private with Stalin, refused to see Churchill alone; for all their friendship there was also an element of rivalry between the two Western leaders that Stalin skillfully exploited. On the issue of Allied offensive drives into southern Europe, Churchill was outvoted. Throughout the meetings Churchill had been unwell, and on his way home he came down again with pneumonia. Though recovery was rapid, it was mid-January 1944 before convalescence was complete. By May he was proposing to watch the D-Day assaults from a battle cruiser; only the King’s personal plea dissuaded him.

e on military success did not, for Churchill, mean indifference to its political implications. After the Quebec conference in September 1944, he flew to Moscow to try to conciliate the Russians and the Poles and to get an agreed division of spheres of influence in the Balkans that would protect as much of them as possible from Communism. In Greecehe used British forces to thwart a Communist takeover and at Christmas flew to Athens to effect a settlement. Much of what passed at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, including the Far East settlement, concerned only Roosevelt and Stalin, and Churchill did not interfere. He fought to save the Poles but saw clearly enough that there was no way to force the Soviets to keep their promises. Realizing this, he urged the United States to allow the Allied forces to thrust as far into eastern Europe as possible before the Russian armies should fill the vacuum left by German power, but he could not win over Roosevelt, Vice Pres. Harry S. Truman, or their generals to his views. He went toPotsdam in July in a worried mood. But in the final decisions of the conference he had no part; halfway through, when news came of his government’s defeat in parliamentary elections, he had to return to England and tender his resignation.

Already in 1944, with victory in prospect, party politics had revived, and by May 1945 all parties in the wartime coalition wanted an early election. But whereas Churchill wanted the coalition to continue at least until Japan was defeated, Labour wished to resume its independence. Churchill as the popular architect of victory seemed unbeatable, but as an election campaigner he proved to be his own worst enemy, indulging, seemingly at Beaverbrook’s urging, in extravagant prophecies of the appalling consequences of a Labour victory and identifying himself wholly with the Conservative cause. His campaign tours were a triumphal progress, but it was the war leader, not the party leader, whom the crowds cheered. Labour’s careful but sweeping program of economic and social reform was a better match for the nation’s mood than Churchill’s flamboyance. Though personally victorious at his Essex constituency of Woodford, Churchill saw his party reduced to 213 seats in a Parliament of 640.

The shock of rejection by the nation fell heavily on Churchill. Indeed, though he accepted the role of leader of the parliamentary opposition, he was never wholly at home in it. The economic and social questions that dominated domestic politics were not at the centre of his interests. Nor, with his imperial vision, could he approve of what he called Labour’s policy of “scuttle,” as evidenced in the granting of independence to India and Burma (though he did not vote against the necessary legislation). But in foreign policy a broad identity of view persisted between the front benches, and this was the area to which Churchill primarily devoted himself. On March 5, 1946, atFulton, Mo., he enunciated, in the presence of President Truman, the two central themes of his postwar view of the world: the need for Britain and the United States to unite as guardians of the peace against the menace of Soviet Communism, which had brought down an “iron curtain” across the face of Europe; and with equal fervour he emerged as an advocate of European union. At Zürich, on September 19, 1946, he urged the formation of “a council of Europe” and himself attended the first assembly of the council at Strasbourg in 1949. Meanwhile, he busied himself with his great history, The Second World War, six volumes (1948–53).

The general election of February 1950 afforded Churchill an opportunity to seek again a personal mandate. He abstained from the extravagances of 1945 and campaigned with his party rather than above it.

The electoral onslaught shook Labour but left them still in office. It took what Churchill called “one more heave” to defeat them in a second election, in October 1951. Churchill again took a vigorous lead in the campaign. He pressed the government particularly hard on its handling of the crisis caused by Iran’s nationalization of British oil companies and in return had to withstand charges of warmongering. The Conservatives were returned with a narrow majority of 26, and Churchill became prime minister for the second time. He formed a government in which the more liberal Conservatives predominated, though the Liberal Party itself declined Churchill’s suggestion of office. A prominent figure in the government was R.A. Butler, the progressive-minded chancellor of the Exchequer. Anthony Eden was foreign secretary. Some notable Churchillians were included, among them Lord Cherwell, who, as paymaster general, was principal scientific adviser with special responsibilities for atomic research and development.

The domestic labours and battles of his administration were far from Churchill’s main concerns. Derationing, decontrolling, rehousing, safeguarding the precarious balance of payments—these were relatively noncontroversial policies; only the return of nationalized steel and road transport to private hands aroused excitement. Critics sometimes complained of a lack of prime ministerial direction in these areas and, indeed, of a certain slackness in the reins of government. Undoubtedly Churchill was getting older and reserving more and more of his energies for what he regarded as the supreme issues, peace and war. He was convinced that Labour had allowed the transatlantic relationship to sag, and one of his first acts was to visit Washington (and also Ottawa) in January 1952 to repair the damage he felt had been done. The visit helped to check U.S. fears that the British would desert the Korean War, harmonized attitudes toward German rearmament and, distasteful though it was to Churchill, resulted in the acceptance of a U.S. naval commander in chief of the eastern Atlantic. It did not produce that sharing of secrets of atom bomb manufacture that Churchill felt had unfairly lapsed after the war. To the disappointment of many, Churchill’s advocacy of European union did not result in active British participation; his government confined itself to endorsement from the sidelines, though in 1954, faced with the collapse of the European Defense Community, Churchill and Eden came forward with a pledge to maintain British troops on the Continent for as long as necessary.

The year 1953 was in many respects a gratifying one for Churchill. It brought the coronation of QueenElizabeth II, which drew out all his love of the historic and symbolic. He personally received two notable distinctions, the Order of the Garter and the Nobel Prize for Literature. However, his hopes for a revitalized “special relationship” with Pres. Dwight D. Eisenhower during his tenure in the White House, beginning in 1953, were largely frustrated. A sudden stroke in June, which caused partial paralysis, obliged Churchill to cancel a planned Bermuda meeting at which he hoped to secure Eisenhower’s agreement to summit talks with the Russians. By October, Churchill had made a remarkable recovery and the meeting was held in December. But it did not yield results commensurate with Churchill’s hopes. The two leaders, for all their amity, were not the men they once were; their subordinates, John Foster Dulles and Anthony Eden, were antipathetic; and, above all, the role and status of each country had changed. In relation to the Far East in particular there was a persistent failure to see eye to eye. Though Churchill and Eden visited Washington, D.C., in June 1954 in hopes of securing U.S. acceptance of the Geneva Accords designed to bring an end to the war in Indochina, their success was limited. Over Egypt, however, Churchill’s conversion to an agreement permitting a phased withdrawal of British troops from the Suez base won Eisenhower’s endorsement and encouraged hopes, illusory as it subsequently appeared, of good Anglo-American cooperation in this area. In 1955, “arming to parley,” Churchill authorized the manufacture of a British hydrogen bomb while still striving for a summit conference. Age, however, robbed him of this last triumph. His powers were too visibly failing. His 80th birthday, on November 30, 1954, had been the occasion of a unique all-party ceremony of tribute and affection in Westminster Hall. But the tribute implied a pervasive assumption that he would soon retire. On April 5, 1955, his resignation took place, only a few weeks before his chosen successor, Sir Anthony Eden, announced plans for a four-power conference at Geneva.

Although Churchill laid down the burdens of office amid the plaudits of the nation and the world, he remained in the House of Commons (declining a peerage) to become “father of the house” and even, in 1959, to fight and win yet another election. He also published another major work, A History of the English- Speaking Peoples, four volumes (1956–58). But his health declined, and his public appearances became rare. On April 9, 1963, he was accorded the unique distinction of having an honorary U.S. citizenship conferred on him by an act of Congress. His death at his London home in January 1965 was followed by a state funeral at which almost the whole world paid tribute. He was buried in the family grave in Bladon churchyard, Oxfordshire.

In any age and time a man of Churchill’s force and talents would have left his mark on events and society. A gifted journalist, a biographer and historian of classic proportions, an amateur painter of talent, an orator of rare power, a soldier of courage and distinction, Churchill, by any standards, was a man of rare versatility. But it was as a public figure that he excelled. His experience of office was second only to Gladstone’s, and his gifts as a parliamentarian hardly less, but it was as a wartime leader that he left his indelible imprint on the history of Britain and on the world. In this capacity, at the peak of his powers, he united in a harmonious whole his liberal convictions about social reform, his deep conservative devotion to the legacy of his nation’s history, his unshakable resistance to tyranny from the right or from the left, and his capacity to look beyond Britain to the larger Atlantic community and the ultimate unity of Europe. A romantic, he was also a realist, with an exceptional sensitivity to tactical considerations at the same time as he unswervingly adhered to his strategical objectives. A fervent patriot, he was also a citizen of the world. An indomitable fighter, he was a generous victor. Even in the transition from war to peace, a phase in which other leaders have often stumbled, he revealed, at an advanced age, a capacity to learn and to adjust that was in many respects superior to that of his younger colleagues.

Philip Naviasky painted a number of portraits and he showed regulalry at the Royal Society Of Portrait Painters annual exhibition, among his portraits were Lord Nuffiled the Industrialist, the Politicians Ramsay Macdonald and Philip Snowden , Alderman David Beevers, Lord Mayor of Leeds, John Henry Green the English physician and philanthropist and stylistically similar to the portrait of churchill he also painted many Dales Characters and members of the Jewish community. This portrait was painted in the 1960 the decade which saw Naviasky's eye sight beging to fail and culminated in him stopping painting in the late 1960's.

Philip Naviasky (1894-1983 was a Leeds-based artist. Born to Polish-Jewish immigrant parents in 1894, he won a scholarship to the Leeds School of Fine Arts in 1907. In 1912, he was the youngest ever student accepted into the Royal Academy school at the age of 18. He went on to win a Royal Exhibition award and to study at the Royal College of Art, after which he spent his career in Leeds as an artist and art teacher at Leeds College of Art. He married Millie Astrinsky, the tailoress daughter of Lithuanian immigrants to Leeds, at the city’s New Central Synagogue in 1933. The couple had a daughter, Sonia, in 1934, who sometimes features in Naviasky’s portraits, and who became an artist in her own right.He was a fluent artist who worked widely in Yorkshire as well as abroad in Spai and south of France, Morocco and elsewhere. He showed at the RA, RP, RSA and had a series of solo shows. Galleries in Leeds, Newcastle, Preston and Stoke on Trent hold his works.

Naviasky’s decision to work in Yorkshire is perhaps responsible for his slow emergence to the rank of greatness, for, undeniably, artists working in London such as Augustus John (1878-1961) by this point held a dominating position in the market for portraiture. That is not to say however that Yorkshire didn’t also embrace and encourage the arts and Naviasky, along with several other contemporaries, benefitted greatly from a number of key and influential patrons connected to industry.