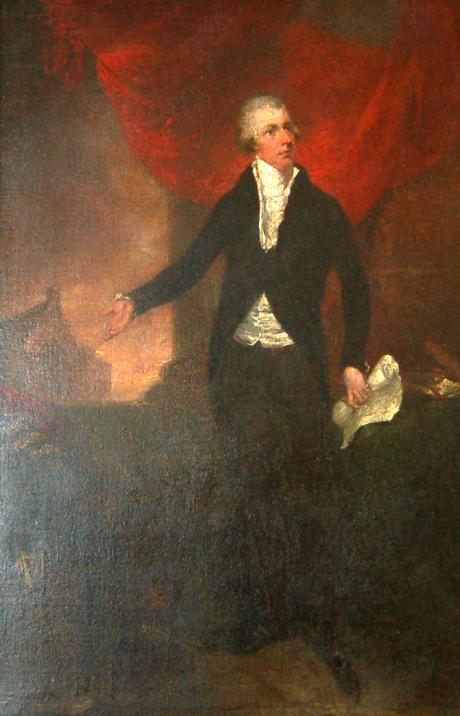

Engraved 1st Sept 1799, Mezzotint by Samuel William Reynolds 1773-1835, published by Jeffreys and Co.

William Pitt was born at Hayes, Kent on 28th May 1759. He suffered from poor health and was educated at home. His father, William Pitt, Earl of Chatham, was the former M.P. for Old Sarum and one of the most important politicians of the period. The Earl of Chatham was determined that his son would eventually become a member of the House of Commons and at an early age William was given lessons on how to become an effective orator. When William was fourteen he was sent to Pembroke Hall, Cambridge. His health remained poor and he spent most of the time with his tutor, the Rev. George Pretyman. William, who studied Latin and Greek, received his M.A. in 1776. William grew up with a strong interest in politics and spent much of his spare time watching debates in parliament. On 7th April 1778 he was present when his father collapsed while making a speech in the House of Lords and helped to carry his dying father from the chamber. In 1781 Sir James Lowther arranged for William Pitt to become the M.P. for Appleby. He made his first speech in the House of Commons on 26th February, 1781.

William Pitt had been well trained and afterwards, Lord North, the prime minister, described it as the "best speech" that he had ever heard. Soon after entering the Commons, William Pitt came under the influence of Charles Fox, Britain's leading Whig politician. Pitt joined Fox in his campaign for peace with the American colonies. On 12th June he made a speech where Pitt insisted that this was an "unjust war" and urged Lord North's government to bring it to an end.

Pitt also took an interest in the way that Britain elected Members of Parliament. He was especially critical of the way that the monarchy used the system to influence those in Parliament. Pitt argued that parliamentary reform was necessary for the preservation of liberty.

In June 1782 Pitt supported a motion for shortening the duration of parliament and for measures that would reduce the chances of government ministers being bribed. When Lord Frederick North's government fell in March 1782, Charles Fox became Foreign Secretary in Rockingham's Whig government. Fox left the government in July 1782, as he was unwilling to serve under the new prime minister, Lord Sherburne. Short of people willing to serve him, Sherburne appointed the twenty-three year old Pitt as his Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Fox interpreted Pitt's acceptance of this post as a betrayal and after this the two men became bitter enemies. On the 31st March, 1783, Pitt resigned and declared that he was "unconnected with any party whatever". Now out of power, Pitt turned his attention once more to parliamentary reform. On 7th May he proposed a plan that

included: (1) checking bribery at elections; (2) disfranchising corrupt constituencies; (3) adding to the number of members for London. His proposals were defeated by 293 to 149. Another bill that he introduced on 2nd June for restricting abuses in public office was passed by the House of Commons but rejected by the House of Lords. In Parliament he opposed Charles Fox's India Bill. Fox responded by making fun of Pitt's youth and inexperience and accusing him of following "the headlong course of ambition". George III was furious when the India Bill was passed by the House of Commons. The king warned members of the House of Lords that he would regard any one who voted for the bill as his enemy. Unwilling to upset the king, the Lords rejected the bill by 95 votes to 76.

The Duke of Portland's administration resigned and on 19th December, 1783, the king invited William Pitt to form a new government. At the age of only twenty-four, Pitt became Britain's youngest prime minister. When it was announced that Pitt had accepted the king's invitation, the news was received in the House of Commons with derisive laughter. Pitt had great difficulty finding enough people to join his government. Except for himself, his cabinet of seven contained no members of the House of Commons. Charles Fox led the attack on Pitt and although defeated in votes several times in the Commons, he refused to resign. After building up his popularity in the country, Pitt called a general election on 24th March, 1784.

Pitt's timing was perfect and 160 of Fox's supporters were defeated at the polls. Pitt himself stood for the seat of Cambridge University. Pitt now had a majority in the House of Commons and was able to persuade parliament to pass a series of measures including the India Act that established dual control of the East India Company. Pitt also attacked the serious problem of smuggling by reducing duties on those goods that were mainly being imported illegally into Britain. The success of this measure established his reputation as a shrewd politician.

In April 1785 Pitt proposed a bill that would bring an end to thirty-six rotten boroughs and to transfer the seventy-two seats to those areas where the population was growing. Although Pitt spoke in favour of reform, he refused to warn the House of Commons that he would resign if the measure was defeated. The Commons came to the conclusion that Pitt did not feel strongly about reform and when the vote was taken it was defeated by 248 votes to 174. Pitt accepted the decision of the Commons and never made another attempt to introduce parliamentary reform. The general election of October 1790 gave Pitt's government an increased majority. For the next few years Pitt was occupied with Britain's relationship with France. Pitt had initially viewed the French Revolution as a domestic issue which did not concern Britain. However, Pitt became worried when parliamentary reform groups in Britain appeared to be in contact with French revolutionaries. Pitt responded by issuing a proclamation against seditious writings.When Pitt heard that King Louis XVI had been executed in January 1793, he expelled the French Ambassador. In the House of Common's Charles Fox and his small group of supporters attacked Pitt for not doing enough to preserve peace with France. Fox therefore blamed Pitt when France declared war on Britain on 1st February, 1793.

Pitt's attitude towards political reform changed dramatically after war was declared. In May 1793 Pitt brought in a bill suspending Habeas Corpus. Although denounced by Charles Fox and his supporters, the bill was passed by the House of Commons in twenty-four hours.

Those advocating parliamentary reform were arrested and charged with sedition. Tom Paine managed to escape but others such as Thomas Hardy, John Thellwall and Thomas Muir were imprisoned. Pitt decided to form a great European coalition against France and between March and October 1793 he concluded alliances with Russia, Prussia, Austria, Spain, Portugal and some German princes. At first these tactics were successful but during 1794 Britain and her allies suffered a series of defeats. To pay for the war, Pitt was forced to increase taxation and to raise a loan of £18 million. This problem was made worse by a series of bad harvests. When going to open parliament in October 1795, George III was greeted with cries of 'Bread', 'Peace' and 'no Pitt'. Missiles were also thrown and so Pitt immediately decided to pass a new Sedition Bill that redefined the law of treason. Britain's continuing financial difficulties convinced Pitt to seek peace with France. These peace proposals were rejected by the French in May 1796 and William Pitt once again had to introduce new taxes. This included duties on horses and tobacco. The following year Pitt introduced additional taxes on tea, sugar and spirits. Even so, by November 1797, Britain had a budget deficit of

£22 million. On several occasions Pitt was in physical danger from angry mobs and he had to be constantly protected by an armed guard.

Pitt's health began to deteriorate and newspapers began reporting that the prime minister had suffered a mental breakdown and was insane. Pitt responded by passing new laws that enabled the government to suppress and regulate newspapers. Britain's financial problems continued and in his budget of December 1798 William Pitt introduced a new graduated income tax. Beginning with a 120th tax on incomes of £60 and rising by degrees until it reached 10% on incomes of over £200. Pitt believed that this income tax would raise £10 million but in fact in 1799 the yield was just over £6 million. In

1797 Pitt appointed Lord Castlereagh as his Irish chief secretary.

This was a time of great turmoil in Ireland and in the following year Castlereagh played an important role in crushing the Irish uprising.

Castlereagh and Pitt became convinced that the best way of dealing with the religious conflicts in Ireland was to unite the country with the rest of Britain under a single Parliament. The policy was unpopular with the borough proprietors and the members of the Irish Parliament who had spent large sums of money purchasing their seats.

Castlereagh appealed to the Catholic majority and made it clear that after the Act of Union the government would grant them legal equality with the Protestant minority. After the government paid compensation to the borough proprietors and promising pensions, official posts and titles to members of the Irish Parliament, the Act of Union was passed in 1801.

George III disagreed with Pitt and Castlereagh's policy of Catholic Emancipation. When Pitt discovered that the king had approached Henry Addington to become his prime minister, he resigned from office.

Although Pitt had been paid £10,500 a year as prime minister, he was now deeply in debt and for a while he feared that he would be declared bankrupt. A group of friends agreed to help but it was only after selling his family home that he was able to satisfy his creditors. In May 1804 Henry Addington resigned from office and once again William Pitt became prime minister. Lord Castlereagh was appointed Secretary for War but many leading politicians, including Charles Fox, refused to serve under Pitt. Out of the twelve man cabinet, only Pitt and Castlereagh were from the House of Commons.

With Napoleon planning to invade England, Pitt quickly formed a new coalition with Russia, Austria and Sweden. When the French were defeated at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21st October 1805, Pitt was hailed as the savior of Europe. However, Napoleon fought back and in December, 1805 he triumphed over the Russians and Austrians at Austerlitz. Pitt was devastated by the news of Napoleon's victory and soon after was taken seriously ill. William Pitt died on 16th January, 1806. He was so heavily in debt that the House of Commons had to raise £40,000 to pay off his creditors.

Hoppner’s portrait of Pitt the Younger is arguably one of the finest likenesses of one of Britain’s Prime Ministers. Pitt sat for Hoppner at the artist's residence in 1805, during his second brief term as Prime Minister. It would be his last portrait sitting. Hoppner’s work is the most statesman-like of Pitt’s portraits, and has become perhaps the best-known likeness of him. The sculptor Joseph Nollekens used Hoppner’s original when making his own posthumous likeness, in conjunction with a death mask.

Hoppner’s original portrait was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1806, the year of Pitt’s death. The picture was widely admired, and though some criticized the apparent severity of the characterisation, it was considered to be Hoppner’s best work. It accords well with the testament of another portraitist, John Opie, who remarked on “a power of expression that was extraordinary” in Pitt’s eyes. Pitt and Hoppner were close contemporaries and the evident world-weariness in the heavy eyelids and solemnity of expression suggests a certain amount of empathy on the artist's part as his sitter's health began to deteriorate.

After Pitt’s death Hoppner received numerous demands for replicas of his original from Pitt’s friends and colleagues. Most were three-quarter length, as the original, for which Hoppner charged 80 guineas. (This contrasts with Nollekens’ bust, of which there are seventy-four versions, and which cost 120 guineas each.) Inevitably, many of Hoppner’s versions were completed with studio assistance.

Smaller versions such as the present example were reproduced by studio assistants such as R. R. Reinagle, who is believed to have produced thirteen half-lengths, as well as four whole-lengths. Many of Hoppner’s replicas were taken directly from the original canvas, now at Cowdray Park, which was specifically retained by the artist for this purpose.

Porter, Sir Robert Ker [pseud. Reynold Steinkirk] (1777–1842), painter, writer, and diplomat, was born in Durham on 26 April 1777, one of the five children of William Porter (1735–1779), who was buried at St Oswald's, Durham, in 1779 after twenty-three years' service as surgeon to the 6th Inniskilling dragoons. He was descended from an old Irish family, whose ancestors included Sir William Porter, who fought at Agincourt, and the royalist Endymion Porter. His mother was Jane (1745–1831), daughter of Robert Blenkinsop of Durham. She died at Esher, Surrey, aged eighty-six. Robert's brothers, both older than him, were William Ogilvie Porter, a naval surgeon, who after his retirement from the navy practised over forty years in Bristol and died there on 15 August 1850 aged seventy-six, and Colonel John Porter, who died in the Isle of Man, aged thirty-eight, in 1810. His sisters, both novelists, were Jane Porter (bap. 1776, d. 1850) and Anna Maria Porter (1778–1832). Robert spent his boyhood in Edinburgh, where his mother had moved in 1780; she was very poor, and depended largely on the support of her husband's patrons in the army. In Edinburgh, Robert attracted the notice of Flora Macdonald, and, in consequence of his admiration for a battle piece in her possession depicting some action in the fighting of 1745, he determined to become a painter of military subjects. In 1790 his mother took him to Benjamin West, who was so impressed by the vigour and spirit of some of his sketches that he procured his admission as a Royal Academy student at Somerset House. He entered the Royal Academy Schools on 18 February 1791, aged thirteen.

Porter's progress was remarkably rapid. In 1792 he received a silver palette from the Society of Arts for a biblical drawing, The Witch of Endor. In 1793 he was commissioned to paint an altarpiece for Shoreditch church; in 1794 he painted Christ Allaying the Storm for the Roman Catholic chapel at Portsea; and in 1798 St John Preaching for St John's College, Cambridge. In 1799, when he was living in London with his sisters Jane and Anna Maria, at 16 Great Newport Street, Leicester Square (formerly the house of Sir Joshua Reynolds), he became a member of a small club of young artists, known as the Brothers, founded by Louis Francia for the cultivation of Romantic landscape painting. Girtin, who then lived in the immediate neighbourhood, was also a member. The artistic precocity of Bob Porter, as he was known, and the skill with which he wielded the ‘big brush’ were already fully recognized, and in 1800 he obtained congenial work as a scene-painter of Othello's ‘antres vast and desarts idle’ at the Lyceum exhibition room in the Strand, on the site of what was to become the Lyceum Theatre; but in 1800 he astonished the public by his Storming of Seringapatam, an impressive panorama, 120 feet in length, with 700 life-size figures and stated on the good authority of Jane Porter to have been painted in six weeks. This huge picture covering 2550 square feet of canvas was supported on rollers and, extending to three-quarters of a circle, was one of the first of such works which subsequently became extremely popular, especially in France; it was also lucrative, according to account books in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. After its exhibition at the Lyceum it was rolled up, but was later destroyed by fire; yet the original sketches and engravings of it by Giovanni Vendramini preserve some evidence of its merits. Other successful comparable works were The Battle of Lodi (1803), also exhibited at the Lyceum, and the Defeat of the French at Devil's Bridge, Mont St Gothard, by Suwarrow in 1804; to accompany these explanatory handbooks were issued. Other battle pieces, in which Porter displayed qualities of vigour, though bordering sometimes on the crude, and a daring compared by some to that of Salvator Rosa, were Agincourt (executed for the City of London), the Battle of Alexandria, the Siege of Acre, and the Death of Sir Ralph Abercrombie, all of which were painted about the same time. Porter also worked on easel-pictures, and in 1801 he exhibited at the Royal Academy a successful portrait of Mr and Mrs Harry Johnston as Hamlet and Ophelia. In all, between 1792 and 1832 he exhibited thirty-eight pictures, the majority being either historical pieces or landscapes. In 1797 he founded, with the aid of his sisters and with some support from Thomas Frognall Dibdin, a periodical called The Quiz; it had a very brief existence. His own contributions appeared under the pseudonym Reynold Steinkirk.

In 1803 Porter was appointed captain of the Westminster militia, but his family's urgent solicitations deterred him from becoming a regular soldier, a career which attracted him more strongly than any other. In 1805, however, his restless and energetic nature was encouraged by an invitation from Tsar Alexander I of Russia to paint some vast historical murals for the admiralty in St Petersburg, and he immediately started for the Russian capital. While in St Petersburg he won the affections of a Russian princess, Mary, daughter of Prince Theodor de Scherbatoff. The courtship was postponed after the tsar had signed the treaty of Tilsit with Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, thus aligning Russia with the enemy of Great Britain. In view of this, and mindful of his own safety, Porter crossed into Finland on 10 December 1807, and from there he entered Sweden where, for reasons unknown, he had in 1806 been knighted by the eccentric King Gustavus IV. He then visited several of the German courts, was in 1807 created a knight of St Joachim of Württemberg, and subsequently accompanied Sir John Moore (whom he had met and captivated while in Sweden) to Spain. He was with Moore's expedition throughout, was at Corunna, and was present at the death of the general. He returned home with many sketches of the campaign. In the mean time, in 1809, there appeared his Travelling Sketches in Russia and Sweden during the Years 1805–1808, in two sumptuous quarto volumes, elaborately illustrated by Porter himself; yet this work showed neither outstanding literary ability nor any special gift of observation. It was followed after a brief interval by Letters from Portugal and Spain, Written during the March of the Troops under Sir John Moore (1809).

In 1811 on the tsar's invitation, Porter returned to Russia, where on 7 February 1812 he at last was able to marry his Russian princess. He was subsequently accepted in Russian military and diplomatic circles and became well acquainted with the Russian version of the events of 1812–13, of which he gave a graphic account in his Narrative of the Campaign in Russia during 1812; it was printed seven times. He had returned to England before his book appeared, and was on 2 April 1813 knighted by the prince regent, two months before the birth of his daughter Mary (Mashinka) on 8 June. He was soon back in Russia, and in August 1817 he started from St Petersburg on an extended course of travel, proceeding through the Caucasus to Tehran, thence southwards by Esfahan to the site of ancient Persepolis, where he made many valuable drawings and transcribed a number of cuneiform inscriptions. After a sojourn at Shiraz he retraced his steps to Esfahan, and proceeded to Ecbatana and Baghdad; and then, following the course of Xenophon's Katabasis, to Scutari. He published the records of his long journey in his Travels in Georgia, Persia, Armenia, Ancient Babylonia, 1817–1820 (2 vols., 1821). This huge book, which is full of interest and a great advance upon his previous books of travel, was illustrated by bold drawings of mountain scenery, of works of art, and of antiquities. A large number of Porter's original sketches are preserved in the British Museum, to which they were presented by his sister, Jane. At Tehran, Porter had an audience with the Persian monarch Futteh Ali Shah, whose portrait he drew, and from whose hands, in 1819, he received the insignia of the order of the Lion and of the Sun. After a brief return to England he left again for Russia, but was in 1825 appointed British consul in Venezuela. During the fifteen years in which he held that position, he resided at Caracas, where he kept up an extensive hospitality, and became well known and generally popular. He continued to draw, and painted several large sacred subjects, including Christ Instituting the Eucharist, Christ Healing a Little Child, Ecce homo, and St John Writing the Apocalypse. He also painted a portrait of Simón Bolívar, hero of South American independence and founder of the republic of Colombia. In 1836 he advised the Venezuelan congressional commission on the design of the republic's coat of arms.

During his years as consul Porter did much to reconcile strong local Catholic intolerance towards non-Catholic foreigners living in the country. For example, before his time, protestants had to bury their dead in their own gardens or plantations, as they were barred from Catholic cemeteries. Porter, with some financial support from the British government, and to some extent at his own cost, succeeded in establishing a protestant burial-ground in Caracas. In recognition of the many benefits he had obtained for the protestant community in Venezuela, he was created in 1832 a knight commander of the order of Hanover. He returned to England in 1841. His wife had died at St Petersburg, of typhus, on 27 September 1826, but their only daughter was still living in the Russian capital, having in 1837 become the wife of Pierre de Kikine, a captain in the imperial guard. After a short stay with his brother, Dr William Ogilvie Porter, at Bristol, he left in company with his sister Jane on a visit to Mme Kikine. On 3 May 1842 he wrote from St Petersburg to tell his brother that he was on the eve of sailing for England; but he died suddenly of apoplexy on the following day as he was alighting from his coach, after returning from a farewell visit to Tsar Nicholas I. He was buried in St Petersburg. A marble tablet was placed in the cloisters of Bristol Cathedral commemorating several members of the Porter family, Sir Robert among them.

Owing to his large expenditure, Porter's affairs were left in some disorder, but his estate was finally wound up in August 1844 by his executor, Jane Porter, who spoke of him with great affection as her ‘beloved and protecting brother’. His books, engravings, and antiquities were sold at Christies on 30 March 1843. His drawings included twenty-six illustrations to the odes of Anacreon (engraved by Vendramini, and published in 1805 by John P. Thompson), a large panoramic view of Caracas, and a very interesting sketchbook (forty-two drawings) of Sir John Moore's campaigns, which was presented by his sister to the British Museum.

A man of the most varied attainments, Porter has been justly described as ‘a distinguished British gentleman and diplomat, and artist’ (Porter, cviii), but is probably now best remembered as an artist. He was a splendid horseman, excelled in field sports, and possessed the gift of finding acceptance by people of every rank.

Thomas Seccombe, rev. Raymond Lister DNB