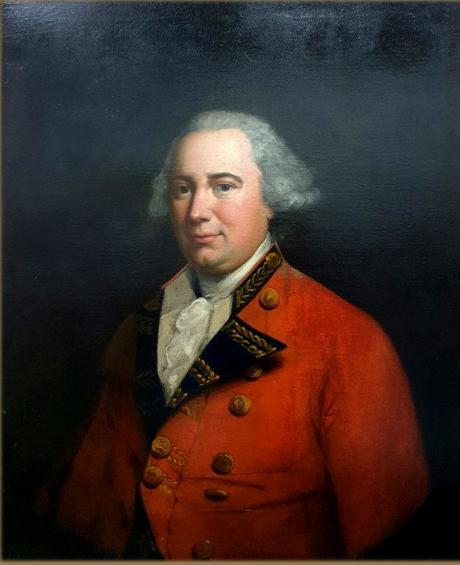

inscribed on two lables " General Henry P****le " and " Major General Pringle".

The Pringles of Caledon are believed to descend from the Pringles of Torsonce. The John Pringle of Lyme Park who migrated to Ireland with Hamilton is believed to be the youngest (4th) son of James (2) Hoppringill of that Ilk. This John Pringle was born circa 1642 and was at one time the factor of the Earl of Lauderdale. If so, he would be the youngest brother of George Hoppringill of that Ilk and uncle to John, the last Hoppringill of that Ilk who died in 1737.

Spouse: Mary Godley

Marriage: 02 May 1767 in St. Mary's, Dublin [2]

Children:

William Henry Pringle

Caroline Pringle

Elizabeth Pringle

Henry was the second son of John Pringle of Lyme Park, Co. Tyrone. In 1747 he became Ensign in Otway's Regt. on Irish half pay, in 1750 Lieut,. in Blackeney's Regt. (Enniskilllngs), in 1756 Major in the 56th Regt., ("Caledonian Mercury" 25 Sep 1765, page 2: Yesterday, Henry Pringle, Esq; kissed his Majesty's hand at St. James's, on being appointed Major to the fifty-sixth regiment of foot.)

In 1758 ("Washington County, New York: Its History to the Close of the Nineteenth Century" by William Stone, 1901, page 92: Chapter IX. 1758-1763. The campaign against Canada, of 1758, opened with great apparent spirit; the hostile incursions of the Canadian Indians serving to rouse the Colonists to greater activity. On the 13th of March of that year, a party of some seven hundred French and Indians, commanded by Duvantaye and the Sieur de Langly, surprised and fell upon a detachment of two hundred rangers, under Major Rogers, who were scouting in the neighborhood of Ticonderoga. The Indians brought back one hundred and forty-four scalps and some prisoners, among the later of whom were two officers --- Captain, afterwards Major-General Henry Pringle, and Lieutenant Roche. Rogers retired with fifteen men and two officers. Three days afterwards, these two officers, having wandered around and lost themselves in the forest in a vain attempt to escape, came into Fort St. Grederick (Ticonderoga) and surrendered themselves to the French.

The Battle on Snowshoes . . . Lieutenant Henry Pringle, writing later as a French prisoner, described the conclusion of the action to his former commanding officer: Capt. Rogers with his party came to me, and said (as did all those with him) that a large body of Indians had ascended to our right; he likewise added, what was true, that the combat was very unequal, that I must retire, and he would give Mr. Roche and me a Sergeant to conduct us thru the mountain. No doubt prudence required us to accept his offer; but, besides one of my snowshoes being untied, I knew myself unable to march as fast as was required to avoid becoming a sacrifice to an enemy we could no longer oppose. I therefore begged of him to proceed and then leaned against a rock in the path, determined to submit to a fate I thought unavoidable. Unfortunately for Mr. Roche, his snow-shoes were loosened likewise, which obliged him to determine with me, not to labour in a flight we both were unequal to.

In the event Pringle and Roche both managed to escape from the battlefield in the darkness. They wandered in the forest half frozen until 20 March 1758, seven days later, when they reached Fort Carillon and succeeded in surrendering to French officers before the Indians encamped around the fort could claim them as captives. )

In 1767 Henry married a daughter of the Rev. Dr Godley, Ireland (G. M.). He had issue, a daughter Caroline, who in 1797 marr. Robert, son of the late Sir Richard St George, Bart.; also a son William-Henry (G. M.).

In 1779 Lieut.-Col. in the 51st Foot, ("Saunder's News-Letter" 5 Mar 1779, page 1:

War-office, Feb. 27, 1779. His majesty has been pleased to appoint the following . . .

Lieutenant-Colonels to be Colonels: . . . Henry Pringle, of 51st foot. )

in November 1782 Major-General (S. M.). In January 1782 General Murray, while defending Port St Philip in the Island of Minorca, which was besieged by the French, declared to his officers that he would never surrender until driven to the last extremity, and they, including Colonel Henry Pringle, replied that they would obey his orders. In February Governor Murray writes as to the unhappy differences between the Lieut.-Governor and himself relative to the surrender of the Island to the French. Later, a complaint having been presented against Murray, it was found that the case could not be tried for want of Colonel Pringle who was left hostage for the transport vessels.

"Edinburgh Magazine" Vol. 14, 1799 [sic], page 240:

Deaths. 1800.

Feb. 9. At Caledon, in Ireland, Major-Gen. Pringle, who served his King and Country many years as an officer of the first eminence.

John Singleton Copley, (1738–1815), portrait and history painter, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on 3 July 1738 at Long Wharf, the first and only child of Mary Singleton (c.1710–1789) and Richard Copley, shopkeepers who emigrated from Ireland some time in the mid-1730s. Richard Copley died some time in the mid-1740s, but his widow and son continued the family business of cutting and selling tobacco until 1748.

America, 1738–1774

Copley's formal education during his childhood remains a mystery. But his home on Long Wharf, the centre of Boston's thriving merchant economy, which accounted for 40 per cent of the total volume of colonial American shipping, was a de facto classroom that taught Copley market lessons that he would later apply to his artistic career.

In 1748 Copley's widowed mother married Peter Pelham (1695–1751), an émigré English artist and schoolteacher who had arrived in America in 1727. Pelham had been married twice before and had four sons and a daughter of his own. Ten-year-old Copley and his mother moved into Pelham's house on Lindel's Row, which was in a district of artisans near the centre of Boston. A half-brother, Henry Pelham (1749–1806), born the next year, would become a miniaturist, printmaker, and map maker of some reputation.

Copley's artistic education must have begun at about this time. He learned to mezzotint, a print technique that generates form in tonal areas rather than in lines, from his stepfather, who had achieved prominence in London and Boston for his work in that medium. Copley's first artistic effort, a mezzotint of the Revd William Welsteed, was printed in 1753 from the rescraped plate his stepfather had used to produce his own portrait of the Revd William Cooper ten years earlier. Peter Pelham also opened his library of English prints to his stepson and probably arranged to have Copley visit the studio of John Smibert (1688–1751), the leading artist of Boston during Copley's childhood. The ambitious late baroque pictures (241 painted in Boston) of this Scottish émigré, who arrived in Boston in 1729 after pursuing a moderately distinguished career in London, had established a new standard of excellence for many American colonial artists. Smibert's studio also offered Copley a look at English and European prints, theoretical treatises on art, and plaster casts from the antique. As a result, Copley's first paintings, of 1754, were mythological works: The Forge of Vulcan (priv. coll.), Galatea (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and The Return of Neptune (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), all based on European prints and more consistent with baroque English taste than the traditional American taste for portraits.

Pelham also passed entrepreneurial skills on to his stepson. Like most household producers in Boston, Pelham, and later Copley, had to be marketing tacticians capable of identifying, satisfying, and at times creating the desire to own works of fine art. Copley in particular was at the forefront of the process of Anglicization, in which the newly wealthy merchant élite of Boston began to covet and consume luxury English goods, or facsimiles of them, including portraits in the formal English style. Even in his early twenties, the marketwise Copley competed with the English rococo artist Joseph Blackburn, then resident in Boston, for commissions. He imitated Blackburn's technique so successfully that the English artist was forced to return home in 1763, leaving the 25-year-old Copley in control of the burgeoning market for paintings in Boston.

Without the benefit of an art academy or further instruction from Pelham, who died in 1751, Copley taught himself, often by imitating the English prints that could be bought or viewed in Boston. He studied prints after paintings by Sir Godfrey Kneller, Thomas Hudson, and Sir Joshua Reynolds. For example, his Mrs Daniel Hubbard (1764; Art Institute of Chicago), is explicitly based on John Faber's print after a Hudson portrait of Mary Finch, Viscountess Andover (c.1746). The prints were of twofold importance in Copley's self-improvement: first for teaching him contemporary compositional patterns, and second for providing knowledge of current English imagery that allowed his upmarket Anglophile clients to be persuasively portrayed as sophisticated English ladies and gentlemen.

In the late 1750s and early 1760s, Copley developed his signature style, which was descriptive and marked by meticulous detail, crisp lines and edges, strong colour, and dramatic tonal contrasts. His portraits of Mary and Elizabeth Royall (c.1758; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Moses Gill (1764; Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island), and Nathaniel Sparhawk (1764; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) are exemplary. He was so fastidious in his technique that Gilbert Stuart once commented on a realistic passage in Copley's Epes Sargent (1760; National Gallery of Art, Washington): 'Prick that hand and blood will spurt out' (S. Benjamin, Art in America, 1880, 20). Copley's sitters often mentioned the numerous sittings he required, one recalling the twenty visits needed for Mr and Mrs Thomas Mifflin (1773; Philadelphia Museum of Art). Though he often based his compositions on English prints, he could not learn English brush technique from them, and as a result his paintings veered away from the fluid effects of the artists of London, such as Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, who preferred painterly brushwork and atmospheric veiling. In that way he was like other artists, such as Joseph Wright of Derby and Tilly Kettle, who were working in provincial areas of Britain.

In an effort to improve his art and to acquire an English metropolitan manner in his early career, he shipped his portrait of his half-brother Henry Pelham, Boy with a Squirrel (1765; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), to London for exhibition at the Society of Artists the following year. Reynolds said it was 'a very wonderfull Performance', but noted 'a little Hardness in the Drawing, Coldness in the Shades, An over minuteness' (Jones, 41–2). Benjamin West also praised Copley's painting, but thought it 'too liney, which was judged to have arose from there being so much neetness in the lines' (ibid., 44). Reynolds and West agreed that Copley must leave America to study in Europe and London before, as the former phrased it, 'your Manner and Taste were corrupted or fixed by working in your little way at Boston'.

The exhibition, however, did result in Copley's election as a member of the Society of Artists in London. In 1767 Copley sent to London a second picture, Young Lady with a Bird and Dog (Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio), but to English academic eyes he again missed the mark. Citing first the overall detailing and the opacity and brightness of colour, West added that 'Each Part being … Equell in Strength of Coulering and finishing, Each Making too much a Picture of its silf, without that Due Subordanation to the Principle parts, viz they head and hands' (Jones, 56–7). He repeated the admonition to come 'home' to London 'before it may be too late for much Improvement' (ibid., 60).

Though Copley wrote back to lament a situation in America in which he had to paint pictures in a place where 'the people regard it no more than any other usefull trade … like that of a Carpenter, tailor or shew maker, not as one of the most noble Arts in the World' (Jones, 65–6), he was, none the less, extremely popular in the late 1760s, producing some of colonial America's most memorable images. Among them are the merchants John Hancock (1765; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Nicholas Boylston (1767; Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts), and Jeremiah Lee (1769; Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford, Connecticut); the ladies Mrs Samuel Quincy (c.1761; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Mrs Thomas Boylston (1766; Harvard University), and Rebecca Boylston (1767; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston); the ministers Myles Cooper (1768; Columbia University, New York) and Nathaniel Appleton (1761; Harvard University); and the artisans Paul Revere (1768; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and Nathaniel Hurd (c.1765; Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio).

In the 1760s Copley also pioneered miniature and pastel painting in America, in both of which he was self-trained. His experimental oil on copper miniatures of the late 1750s were superseded about 1762 by a more delicate watercolour on ivory technique (for example, Jeremiah Lee, c.1769; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Copley drew about fifty-five pastels in America, beginning in 1758 (for example, his Self-Portrait, 1769; Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware).

By 1771 Copley had become so renowned in New England and along the Atlantic seaboard that he was invited to New York city, where he spent six months and reached the pinnacle of his American fame with portraits so powerful and austere that they bear more resemblance to the French neo-classical art of Jacques-Louis David than to contemporary English painting. His portraits of Mrs Thomas Gage (1771; Putnam Foundation, Timken Museum, San Diego) and Samuel Adams (c.1770–72; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), painted in Boston, are among the most arresting pictures painted in colonial America.

In 1769 Copley married Susannah Farnham Clarke (1745–1836), the daughter of Richard Clarke, the official agent of the British East India Company in Boston, and purchased a 20 acre farm on Beacon Hill, next to the estate of John Hancock. Political events, especially the Stamp Act of 1765, the Townshend Acts of 1767, the non-importation movements that they provoked, and the Boston massacre of 1770, led to the destabilization and polarization of Boston society. Copley had friends and clients in both tory and whig factions. On the one hand he counted radical whigs such as Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Paul Revere as his friends, actually painting Adams as a political firebrand. On the other hand, he had married into a prominent tory family and painted many tories, including Thomas Gage, the British commander in North America and the colonial governor of Massachusetts from 1774 to 1775. Copley, however, never labelled himself politically and rarely expressed a clear political position. But he did have a political opinion, namely that he felt threatened, both personally and professionally, by the growing crisis, and wished the clock could be turned back a decade or two to when America was under the invisible benefaction of English rule. He claimed to dissociate himself from partisan politics in the higher name of art, and began, as early as 1766, to imagine himself emigrating, breaking the ‘shackels’ of relentless portrait painting, and abandoning the comforts of his annual income of 300 guineas.

The defining event in Copley's decision to emigrate was the Boston Tea Party of 1773. Because his father-in-law had been importing tea under an exclusive contract with the East India Company, a situation that was emblematic of British control of American markets, he was under ferocious whig attacks led by Samuel Adams. Copley attempted to forestall political action against the Clarkes, but after Adams exhorted 8000 Bostonians at South Church in November of that year, a group of activists disguised as Mohawks boarded Richard Clarke's tea ship and dumped all 342 casks in the harbour. That and other pre-Revolutionary events traumatized the Copley and Clarke families. Copley himself was threatened by marauding whigs; the retaliatory Coercive Acts and Boston Port Bill ruined the economy; British warships began filling the harbour; and Copley knew he had to leave the city, which he did on 10 June 1774, lamenting the inevitable 'Civil War', as he called it. In May of 1775, war having broken out, his wife, three children, and the Clarkes left for England. His mother, Mary, half-brother, Henry Pelham, and sickly infant son, Clarke, remained in Boston.

Britain, 1774–1815

After a 21-year career in America, Copley moved on to a fourteen-month tour of the continent, largely in Italy, and then to a highly successful second career of some forty years as a portrait and history painter in London. Though John Adams had lauded him as 'the greatest Master that ever was in America' (L. H. Butterfield, ed., Adams Family Correspondence, 1963, 2.103), he was known in London only as the author of two exhibition pictures and as a correspondent with Benjamin West; on the continent he was unknown entirely. In order to adapt to and succeed in his new cultural environment he embarked on a study of antiquity and the old masters, long beyond the age at which English artists had done so. Travelling with the English artist George Carter, he set off late in 1774 for Rome via Rouen, Paris, Lyons, Marseilles, Toulon, Antibes, Genoa, Pisa, and Florence. He studied the work of Raphael in particular, unapologetically basing his first European painting, The Ascension (1775; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) on the Italian's late Transfiguration. Late in 1775 he travelled via Parma, Venice, the Tyrol, Mannheim, and Cologne to London, where he joined his wife and three eldest children: Elizabeth (b. 1770); John Singleton Copley, later Baron Lyndhurst (b. 1772); and Mary (b. 1773). His son Clarke died in Boston, and a third daughter, Susanna, was born.

In 1776, at the age of thirty-eight, Copley settled into a house on Leicester Fields, was elected associate of the Royal Academy, and submitted his portrait Mr and Mrs Ralph Izard (1775; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) to the Royal Academy's annual exhibition. Ever ambitious, he submitted four more pictures to the Royal Academy in 1777, including the large Copley Family (1776–7; National Gallery of Art, Washington) which was attacked in the London press. His English portrait style was a modification of his American style, keeping many of the poses, the sharp light and dark contrasts, and bright colouring he was accustomed to, but now loosening the brushwork somewhat, reducing the details, attempting more group portraits, and concerning himself more with the representation of social rank. Exemplary works are Sir William Pepperell and his Family (1778; North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh), Clark Gayton, Admiral of the White (1779; NMM), Henry Laurens (1782; National Portrait Gallery, Washington), William Murray, First Earl of Mansfield (1783; NPG), The Three Youngest Daughters of George III (1785; Royal Collection), Richard, Earl Howe, Admiral of the Fleet (c.1791–1794; NMM), Baron Graham (c.1804; National Gallery of Art, Washington). During this period Copley was elected a Royal Academician (1779); saw the birth (1782) and death (1785) of his third son, Jonathan; and the death of his daughter Susanna (1785). He moved to George Street near Hanover Square, London (1783), visited Ghent, Flanders, Brussels, and Antwerp (1787), and lost the election for the presidency of the Royal Academy to Benjamin West (1792). It was remarkable that Copley, whose artistic education had taken place thousands of miles from London, would vie for the president's chair of the Royal Academy. But it was equally understandable that he would lose, for he thought of himself, more so than his peers at the Royal Academy, as an autonomous professional with a style of his own. Decades of self-reliant work in Boston, without the company of professional colleagues, had set him on that path, as had his innately independent thinking.

Copley's primary artistic goal in London was to paint historical subjects, which Reynolds and others considered the highest branch of painting. He painted seven religious subjects. Prominent among them were The Tribute Money (1782; RA), which was his belated diploma picture for the Royal Academy; Samuel Relating to Eli the Judgements of God on Eli's House (1780; Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut); and Saul Reproved by Samuel for not Obeying the Commandments of God (1798; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). He once painted a subject from literature, The Red Cross Knight (1793; National Gallery of Art, Washington), from Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queen.

Copley's primary focus, however, was on contemporary history painting, on which he intended to build his artistic reputation. His first, and most spectacular and novel, was Watson and the Shark (1778; National Gallery of Art, Washington), which the London press favourably reviewed. Unlike most contemporary history paintings that depicted heroic subjects of national magnitude, for example, Benjamin West's The Death of General James Wolfe (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; replica, Royal Collection), Copley's picture was commissioned by Brooke Watson, a merchant and, later, lord mayor of London, and is concerned with a macabre and wholly personal episode in Watson's young adulthood. In 1749 the fourteen-year-old Watson, who was then a crewman on a British ship, went for a swim in Havana harbour, where he was attacked by a shark that mutilated his right leg below the knee. Copley's picture depicts the climactic moment of the shark wildly pursuing its already injured prey moments before a group of fellow crewmen drive it away and pull Watson from the waters. Despite the idiosyncratic and biographical nature of the subject, Copley based passages of the picture on old master paintings, according to the theoretical dictates for history painting advocated by Reynolds and practised by West. For example, the man in the prow who is about to jab the shark with a boat hook suggests traditional pictures of St Michael casting out Satan; the crewmen reaching out of the boat towards Watson are based on figures in Raphael's Miraculous Draught of Fish; and the wild-eyed figure of Watson flailing in the water is adapted from another in Raphael's Transfiguration.

As a tale of physical trial and emotional trauma, followed by salvation, the subject of Watson and the Shark was more in the literary tradition of Daniel Defoe's The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1719) than it was in the pictorial tradition of English history painting. The theme of triumph over adversity must have been on Watson's mind when he commissioned the picture, however, for he bequeathed it to Christ's Hospital, London, with the hope that it would 'hold out a most usefull Lesson to Youth' (will of Brooke Watson, 1807, TNA: PRO).

Copley's next historical subject, the Death of the Earl of Chatham (1779–81; Tate collection), incorporated portraits of fifty-five of England's noblemen. It shows William Pitt, first earl of Chatham, collapsing in the House of Lords on 7 April 1778 during his reply to the duke of Richmond's speech in favour of American independence. Not only did Copley break with tradition by combining history painting with portraiture, he also marketed his picture in a novel way, by renting a private venue for its exhibition, which was in direct competition with the Royal Academy's annual exhibition of 1781. He charged for admission and earned more money from prints made after the painting and marketed for him by the print publisher John Boydell.

Boydell commissioned and eventually paid Copley £800 for The Death of Major Peirson (1782–4; Tate collection), which was again exhibited privately and for profit at 28 Haymarket. Boydell also arranged for the accompanying print sale. A highly dramatic picture, painted at the peak of Copley's powers, it depicts the events of 6 January 1781 when Peirson valiantly died leading his troops during the French invasion of the island of Jersey. Copley carefully researched the details of the town's appearance and correctly recorded the uniforms, but in accord with Reynolds's theory of history painting he also idealized Peirson's death, turning him into a modern Patroclus. The picture's composition was based on the tripartite structure of Benjamin West's The Death of General James Wolfe (1771) but now made more densely populated and physically animated.

The Peirson attracted the interest of George III, who reportedly devoted three hours to study of its 'various excellencies, in point of design, character, composition, and colouring' (Morning Herald and Daily Advertiser, 22 May 1784). The picture, with its brilliant reds and whites, theatrical lighting, and sophisticated composition, all put to the service of glorifying English heroics, captured the patriotic imagination of viewers who eagerly looked to military events, such as the defence of Jersey in 1781 and the defence of Gibraltar in 1782, that would ease their sense of the impending loss of America. The corporation of London rewarded Copley for the Peirson with a commission for a huge picture, The Siege of Gibraltar (1783–91; Guildhall Art Gallery, London), for a final sum of £1100. The picture glorifies British magnanimity in the midst of battle as officers risk their lives in the aftermath of victory to rescue the enemy from their exploding ships. General George Augustus Eliott (later Lord Heathfield) is depicted large on a white horse, directing the rescue.

To display the picture, which took eight years to paint, Copley had to erect a tent in Green Park, London. He said that 60,000 came to see it, paying the 1s. admission price (Anecdotes of artists of the last fifty years, Library of the Fine Arts, 4, July 1832, 25). Four years later Copley exhibited at Spring Gardens Charles I Demanding in the House of Commons the Five Impeached Members (Boston Public Library). Earlier in subject than his previous history paintings, the exhibition of the picture was not well attended. In 1799 Copley attempted a last private showing of a historical picture, The Victory of Lord Duncan (1798–9; Dundee Art Galleries and Museums), which depicts the surrender at the battle of Camperdown of the Dutch Admiral DeWinter to Admiral Duncan on 11 October 1797.

After 1800 the quality of Copley's work was in decline. One version of The Offer of the Crown to Lady Jane Grey (1807–8; Somerset Club, Boston) was well received at the Royal Academy. But his George IV (1804–10; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), an equestrian portrait, was poorly composed and highly criticized. In the early nineteenth century he became preoccupied with petty squabbles with clients and fellow artists. He went into debt. Commissions became scarce. His half-brother Henry Pelham drowned in Boston in 1806. Finally, his health deteriorated and he became feeble in both mind and body. His Battle of the Pyrenees (1812–15; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and The Siege of Dunkirk (1814–15; College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia) were inept. When the young American artist Samuel F. B. Morse visited Copley in 1811, he wrote:

He is very old and infirm … His powers of mind have almost entirely left him; his late paintings are miserable; it is really a lamentable thing that a man should outlive his faculties. He has been a first-rate painter, as you well know. I saw at his room some exquisite pieces which he painted twenty or thirty years ago, but his paintings of the last four or five years are very bad. He was pleasant, however, and agreeable in his manners.

E. L. Morse, ed., Samuel F. B. Morse: his Letters and Journals, 1914, 1.47

Copley suffered a stroke at dinner on 11 August 1815. He was left paralysed and incapable of speaking. He died at his home in George Street, London on 9 September 1815, and was buried in Croydon, Surrey. After his death, the family was supported by John Singleton Copley junior, a lawyer, who was elected to parliament in 1818, made Baron Lyndhurst in 1827, and was the first lord chancellor to have been born outside Britain.

Copley was the greatest and most influential painter in colonial America, producing about 350 works of art. With his startling likenesses of persons and things, he came to define a realist art tradition in America. His visual legacy extended throughout the nineteenth century in the American taste for the work of artists as diverse as Fitz Hugh Lane and William Michael Harnett. In Britain, while he continued to paint portraits for the élite, his great achievement was the development of contemporary history painting, which was a combination of reportage, idealism, and theatre. He was also one of the pioneers of the private exhibition, orchestrating shows and marketing prints of his own work to mass audiences that might otherwise attend exhibitions only at the Royal Academy, or who previously had not gone to exhibitions at all.