Lord Randolph Henry Spencer Churchill, (1849–1895), politician, was born at 3 Wilton Terrace, Belgravia, London, on 12 February 1849 (b. cert.; Winston Churchill's biography gives 13 February 1849), the third son of John Winston Spencer Churchill, seventh duke of Marlborough (1822–1883), and his wife, Lady Frances Anne Emily (1822–1899), daughter of Charles William Vane, third marquess of Londonderry, and his wife Frances Anne Vane.

Education and marriage

Churchill was sent to Mr Tabor's preparatory school at Cheam, where he displayed an interest in history and a character which, according to a contemporary, was 'sometimes impetuous, sometimes imperious, always irrepressible' (Gordon and Gordon, 1.24). At Eton College (1863–5) his record was unremarkable, but he became friends with Arthur Balfour and Lord Rosebery, who were to have an important influence on his political career. At Oxford (1867–70) he read jurisprudence and modern history at Merton College, where he was well regarded by his history tutor, Mandell Creighton. In 1883 Churchill told Creighton that 'The historical studies which I too lightly carried on under your guidance have been of immense value to me in calculating and carrying out actions which to many appear erratic' (DNB). His accurate knowledge of Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was noted by the history examiners, who included E. A. Freeman. Churchill spent much of his time at Oxford hunting or steeplechasing, and he was one of the founders of the Merton dining club the Myrmidons. He obtained a second-class degree in 1870, and then spent much of the next three years at Blenheim, where he hunted with a pack of harriers.

In 1873 Churchill met, at a ball at Cowes, a young American, Jeanette (Jennie) Jerome (1854–1921), the daughter of Clara and Leonard Jerome, a wealthy New York financier. Mrs Jerome and her daughters had come to England from Paris, after the fall of the Second Empire, and they were quickly received into society. Randolph and Jennie fell in love and became secretly engaged, but it took them six months to persuade their parents to allow them to marry. At this time, it was virtually unprecedented for the son of a leading aristocrat to marry an American, but Churchill was only the younger son of a poor duke, and when Leonard Jerome agreed to settle £50,000 on the couple, the duke agreed to the marriage. Randolph and Jennie [see Churchill, Jeanette] were married at the British embassy in Paris on 15 April 1874, and their first child, Winston Churchill (the future prime minister), was born prematurely at Blenheim Palace on 30 November 1874. Their younger child, John (Jack), was born in February 1880.

Conservative back-bencher

Churchill shared the Conservative politics of his parents, and in 1868 he had published a letter defending his father's conduct in connection with the parliamentary election at Woodstock. In 1874, in return for his father's consent to marry, Churchill agreed to stand at the general election as the Conservative candidate for the borough of Woodstock, where his father was the principal landowner. In his election address he called for a more economical defence policy—a portent of his future policy. He defeated his Liberal opponent, George Brodrick (a fellow of Merton College) by a majority of 165 votes out of a total electorate of 1147. His maiden speech in the House of Commons, on 22 May 1874, prompted compliments from Harcourt and Disraeli, who wrote to the queen: 'the House was surprised, and then captivated, by his energy and natural flow and his impressive manner' (Monypenny & Buckle, 2.652). The hallmark of Churchill's early parliamentary career was his loyalty to his family—which did not always equate with loyalty to the Conservative leadership. In 1878 he publicly attacked the County Government Bill of the Disraeli government and privately criticized its Eastern policy as too warlike and too anti-Russian—another pointer to his later views.

In the early 1870s Churchill became a friend of the prince of Wales, who was already friendly with his elder brother, the marquess of Blandford. The prince, who liked Americans, favoured Churchill's marriage to Jennie, and his private secretary, Francis Knollys, was the best man at their wedding. In 1875 Churchill criticized the tory government's financial provision for the prince's visit to India in a letter which Disraeli dismissed as an ill-informed Marlborough House manifesto which had destroyed Churchill's 'rather rising reputation' (Monypenny & Buckle, 2.769–70). While the prince was in India his companion, the earl of Aylesford, decided to divorce his wife and cite the marquess of Blandford as co-respondent. To prevent a scandal, Churchill threatened to make public intimate letters which the prince of Wales had written to Lady Aylesford some years before. Aylesford abandoned his divorce proceedings, but the prince was outraged by Churchill's conduct and demanded a formal apology, which Churchill eventually sent from the USA, where he and Jennie had gone to escape the fracas.

The Aylesford affair made the Churchills personae non gratae in London society, so the duke of Marlborough accepted Disraeli's offer to become lord lieutenant of Ireland—a post he had turned down twice before. Churchill became his father's unofficial private secretary, and in January 1877 he and his family took up residence in Dublin, next to the vice-regal lodge, in Phoenix Park. By working and travelling with his father, he learned about Irish conditions and mixed with members of the Dublin Castle administration, including the government's law adviser, Gerald Fitzgibbon, who became a lifelong friend. He also got to know a few nationalists, such as the leader of the Home Rule Party, Isaac Butt—who preferred the tories to the Liberals. Thus Churchill gained valuable experience about the country which was to dominate parliamentary politics during the rest of his career.

Churchill was a strong supporter of the legislative union with Ireland—a stance which he inherited from both his parents. His mother was a daughter of the third marquess of Londonderry, the half-brother of Viscount Castlereagh, who had engineered the 1801 Act of Union. His father, as lord lieutenant of Ireland, was the recipient of Beaconsfield's 1880 general election address, which drew attention to the home-rule threat. Churchill, in his own 1880 election address, opposed the repeal of the Union, but also favoured reform of the Irish land tenure laws in the interests of internal peace. The electoral defeat of the Conservatives ended his stay in Dublin, but he made good use of his knowledge of Irish politics when he returned to England. He denounced the compensation for disturbance clause in the Relief of Distress Bill as 'an attempt to raise the masses against the propertied classes' (Hansard 3, 253, 1880, col. 1640) and opposed unlimited coercion, arguing that force was not a long-term remedy. He sought to build an alliance between the tories and the Irish Roman Catholic hierarchy on denominational education and hostility to secular radicalism. His speech on Ireland at Preston, in December 1880, was the first of his speeches to be reported verbatim in a metropolitan newspaper.

The ‘Fourth Party’

The victory of the Liberal Party at the 1880 general election had convinced Churchill that the electorate favoured Gladstone's policies of peace, retrenchment, and reform. Thus he sought to undermine Gladstone's ministry by claiming that it was untrue to its own principles. Churchill had previously been an inactive back-bencher, but in 1880 and especially in 1881 he intervened constantly in debates. He became the leader of a small group of tory MPs below the gangway—John Gorst, Henry Wolff, and Arthur Balfour—whose independent attacks on the government from below the gangway earned them the nickname the Fourth Party. The group first came together to oppose the admission of Charles Bradlaugh, the atheist Liberal, to the House of Commons. In this matter Churchill was motivated not just by partisan opportunism but also by religious belief and parental example. His opposition to Gladstone's 1883 Affirmation Bill recalled his father's opposition to the alteration of the parliamentary oath in 1857. Churchill's denunciation of Bradlaugh's republicanism helped him to restore his credit with the prince of Wales, and he tried to exploit the hostility of the Catholic Irish MPs to Bradlaugh's advocacy of birth control. The opposition of Churchill and the Fourth Party to Bradlaugh did not prevent his eventual admission to parliament, but it did lead to the creation in 1883 of the Primrose League, which was dedicated to the defence of religion and the monarchy. Churchill was the first member of the league and his mother and wife became prominent members of the ladies' branch. The league quickly became a major force in popular Conservatism and the largest voluntary political organization in late Victorian Britain.

Churchill's activities as the leader of the Fourth Party were initially welcomed by the Conservative leader in the Commons, Sir Stafford Northcote, who was a friend of his father. But their relations deteriorated early in 1883 when Northcote attempted to make him toe the official party line. Churchill replied that:

Members who sit below the gangway have always acted in the House of Commons with a very considerable degree of independence of the recognized and constituted chiefs of either party; nor can I (who owe nothing to anyone and depend upon no one) in any way or at any time depart from that well-established and highly respectable tradition.

Churchill to Northcote, 9 March 1883, BL, Iddesleigh MSS

Churchill also publicly criticized the dual leadership of the party—by Northcote in the Commons and Salisbury in the Lords—which he blamed for the tory surrender on the Irish Arrears Bill in 1882 (The Times, 2, 9, April 1883). He questioned Northcote's leadership qualities and claimed that Salisbury was the only man capable of defeating and replacing Gladstone. In an anonymous article entitled 'Elijah's mantle' (Fortnightly Review, May 1883), he further argued that the leader of the tory party should be a member of the House of Lords, where he could influence government policy even when the party was in opposition. But Churchill's initiative merely prompted tory MPs to show their overwhelming support for Northcote.

Tory democracy

Since Churchill's views on the leadership were not supported by the tory parliamentary party, he switched his campaign to the party in the country. In 1882 he had been elected a member of the council of the National Union of Conservative Associations, and at its 1883 conference he attacked the Conservative Party's central committee, which was chaired by Edward Stanhope, a supporter of Northcote. He contrasted the closed character of the central committee with the representative nature of the national union, but his attack on the central committee was not endorsed by Salisbury. Churchill did not wish to create an American-style caucus which would determine party policy, but his support for the national union gained him a reputation as a champion of ‘tory democracy’. In reality, Churchill was a late and cautious convert to the cause of democratic toryism: in 1878 he had complained that Sclater-Booth's County Government Bill was based 'like the rest of recent Tory legislation, upon principles which were purely democratic' (Hansard 3, 238, 1878, col. 907). In 1882 Churchill declined Gorst's suggestion that he should place himself at the head of a democratic tory party, and dissociated himself from the phrase ‘tory democracy’ when it was used at the Liverpool by-election. In 1884 he opposed the second reading of the Liberals' Reform Bill, but he then decided to support the measure when it became clear that change was inevitable. In 1885 Churchill defined ‘tory democracy’ as merely popular support for the monarchy, the House of Lords, and the Church of England—the traditional bulwarks of toryism.

Churchill showed little interest in social questions and he did not advocate expensive welfare measures. In 1883 he stressed that public-health reforms should be thrifty and opposed the principle of a graduated water tax. In 1884 he introduced a Leasehold Enfranchisement Bill, which was inspired partly by his own experiences as a tenant in London and partly by a desire for revenge on those whig peers who had supported Irish land legislation. Unlike Salisbury, Churchill took no interest in working-class housing, although it was a fashionable issue at the time. His popularity with the masses owed little to his direct interest in their welfare, but much to the nature of his platform speeches. Working men liked Churchill to 'give it 'em hot', and his pungent oratory prompted one of his regular listeners to remark that 'the tomahawk was always in his hand' (Curzon, 37). Some of the more notorious examples of his oratory may be apocryphal since they cannot be found in contemporary sources, but Churchill certainly flavoured his speeches with many colourful analogies drawn from Dickens, history, and sport. At Birmingham he described Chamberlain as 'a pinchbeck Robespierre' (The Times, 15 Oct 1884), and at Paddington he compared the conflict between Britain and Russia to the great fight between Heenan and Sayers (ibid., 7 May 1885). Churchill also drew on his intimate knowledge of the King James Bible, which provided him with a host of dramatic and forceful stories. He compared Gladstone with Herod and Gamaliel, and once asked, after the death of General Gordon at Khartoum, 'how many more of England's heroes … are to be sacrificed to the Moloch of Midlothian?' (ibid., 18 Feb 1885). Churchill emphasized Gladstone's apostasy from his Midlothian principles when he delivered a triad of speeches at Edinburgh in December 1883. But his most famous attack on Gladstone was at Blackpool, when he described the prime minister as 'the greatest living master of the art of personal advertisement' (ibid., 25 Jan 1884). His comments prompted Gladstone to observe that vulgar abuse always emanated from the scions of the highest aristocracy. His taunts usually succeeded in getting a response from Gladstone, which only helped to boost Churchill's reputation.

Churchill always carefully prepared his speeches and wrote them out in full before committing them to memory. He became an outstanding platform orator, but he complained that 'addressing these large meetings is such anxious and exciting work that for a day or two afterwards I am quite useless and demoralized … and the constant necessity of trying to say something new makes me a drivelling idiot' (Churchill to Dufferin, 27 Oct 1885, BL OIOC, Dufferin and Ava MSS). The dramatic impact of his speeches was enhanced by his casual stance, dapper appearance, and hand gesticulations, though they reached a mass audience through the columns of the press. He did not mind what the metropolitan papers said about him as long as they reported his speeches verbatim. The Times was often critical of the personal nature of Churchill's political attacks, but Algernon Borthwick's two Conservative papers, the daily Morning Post and the weekly St Stephen's Review, consistently supported him. Churchill attached much political importance to the provincial press, and in 1885 he helped to create a Conservative News Agency to provide copy for provincial papers. He believed 'that a party makes its own press, but a press will never make a party' (Speeches, 1.205). Churchill's distinctive physiognomy, especially his moustache, was a gift to illustrators and cartoonists. Although he was not a short man, Tenniel depicted him as a pygmy knight-errant and Phil May drew him as a baby—both implying that he had ambitions above his standing. Churchill was not offended by such caricatures, and he kept by his desk a framed copy of Tenniel's cartoon of him as a circus clown.

By 1884 Churchill had established a strong position for himself within the Conservative Party. In December 1883 he was elected—by a narrow majority—chairman of the council of the national union and continued his war against the central committee, but was not supported by Salisbury. Consequently Churchill resigned the chairmanship in May 1884, which prompted a provincial movement in his favour and his unanimous re-election as chairman. In July, Salisbury—without consulting Northcote—jointly agreed with Churchill to abolish the party's central committee, and thus acknowledged his influence within the party. The Reform Bill of 1884 heralded a redistribution of parliamentary seats which would disenfranchise the borough of Woodstock and oblige Churchill to find a new constituency. Thus, early in 1884 he boldly agreed to stand as a tory candidate for the Central division of Birmingham—the most Liberal city in England. In his speeches in Birmingham, Churchill skilfully wooed the electors with a mixture of traditional toryism, imperialism, and Gladstonian Liberalism. He claimed that the Liberal government had abandoned its commitment to peace and retrenchment. Churchill's campaign for financial retrenchment was a key element in his political strategy. In 1883 he had called for a £10 million reduction in spending to be achieved by cuts in the army and the civil service. At Blackpool in 1884 he declared that national thrift was essential in the context of the current economic recession.

Secretary of state for India

When the reform crisis was over Churchill, who badly needed a rest, spent three months during the winter of 1884–5 touring India. His visit was a pioneering one, for very few other front-bench politicians had visited the country. Churchill stayed with senior government officials and closely studied the character of the raj. On his return to Britain, he described British rule in India as 'a sheet of oil spread out over a … profound ocean of humanity' (Speeches, 1.212). He warned parliament that the raj would last only as long as Britain showed itself capable of ruling, but would collapse 'the moment we showed the faintest indications of relaxing our grasp' (Hansard 3, 292, 1885, col. 1540). When a Russian incursion into Afghanistan—the Panjdeh incident—aroused alarm about the security of India, Churchill wanted Britain both to support the amir of Afghanistan and to reach an accommodation with Russia. His views on the crisis largely accorded with those of Salisbury, who rewarded him when he came to power.

In May 1885 Churchill helped to orchestrate the defeat of Gladstone's Liberal government on a budget amendment opposing the increase in taxation and the absence of rate relief. The government resigned a few days later, and the composition of the new minority tory ministry reflected Churchill's growing influence over the party. Salisbury became prime minister; Hicks Beach was chancellor of the exchequer and leader of the Commons, while Northcote—ennobled as the earl of Iddesleigh—held the largely nominal post of first lord of the Treasury. Churchill became secretary of state for India—a post he occupied for seven months and which he greatly enjoyed.

At the India Office, Churchill worked well with the permanent under-secretary, Sir Arthur Godley, the India council, and the viceroy, Lord Dufferin. He attacked the previous viceroy, Lord Ripon, for neglecting India's security and he persuaded parliament to vote a special credit for the defence of India. He welcomed Salisbury's Afghan frontier agreement with Russia and, partly for electoral reasons, endorsed Dufferin's annexation of Upper Burma, which was the last significant expansion of British India. Churchill left the India Office in February 1886, after Gladstone's return to power, but India remained prominent in his thoughts thereafter.

Ireland: unionism and the Orange card

Churchill's Irish policy during Salisbury's minority ministry of 1885–6 has been the subject of much controversy. His opposition to the renewal of the Coercion Act and his support for an inquiry into the Maamtrasna murders gave rise to the suspicion that he would support home rule in order to retain nationalist support for Salisbury's minority government. Churchill, however, had never regarded coercion as a long-term solution and he had previously supported a re-examination of the Maamtrasna verdicts, which he considered unsound. He favoured a measure of popular local government for Ireland, but he remained publicly committed to the Union and disapproved of Carnarvon's secret talks with Parnell about home rule.

At the general election in December 1885 Churchill contested the Central division of Birmingham against John Bright and lost by 773 votes—a creditable performance. His calls for ‘fair trade’ and an imperial commercial union proved popular with the artisans, and Chamberlain later acknowledged Churchill's influence on his tariff reform policy. Churchill had not expected to win his contest at Birmingham, so he had also agreed to stand for South Paddington, which was one of the safest Conservative seats in London. There he was elected by a comfortable majority, and he represented the constituency for the rest of his life.

After the narrow victory of the Liberals at the 1885 general election—which left them in need of support from the Irish nationalists—Gladstone espoused the policy of home rule. Churchill immediately appreciated the significance of this development and his response was unequivocal: he advised Salisbury to defend the Union by forming an alliance with Hartington and the other Liberals who opposed home rule. Churchill was the first prominent politician to advocate the creation of a ‘unionist party’—a coalition of Conservatives and unionist Liberals—which would maintain Britain's ties not only with Ireland but also with India and the empire.

Churchill also decided to ‘play the Orange card’—to exploit the strong opposition of Ulster protestants to home rule. In a speech at Belfast, in February 1886, he referred to his own Ulster ancestry and predicted that the enactment of home rule would occasion unconstitutional action. He did not, however, endorse Orange militancy and he appealed to loyal Catholics to support the Union. Salisbury observed that Churchill had 'said nothing to which any catholic could object' (Salisbury to Churchill, 24 Feb 1886, Randolph Spencer Churchill MSS). In a published letter Churchill also advocated enlightened unionism, but stated that if the Liberal government ignored the opposition to home rule, then 'Ulster will fight, Ulster will be right' (The Times, 8 May 1886).

When the Home Rule Bill came before the House of Commons, Churchill adopted a moderate stance. He warned unionist Liberals not to be mesmerized by 'the wand of the magician' (Hansard 3, 304, 1886, col. 1343) and skilfully undermined Gladstone's attempt to minimize Liberal dissension on the second reading of the bill. After the defeat of the measure, Gladstone appealed to the country and Churchill threw his parliamentary caution to the winds. His election address was an impassioned attack on Gladstone and his home-rule policy. He claimed that both the British constitution and the Liberal Party were being broken up merely 'to gratify the ambition of an old man in a hurry' (Churchill, Lord Randolph Churchill, 860). His attack on Gladstone's personal power was typically colourful, but it was also reminiscent of Gladstone's own denunciation of ‘Beaconsfieldism’.

Leader of the house and chancellor of the exchequer

After the Unionist victory at the general election, Salisbury formed a Conservative government and offered Churchill the leadership of the House of Commons on the recommendation of Hicks Beach. Churchill accepted the post on the understanding that Beach became chief secretary for Ireland—the most difficult post in the government. As leader of the house, Churchill was hampered by the lack of a Conservative majority and the frequent absences of the Liberal Unionists, but he dealt ably with the short parliamentary session of August and September 1886. He proposed to curb Irish obstruction by enabling parliamentary debates to be closed by simple majority voting—a policy which was adopted in 1887. Churchill combined the leadership of the house with the post of chancellor of the exchequer and was thus second only to Salisbury in the ministerial hierarchy.

In the autumn of 1886 Churchill almost seemed to supplant Salisbury as the effective leader of the Conservative Party. In a speech at Dartford, in October, he warned Conservatives not to rest on their laurels since 'Politics is not a science of the past; politics is a science of the future'. He also declared that 'The main principle and guiding motive of the Government in the future will be to maintain intact and unimpaired the union of the Unionist party' (The Times, 4 Oct 1886). He believed that this objective could best be ensured by adopting progressive policies which would appeal to Liberal Unionists and to the county electors who had deserted the tories in 1885. Thus he advocated a number of rural reforms: popular county government, allotment provision, land law revision, and relief from tithes and rates. The ‘Dartford programme’ prompted the St Stephen's Review (9 October 1886) to describe Churchill as 'The central figure in English politics' and the Pall Mall Gazette to claim that Churchill was the real leader of the party. In Punch, Tenniel depicted Churchill as 'The political Jack Sheppard'—stealing the radical programme from under the nose of Gladstone. These allegations were unjustified, however, for Churchill's Dartford programme echoed Salisbury's Newport programme of 1885 and had been approved by his cabinet colleagues.

Despite Churchill's ability to capture the political limelight, he privately admitted that he had little direct influence over Salisbury's government. His only protégé in the cabinet was the home secretary, Henry Matthews—the first Roman Catholic to become a secretary of state and the first Conservative to represent Birmingham for over a century. Churchill's support for Matthews reflected his non-sectarian brand of unionism and his continued interest in Birmingham politics. Churchill's hopes for an extensive reform programme aroused little enthusiasm in the cabinet. He wrote despairingly to Salisbury: 'I am afraid it is an idle schoolboy's dream to suppose that Tories can legislate … legislation is not their province in a democratic constitution … I believe Gladstone to be the fated governor of this country' (Churchill to Salisbury, 8 Nov 1886, priv. coll., Salisbury MSS).

As chancellor of the exchequer Churchill was determined to be a retrencher and a reformer in the mould of Gladstone. He opposed the continuation of the metropolitan coal and wines dues on the grounds that they were both a restriction on free trade and a burden on the London poor. His draft budget for 1887 proposed a radical overhaul of the tax system which was a precedent for twentieth-century reforms. He proposed to take 3d. off income tax, lower the duty on tea and tobacco, graduate the house and death duties, and double the government's rate support grant to local authorities. The scheme, though radical, was relatively kind to landowners and not socially redistributive.

Resignation

Churchill and Salisbury shared a largely similar political ideology, but Salisbury lost patience with Churchill on a personal and tactical level. Salisbury acknowledged Churchill's ability, but complained that he had a 'wayward and headstrong disposition' and likened the cabinet to 'an orchestra in which the first fiddle plays one tune and everybody else, including myself, wishes to play another' (Salisbury to Cranbrook, 26 Nov 1886, Gathorne-Hardy, 2.265). Churchill was an awkward colleague, but as the party leader in the Commons he was subject to many pressures which were not faced by Salisbury or that half of the cabinet who sat in the Lords. When Alfred Austin, editor of The Standard, falsely alleged that Churchill wished to supplant the premier, Salisbury observed that 'the qualities for which he is most conspicuous have not usually kept men for any length of time at the head of affairs' (Salisbury to Austin, 30 Nov 1886, Autobiography of Alfred Austin, 2.248).

Randolph's resignation from Salisbury's cabinet in December 1886 was the most controversial episode in his controversial career. His action has been widely regarded as evidence of his egotistical and unjustified belief in his own indispensability. Yet resignation, or the threat of resignation, was a tactic commonly employed by Victorian ministers. Both Gladstone and Salisbury, for example, had resigned from the cabinet when they were about the same age as Churchill was in 1886. There was also a more immediate precedent for Churchill's resignation. In February 1886 Harcourt, the Liberal chancellor of the exchequer, had submitted his resignation when the cabinet refused to cut the defence estimates, but Gladstone had persuaded him to remain by agreeing to reduce the estimates. Ten months later Churchill tried the same strategy, but failed to win over Salisbury.

Churchill's priority as chancellor was financial retrenchment, and he wanted, for electoral reasons, to reduce the defence estimates below those of the last Liberal government. This was opposed by the secretary for war, W. H. Smith, who was coping with the consequences of Harcourt's reduction earlier in the year. The dispute came to focus on the £500,000 allocated for the fortification of ports and coaling stations, although this was of only incidental concern to Churchill. When Smith refused to give way, Churchill wrote to Salisbury, on 20 December 1886, stating his wish to resign from the government since he could not accept the defence estimates and did not expect support from the cabinet. Salisbury, in reply, supported the demands of his service ministers and accepted Churchill's resignation with 'profound regret' (Salisbury to Churchill, 22 Dec 1886, Randolph Spencer Churchill MSS). Churchill then justified his resignation by linking his desire for economy with wider issues:

I remember the vulnerable and scattered character of the empire, the universality of our commerce, the peaceful tendencies of our democratic electorate, and the hard times, the pressure of competition, and the high taxation now imposed … it is only the sacrifice of a chancellor of the exchequer upon the altar of thrift and economy which can rouse the people to take stock of their lives, their position and their future.

Churchill to Salisbury, 22 Dec 1886, ibid.

Churchill feared that the growth of the defence estimates would encourage Britain to become unnecessarily embroiled in continental struggles. He opposed Iddesleigh's Russophobic foreign policy and wanted to give Russia a free hand in the Balkans in return for non-interference on the Indian frontier. But the abdication of Prince Alexander of Bulgaria threatened to embroil Britain in a new Balkan confrontation with Russia, which Churchill feared would imperil the tory government, reunite the Liberal Party, and thus assist the cause of home rule. At Dartford he described the Bulgarian crisis as 'far more serious than any other matter' (The Times, 4 Oct 1886), and his fear of a European war increased his determination to reduce the estimates. While his resignation failed to do this, it did lead Salisbury to remove Iddesleigh from the Foreign Office, and the premier did not support the queen's attempt to restore Alexander—a Battenberg relative—to power in Bulgaria.

Churchill's resignation also reflected his determination to maintain the union with Ireland 'not for a session, or for a Parliament, but for our time' (R. Churchill to Akers-Douglas, 1 Jan 1887, Churchill, Lord Randolph Churchill, 640). He was fairly happy with the government's Irish policy, but he feared that its English policy would enable Gladstone soon to return to power and implement home rule. Churchill hoped that his resignation would help to turn the tory party into a more powerful governing force. In his resignation statement, he stressed the need to reduce wasteful public expenditure and called for a select committee to examine the defence estimates. The committee was established and Churchill, as its first chairman, conducted a full inquiry. He advocated a thorough reform of naval and military administration at Wolverhampton in June 1887, and wrote a perceptive memorandum on the subject which was published in the report of the Hartington commission on the army in 1890.

Churchill's resignation was also encouraged by the poor state of his health, which made the strains of office hard to bear and probably exacerbated his disagreements with colleagues. He was gloomy about his own prospects and reportedly predicted 'six months office for me and then Westminster Abbey' (Edward Hamilton, diary, BL, 3 Sept 1886). After leaving office, he admitted that he was physically exhausted and immediately went on a long vacation to the Mediterranean to recuperate. Churchill had been subject to serious bouts of illness since 1882 and he was probably suffering from secondary syphilis. His illness certainly reduced his stamina, but its effect on his judgement and intellect is more problematical. He continued to write speeches and letters which were masterpieces of exposition and argument until shortly before his death.

Post-resignation politics

Churchill's resignation did not, in itself, rule out a return to office at some stage in the future. Salisbury expressed the hope that the Conservative Party would have the advantage of his services in the future, and W. H. Smith, who succeeded him as leader of the House of Commons, assured him that his resignation was merely 'An incident in the career of a young politician of quite a temporary character' (Smith to Churchill, 13 Jan 1887, W. H. Smith archives, W. H. Smith MSS). Churchill's resignation actually strengthened his appeal to some progressive tory MPs who still regarded him as a potential leader of the party. They included Louis Jennings (who edited his speeches and was his principal lieutenant until 1890), Ernest Beckett, and Henniker Heaton. Churchill himself continued to show a strong interest in politics, and his personal papers contain as much material on the period after his resignation as for the period before it.

Salisbury believed that Churchill's resignation had been prompted by his friendship with Chamberlain, and Harcourt compared Churchill and Chamberlain to married women who had lost their reputations and had to find new friends. Churchill's resignation convinced Chamberlain that the reactionary tories were in the ascendant, and encouraged him to explore the possibility of Liberal reunion at the Round Table talks with the Gladstonians in January 1887. Those talks prompted Churchill to declare that although the Liberal Unionists had been 'a useful kind of crutch' he looked solely to the tory party for the preservation of the Union (Hansard 3, 310, 1887, col. 289). After the failure of the Round Table talks, Churchill and Chamberlain briefly considered creating a progressive ‘national party’, but they soon disagreed over Balfour's Irish Land Bill—the former favouring the landlords and the latter the tenants. Churchill also disliked Chamberlain's plan for home rule on the Canadian model, and he regarded the whigs—'Hartington and all he represents' (Churchill to the dowager duchess of Marlborough, 17 Aug 1887, Randolph Spencer Churchill MSS)—as the essential ingredient in Liberal Unionism.

Churchill's relations with Chamberlain were also strained by their apparent rivalry in Birmingham, where the local tories wanted Churchill to stand again at the next election. Churchill, however, did not want to disrupt the Unionist alliance in the city, and when John Bright died in March 1889 Churchill declined an invitation from the Birmingham Conservatives to stand for the vacant constituency. Chamberlain appealed to Salisbury and Balfour to persuade the Birmingham tories to support a Liberal Unionist candidate—Jacob Bright—and then claimed all the credit for his election. Churchill accused Chamberlain of ingratitude, but declined to compete with him for the favour of the Cecils. The episode reflected Churchill's willingness to subordinate his own personal advantage to the Unionist cause.

Later years and death

In the late 1880s and early 1890s Churchill took an active interest in horse-racing. He was elected a member of the Jockey Club and leased Banstead Manor, near Newmarket, as his country home. In partnership with Lord Dunraven he bred racehorses with considerable success—winning the Oaks in 1889 with a horse which he had personally selected. For a time he seemed more interested in racing than politics, but the two pursuits were interlinked at the time—as Hartington and Rosebery also demonstrated. Churchill still retained a strong interest in many political issues, including foreign affairs. In the winter of 1887–8 he made an unofficial, but well-publicized, visit to Russia, where he had a private meeting with Tsar Alexander III at which he advocated an Anglo-Russian understanding as beneficial to both parties. Churchill wanted closer ties with Russia and France both because he wanted to protect the British empire and because he sought to keep the United Kingdom out of Germany's orbit. He mistrusted Bismarck, but when he met the retired statesman at Kissingen in 1893 he was much impressed by his character and demeanour. Churchill's views on foreign policy were too independent for Salisbury, who in 1891 turned down his request for the vacant post of British ambassador to France.

For a long while after his resignation Churchill broadly supported the Salisbury government's Irish policy. When Balfour became chief secretary for Ireland in 1887 Churchill welcomed his tough policy against the National League, but in 1888 he privately observed that 'Balfourism acts like a blister on Ireland' (Churchill to Lord Justice Fitzgibbon, 15 Feb 1888, W. Churchill, Lord Randolph Churchill, 714) and warned that too protracted an application of coercion would do more harm than good. Churchill wanted to conciliate the Irish by giving them the same representative county government that was being given to England and Wales. He believed that equality of treatment for all the countries in the Union was the only way of defeating home rule. In 1890 Churchill privately criticized the government's decision to establish a special parliamentary commission to investigate the allegations of The Times concerning 'Parnellism and crime'. When the commission issued its report Churchill, in the House of Commons, attacked the constitution of the commission and its refusal to condemn The Times for libelling Parnell. His speech was criticized by some Conservatives, but his repeated references to the forger, Pigott, were less offensive to the House of Commons and to the press than has been claimed. The Morning Post continued to support Churchill and soon afterwards published his lengthy criticisms of Balfour's Land Purchase Bill.

Churchill believed that the union with Ireland would be preserved only if the tories adopted progressive reforms in Britain. Thus, in a speech at Walsall in July 1889 he called for a number of social reforms, including an eight-hour day for coalminers and licensing reform. In 1890 he introduced his own licensing bill, which proposed a modified version of popular control of the liquor trade and attracted some cross-party support, but it was not supported by the government. Churchill was also interested in the labour question and supported the principle of labour representation in parliament. He believed that ‘new unionism’ was more favourable to the tories than the older form of trade unionism. He drew attention, before the 1892 general election, to the growing political power of organized labour and predicted that in the future 'Labour laws will be made by the Labour interest for the advantage of Labour' (Churchill to Arnold White, 29 April 1892, Randolph Spencer Churchill MSS). He called on Conservatives and Unionists to promote the interests of labour in order to ensure working-class electoral support for the union of the United Kingdom.

When Balfour succeeded Smith as leader of the Commons in 1891, Churchill concluded that tory democracy was dead, and he thought of quitting politics altogether. His health was deteriorating and he increasingly displayed symptoms of petulance and irritability. In order to recuperate his health and restore his depleted finances, Churchill spent most of 1891 on an extended visit to South Africa. There he shot wild game, made judicious investments in the goldmines, and concluded that he had been wrong to oppose Gladstone's South African policy in 1881. He recorded his impressions in a series of letters to the Daily Graphic, later published as Men, Mines and Animals in South Africa (1892). At the general election of 1892 he was re-elected, without a contest, for South Paddington and, following the return of Gladstone and the Liberals to power, sat on the opposition front bench. In 1893 he ably attacked both the Irish Home Rule Bill and the Welsh Disestablishment Bill. In 1893 he accepted an invitation to stand for the Central division of Bradford, but his candidature again ruffled Chamberlain's feathers. Nevertheless Chamberlain spoke on Churchill's behalf at Bradford and praised his services to the Unionists. In 1894 the onset of general paralysis impeded Churchill's ability to speak, and he made his last speech in the Commons in June of that year. He was persuaded to embark on a round-the-world trip accompanied by his wife and doctor. They visited the United States, Canada, Japan, and finally India, where the rapid deterioration in Churchill's health forced an immediate return to England. He died at his mother's home, 50 Grosvenor Square, London, on 24 January 1895, and was buried four days later in the churchyard at Bladon, near Blenheim. It was widely believed that his final illness was tertiary syphilis, though it has been suggested latterly that he could have suffered from multiple sclerosis or a brain tumour (Foster, 218; Sunday Telegraph, 6 Oct 1996).

Reputation and assessment

Rosebery considered Churchill's career one of the most interesting of the nineteenth century: 'His career was not a complete success and yet it was far from a failure' (Primrose, 110). This was a fair verdict on an exceptional politician who possessed many strengths and some obvious weaknesses. The Pall Mall Gazette (22 June 1886) described Churchill as 'the Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde of modern politics' and Gladstone observed that Churchill would make an excellent public servant if the bad half of his character was removed. Churchill was often rude, egotistical, or impatient, and even his friend Rosebery thought that he had something of the spoilt child about him. Yet Churchill also had charm, charisma, and courage—he admitted fearing only two men: Bismarck and Gladstone. Although Churchill liked wine, women, gambling, and horse-racing, he was not a vulgar aristocratic philistine. He was well read (in both English and French) and his speeches displayed an original and wide-ranging intellect. When his collected speeches were published in 1889, John Morley praised their literary form and political foresight, and Mandell Creighton considered them 'a substantial contribution to political thought in England' (Creighton to Churchill, 11 April 1889, Randolph Spencer Churchill MSS). Churchill was a serious politician whose ability impressed most of those who came into close contact with him. Iddesleigh, who had no reason to compliment Churchill, regarded him as the shrewdest member of the 1885 cabinet.

Churchill's political career was far more consistent than many of his contemporaries and his most recent biographer have alleged. Churchill's own assessment of his speeches was substantially correct: 'I think it will be difficult for any one who reads the speeches to maintain any substantial charge of inconsistency against me. The only sharp curve I executed was on the Reform question and that is susceptible of explanation' (Churchill to his mother, 12 Aug 1887, Randolph Spencer Churchill MSS). Churchill consistently supported the union with Ireland and progressive reforms which would make the union more popular with both the Irish and the British people. He played a major role in ensuring that the Unionist coalition—which he named and helped to create—dominated British politics for most of the late Victorian period. Nevertheless Churchill was modest about his own contribution to British politics and at no stage did he seek to supplant Salisbury as the leader of the tory party or the country.

Churchill's support for legislative and party reform in the mid-1880s gave him a reputation as a tory democrat which greatly influenced his subsequent career and his posthumous reputation. Nevertheless there was little that was distinctly democratic about Churchill's toryism, which was a mixture of traditional support for the crown, the Lords, and the church, together with a commitment to the peace, reform, and retrenchment policies of Gladstone and Peel. Churchill's enormous and growing respect for Gladstone was evident in their private relations and latterly in his public speeches. His respect for Peel was equally great, and in a speech at Bow he told the tories that they 'would have to do again the work of Sir Robert Peel' (The Times, 4 June 1885). He later described Peel as the greatest tory minister of the century and the progenitor of tory democracy. Thus in ideological terms, Churchill belonged to the bipartisan mainstream of Victorian parliamentary politics.

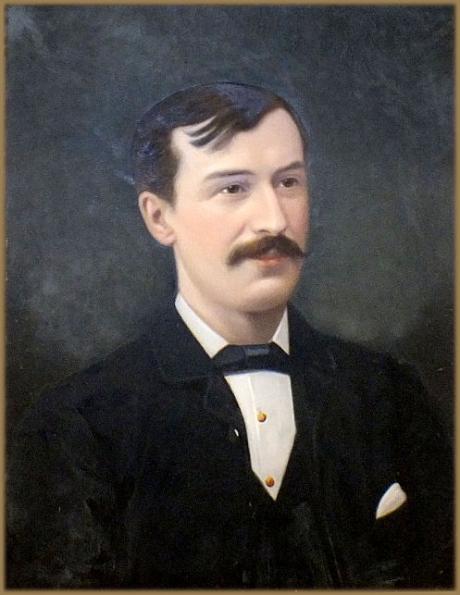

Two oil paintings of Churchill were commissioned during his lifetime. Edwin Long painted him for the Constitutional Club, and Edward Ward's portrait of Churchill as chancellor of the exchequer was acquired by Winston Churchill and now hangs at Chartwell. There is also a marble bust of Churchill in the members' corridor of the House of Commons. Churchill's most important memorial, however, was the political career of his eldest son, Winston.

Churchill, after the custom of his class and age, spent little time with either of his sons, but he was much concerned with Winston's welfare and often wrote to him. When Winston later reread his father's letters, he realized how much he had thought and cared for him. Winston greatly admired his father, 'learnt by heart large portions of his speeches', and took his politics 'almost unquestioningly from him' (Churchill, Thoughts and Adventures, ). Winston's desire to become his father's political lieutenant was dashed by his death, but Winston was determined to vindicate his memory. In 1906 he published a two-volume biography of his father, which remains the most detailed written up to the end of the twentieth century. Winston believed that he owed everything to his father, and this feeling did not wane with the passage of time. Winston, moreover, followed his father's aims and endorsed most of his policies, such as ‘tory democracy’, Liberal–Conservative coalition, army reform, and financial retrenchment. He also shared his father's belief that Britain should be friends with France, Russia, and the United States. Thus Randolph Churchill's policies and ideology permeated the outlook of the leading British statesman of the twentieth century.