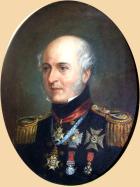

Sir JOHN HARVEY, army officer and colonial administrator; b. 23 April 1778 in England; m. 16 June 1806 Lady Elizabeth Lake, and they had five sons and one daughter; d. 22 March 1852 in Halifax.

Unlike most of his contemporaries in the higher ranks of the British army and the colonial service, John Harvey was not born to the purple; he described himself as the child of an obscure Church of England clergyman of modest means who had persuaded William Pitt the younger to give his son a commission in the army. On 10 Sept. 1794 Harvey became an ensign in the 80th Foot. He was fortunate. The regiment had been raised by Henry William Paget, the future Marquess of Anglesey, a distinguished cavalry officer whose family was part of a widespread and influential military network to which Harvey was to owe much of his future advancement. Yet because he lacked the private resources that would have enabled him to rise through the ranks by purchase, Harvey’s progress was slow and was achieved primarily by hard work, talent, and that quality most prized in the 18th-century British army – personal courage in the face of danger. From 1794 to 1796 Harvey saw active service in the Netherlands and along the coast of France, in 1796 at the Cape of Good Hope, from 1797 to 1800 in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and in 1801 in Egypt. From 1803 to 1807 he served in India during the campaigns against the Marathas where by an unusual act of daring he brought himself to the attention of the commander-in-chief, Lord Lake, and was invited to join his staff. While in India he married Lake’s daughter, making another connection that would prove useful in later years. Lady Elizabeth also proved to be the perfect consort for a colonial governor. She was a gracious hostess and actively involved herself in charitable activities. Harvey was affectionately described by one of his friends as a “Soldier of Fortune,” and to the extent that his life was to be spent in a perennial search for a high station in an aristocratic society the description is an apt one. Since he lacked private means, Harvey had to live with financial insecurity, but thanks to his wife his domestic life was relatively stable and untroubled.

Harvey returned to England in September 1807. On 15 July 1795 he had become a lieutenant and on 9 Sept. 1803 a captain; on 28 Jan. 1808 he was promoted major. From January to June 1808 he was employed in England as an assistant quartermaster general and in July 1808 he joined the 6th Royal Garrison Battalion in Ireland under the command of the Earl of Dalhousie [Ramsay*]. On 25 June 1812 he was raised to the rank of lieutenant-colonel and appointed to Upper Canada as deputy adjutant general to John Vincent*. In his haste to reach his new post he travelled overland on snowshoes across New Brunswick in the depth of winter and arrived in Upper Canada early in 1813.

For the duration of the War of 1812 Harvey played a conspicuous part in the campaigns along the Niagara peninsula. His greatest triumph was at the battle of Stoney Creek, one of the most decisive encounters of the war. In May 1813 a large American force of more than 6,000 men landed at Fort Niagara (near Youngstown, N.Y.) and drove the British from Fort George (Niagara-on-the-Lake), Upper Canada. Vincent, with 1,600 infantry, retreated to Burlington Heights (Hamilton), pursued by about 3,500 Americans who camped at Stoney Creek on 5 June. Vincent’s position was precarious since his opponents could expect reinforcements and he could not. As senior staff officer, Harvey was responsible for reconnaissance and he suggested a surprise attack at night to disperse the Americans before they could be reinforced. At 2:00 a.m. he led out about 700 men. Fortunately, the night was dark, the American pickets were bayoneted before they could give the alarm, and the enemy encampment was poorly organized. Although the battle rapidly degenerated into confused fighting in the dark, Harvey was able to withdraw his men in an orderly fashion before dawn. Among their prisoners were the two American generals, and the enemy force, lacking an experienced commander, retreated. Harvey owed much to luck, but he had taken a calculated risk and he had succeeded. If he had failed, the whole of the Niagara district might have fallen to the Americans; his success greatly raised the morale of the British forces throughout Upper Canada. It also established him as an officer of unusual “zeal intelligence & gallantry.” His reputation was enhanced in November 1813 at the battle of Crysler’s Farm, where he earned a medal, and at Oswego, Lundy’s Lane, and Fort Erie in 1814. Despite numerous acts of bravery and the loss of several horses shot from under him, Harvey was wounded only once, at the siege of Fort Erie on 6 Aug. 1814.

As deputy adjutant general, Harvey also had onerous administrative responsibilities. He negotiated terms for paroles and prisoners of war with his American counterpart, Colonel (later General) Winfield Scott, and the two men formed a continuing friendship. Harvey acted as a liaison with Britain’s Indian allies, was responsible for collecting intelligence, and assisted in organizing the provincial militia. Bravery was not an unusual quality among British officers of the period but administrative competence was less common. Harvey’s talents were recognized and he was clearly marked out for future advancement. Unfortunately for him, in December 1814 the war came to an end and a few months later so did the war in Europe. Harvey was now simply one of hundreds of young officers who faced an uncertain future in a period of retrenchment. Promotion was slow because it was by seniority. Although Harvey became a colonel in May 1825, he would not reach the rank of major-general until January 1837 and lieutenant-general until November 1846. Since he had little “Parliamentary Interest” and most of the patronage within the army was distributed by the Duke of Wellington to those who had served under him in Spain or at the battle of Waterloo, Harvey’s chances of employment were slim. Moreover, though awarded a kch and knighted at Windsor, England, in 1824, he was not given the kcb, to which he felt entitled, because his rank in the army was too low. It is not surprising that in 1829 he proclaimed to Dalhousie that “no Credit was to be gained in Canada.”

With the conclusion of hostilities in Canada, Harvey had moved to Quebec City, where he continued to act as deputy adjutant general. In 1817 he was placed on half pay and in 1824 he returned to England. His timing, once again, was fortunate. The Colonial Office had decided to appoint a five-man commission to evaluate the price at which crown land should be sold to the recently formed Canada Company [see John Galt*] and Harvey was selected as one of the two government appointees. The members sailed for Upper Canada late in December 1825 and remained until June 1826 when they returned to present a report which immediately became the focus of a bitter controversy. It recommended the sale of waste lands to the company at a price critics claimed was too low. The Colonial Office ordered a second investigation which concluded that the first commissioners had performed their work hastily and inadequately. Ironically, Harvey had been the only commissioner to advocate a higher price, but for the sake of unanimity he had signed the report. Despite his efforts to dissociate himself from it, he was censured along with his fellow commissioners and his prospects for employment in the colonial service receded.

Finally, in 1828, owing to the influence of Anglesey, Harvey was appointed inspector general of police for the province of Leinster (Republic of Ireland). He assumed his post at a critical moment. Ireland had remained unusually calm during the struggle for Catholic emancipation in the 1820s, but between 1830 and 1838 it was caught up in disturbances over the collection of tithes by the Church of Ireland. The centre of agitation was Leinster and, although Harvey did everything in his power to promote compromise and prevent violence, one of the bloodiest incidents of the period took place within his district: on 14 Dec. 1831, 13 policemen were killed and 14 wounded during a riot. Yet Harvey’s own reputation emerged unscathed. He was popular both with Dublin Castle and with Irish Roman Catholics and in 1832 he was called as a witness before the House of Commons select committee on tithes in Ireland, where he recommended the solution to the problem that was adopted six years later. None the less, he continued to seek employment in the colonies and in April 1836 he was appointed lieutenant governor of Prince Edward Island.

Harvey found himself confronted on Prince Edward Island by problems not dissimilar to those he had faced in Ireland. All of the British North American colonies entered a period of turmoil in the 1830s, but the Island was unique in one respect. Most of it was owned by absentee landlords in Britain, who were as unpopular as their counterparts in Ireland. By 1836 a popular movement led by William Cooper* was demanding that they be dispossessed for not fulfilling the original conditions of their grants. Although the leaders of the Escheat party hoped to achieve their goals without violence, they encouraged tenants to withhold rents. As in Ireland, the efforts of the government to enforce laws which were considered unjust would lead to civil disobedience and ultimately to retaliation against the property of the landlords and their agents. Yet the pressure upon the government to enforce the collection of rents was growing stronger in Britain. Many of the original grants were passing into the hands of land speculators, who were able to purchase lots at low prices, or were now managed by agents in England and Scotland determined to secure an income from estates long ignored. Conscious that the rising tide of immigration to British North America was increasing the value of colonial properties, and frequently involved in land speculation elsewhere, these men were not interested in the prestige that the possession of large estates might bring but in maximizing profits. Led by David and Robert Bruce Stewart, two London merchants who had purchased large tracts of land on the Island, and by the agents of some of the largest proprietors, such as William Waller and Andrew Colvile, they organized the Prince Edward Island Association to act as a lobby in London.

Before departing for the Island in July 1836, Harvey met with representatives from the association who assured him that, if the escheat issue were resolved, they would deal leniently with their tenants and invest more capital in the colony. But, as Harvey discovered upon his arrival on 30 August, the escheat movement was gaining momentum. Because of an early frost, the Island’s potato crop partially failed in September and the distress thus occasioned, as well as a shortage of hard currency, strengthened the resolve of the tenants. Although Harvey optimistically predicted that he could restore the Island to “a state of perfect tranquillity,” an escheat meeting in Kings County attracted 1,300 people. At Harvey’s request the colonial secretary, Lord Glenelg, prepared a dispatch ruling out escheat and Harvey published it in October. But on 20 Dec. 1836 another mass meeting was held at Hay River, attended by Cooper and two other mhas, John MacKintosh* and John Windsor LeLacheur. The meeting not only demanded escheat but encouraged the tenants to withhold their rent.

This meeting convinced Harvey that more vigorous measures had to be taken to open “the eyes of the deluded Tenantry.” He dismissed from office the magistrate who had chaired the meeting and stripped Cooper of several minor governmental posts. But Harvey placed his greatest faith in the assembly, which was dominated by an élite sympathetic to some of the complaints made against the proprietors but also determined to uphold the rights of property. Working through the speaker of the house, George R. Dalrymple, and councillors Thomas Heath Haviland* and Robert Hodgson*, two of the Island’s most influential politicians, Harvey persuaded the assembly to adopt a series of resolutions condemning the Hay River meeting. Indeed, in its enthusiasm it committed the three mhas who had attended the meeting to the serjeant-at-arms and they remained in custody for two full sessions until the assembly was dissolved. Publicly Harvey predicted that these measures would lead to a “moral revolution” and claimed that the question of escheat had been “settled & forever.” Privately he confided that by arresting Cooper and his fellow escheators the assembly might turn them into martyrs. Harvey quickly realized that the escheat issue would not disappear so easily. In March 1837 he prepared a dispatch requesting permission to establish a special commission to discover which proprietors had not fulfilled the conditions of settlement imposed in 1826. Although he did not send it until the eve of his departure in May, rumours that he was in favour of at least partial escheat circulated freely on the Island.

The major reason why Harvey delayed his dispatch was his desire to convince the absentee landlords that the escheat agitation would end if they offered more lenient terms to their tenants. He had toured much of Prince Edward Island in 1836 and what most impressed him was “how exact an Epitome this Island in some respects is, of the Island . . . which I have so recently left.” Because the proprietorial system diffused settlement and large blocks of wilderness lands hindered development, communications on the Island were primitive. Many landlords would give only short leases and would not compensate tenants for improvements. Rents were high and frequently had to be paid in hard currency, which was in short supply. Thus many tenants owed substantial arrears which they could never hope to pay. Moreover, the Island élite, many of whom owned property or were agents of the proprietors, had limited sympathy with the absentees, who contributed little to development in the colony. Harvey was opposed to the “extreme & unjust Proposition of extinguishing vested Rights for the non fulfillment of impracticable conditions,” but he admitted that his ideas had “undergone some change since my arrival here” and he supported the introduction of “a very moderate ‘Penal Assessment’” on unsettled lands to raise funds for internal development. He also appealed to the landlords in February and March 1837 to grant longer leases with lower rents, to accept the payment of rent in kind, and to abandon the arrears already due. To a friend he had written in January 1837: “Between the Proprietors & the tenants I have had a somewhat difficult card to play but I hope to satisfy both.”

This was a noble objective, but impracticable. Although the assembly passed the Land Assessment Act in April 1837, the proprietorial lobby in London delayed its implementation until 12 Dec. 1838. They also did not respond to Harvey’s request to deal leniently with the tenantry. In fact, several proprietors announced in March 1837 their determination to force the tenants to live up to the terms of existing leases. Harvey considered this action “illtimed & premature,” yet he was bound to enforce their legal rights. Anticipating violence, he asked that the garrison on the Island be strengthened. In his dispatches Harvey continued to give the impression that the Island was basically tranquil, and it is true that while he remained in the colony he was able to maintain order. But the failure of the proprietors to follow Harvey’s advice inevitably aided Cooper and the Escheat party. By May 1837, to take the initiative out of the hands of Cooper, Harvey had decided to send the dispatch recommending partial escheat.

Of Harvey’s influence over the assembly there can be little doubt. Among the numerous measures passed during the 1837 session at Harvey’s request were not only an act levying a moderate assessment on all land in the colony to be used to erect a public records repository, but also bills to create a more effective system of elementary education and to improve the administration of justice. None the less, Harvey overestimated his influence on “the honest, warm-hearted, simple minded People of this Island.” Far from disappearing, the escheat agitation continued to gain momentum and Cooper’s party would form the majority in the next assembly. Fortunately, Harvey did not have to witness this event. He was promoted to New Brunswick and on 25 May 1837 he left Prince Edward Island, to be replaced by Sir Charles Augustus FitzRoy.

On the surface the turbulence of New Brunswick politics resembled that elsewhere in British North America during the 1830s; in reality, the struggle was one for power and place between different factions within the provincial élite. Harvey’s predecessor, Sir Archibald Campbell*, had distributed patronage almost exclusively to a handful of the colony’s leading families, mainly resident in Fredericton and mainly members of the Church of England. He had thus created a bureaucratic élite at least as inbred as its counterpart in Upper Canada in the 1820s. But the Upper Canadian élite was motivated by ideological considerations that simply were not present in New Brunswick, where the politically articulate population was relatively homogeneous in ethnic background and in social and political attitudes and united in its commitment to the imperial connection. Since New Brunswick was divided into a series of communities, each of which was concerned to advance its own immediate self-interest, factionalism was endemic, but party divisions were therefore slow to develop and political rivalries were muted by the existence of a consensus upon fundamental principles. None the less, those excluded from official patronage or resentful of government policies did combine in the mid 1830s to form a coalition that controlled the assembly. Led by the wealthy timber merchants and by the representatives of the dissenting interests, including Charles Simonds, they demanded control over the rapidly increasing crown revenues and over the policies of the Crown Lands Office, headed by the immensely powerful and equally unpopular Thomas Baillie*. When the reformers succeeded in convincing the British government of their moderation and extracted from Glenelg a series of major concessions, Campbell proffered his resignation.

Harvey, as historian James Hannay* has noted, was “a man of a very different spirit” from Campbell. Although basically conservative, Harvey’s patron Anglesey was a member of the Whig ministry and Harvey recognized that the winds of change were sweeping across Britain and into British North America. In 1837 he warned an old friend in Upper Canada, Solicitor General Christopher Alexander Hagerman*: “You deceive yourself – the spirit of real, downright, old Style Toryism being extinct, dead, defunct, defeated and no more capable of revisiting the Nations of the Earth than it is possible for the sparks to descend or the stream to flow upwards.” While on Prince Edward Island, Harvey had applauded the “equitable, just & liberal principles, upon which the Colonial Policy of England is now happily conducted” and had criticized the “anomolous & defective composition” of the Island’s Legislative Council. Immediately upon his arrival in Fredericton on 1 June 1837 he embarked upon the policy of conciliation that Campbell had refused to implement. In July he hastily convened the assembly to present it with a bill surrendering the revenues of the crown for a permanent civil list. He also sought to end “the dissatisfaction which has long & I fear so justly prevailed, throughout the whole colony, regarding the conduct & management of the Crown Land Department.” But although he was able to limit “the undue, uncontrolled, almost irresponsible Financial Powers” exercised by Baillie, he could not suspend him from office until 1840, after Baillie had become insolvent. Indeed, Baillie’s refusal to retire upon terms that the assembly would accept was the one issue that threatened to disrupt Harvey’s harmonious relationship with the house.

This harmony was based on more than just the concession of crown revenues and the reorganization of the Crown Lands Office. Adjustments were necessary in the personnel of the government to place power in the hands of those having the confidence of the assembly. In New Brunswick, since the challengers resembled the existing ruling class in background and attitude, all that was required was the distribution of patronage upon a less exclusive basis. Thus Harvey appointed a number of reformers as justices of the peace and he selected “men of Liberal opinions” such as Lemuel Allan Wilmot* and William Boyd Kinnear* as queen’s counsels “for the purpose of counter ballancing the Barristers of opposite Politics who had been previously preferred.” He also expanded the Legislative Council to include those speaking for the “Dissenting Interests” and areas of the colony long underrepresented. Among the latter was the city of Saint John. Unlike many of the aristocratic and military governors of the 1830s Harvey did not look down upon commercial men. He sought to ally his government with the entrepreneurial leaders of the colony and frequently visited Saint John and promoted urban reforms.

Harvey’s most important decision, however, was to bring into his Executive Council the leading figures in the assembly, especially Simonds, the speaker of the house. It is frequently asserted that Harvey established a form of responsible government in New Brunswick. If one uses that term in its broadest sense, as it had been used in Britain for more than a century, then Harvey did indeed introduce into New Brunswick, as historian William Stewart MacNutt* has claimed, “the essential ingredients of the British system, an executive responsible to the elected representatives of the people.” But this was not responsible government as it was later understood. Harvey did not turn the Executive Council into a cabinet of ministers and he did not feel that he had to follow the advice he was given. Neither Harvey nor his superiors in London wished to introduce into the colony a system of party government similar to that which had evolved at Westminster by the early 19th century. The New Brunswick assembly clearly indicated in its resolutions of 29 Feb. 1840 that it wanted “an efficient responsibility on the part of the Executive officers to the Representative Branch of the Provincial Government,” but in the absence of a coherent party system there could be no demand for party government. Harvey’s Executive Council was thus a coalition of the leading political figures in the colony, who felt free to disagree among themselves. The absence of parties allowed Harvey to initiate policies and to control patronage.

Although Harvey did not intend to exclude from his Executive Council the leaders of the old official party, their stubborn resistance to his policies left him little choice. William Franklin Odell*, George Frederick Street, and Baillie, all interrelated by marriage, were sufficiently influential in Fredericton to be able to embarrass the lieutenant governor on several occasions; he therefore welcomed the arrival of Lord John Russell’s famous dispatch of 16 Oct. 1839 announcing a change in the tenure of public office in the colonies and circulated it to the leading officials in New Brunswick. Those opponents of his régime whom he could not conciliate, he could now at least silence.

Yet, as Harvey clearly understood, there were distinct limits to his authority and influence. One of the fundamental principles to which the members of the assembly were committed was their right to decide how the provincial revenues would be distributed and they would support the government only upon this condition. Undeniably, this system could be abused and to a considerable extent the colony’s financial resources were frittered away on purely local projects. But Hannay was right to stress that “a glance at the statute books [during the Harvey years], discloses the fact that there was great activity in many lines of enterprise.” Much of this activity was in response to private or local pressures and frequently served merely to advance the interests of a particular community, a specific interest group, or even an individual entrepreneur. None the less, this decentralized system made sense in a colony divided by geography into a series of distinct communities which had little contact with one another. Harvey’s successor, Sir William MacBean George Colebrooke*, would discover in the 1840s that he could not artificially create a provincial mentality. Until the railway era, perhaps even later, such a mentality did not exist, at least outside limited circles in Fredericton and Saint John. In any case, a system of party government and executive centralization, as the history of the Canadas in the 1850s shows, would not have prevented the government from becoming the agent of particularistic interests in an age when the pursuit of private gain was considered the most effective way to advance the public interest. Brokerage politics was an inevitable development in a pre-industrial society where the scope of government was extremely limited and the vast majority of the population was only intermittently affected by government activities. To criticize Harvey, as MacNutt has done, for acquiescing in the uncontrolled expenditures of an assembly “whose political horizons were for the most part limited by the parish pump” is to apply anachronistic standards. Indeed, by yielding to pressures which were too strong to resist, Harvey did help preserve a respect for the imperial authority that to a limited degree would persist into the industrial era. During his administration he initiated or supported, with varying degrees of success, major reforms in the colony’s legal system, revisions in public and higher education, improved communications, the first geological survey of the province, by Abraham Gesner*, the development of agriculture, a revitalized militia, and an improved system of support for paupers and the insane. These objectives he was to pursue in all the colonies in which he served.

Much of Harvey’s time was devoted to military affairs. Within 24 hours of his arrival he was embroiled in the Maine–New Brunswick boundary dispute by the arrest of Ebenezer Greeley, a census taker from Maine who had been working in the territory claimed by the British government. With Maine threatening to retaliate by occupying the disputed area, Harvey sent troops to Woodstock and Grand Falls and personally visited the area. His main objective was to deter American encroachments before they led to a confrontation that would engulf Britain and the United States in another war. Although the possibility of conflict receded during the autumn of 1837, the following spring Maine renewed its efforts to establish control over the area. Harvey was now placed in an awkward position. Because of the rebellions in the Canadas, New Brunswick was denuded of troops, and he was forbidden by Sir Colin Campbell*, military commander for the Atlantic region, from stationing troops, when they did arrive, in positions above Fredericton on the Saint John River. Yet between December 1837 and the spring of 1839 Harvey was responsible for conveying overland five regiments and two companies of British troops to Lower Canada, and the security of the route became his major concern. For this reason he sought to reduce tensions with Maine by releasing Greeley from prison, entering into a personal correspondence with the governor of Maine, John Fairfield, and turning a blind eye to Maine’s encroachments into the valley of the Aroostook River. In March 1839, however, Harvey decided that another show of strength was necessary and re-established a British force in the disputed territory, but he warned the officer in charge to retreat at the first sign of real danger. He eagerly assented to an agreement with the governor of Maine, negotiated by General Winfield Scott representing the American federal government, to withdraw the force if Maine would remove her troops.

By these actions Harvey prevented the “Aroostook war” from evolving into a serious confrontation at a moment when Britain was ill equipped for one. Harvey’s personal prestige was never higher than during this period. Not only had he pacified New Brunswick but the colony volunteered men and money to put down the Canadian rebellions. Harvey was in charge of the New Brunswick mission to meet with Lord Durham [Lambton*] in 1838, the year in which at long last he received his kcb, and he was fulsomely praised in the Durham report. Charles Edward Poulett Thomson*, later Lord Sydenham, visited New Brunswick in 1840 and described Harvey as “the Pearl of Civil Governors.” Although his relationship with Sir Colin Campbell had gradually deteriorated into open hostility, Harvey had persuaded the military authorities in London to give him command of the troops in New Brunswick in July 1837, to place him on the staff as a major-general in November, and to grant him the pay and allowances of his rank in November 1839. In September 1840 Harvey replaced Campbell as commander of the troops in the Atlantic provinces and moved the headquarters to New Brunswick.

Harvey’s personal affairs were on a more secure basis in the late 1830s. In Ireland he had gone into debt, in Prince Edward Island his salary had not been sufficient to meet his expenses, and shortly after his arrival in New Brunswick he had been forced to negotiate a loan from the Bank of British North America. But owing to the generosity of the New Brunswick legislature, which not only increased his salary but also made special grants for the upkeep of Government House and for a private secretary, and to the allowances and patronage attached to the military command, Harvey was on his way to solvency. Since he had no estates, he had provided for his sons in the only way that he could, by securing them commissions in the army and the navy. With considerable military patronage at his disposal, he was able to reunite his family under his roof in Fredericton. His only daughter married his aide-de-camp in 1839 and they lived at Government House. The death of his eldest son, on 22 March 1839, was the only tragedy to mar what Harvey would afterwards recall as the happiest years of his life.

Yet Harvey had already set in motion the train of events that would lead to his recall. He believed that the agreement with Maine would serve to maintain the territorial status quo until the British and American governments could reach a final settlement of the boundary. But negotiations moved slowly during 1839 and 1840 and Maine gradually extended its authority in the area under dispute by building roads and establishing new settlements. Although Maine had agreed in March 1839 to withdraw its troops from the disputed territory, it retained an armed civil posse which established a small base at the mouth of the Fish River during the summer. These actions did not break the 1839 agreement, but they were clearly contrary to its spirit, and Harvey gradually came to realize that he had underestimated Maine’s determination and had signed an agreement which left the initiative in its hands. In November 1840 Harvey decided that Britain must reassert her authority and he asked Sydenham to dispatch a substantial force to Lake Temisquata (Lac Témiscouata, Que.) on the edge of the disputed territory. After reconsidering this request, Harvey appealed to Sydenham to rescind the order but the troops were already on the march. Foolishly, Harvey then assured the governor of Maine that they would soon be withdrawn. For this indiscretion he was dismissed by Lord John Russell, the British colonial secretary, who was persuaded by Sydenham and by a bellicose Lord Palmerston, the foreign secretary, that Harvey’s action would encourage Maine’s transgressions.

For once, Harvey had totally misjudged the political situation. With Canada pacified and with an enormous British force stationed in the North American colonies, the balance of power, at least temporarily, had shifted in favour of Britain and the British government was determined to force the United States to agree to a negotiated settlement of the boundary dispute. Harvey did not realize until too late that his policy of appeasement was no longer in line with government policy. When the overseas mail arrived in Fredericton in February 1841, the first letter that Harvey opened was from his friend Sir Charles Theophilus Metcalfe* predicting that Harvey would some day be appointed governor of Canada. The second letter was from George W. Featherstonhaugh, another friend, who had been deputed by Russell to inform Harvey of his dismissal. The blow, being quite unexpected, came as a tremendous shock to Harvey and his family. He had good reason to despair. Without a private income, he would be ruined. Fortunately, his advocate, Anglesey, persuaded Russell to appoint Harvey to Newfoundland in April 1841.

After a brief visit to London, Harvey arrived in Newfoundland in September 1841. Both before and after the introduction of representative government in 1832, Newfoundland politics had been disrupted by sectarian animosities and by bitter disputes between the wealthy merchants of St John’s, who were frequently transients, and the representatives of the rapidly growing resident (native) population, which was engaged in the fisheries. Harvey’s predecessor, Henry Prescott*, had sought to mediate between the rival factions in the colony, but had succeeded only in dissatisfying virtually everyone. During the general elections in November and December 1840 this dissatisfaction led to considerable violence and when the Newfoundland legislature met in 1841 the assembly and the council disagreed over nearly every measure, including the annual supply bill. By the autumn of 1841 the British government had reached the conclusion that substantial changes would have to be made in the constitution of Newfoundland and, while considering the nature of the reforms to be introduced, it suspended the existing constitution. To some extent these developments worked to Harvey’s advantage. Many of Newfoundland’s political and religious leaders had been shocked by the escalation of violence and were prepared to cooperate, at least for the moment, with a governor who sought to heal old wounds. Harvey, as the members of the St John’s Natives’ Society noted, had already established a reputation as a “political physician” and James Stephen at the Colonial Office believed that he was “more likely than any man I know to allay the storms which have so long agitated Society in Newfoundland.” None the less, the traditional enmities in island politics had not disappeared and Harvey’s task was a formidable one.

Potentially the most disruptive force in Newfoundland, as elsewhere in British North America, was religion. Given his background, it is hardly surprising that Harvey was a committed supporter of the Church of England. Indeed, he conscientiously attended services, gave generously from his meagre private resources, and consistently sought to advance the church’s interests. His sympathies lay with the low-church party and he formed a close friendship with Aubrey George Spencer*, the bishop of Newfoundland, a friendship cemented by the marriage of his youngest son to one of the bishop’s daughters. Harvey assisted the bishop in acquiring the land upon which a cathedral was eventually erected in St John’s. In both Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick, while actively supporting the Church of England, Harvey had, however, endeared himself to dissenters by extending government patronage to their institutions. He was less successful with the various Protestant sects in Newfoundland. In 1843 an education bill was introduced in the assembly by Richard Barnes*, member for Trinity Bay, which provided for an equal distribution of funds between Catholic and Protestant elementary schools. Harvey strongly supported the bill, but only with great difficulty was he able to convince the dissenting sects that it did not unduly favour the Church of England schools. Harvey also aroused the suspicion of the dissenters by appointing Bryan Robinson*, an outspoken advocate of the Church of England, to the Executive Council in 1843. Robinson, a prominent lawyer, had become involved in a bitter personal controversy over the functioning of the Supreme Court with Chief Justice John Gervase Hutchinson Bourne*, and Harvey became unavoidably entangled in the dispute when he sought to mediate between the two men. Harvey ascribed Bourne’s refusal to abandon the controversy to the chief justice’s alliance with “a certain party of Dissenters” who bitterly assailed “our venerable Church establishment.”

Harvey maintained his efforts on behalf of the Church of England, but in 1844 he supported the founding of an academy which would be free of religious instruction and in 1845 he advocated a policy of assisting all religious groups in the construction of churches. These policies were frustrated by Spencer’s successor, Edward Feild*, who had high-church leanings. In New Brunswick, Harvey had vainly tried to liberalize the charter of King’s College, Fredericton; in Newfoundland, too, he was unable to convince his co-religionists of “the mischievous consequences of clothing Educational institutions with too exclusive a character.”

These difficulties were overshadowed, however, by the problem of convincing the colony’s Roman Catholics of the good intentions of the government. Prescott had entered into a vitriolic debate with Bishop Michael Anthony Fleming* and had alienated almost the entire Catholic population. Like most of his contemporaries, Harvey was suspicious of the Catholic Church in general and of non-Anglo-Saxon Catholics in particular. While serving in Prince Edward Island, he had attempted to prevent the appointment of an Irish or French Canadian Catholic to a vacant bishopric, because their clergy “meddle too much with Politics.” He also subscribed to the popular stereotype that the Irish were excitable and easily misled by their religious leaders. None the less, having seen both in the Canadas and in Ireland how discrimination and bigotry led to religious and political conflicts, he had actively and consistently sought the cooperation of Catholic clergy in Ireland, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick.

From the moment of his arrival in Newfoundland in September 1841 Harvey sought to end sectarian conflicts and conciliate Catholics. As an initial “act of leniency,” he released several prisoners arrested during the election riots of the previous December and he withdrew the garrison stationed in Carbonear. He then secured a promise from Fleming to withdraw from politics, a promise which the bishop kept. Harvey’s share of the bargain was to administer the government impartially and this promise was also kept. Despite Protestant outcries, he appointed the first Catholic magistrate in St John’s. In December 1842 he censured a Protestant magistrate for arresting the prominent Catholic politician John Valentine Nugent* during an election. Harvey wanted the Education Act of 1843, which placed Catholics and Protestants on an equal footing in the distribution of funds, to include provision for both a Catholic and a Protestant inspector of schools. When the assembly made provision for only one position, he alternated the appointment on an annual basis. His Executive Council was “composed fairly & impartially of Protestants & Catholics.” According to Catholic politician John Kent*, Harvey’s “conciliatory conduct & strict impartiality” persuaded leading Catholics William Carson*, Laurence O’Brien*, and Patrick Morris* to serve on this council. Even when some of them attended an Irish repeal meeting in St John’s, and thus incurred the censure of the British government, Harvey defended their actions in July 1844 in his report to the Colonial Office.

Catholic support was critical for Harvey. The constitution introduced in 1842 by the Newfoundland Act, partly at Harvey’s request, had been imposed against the wishes of the Catholics who dominated the reform party. Harvey realized that without reform support the amalgamated legislature of 15 elected and 10 appointed members would work no more efficiently than the old. Although he had encouraged the Colonial Office to try the experiment, he indicated to the reform leaders that it was to be only a temporary expedient. In theory, under the new constitution, the lieutenant governor, by controlling the initiation of money bills, would be able to exert a commanding influence upon the development of the colony. In practice, Harvey allowed the members of the Amalgamated Legislature to distribute the funds according to their perception of the requirements of the colony. Under these conditions the reformers were prepared to assist in making the legislature work. By 1846, however, even Harvey could not persuade the reformers to accept a renewal of the amalgamation bill when it was to expire the following year. In February 1846 the legislature voted by ten to nine for a series of resolutions, moved by Kent, advocating responsible government. Nine of the ten votes in favour were by Catholics and the tenth was by a Protestant dependent upon Catholic support. None the less, even Kent remained ready to defend Harvey’s administration.

More remarkable is the fact that Harvey consolidated Catholic and reform support without antagonizing the Conservatives, whose leadership was drawn largely from the Protestant, mercantile community of St John’s. Along with its rural areas the city represented nearly 40 per cent of the island’s population, and Harvey quickly realized that he had to show its leading citizens they could expect concrete improvements from his government. During his tenure of office he vigorously supported the ambitions of the St John’s Chamber of Commerce by advocating more efficient postal service and steamship communications with the outside world and by protesting “the French invasion of our Fisheries.” He also sought to improve the appearance of St John’s and the quality of health and public services within the city. It is ironic that in his efforts at beautification he may have contributed, by removing some of the natural fire-breaks, to the damage caused by the great fire of June 1846, which “suddenly swept away three fourths of this so lately wealthy and prosperous City.” By appointing the candidate of the St John’s Chamber of Commerce, William Thomas, to the Executive Council in 1842, by consulting frequently with the merchants, and by devoting himself “heart and soul to the local and general improvement of the country,” Harvey reconciled the merchant éIite to the reintroduction of the old representative system. “His Excellency arrived amongst us,” Charles James Fox Bennett* proclaimed in 1846, “at a period when the country had been torn and distracted by political animosities, when disorder and confusion had reigned on every side, and when the framework of our political existence had been disjointed and severed; but no sooner had he placed his foot upon our shores than he, as if by the touch of a talismanic wand, restored order, peace and happiness to the country.”

This claim is exaggerated. Harvey had no magic wand, and he could not make ethnic, religious, and socio-economic rivalries disappear. None the less, whenever the opportunity presented itself, he sought to persuade the various groups within the community to focus upon the issues that united rather than those that divided them. He founded Newfoundland’s first Agricultural Society at St John’s in 1841, partly to provide an association. to which both Catholics and Protestants could belong. He attempted to persuade the religious leaders of both to unite in a temperance crusade in 1844, and he became patron of the Natives’ Society because he felt it was an organization that promised to transcend other loyalties. Yet many Protestants bitterly resented Harvey’s efforts to distribute patronage to Catholics, and reformers and Conservatives remained at odds over the direction in which the colony should develop. Harvey did not remove the sources of friction, but he did create an atmosphere in which differences of opinion could be resolved peacefully.

Despite this achievement, Harvey did not enjoy his sojourn in Newfoundland. Like his close friend Sir Richard Henry Bonnycastle*, he found the “siberian” winters nearly unbearable. He was also plagued by financial difficulties. His sudden removal from New Brunswick had occurred before he had paid off his debts and it left him virtually destitute. He had already disposed of most of his household effects in New Brunswick at a heavy loss before he learned of his appointment to Newfoundland and he had had to request an advance to meet the charges on his commission and to purchase Prescott’s furniture. The annual salary of £3,000 was £1,000 less than in New Brunswick, St John’s was an expensive city in which to live, and Government House was costly to maintain. Shortly after his arrival in the colony, the Bank of British North America demanded payment of his outstanding debts and Harvey was compelled to borrow money from his colonial secretary, James Crowdy*. During the prolonged controversy with Bourne, this arrangement was brought to the attention of the Colonial Office. Ultimately, Harvey was exonerated of any wrongdoing, but he was reprimanded for indiscretion. It is not easy to feel much sympathy for a man who earned more in a year than most labourers could earn in a lifetime, who travelled with a retinue of servants, and who entertained lavishly. But Harvey must be judged by the standards of the age in which he lived. He was expected to maintain a standard of living which, without a private income, he simply could not afford, and “the exercise of hospitality” was, as he claimed, one of the means by which a governor cultivated a “good understanding” in a colony. He did give generously to charities and other worthy causes. If he lived beyond his means and engaged in activities that justifiably led to charges of conflict of interest, he really had little choice.

It was more than harsh climate and financial worries that led to Harvey’s dissatisfaction. His youngest son fell ill in Newfoundland and died early in 1846. His other sons were forced to seek employment elsewhere and his daughter was with her husband in Halifax. Harvey wished to reunite his family under one roof, and when the lieutenant governorship of Nova Scotia became vacant he eagerly applied for it. With almost unseemly haste, and to the consternation of the Colonial Office, he departed from Newfoundland in August 1846 as quickly as he could after receiving the appointment.

When Harvey arrived in Nova Scotia late in August 1846, he was hailed by the Yarmouth Courier as the man who could “check that spirit of discord which has been rife throughout this province for some years.” Certainly Harvey hoped that by applying to Nova Scotia the methods that had worked so successfully elsewhere he could restore “this distracted Province to that condition of political & social tranquillity which I really believe to be desired by all”. But those methods had only limited success in Nova Scotia. Both the Conservatives and the Liberals were now relatively cohesive political parties. Although the Conservatives had a majority of seats in the house, Harvey sought to create a calmer political atmosphere than the one he had inherited from his predecessor, Lord Falkland [Cary*], who had ostracized the leading Liberals and identified himself with the Conservatives [see George Renny Young]. By friendly gestures to the leaders of the Liberal party and by inviting “the influential of all parties” to dine at Government House, Harvey succeeded in reducing tensions.

Yet, despite repeated efforts, Harvey could not persuade the Liberals that they should join with the Conservatives in a coalition government. Indeed, so confident were the Liberals of success in the approaching election that they only reluctantly abandoned their demand for an immediate dissolution and agreed to refrain from obstructing the final session of the legislature in 1847. Although these concessions in themselves represented a major victory for Harvey, they did not result in the formation of a coalition. Harvey’s failure led Earl Grey, who had recently become secretary of state for the colonies, to enunciate in two important dispatches his willingness to accept party government in the larger British North American colonies. But Harvey continued to hope that he could bring about “a fusion of parties” in Nova Scotia after the forthcoming general election.

On 5 Aug. 1847 the Liberals were victorious at the polls. After a final, but unsuccessful, effort to construct a coalition, Harvey was left with no option but to accept the first administration based on party in British North America. But until the assembly met in January 1848 and carried a vote of non-confidence by a margin of 29 to 22, Harvey had to carry on with a government that refused to resign until the house had pronounced its verdict. During this period he was able to persuade the Conservatives not to recommend appointments that he could not approve and the Liberals to restrain their impatience for office.

The transfer of power formally took place on 2 Feb. 1848, when James Boyle Uniacke became premier of “the first formally responsible ministry overseas.” But the transition was neither as simple nor as harmonious as many historians, particularly Chester Martin*, have implied. A rudimentary system of cabinet government had been introduced into the Province of Canada in 1841, but in Nova Scotia the Executive Council did not consist of officials holding ministerial positions and the Liberals were determined to restructure the council into a cabinet of ministers. Harvey thus had to force into retirement the provincial secretary, Sir Rupert D. George, who had held office for 25 years, and to dismiss Samuel Prescott Fairbanks*, who had been appointed provincial treasurer for life in 1845. He also agreed to the creation of several new ministerial posts. Lord Grey had already agreed to the principle of responsible party government, but he had hoped to limit to the barest minimum the number of ministerial positions that would change, and he was only reluctantly persuaded by Harvey of the necessity of converting the Executive Council into a cabinet on the British and Canadian models.

Harvey sincerely tried to persuade his new advisers to compensate generously with pensions those who were displaced, but he was only partially successful and a stream of petitions were sent to the British government complaining of the changes. The Conservative press in Nova Scotia began to abuse him for yielding to Liberal demands and James William Johnston*, who had been forced to resign as attorney general, moved a resolution in the assembly to reduce the lieutenant governor’s annual salary from £3,000 to £2,500. The crown revenues in Nova Scotia had not been surrendered for a permanent civil list and the Liberals had frequently condemned the high salaries paid to officials, many of whom were owed several years’ arrears because of the inadequacy of the crown’s revenues. Johnston’s motion was designed to embarrass both the lieutenant governor and his advisers and the government hastily introduced a civil list bill which gave Harvey £3,500 per annum (£1,500 more than his successors were to receive), reduced the salaries of most other officials, and disallowed the arrears that had been accumulating since 1844. To Harvey’s dismay Lord Grey refused to assent to the act and reprimanded Harvey for placing his own claims before those of other officials who were owed arrears or whose salaries had been reduced. Although Harvey ultimately persuaded the Liberal government to agree to Grey’s terms, he was forced to abandon his claim to a higher salary. Harvey felt badly treated, but by foolishly consenting to the initial bill he had brought upon himself Grey’s censure and given credence to the charge that he had “bargained with his Council, to promote his pecuniary interests.”

During 1849 Harvey again became the subject of Conservative criticism when he agreed to a wholesale revision of the commission of the peace. Although it is frequently asserted that the reform ministers of this period withstood the pressure from their supporters for the introduction of the spoils system, in 1849 scores of Conservative justices of the peace were dismissed and several hundred Liberals were appointed. Believing that Harvey had become “a regular partizan of his present advisors,” Grey vigorously protested against the change in the commission. Harvey was able to persuade his ministers to restore some of the dismissed magistrates to office, but he defended his government and correctly pointed out that there were limits to his influence. Party control over patronage was an inevitable concomitant of party government and Harvey at best could moderate the extension of this principle to Nova Scotia. Ultimately, he forced Grey to accept this fact and, without any prospect of Colonial Office support, the Conservatives of Nova Scotia began to adjust to the new system, although the attacks on Harvey continued.

Much of the criticism directed against Harvey was, as he claimed, motivated by nothing more than the frustrations and pique of those dismissed from office, but it is clear that he reacted to the criticism by identifying himself more closely with his Liberal advisers and by relying upon them to defend him in the assembly. Indeed, Harvey did not think that he would be able to remain in Nova Scotia if the Conservatives were returned to office. He also came to play only a minor role in the governmental process. To some extent this was an inevitable development, as his Executive Council increasingly demanded that “the introduction & management” of bills “should be left in their hands.” But Lord Elgin [Bruce*] in Canada and Sir Edmund Walker Head* in New Brunswick were able to show that a governor could continue to influence the course of events, even after the introduction of party government. However, these were men in the prime of health. Harvey was over 70, ill, and by 1850 without much energy to resist or to question the advice he was given. He did espouse a number of important causes after 1848: he was an outspoken proponent of imperial aid for railways, defended the principle of public ownership for both railways and telegraph lines, and promoted intercolonial free trade and British North American federation. But on all these issues his views were largely shaped by others, particularly Joseph Howe*, the colony’s provincial secretary, with whom he formed a friendship that went deeper than mere political convenience.

Harvey suffered a shattering blow when his wife died on 10 April 1851, and his health rapidly deteriorated. On his doctor’s advice he began a six months’ leave of absence in May but, even though his health improved, he was partially paralysed and on his return to the colony in October he was scarcely capable of performing even the routine functions of his office. Pathetically he appealed to Grey to transfer him to a warmer climate, but he was to die in Nova Scotia on 22 March 1852 and was buried in the military cemetery in Halifax beside his wife.

Although Harvey served in more colonies in British North America than any other governor and was successful in all of them, his fame was strangely ephemeral. In part, his fate reflects the central Canadian bias of our historiography. Although he played a conspicuous part in the evolution of the system of responsible government, he worked on the periphery and thus was never accorded the same status as Durham, Sydenham, and Elgin. But there is another reason why Harvey is little known. Most of what has been written about pre-confederation Canada has been Whiggish in approach. From this perspective (the colony-to-nation perspective), governors are interesting only in so far as they produce colonial discontent which leads to demands for autonomy and reform. Thus it is the unsuccessful governors – Sir Peregrine Maitland, Lord Dalhousie, Sir Archibald Campbell – who occupy the centre stage, whereas governors who reduce tensions and minimize conflict are relegated to the wings. And no one performed these tasks better than Harvey. His career belies the cliché that military men necessarily made poor civil governors. Of course, in one critical respect Harvey differed from the other military governors of the period. He came from a family that had neither aristocratic connections nor a tradition of military service and he had no private fortune to fall back on. Harvey was frequently accused of being motivated by personal and financial considerations and these accusations were not entirely unfounded. Yet it would be wrong to dismiss Harvey as a man devoid of principle who governed through what James Stephen, the under-secretary at the Colonial Office, described as “a system of blandishments.” Because his origins were comparatively humble, he did not find exile among the colonists as tedious as did most governors. “Never have I known a man so tolerant, so placid and so affable to all who approach him, high or low, rich or poor,” Bryan Robinson declared in 1846. That was the ultimate secret of Harvey’s success. He was flexible and he was tolerant. He was, as he described himself in one letter, a “Peace maker” and thus the ideal person to govern four colonies during a difficult period.