inscribed dated and signed with signature & monogram "THE- LADY - DOROTHY - NEVILL / October 18 A.D.1912 / George Kruger" and inscribed on 3 labels on the reverse " THE LADY DOROTHY NEVILL/ George Kruger No3 / 124 Cheyne Walk / Chelsea SW / …3rd Earl of Orford / of …creation)/ of Wolterton Norfolk/ B 1826 Died 1913 / Painted by George Kruger / Purchased from the R Academy/ Summer Exhibition 1913/ No 1125 in the catalogue/ C.E.S.C./Aug 26 1913"

Royal Academy Summer Exhibition 1913, No. 1125

Lady Nevill caricatured by "K" for Vanity Fair, 1912

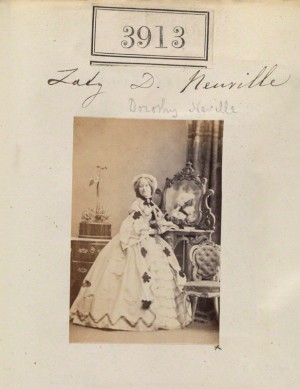

Lady Dorothy Fanny Nevill (1 April 1826 in London – 24 March 1913 in London), was an English writer, hostess, horticulturist and plant collector.

She was one of five children of Horatio Walpole, 3rd Earl of Orford and Mary Fawkener, daughter of William Augustus Fawkener, sometime envoy extraordinary at St Petersburg and close friend of Empress Catherine. She was born on 1 April 1826 at 11 Berkeley Square, London. She was the youngest in the family of three sons and two daughters of Horatio Walpole, third earl of Orford, and his wife, Mary, daughter of William Augustus Fawkener, envoy-extraordinary at St Petersburg. She spent her childhood at the family seats at Wolterton in Norfolk and Ilsington in Dorset, and at the house in Berkeley Square. She received no formal education, but was taught Italian, French, Greek, and Latin by an excellent governess, Eliza Redgrave, sister of the painter Richard Redgrave.

Despite their rank, the Walpoles were on the fringes of society: Lord Orford gambled, and his son Horatio eloped with the notorious Lady Lincoln. Lady Dorothy was introduced to London society in 1846, during the course of which season her name was linked with those of several young men. Her reputation was damaged by rumours, which suggested a liaison with Disraeli's friend and associate George Smythe, In 1847, she was embroiled in a scandal when caught in a summerhouse with the notorious rake, George Smythe MP, heir to a peerage. Smythe refused to marry her, and her parents' actions and statements destroyed her reputation. and she was hastily married to her cousin Reginald Henry Nevill (1807–1878) on 2 December 1847. He was twenty years her senior, and had inherited considerable wealth from a Walpole uncle. He was the son of the Revd George Henry Nevill (the son of George Nevill, first earl of Abergavenny) and his wife, Caroline Walpole. Lady Dorothy and her husband had six children, four of whom (one daughter and three sons) survived to adulthood. Her surviving daughter, Meresia Nevill, became a political agent and, like Lady Dorothy, a prominent promoter of the Primrose League.

In 1847 she married a cousin twenty years her senior, one Reginald Henry Nevill (d. 1878), a grandson of the 1st Earl of Abergavenny and produced six children, only four of whom survived beyond childhood. She travelled extensively and cultivated a large circle of literary and artistic friends, with a sprinkling of politicians, including James McNeill Whistler, Richard Cobden, Joseph Chamberlain and Disraeli, whom she greatly admired. She was however, never received by Queen Victoria.

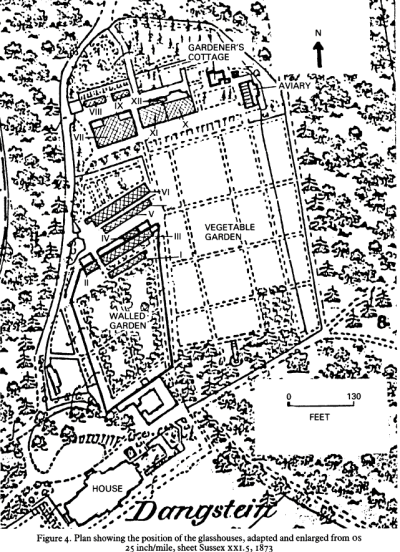

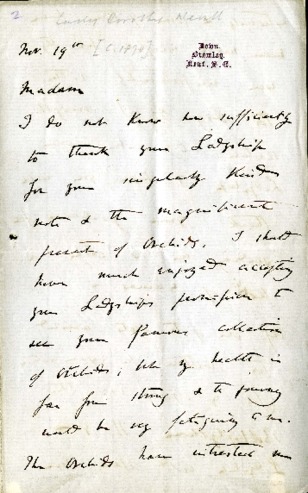

In 1851 the Nevills acquired a large Sussex property, 'Dangstein' near Petersfield. Dorothy Nevill turned the estate garden into a horticultural landmark. Her exotic plants were housed in seventeen conservatories and were the subject of numerous articles in journals on horticulture. Through her plants she became friendly with both William and Joseph Hooker at Kew, and supplied Charles Darwin with rare plants for his researches. Dorothy was particularly known as an orchid grower, leading to a correspondence with Darwin that began in November 1861 when he wrote to ask for specimens to further his research towards his pamphlet on orchids. Nevill was delighted to comply, and was duly acknowledged with a presentation copy. In 1851 the Nevills acquired, in addition to their London house at 45 Charles Street, an estate in west Sussex known as Dangstein, near Petersfield, with a large neo-Grecian mansion, built in the 1830s. Reginald looked after the large estate, while Lady Dorothytook charge of the house and the 23 acre garden. The latter soon became celebrated in horticultural circles, particularly for the collection of exotics, housed in its seventeen hothouses, which were the subject of no fewer than twelve articles in the gardening press. Lady Dorothy soon struck up a friendship with William Hooker at Kew, with whom she exchanged plants and letters; and the relationship continued with his son and successor, Joseph Hooker. She was on friendly terms with most of the leading horticulturists of the time, and was able to provide Charles Darwin with a number of rare plants.

She kept exotic birds and mammals on the estate, farmed silkworms and maintained a museum of her collections. After her husband's death, when he left all his money to their surviving children to curtail her expenditures, she moved to 'Stillyans' near Heathfield in Sussex which she rented from one of her botanical friends Doctor Robert Hogg.

As well as these exotics, the garden at Dangstein, tended by thirty-four gardeners, had one of the earliest herbaceous borders, a pinetum, exotic birds and animals, a flock of pigeons with Chinese whistles attached to their tails (Lady Dorothy's ‘aerial orchestra’), a silkworm farm, and a museum with some of her numerous collections—snuffboxes, corset buttons, silhouettes, wax medallions, lockets, and many similar objects. As well as collecting these trivia, Lady Dorothy was a serious collector of eighteenth-century porcelain and pictures, particularly anything relating to her ancestor Horace Walpole, fourth earl of Orford (1717–1797).

Lady Dorothy's habit of collecting extended to people. Her salon at 45 Charles Street, modelled on that of Lady Molesworth, was eagerly attended by politicians, writers, artists, scientists, and soldiers. Disraeli was a close friend (family tradition held that he was the father of her youngest son, Ralph), and her salon was at its most influential in 1866–8. She was a strong Conservative and founder member of the Primrose League, but her dinner-table was by no means sectarian: Richard Cobden was as likely to dine with her as the second duke of Wellington or the prince of Wales. After her husband died in 1878 she moved to Stillyans, in east Sussex, where she also had a garden, but thereafter most of her entertaining was done in London. In her ‘quaintly episcopal’ robes, she sought out celebrities, entertaining Joseph Chamberlain (with whom she shared a passion for orchids) before his acceptance at other aristocratic tables, and the radicals Joseph Arch and H. M. Hyndman. Eclectic in her collection of guests, she had a deep horror of change, which became more pronounced as she grew older, an aversion which is reflected in her comments on the declining standards of high society.

As well as a book on silkworms, and another on her Walpole ancestors, Lady Dorothywrote (with assistance from her son Ralph) three selective autobiographical volumes: The Reminiscences of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1906), Leaves from the Notebooks of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1907), and Under Five Reigns (1910). She died on 24 March 1913 at her home at 45 Charles Street, London.

She was a noted conversationalist - "The real art of conversation is not only to say the right thing at the right place, but to leave unsaid the wrong thing at the tempting moment." - and leading society hostess, her salons attracting celebrities and politicians. She served on the first committee of the Primrose League and wrote a number of volumes of memoirs:

- Recollections (1906)

- Leaves from the Notebooks of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1907)

- Under Five Reigns (1910)

- My Own Times (1912).

- Mannington and the Walpoles, Earls of Orford (1894)

Lady Dorothy died at her home at 45 Charles Street on 24 March 1913, where a memorial plaque was unveiled on 8 September 1998.

Her son, Ralph Nevill, wrote Life and Letters of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1919). Her daughter, Meresia Dorothy Augusta Nevill (1849–1918), was also a dedicated worker for the Primrose League. She served for many years as treasurer of the Ladies' Grand Council and died in London on 26 October 1918.

“The real art of conversation is not only to say the right thing at the right place but to leave unsaid the wrong thing at the tempting moment.” D.Nevill

Lady Nevill corresponded with many famous people of her time incuding Thomas Hardy.

Nevill’s first letter to Hardy was sent in 1891 after the serial publication of Tess of the d’Urbervilles. In 1892 Hardy gave her a copy of the novel which Nevill valued highly. Her letters indicate that she was one of a number of female readers who wanted to voice their support for Hardy’s honest portrayal of Tess.

It was Lady Nevill’s fondness for Dorset that drew her to Hardy’s work. In Life and Letters of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1919) her son, Ralph Nevill, describes how his mother’s ‘recollections of old-time Wessex rippled as sweetly through her memory as a stream through a pleasant dell. The biography’s depiction of Lady Nevill riding across the ‘wild country’ as a young girl also seems to cast her in the shape of a Hardy heroine.

Beyond their shared love of the landscape, Hardy and Lady Nevill developed an enduring friendship through her enthusiasm for holding salons at her home. An accessible railway link from London to Sussex brought a large circle of writers, artists and politicians, including Disraeli, to Dangstein and Nevill was one of a number of English hostesses who not only entertained the literati but were also writers themselves.

Born in 1826 Dorothy grew up on the Orford’s two country estates, Ilsington in Dorset and Wolterton Hall in Norfolk since their London townhouse had to be sold to pay gambling debts. Her parents took a keen interest in the gardens in both places and her early diaries also records visits well-known seedsmen and nurseries with them.

Wolterton was particularly interesting. Built for Sir Robert Walpole’s brother Horatio, it dates from the late 1720s with formal gardens probably planned by Horatio himself with assistance from Thomas Ripley the architect, Joseph Carpenter of Brompton Nursery and Charles Bridgeman. In the 1820s Dorothy’s father commissioned Humphry Repton’s son, George, to enlarge the house and the landscape gardener William Sawrey Gilpin to ‘modernise’ the gardens. For a full description and history of the garden see our database.

http://www.parksandgardens.org/places-and-people/site/3558/summary

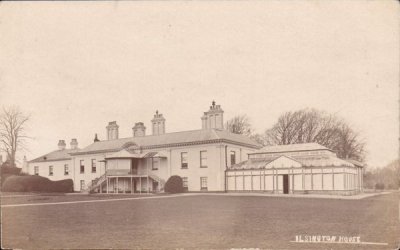

Ilsington House https://twitter.com/nicholaskingsle/status/668716708102848512

Ilsington is a late 17thc grey stone house and apparently had a garden full of topiary. I can’t find much more information about the gardens but the house was sold in 2010 and there is an article about the sale in Country Life at: http://www.countrylife.co.uk/property/country-houses-for-sale-and-property-news/large-dorset-estate-once-owned-by-horace-walpole-22116

Disraeli as a young man, by Francis Grant, 1852 National Trust

Dorothy also saw a lot of European gardens, particularly in Italy and Germany because the Orfords spent a lot of time travelling in her teenage years, largely it would seem to save money. They returned just in time for her to be presented at court, as a debutante, in 1846 and her diary is full of the balls and visits she made that year. At one of these events she met the 42 year old Benjamin Disraeli and they became friends for life.

George Smythe, Viscount Strangford, by R. Buckner, Hughenden Manor, National Trust

It was through Disraeli that she met his closest aide, fellow Tory MP, George Smythe. Whether he pursued her or she him we’ll probably never know but in August that year he followed her to Hampshire where she was staying with her parents. After being discovered one night with him in the summer-house, Dorothy eloped with him to Brighton the next day. It was ten days before she returned. There was soon a report in The Morning Post of “a painful occurrence affecting members of two noble families” and eventually the story hit the scandal press. Dorothy was confined to her room, allegedly recovering from a fall, while the family worked out what to do. The answer was clearly marriage but who would take such spoiled goods? The answer was her much older cousin, Reginald Nevill, grandson of the earl of Abergavenny, and Dorothy looked certain to be condemned to a quiet life of country living and pious good works. If you want to know more about the scandal then Mary Millar’s Disraeli’s Disciple: The Scandalous Life of George Smythe is a good place to start. Luckily the relevant pages are available via Google at:

Fortunately for her, Reginald was, according to Disraeli, “a real good fellow” and helpfully he was also, extremely wealthy. He obviously doted on Dorothy, showering her with jewellery before the wedding, and did not even mind when she took her menagerie of lizards, snakes, tortoises and dogs with them on their honeymoon. Soon they started looking for a country house so that he could indulge his passion for both racing and agriculture, while she could develop her interests in horticulture. They chose Dangstein, an estate of over 1000 acres just over the border of West Sussex from Petersfield in Hampshire. It was considered remote and backward country and still had to be reached by stagecoach.

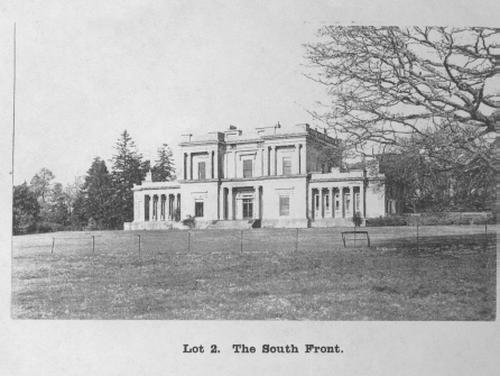

Dangstein, Sussex. South Front of House , nowdemolished. Photo from the 1926 sales details. Image on our database & Copyright: West Sussex Record Office

Dangstein had been built in the 1830s and James Knowles the architect ‘had made an attempt to construct a sort of huge Grecian temple..[but] a great portion of the interior had been sacrificed to afford room for a great central staircase’. The Nevills moved in in 1851 and found it ‘a comfortable house’. In her Reminiscences she noted that “Mr Nevill took a great interest in his estate while I devoted a great deal of time to my garden.”

Plan of Dangstein from the 1873 OS survey. Image from our database http://www.parksandgardens.org/places-and-people/image?id=1935

In fact she approached gardening in a very scientific way, experimenting with what would grow on the sandy loam around Dangstein and as a result the gardens flourished. Over the next four or five years all the accoutrements of a grand Victorian estate garden were put in place. This included a complicated system of using every drop of rainwater, firstly in the glasshouses and conservatories, then the various beds and terraces before it was finally channelled into a bamboo grove at the bottom of the garden. Of course it helped that she had 34 gardeners!

Lady Dorothy began as she meant to continue – in grand style. Workmen began by scooping out dells, ponds, sunken lawns and terraces then tons of earth were imported to level a small valley to the east of the walled garden for growing more vegetables and fruit. Terrace walks and winding broad gravelled paths were laid out to take the visitor around the garden. With the structure in place it was time to plant.

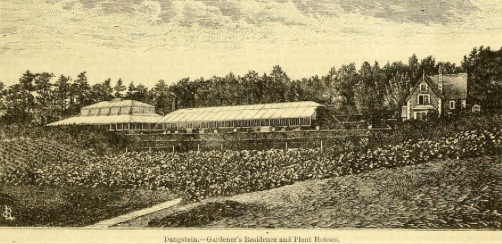

The Gardener’s residence and Plant Houses, from The Journal of horticulture, cottage gardener and country gentlemen, 26th Dec 1872.

Letter from Darwin to Dorothy thanking her for a gift of orchids.

https://digital.case.edu/concern/texts/ksl:ditalldar00219

Lady Dorothy became friends with most of the leading botanists and horticulturists of the day, including Darwin to whom she sent specimens of insectivorous plants. They corresponded about both them and orchids and she visited him at Down House. For more information see: http://www.darwinproject.ac.uk

and for further digitized letters between them see: https://digital.case.edu/ and follow the links to the Stecher Collection of Darwiniana

The Pits as they were c.1988 from Trotter, ‘The glasshouses at Dangstein’ full ref below

But it was the William and Joseph Hooker at Kew that she seemed to get on with best. She was constantly asking for plants and seeds from Kew, sending up her gardener, Mr Vair in his uniform and top hat to collect them.

Guy Nevill in his biography of Lady Dorothy says “she seemed to treat Kew rather like a philatelist does with a competitor’s stamp album; plants were there to be swapped.”

The Peach House c.1988 from Trotter, ‘The glasshouses at Dangstein’ full ref below

The Hookers were invited to Dangstein to see what she was up to and as a result did not seem to resent this. Indeed just the opposite and vol.82 of the Botanical Magazine is dedicated to her.

The result was , as the Morning Chronicle said in , that “every gardener knew Dangstein” and “all make pilgrimages” to see its more than 30 “miniature Crystal Palaces containing more than 40,000 square ft of glass” although they “could not begin to enumerate one hundredth part of the objects of interest” which formed “one of the finest ever amassed by a private individual.”

Of course it was not all plain sailing, and Lady Dorothy recounts a disaster that occurred in one of the hothouses, which highlights the dangers of greenhouse technology of the time. It

Dangstein was not just the home of a great collection of exotic tropical imports. As Lady Dorothy herself said “there were a great many curiosities of different sorts in my garden.” She planted many ‘exotic’ trees and a fashionable pinetum with newly imported redwoods, wellingtonias and monkey-puzzles. The garden also had some of the earliest herbaceous borders in the country, as well as a menagerie, an aviary and a silk-worm farm. The pet’s graveyard she set up came complete with tombstones made from recycling those ‘discarded’ in the ‘modernization’ of the local parish church!

Lady Dorothy by Camille Silvy, albumen print, 25 May 1861, National Portrait Gallery

She collected china and works of art, both the serious and fashionable but also the unusual and the more ephemeral – everything from snuff-boxes and silhouettes to wax medals and corset-buttons – creating a museum to house them. Her collection of old Sussex ironwork, much of it discarded by her farming neighbours, has ended up at the V&A.

Perhaps the most amusing of her collection gives the title of this post. It was her aerial or winged orchestra.

If you don’t believe me [or Lady Dorothy] then check out these recent stories and video clips about pigeon whistles and their sounds!

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2014/aug/22/pigeon-whistles-the-closest-thing-to-heaven

W.Trotter, her biographer for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, says that “Lady Dorothy’s habit of collecting extended to people” with her earlier disgrace pushed into the shadows as she established herself as a society hostess. She held regular salons at their London house in Mayfair which attracted not just politicians but writers, artists, scientists, and soldiers. Chief amongst her regular guests was Disraeli – indeed he was so close a friend that according to family tradition, Disraeli was actually the father of Ralph, her youngest son. She was later to help found the Primrose League in his honour. Although she was an ardent Tory her friendship extended across the political divide and entertained Radicals and Liberals as well as the Prince of Wales and prominent conservatives like Joseph Chamberlain. This was often because of shared horticultural interest.

Postcard of Joseph Chamberlain’s Orchid House at Highbury | by Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

Chamberlain, for example, was renowned as an orchidist and his gardens and hothouses which she visited often, were, she said, ‘a delight’. It was through Cobden that she obtained ‘a special sort of silkworm’ which fed on the Tree of Heaven, Ailanthus glandulosa. Her experiences with the normal mulberry eating silkworm were less than satisfactory. They were kept in the house but ‘occasionally…strayed about and got up people’s trousers, much to their inconvenience and horror.’ These were sent over from the Jardin Imperiale d’Acclimitation in Paris, and flourished so well that she was able to have a dress made from their silk. However the moths did not last long because they became a favourite snack of flocks of the small birds in her garden!

Reginald Nevill died in 1878. “He was so very kind to me” she told a friend. “When he died I wondered how I could go on living without him” and then added “but you see I have!” In fact he was not so kind financially after his death. Most of the property was left to their children while she was left an annuity of £2000 a year which as Guy Nevill comments “effectively put a stop to extending the exotic groves” of Dangstein.

from The Morning Post – Wednesday 12 March 1879

As a result although she maintained the Mayfair house, Dorothy had to move from Dangstein which by then had probably the best collection of exotic plants in Britain outside Kew. She could not afford the cost of their upkeep even if she had somewhere to house them so about 15,000 were auctioned off. The estate sold for £53,000.

Inside the greenhouse complex at Laeken Palace, Nr Brussells. https://www.monarchie.be/en/heritage/royal-greenhouses-in-laeken

Kew did not have the money to buy her plants, instead some ended up in the greenhouses of the King of the Belgians at Laeken whilst most were sold to the “Administration of Monte Carlo… and many of them found a home in the pretty gardens surrounding the great Temple of Chance.”

What remained she took in 3 vans to her new home, Stillyans near Heathfield in East Sussex which she rented from one of her botanical friends Dr Robert Hogg, editor of the Journal of Horticulture.

At Stillyans she started on a new garden, much smaller in scale and much wilder and less formal in approach to keep down the maintenance costs, but which became impressive in its own way. She found fresh scope for her energies there in breeding black sheep, as well as crayfish, storks and Cornish choughs. “I am not philanthropic,” she once said in a cynical mood, “and prefer animals to my own species.” However by 1894 she could no longer afford this house either and gave it up, spending most of her time in London and renting the much smaller Tudor Cottage outside Haslemere in Surrey so she could visit her son who was a clergyman nearby.

Dorothy Nevill wrote several books towards the end of her life, including one on Walpole family history and another on silkworms. These were followed by three volumes of autobiography. The Reminiscences of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1906), Leaves from the Notebooks of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1907), and Under Five Reigns (1910). All available at archive.org. She finally died aged 85 on 24 March 1913 at her home at 45 Charles Street, London.

Sunken Terrace Gardens from the 1926 Sale Particulars PGDS 1932

Dangstein was bought by Charles Lane, a London solicitor, who must have dismayed Lady Dorothy by dismantling many of the glasshouses. It was sold again by his widow in 1919, and then again in 1926 this time to Walter Quennell a London property developer. Quennell demolished the mansion, which by this time was partly derelict, and built a more modest and comfortable replacement. The estate was inherited by his daughter, Joan Quennell who was Tory MP for Petersfield, and she in turn bequeathed it to the National Trust. The Trust felt the estate did not have sufficient historical interest to be opened to the public and, despite considerable local concern sold it in 2007. As far as I can discover, some of the outlying properties were sold off but the main part of the estate remains intact.

For more information see R. Nevill, The life & letters of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1919) · G. Nevill, Exotic groves: a portrait of Lady Dorothy Nevill (1984) · W. R. Trotter, ‘The glasshouses at Dangstein and their contents’, Garden History, 16/1 (1988), 71–89:

and of course the entry on our database: http://www.parksandgardens.org/places-and-people/site/5205/summary

The Gates to the Parterre, 2007. Sussex Gardens Trust

George Kruger Gray (25 December 1880 – 2 May 1943) was an English artist, best remembered for his designs of coinage and stained glass windows.

Personal life

Kruger was born in 1880 at 126 Kensington Park Road, London, the son of a Jersey merchant, and was christened George Edward Kruger in Kensington.

He received his tertiary education at the Bath School of Art (today Bath School of Art and Design a department of Bath Spa University). There he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in London, from which he graduated with a Diploma in Design in his birth name George Edward Kruger. From 1905 he exhibited water colours at the Royal Academy, specialising in landscapes, flower studies and portraits.

During the First World War, Kruger served with the Artists Rifles, and a camouflage unit of the Royal Engineers which specialised in hiding military items and making dummy objects to confuse enemy forces.

In 1918, following his marriage to (Frances) Audrey Gordon Gray, he changed his name to George Kruger Gray.

After the war, he continued his career as an artist. In 1923, he exhibited his numismatic works at the Royal Academy of Arts, winning a considerable reputation in that area, and receiving orders to design coins for Great Britain, as well as other parts of the Empire.

In 1938, he became a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE)

Although best known for the design of numismatic items, he also designed and made stained glass windows for churches, universities and the like. As well, he illustrated books, and made posters and cartoons.

Kruger Gray died in Chichester, West Sussex, on 2 May 1943. He is buried in St Mary Churchyard, Fittleworth, Chichester.

Coinage

- Kruger Gray designed the Reverse ("Tails") of most of Australia's second set of currency, used from 1937 until the changeover to decimal currency in 1966. This included the halfpenny, penny, threepence, shilling, florin and crown. (The sixpence did not change design.) Additionally, he designed the reverses of the commemorative florins for 1927 and 1935.

- In Canada, he designed the reverse of the one cent (penny) in use from 1937-2012, five cents (nickel) in use from 1937 to the present day, and 50-cent coins in use from 1937 to 1958.

- For Cyprus, he designed the reverse of the 1938–1940 9 piastres and 18 piastres, 1928 45 and 4½ piastres, and 1947–1949 florin.

- For Great Britain he designed the reverse for the 1927–1945 silver threepence, 1927–1948 sixpence, 1927–1936 shilling, both the Scottish and English motifs for the 1937–1948 shilling, 1927–1948 florin, 1927–1948 half crown, 1927–1936 crown (except for the 1935 Jubilee crown), and 1937 crown. The 1927 date was issued on as proof specimens. His designs for the shilling (both designs), florin and half crown were continued from 1949-1952, though do not bear his initials 'KG' because the inscription had been modified by the omission of 'IND:IMP' and the layout was therefore modified by another hand.

- For Jersey, he designed the reverse for the 1927–1952 1/12th shilling (the penny) and the 1/24th shilling (the halfpenny).

- For Mauritius, he designed the reverse for the 1 cent, 2 cents, 5 cents and 10 cents for 1937 to 1978, and the 1/4, 1/2 and 1 rupee of 1934–1978, though some of his designs are still being used in the 21st century.

- For New Guinea, he designed the reverse for the 1936–1944 penny, threepence, sixpence and shilling.

- For New Zealand, he designed the reverse for the threepence (depicting crossed patu), the sixpence (depicting a huia bird), the shilling (depicting a Maori warrior holding a Taiaha), the florin (depicting a kiwi), and the half crown reverse 1933–1965.

- For South Africa, he designed the reverse for the ¼d (farthing), ½d (halfpenny), 1d (penny), threepence, sixpence, shilling, florin, and half crown 1923–1960. Reverse 1961–1964 half, two and half, five, ten and twenty cents.

- For Southern Rhodesia, he designed the reverse side of the 1932–1952 threepence, the 1932–1952 sixpence, the 1932–1952 shilling, the 1932–1954 two shillings, and the 1932–1952 half crown.

Other works

Kruger Gray was a well known artisan of his time, and produced a number of coats of arms, including the version used by The University of Western Australia from 1929 to 1963.He also designed the Flag of the Colony of Aden.

He also designed what became an important distinction given to the Royal Naval Patrol Service in the form of an exclusive silver badge. Officers and men of the Patrol Service were awarded this badge after a total of six months service at sea. It could also be awarded beforehand to those showing worthy conduct while engaged in action.

Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, 1939 wrote in the following minute:

FIRST LORD to FORTH SEA LORD I am told that the Minesweepers men have no badge. If this is so it must be remedied at once. I am asking Mr. Bracken to call for designs from Sir Kenneth Clark within one week, after which production must begin with the greatest speed, and distribution as the deliveries come to hand.

The design of the badge measured roughly the size of an old shilling. The design had to symbolise the work of both the minesweeping and the anti-submarine personnel. The finished design took the form of a shield upon which a sinking shark, speared by a marline spike, was set against a background made up of a fishing net with two trapped enemy mines. This was flanked by two examples of the nautical knot and at the top the naval crown. Beneath the badge was a scroll bearing the letters M/S-A/S (Minesweeping Anti-Submarine).

The shark symbolised a U-boat and the marline spike the tool of the Merchant navy. The net and the mines were both symbols of the fishermen who now found themselves at war seeking a new deadly catch. Never before had one section of the Royal Navy been similarly honoured.

His design for an insignia to denote the award of a "King's Commendation for Brave Conduct" was accepted and used for a period from 1943.