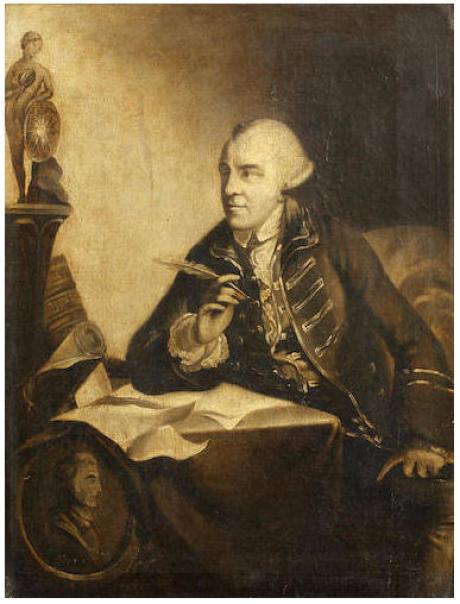

full-length, three-quarters facing left, seated, writing, with a medallion portrait of John Hampden at the lower left and Truth on a pedestal holding a magnifying glass

There is a larger portrait of John Wilkes by Robert Edge Pine in the collection of the Palace of Westminster, Parlimentary art collection painted in 1768 . This portrait has a number of differences in the pose of the hand and is likely to be a studio version of the portrait in Westminster.

Wilkes, John (1725–1797), politician, was born in St John's Square, Clerkenwell, London, on 17 October 1725, the second son of the six children of the malt distiller Israel Wilkes (1698–1761) of Clerkenwell and his wife, Sarah (1700–1781), the daughter of John Heaton, a tanner from Bermondsey. This plebeian though prosperous background was not a promising one for a man with social and political pretensions, but the Wilkes family evidently marked out the clever and charming John for such advancement, and there never seems to have been any suggestion that he should manage the distillery. That task fell to his younger brother Heaton after the eldest son, Israel, had declined it. Having been sent to a school in Hertford in 1734, Wilkes had mastered Latin and Greek by the age of fourteen, and remained a scholar throughout his life. His Presbyterian mother was the dominant figure in the household, but John took the opportunity to break free of moral restraint when he went to the University of Leiden in 1744; he later boasted to James Boswell of his incessant whoring and drinking there. This Dutch interlude ended when he was summoned back for an arranged marriage on 23 May 1747 to a bride some ten years older than himself, Mary Mead (d. 1784), whose dowry from her wealthy widowed mother was the manor of Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire. While it was evidently intended by his parents to establish his fortune, this betrothal was a mismatch between a simple, devout woman and a sophisticated rake, one that not even the birth of a daughter, Mary (known as Polly), in 1750 could save. For some years Wilkes played a dual role of country squire—he served as a local magistrate in Aylesbury—and London man about town (he was elected to two prestigious clubs, the Royal Society in 1749 and the Beefsteak Club in 1754). Wit and generosity gave him the entry into society his parents had sought for him.

In Buckinghamshire, Wilkes joined the Franciscans or ‘monks of St Francis’ at Medmenham, and doubtless regaled members with the ‘Essay on woman’, an unpublished obscene parody of Alexander Pope's Essay on Man which he wrote in 1754. His evil genius was Thomas Potter, who not only strengthened Wilkes's addiction to vice but also introduced him into politics. Before the parliamentary general election of 1754 Potter deceptively flattered him with the idea of a joint candidature for the two seats at Aylesbury, where Wilkes had an important interest—only for Wilkes to find himself being palmed off with the honorific sop of being county sheriff while Potter was elected with another candidate. The prime minister, the duke of Newcastle, noting his interest in politics, sent Wilkes to fight, at his own expense, the distant borough of Berwick upon Tweed, a hopeless and costly quest. Such political adventures incurred almost as much disapproval by his thrifty and puritanical wife as his fashionable lifestyle, and the marriage broke up. A trial separation in 1756 became permanent the next year, when Wilkes retained the Aylesbury estate and agreed to pay his wife £200 a year. Their daughter chose to live with her father, and their loving relationship was thought even by his severest critics to be a redeeming feature of Wilkes's life.

Wilkes now decided to exploit his electoral influence at Aylesbury, and the opportunity came in 1757, when Potter moved to another seat on being given office by a new ministry headed by the elder William Pitt. Wilkes already knew Pitt as the brother-in-law of his Buckinghamshire neighbours Lord Temple and George Grenville, and enrolled under his banner after an unopposed by-election. Pitt in reply congratulated him ‘on your being placed in a public situation of displaying more generally to the world those great and shining talents which your friends have the pleasure to be so well acquainted with’ (John Wilkes MSS, BL, Add. MS 30877, fol. 5). But Wilkes, so sparkling a companion, was not a fluent public speaker and remained anonymous and silent in parliament. This failure to live up to expectations doomed his various patronage requests to be a lord of trade, ambassador to Constantinople, and governor of Quebec. At the next general election, in 1761, he avoided a contest for his Aylesbury seat by crude bribery, offering 300 of the 500 voters £5 each. Before the new parliament met Pitt resigned office over the cabinet's refusal to back his demand for a Spanish war. Wilkes took Pitt's side, and made his maiden speech supporting him on 13 November 1761, being deemed a follower of Lord Temple. He spoke several more times that session, but soon realized that he would not make his mark in debate. Horace Walpole was disparaging about his performance: ‘His appearance as an orator had by no means conspired to make him more noticed. He spoke coldly and insipidly, though with impertinence; his manner was poor, and his countenance horrid’ (Walpole, Memoirs, 1.142).

The political talent of Wilkes lay in his pen. After an anonymous pamphlet of 9 March 1762, Observations on the Spanish Papers, and some essays in The Monitor, he made his name by his political weekly the North Briton, founded on 5 June 1762 to attack the new ministry of George III's Scottish favourite, Lord Bute. The very name was chosen to adopt a satirical guise of Scottish approval of Bute's take-over of England. Wilkes was personally responsible for most of the text, though the poet Charles Churchill was also an important contributor. The paper, which soon achieved a circulation of nearly 2000, escaped prosecution by shrewd political calculation and legal advice: but individuals offended included Lord Talbot, lord steward of the royal household, who fought a pistol duel with Wilkes on 6 October 1762, and the cartoonist William Hogarth, who was to exact revenge in 1763 by his savage caricature John Wilkes Esquire. This portrayal of an impudent demagogue with a hideous squint was to be the visual image of Wilkes conveyed both to contemporaries and to posterity. More conventional portraits show that he was not quite that ugly, but he himself was famously wont to say that it took him half an hour to talk his face away.

During the Bute ministry (1762–3) the main focus of opposition attack was the treaty of Paris ending the Seven Years' War, condemned as far too generous to defeated France. The North Briton commented on 1 January 1763 that the treaty had ‘saved England from the certain ruin of success’, and the paper constantly reminded readers of the old Scottish alliance with France against England. The journalistic talent of Wilkes soon came to appear the sole recourse of Bute's enemies as opposition in parliament faded early in 1763. Ministerial attempts to silence the paper were unavailing, for government lawyers could find no ground for prosecution.

When Bute resigned on 8 April 1763 he was succeeded as prime minister by George Grenville, who had broken with Pitt and Temple in 1761. Wilkes momentarily held his fire, but when Grenville ended the parliamentary session by a king's speech commending the peace, North Briton no. 45 on 23 April denounced the ‘ministerial effrontery’ of obliging George III ‘to give the sanction of his sacred name’ to such ‘odious’ measures and ‘unjustifiable’ declarations. Immediate prosecution of the paper for seditious libel ensued. But the Grenville ministry made a legal blunder by arresting Wilkes and his associates under a general warrant directed against ‘the authors, printers and publishers’ without naming any persons. The story initially became confused when Wilkes himself was released on the ground of parliamentary privilege. When the crowd in Westminster Hall, ignorant of legal niceties, saw their hero being freed on 6 May, the building echoed with shouts of ‘Wilkes and liberty’. Wilkite mobs on London streets became a common phenomenon during the next dozen years. Wilkes now challenged the legality of the general warrant by actions for damages and false arrest. There already existed doubts on that point; but an expensive and sustained legal challenge was now made possible by the deep purse of Lord Temple, ironically the prime minister's eldest brother.

The ministerial campaign against Wilkes preceded legal decisions on general warrants. Wilkes had unwisely given a hostage to fortune by privately printing off a few copies of the Essay on Woman. The ministry obtained a copy, and further blackened his already unsavoury reputation by having it read out to a crowded House of Lords when parliament met on 15 November 1763. The House of Commons resolved on the same day that the North Briton was a seditious libel, and on 24 November that parliamentary privilege did not cover seditious libel, thereby exposing Wilkes to punitive legal action. The Commons debate of 15 November, moreover, had resulted in a pistol duel the following day in Hyde Park between Wilkes and an MP, Samuel Martin, who had impugned his personal courage. Wilkes was so badly wounded in what many thought a plot against his life that he was unable to attend any further legal or parliamentary proceedings. Before the end of the year he had fled from justice: he crossed to France on 25 December and took up residence in Paris. Pleading ill health, he refused to attend either parliament or the law courts.

The House of Commons on 19 January 1764 received evidence that Wilkes had published the North Briton, and so expelled him as unworthy to be a member, without a vote. Politicians concerned about the issues he had raised were not willing to defend the man himself. But the legality of general warrants was a matter of widespread concern, and after a run of acrimonious debates the ministry avoided a parliamentary defeat on 17 February by only fourteen votes, 232 to 218. The trial of Wilkes for libel followed four days later in the court of king's bench. He was convicted of publishing the North Briton and the Essay on Woman, but no attempt was made to prove his authorship. After he had failed to answer five summonses to attend, he was outlawed on 1 November. The North Briton case nevertheless produced a victory for ‘liberty’ in the total condemnation of general warrants. Already on 6 December 1763 Chief Justice Charles Pratt had ruled in the court of common pleas that general warrants could not be used as search warrants of unspecified buildings. This verdict was complemented by judgments of Chief Justice Lord Mansfield in the court of king's bench on 18 June 1764 and 8 November 1765 that ended the use of general warrants for the arrest of persons.

Wilkes was to remain abroad for four years, since his return to Britain would have meant imprisonment. Later he recalled, admittedly to a Paris correspondent, that he was ‘never so happy’ as in his French exile (Wilkes MSS, U. Mich., Clements L., III, no. 26). He entered the dazzling intellectual society of Paris through the salon of Baron D'Holbach, a former fellow student at Leiden, and was lionized as a champion of liberty. He acquired a tempestuous Italian mistress in the nineteen-year-old dancer Gertrude Corradini, but on a journey to Italy in 1765 she decamped with all she could carry. Wilkes stayed for four months in Naples, and then made his way to Geneva, spending two months in the company of Voltaire. He returned to Paris in the hope of help from the first Rockingham ministry, former opponents of Grenville, for his affairs were now desperate. Afraid of the financial consequences of debt and outlawry, he had liquidated his assets in Britain: the manor of Aylesbury was sold for £4000, his library for £500. But the friend, Humphrey Cotes, to whom he had entrusted the management of his finances, proved neither competent nor honest. After Wilkes received £1000 in the first half of 1764, he obtained not a penny more from Cotes. Numerous requests to the Rockingham ministry for a pardon and patronage, backed by a mixture of flattery and threats, produced only a precarious income of £1000, voluntarily subscribed by friends in that administration. Wilkes unofficially visited Britain in May 1766 in a vain attempt to extort a pardon, and did so again in the autumn after the duke of Grafton took over the Treasury on behalf of Lord Chatham, the former Pitt. Grafton declined to help him, and a furious Wilkes returned to France to write a scathing pamphlet, Letter to the Duke of Grafton, an attack on ‘flinty heart’ Chatham, that served to bring Wilkes back to public attention and to pave the way for his return to Britain. News of the bankruptcy of Cotes in the summer of 1767 may have been the final spur, if credence may be attached to this apocryphal statement: ‘What the devil have I to do with prudence? I owe money in France, am an outlaw in England … I must raise a dust or starve in a gaol’ (Bleackley, 185). Wilkes intended to obtain a parliamentary seat at the general election due by March 1768, and to do so through popular election, not by purchase or gift from an admirer. He visited London briefly in December 1767, and returned in February 1768, living quietly under the name of Osborn until parliament was dissolved on 11 March. No answer was made to a request for pardon that he submitted to the king on 4 March, but neither was there any attempt to apprehend him. Wilkes, to resolve this anomalous situation, formally announced his intention to surrender himself to justice when the court of king's bench next met, on 20 April, and meanwhile busied himself with securing a parliamentary seat.

Wilkes defied the advice of his friends and stood for the City of London in the election on 25 March 1768, but he came last of seven candidates for the four seats, with a mere 1247 votes, as against 2957 for the lowest successful candidate. He blamed his failure on the shortness of his campaign, and dropped a bombshell by promptly announcing that he would challenge the two sitting members for the county of Middlesex (in effect Greater London with a rural surround). A clockwork campaign organized both propaganda and transport to the county town of Brentford, 10 miles from the City. Superb organization was reinforced by popular enthusiasm, as crowds intimidated supporters of his two opponents, the Chathamite George Cooke and the independent Sir William Proctor. In a low poll on 28 March, Wilkes triumphed by 1292 votes to 827 for Cooke and 807 for the defeated Proctor.

The cabinet, headed by the duke of Grafton, promptly decided to expel Wilkes from parliament on the assumption that he would be imprisoned after his court appearance on 20 April. But Lord Mansfield deemed his attendance in court voluntary, and the ministry feared a riot if he was arrested. Wilkes, anxious to resolve the legal situation, delivered himself into custody on 27 April, only to be freed by a mob. In a farcical sequel to this episode he stole into prison in disguise, giving rise to obvious jokes. On 8 June his outlawry was revoked on a technicality, but six days later he was sentenced for his 1764 convictions, a year each for publishing the North Briton and the Essay on Woman. The whole Middlesex election case was played out while he remained in king's bench prison.

That famous saga was preceded by a by-election caused by Cooke's death. John Glynn, Wilkes's leading counsel, defeated Proctor in a poll in December 1768 by 1542 votes to 1278, a result that signified the Wilkite hold on Middlesex more obviously than the snap victory of Wilkes himself. A petition from Wilkes about his treatment in 1764, and a newspaper piece by him on 10 December, accusing the ministry of having deliberately planned a military attack on a Wilkite crowd outside his prison on 10 May that resulted in several fatalities, provoked the wavering Grafton cabinet into a renewed determination to expel him from parliament. This was achieved on 3 February 1769 by a composite resolution listing five libels, two as seditious and three as obscene, the former being the newspaper item of 10 December 1768 and the North Briton, and the latter drawn from the Essay on Woman. Many deemed this mode of proceeding unfair, but the expulsion was carried by 219 votes to 137. Wilkes was not the man to accept such treatment, and he was returned unopposed at a by-election on 16 February 1769. Next day the House of Commons resolved Wilkes to be ‘incapable’ of election, since he had been expelled, and later again voided his return in a second by-election on 16 March. To end this monthly ritual, the ministry, for the third by-election on 13 April, produced a rival candidate, Colonel Henry Luttrell, who was well protected by soldiers. Although Wilkes defeated Luttrell by 1143 votes to 296, the latter was awarded the seat by the Commons two days later. The episode became a major political controversy, as the parliamentary opposition challenged the decision both at Westminster, where the ministerial majority fell to 54 over the seating of Luttrell, and in a summer petitioning campaign throughout England. The topic dominated the opening of the new parliamentary session in January 1770, and Grafton resigned as prime minister when his Commons majority fell to forty; however, Lord North stepped into the breach, to become prime minister for the next twelve years. Wilkes had felled one prime minister, but had not brought down the king's government.

Wilkes had no intention of being the cat's-paw of the parliamentary opposition. Deprived of a Commons seat until the next general election, he intended to make London his power base, for the democratic structure of City government was open to exploitation by such a popular hero. The 7000 liverymen annually chose the City officials and the court of common council, and also, within each of the twenty-six wards, the aldermen for life as vacancies arose. But before the political career of Wilkes could be relaunched, his finances had to be put in order, if his release from the king's bench prison in April 1770 was not to be followed by immediate imprisonment for his debts, estimated at £14,000 in February 1769. That month the Society of Gentleman Supporters of the Bill of Rights was formed, and made the settlement of these debts its first task, a herculean one in the face of Wilkes's continued extravagance even in prison. Already Wilkes himself had secured election as alderman, for the ward of Farringdon Without in January 1769, and that year saw Wilkites procure City offices and become aldermen. But a split among Wilkites resulted from the intention of a group led by John Horne to make the Bill of Rights Society a truly radical organization and not merely a vehicle for the payment of Wilkes's debts. An escalating quarrel led on 9 April 1771 to secession by Horne and his supporters, who formed a new Constitutional Society. However, despite this quarrel, both factions co-operated in the simultaneous contest with the House of Commons over parliamentary reporting.

Hitherto parliamentary reporting had been suppressed by direct action by both houses against newspapers and magazines. The successful challenge to this censorship in 1771 followed a tactical coup masterminded by Wilkes. The political excitement generated by the Middlesex election had led to a significant expansion of the London press, and by early 1771 this had resulted in extensive reporting of parliamentary debates. The attempt by the Commons to stop this practice was initiated by two ministerial supporters, and the North administration soon gave it official backing. On 7 February 1771 two printers were summoned to appear, and on 26 February their non-attendance led to orders for their arrest. Wilkes, realizing that the campaign would be extended to other newspapers, devised a plan to thwart this policy. He would pit against the power of parliament the privilege of the Wilkite-dominated City of London, which claimed an exclusive right of arrest within its own boundaries, and where printers would be encouraged to take refuge. The beauty of the scheme was that secrecy was not necessary. Once the House of Commons had embarked on its course of action, confrontation would be inevitable. And so it proved. Six more printers were added to the list on 12 March, and three days later an attempt to arrest one of them in the City, John Miller of the London Evening-Post, a Wilkite newspaper, was frustrated by City magistrates. It was in vain that the Commons imprisoned the Wilkite Lord Mayor Brass Crosby and another alderman. Wilkes himself, the third official directly concerned, refused to obey the summons before the house, and the Commons chose not to pursue the matter; Chatham was informed on 24 March that ‘the ministers avow Wilkes too dangerous to meddle with. So his Majesty orders: he will have “nothing more to do with that devil Wilkes”’ (Correspondence of William Pitt, 4.122–3). In London even ministerial supporters deemed it prudent to support the City's privilege, and parliamentary reporting continued from within this safe haven. The North ministry tacitly conceded defeat, and thenceforth newspaper reporting of parliament was established. The administration had been outmanoeuvred by the astute Wilkes, even though the parliamentary opposition had shunned the project. Once the fatal step into the City had been taken the government was unable to extricate itself from the trap. There was a sequel to this episode in 1775 when Wilkes, then lord mayor, threw down the same gauntlet to the House of Lords, which declined a confrontation, for the consequences of committing him to the Tower were too horrendous to contemplate. This freedom of the press to report parliament was a significant long-term gain for ‘liberty’ in ensuring responsibility of MPs to their constituents.

This so-called Printers' case was the greatest triumph of Wilkes arising from his power within the City of London, but during the next few years he further exploited the political situation there to embarrass government. It was a three-sided contest, for the secession group led by John Horne competed with the Wilkites in radical zeal and for City posts, while the North ministry sought to exploit the split among its opponents. Wilkes did not himself draft the political programme put forward by the Bill of Rights Society on 23 July 1771, but he endorsed it and personally advocated annual parliamentary elections and the abolition of pocket boroughs. In the 1771 election of City sheriffs he and his acolyte Frederick Bull defeated two ministerial candidates. As sheriff, Wilkes adopted a high profile, out of a genuine concern for ‘liberty’ as well as to cultivate his public image. He sought to prevent government ‘packing’ of juries, and criticized the multiplicity of death sentences for trivial crimes. This role was a preliminary to the 1772 election of lord mayor. Wilkes duly headed the poll, but the court of aldermen exercised its right to choose the second candidate, the Hornite James Townsend. ‘Wilkes was thunderstruck, and, for once, angry in earnest’, noted Horace Walpole (Last Journals of Horace Walpole, 1.158). A year later the ministry stood aside as Wilkites fought Hornites. Wilkes and Bull came first and second, only for an alliance of ministerialists and Hornites in the court of aldermen to choose Bull, a treatment of Wilkes that proved counter-productive, as Walpole commented: ‘This proscription of Wilkes, though for two years together he was first in the poll, did but serve to revive his popularity from the injustice done him’ (ibid., 1.250).

For most of 1774 the inevitable candidature of Wilkes for lord mayor dominated London politics. The situation was complicated by the ministerial decision to call a general election in the autumn of 1774, but Wilkes gained by a bargain with John Sawbridge, hitherto a leading Hornite. Sawbridge was promised Wilkite support for a London parliamentary seat, and in return prevented radical opposition at the mayoral elections to Wilkes and Bull, who defeated two ministerial candidates. This time the court of aldermen accepted Wilkes, again top of the poll. Soon afterwards Wilkes re-entered the Commons, being returned unopposed with Glynn for Middlesex, to the vain fury of king and ministers.

The mayoralty of Wilkes was one of the most splendid in London's history. His generosity, popularity, and flair for publicity combined to make it memorable; and affection for his daughter, Polly, an elegant lady mayoress, also explained why he put on such a show. He gave frequent and lavish entertainments—his expenses of £8226 exceeding by £3337 his official allowances—and he ended heavily in debt. Wilkes, as when sheriff, took his duties seriously. He concerned himself with the regulation of food prices and with charity for prisoners, and he initiated a campaign against prostitutes, thereby gaining respect and respectability; the archbishop of Canterbury attended one of his functions. Genial host and busy administrator, Wilkes hoped to take advantage of his popularity by securing election to the lucrative if onerous post of City chamberlain, manager of London's finances. But, after persuading the incumbent to resign, he was defeated in 1776 by a ministerial candidate, for by then his seemingly unpatriotic opposition to the American War of Independence was proving to be a solvent of Wilkite control of the City.

Contrary to legend, Wilkes never championed the cause of American independence in principle. Nor was he even always sympathetic to colonial grievances. His reaction, when in France, to news of the Stamp Act crisis in 1765 was to comment to his brother Heaton that ‘there is a spirit little short of rebellion in several of the colonies’ (Wilkes MSS, U. Mich., Clements L., I, no. 91). But during the next few years colonial adulation of Wilkes as a hero of liberty led him to adopt the idea of a common cause on both sides of the Atlantic. He offered words of encouragement to America, commending resistance to the 1767 import duties on tea and other items, and deploring the use of soldiers in Boston, by an analogy with events in London. After the Boston Tea Party of 1773 had reignited the American question, the colonial cause afforded new ground on which to attack government as the Middlesex election lost its appeal. Wilkes took little part in London agitation against ministerial policy in 1774, but once he was lord mayor he busied himself in organizing a series of City petitions. When he presented a remonstrance to George III on 10 April 1775 his conduct was such that it was said ‘the King himself owned he had never seen so well-bred a Lord Mayor’ (Last Journals of Horace Walpole, 1.456). But George III then foiled this propaganda tactic of Wilkes by vetoing any repetition of such ceremonies. As the colonial crisis escalated Wilkes shifted his ground from merely supporting American resistance to taxation, as in a Commons speech of 6 February 1775, to endorsement of the colonial denial of parliament's authority, as on 26 October; but the final demand for independence he did not accept. In parliament, urging conciliation rather than coercion, he therefore denounced the American war only as bloody, expensive, and, above all, futile, telling the Commons on 20 November 1777 that ‘men are not converted, Sir, by the force of the bayonet at the breast’ (Almon, 8.8). After news of Burgoyne's surrender at Saratoga, Wilkes on 10 December 1777 moved repeal of the Declaratory Act of 1766 as a final attempt to save the colonial link, but secured only ten votes. The failure of the 1778 peace commission led him to urge recognition of American independence, in a speech of 26 November 1778: ‘A series of four years disgraces and defeats are surely sufficient to convince us of the absolute impossibility of conquering America by force, and I fear the gentle means of persuasion have equally failed’ (Almon, 11.21). That he believed American independence to be inevitable was misinterpreted then, and later, as support for the idea: the case was rather that his realism anticipated majority British opinion by several years. But the outbreak of the American war had proved the kiss of death to City radicalism. Deprived of that power base, Wilkes became more active in Westminster politics.

The parliamentary behaviour of Wilkes on his return to the Commons in 1774 confounded all expectations. He did not create his own radical party, as he lacked the reputation and resources to do so—and indeed sufficient supporters, once dubbing them his ‘twelve apostles’. Nor did he enlist in either of the opposition parties led by lords Rockingham and Shelburne. But he was not the silent back-bencher many expected from his earlier spell in the house. He spoke regularly in debate, delivering prepared speeches, marked by detailed research and literary polish, that, though designed for the press rather than parliament, fully merited the attention his character and reputation secured for them. The diarist Nathaniel Wraxall recalled that he was an incomparable comedian in all he said or did; and he seemed to consider human life itself as a mere comedy … His speeches were full of wit, pleasantry, and point; Yet nervous, spirited, and not at all defective in argument. (Wraxall, 2.296–7) Every session Wilkes moved to rescind the resolution of 17 February 1769 declaring him incapable of election after expulsion. On the first occasion, 22 February 1775, the North ministry was pushed harder than on America, winning only by sixty-eight votes, but thereafter the motion became one of form until the resignation of North in 1782. That Wilkes made the first ever motion for parliamentary reform, on 21 March 1776, established his radical credentials for posterity. He urged the transfer of seats from rotten boroughs to London, the more populous counties, and the new industrial towns. The motion was defeated without a vote, and afterwards, in the 1780s, Wilkes, while remaining a reformer, allowed others to take the lead.

‘Liberty’ for Wilkes embraced wider objectives than political aims. Although brought up a dissenter, from the 1750s he was a professed Anglican, but he held extremely liberal views on religious toleration, expounding them when supporting a Dissenters Relief Bill on 20 April 1779. After pointing out that a person's religion was due to accidents of time and place of birth, Wilkes declared:

I wish to see rising in the neighbourhood of a Christian cathedral … The Turkish mosque, the Chinese pagoda, and the Jewish synagogue, with a temple of the Sun. … The sole business of the magistrates is to take care that they did not persecute one another. (Almon, 12.311)

Wilkes was a conspicuous absentee when fellow radicals organized City protests against the Quebec Act of 1774 for establishing the Catholic church in Canada, and he had scant sympathy with the anti-Catholic Gordon riots in London during June 1780. He took an active role in their suppression, receiving accolades from supporters of government but incurring unpopularity in London. It signified his final transformation into respectability, one underpinned at last by financial security. The City chamberlain who had defeated him in 1776 died on 9 November 1779, and Wilkes routed a ministerial candidate by 2343 votes to 371, formally taking office on 1 December 1779.

When Lord Rockingham succeeded North as prime minister in 1782 Wilkes was at last able, on 3 May, to carry his motion to erase the 1769 resolution on the Middlesex election, thereby belatedly establishing the right of voters to choose any eligible candidate. But soon there occurred a seismic change in his political career. After Rockingham's death on 1 July 1782, Charles James Fox led the bulk of his party back to opposition when George III chose Shelburne as the new prime minister. Wilkes disliked Fox's attempt to bully the king and chose to support Shelburne, demonstrating that his frequent professions of loyalty to the crown had not been mere formality. He therefore opposed the Fox–North coalition of 1783, denouncing their East India Bill in a much-admired speech as confiscation paving the way for corruption, and became a follower of the younger Pitt, not least because he was a parliamentary reformer. At the general election of 1784 he fought Middlesex as a ministerial candidate and scraped home by sixty-six votes. Thenceforth he was an occasional and silent Pitt supporter, and made only one more recorded speech, seeking in 1787 to prevent the impeachment of his friend Warren Hastings. But unpopularity for both his support of government and his neglect of parliamentary duties cost him his seat without a contest at the 1790 general election. His political career ended in irony. He detested the violence and political extremism of the French Revolution; but on 11 June 1794 a loyalist mob, perhaps from folk memory, smashed the windows of his house. Wilkes refused to prosecute, saying, ‘they are only some of my pupils, now set up for themselves’ (Morning Post, 24 June 1794).

‘Mr. Wilkes was the pleasantest companion, the politest gentleman, and the best scholar he knew’ (John Wilkes MSS, BL, Add. MS 30874, fol. 92). This 1783 tribute from Wilkes's old adversary Lord Mansfield serves as a reminder that politics never filled his life. Pursuit of women engrossed much of his attention; he was a man of culture; and from 1779 he had duties as City chamberlain. All this activity took place against a background of financial difficulty, eased but not solved by his chamberlain's income, which fluctuated between £1500 and £3000, and at least ended his earlier dependence on private donations. He always spent freely, without heed for the morrow, was often pressed for money, and died virtually insolvent.

The post of City chamberlain was no sinecure. Wilkes supervised a staff of seven, to administer official and charitable funds, and had various other duties, such as the admission of freemen. He worked hard, visiting the Guildhall several days a week to the end of his life, and contemporaries attested to his efficiency. His zeal as an administrator, already displayed as a Buckinghamshire magistrate, London alderman, City sheriff, and lord mayor, was a facet of his character often overshadowed by his political and social activities.

So also was the cultural thread of his life. Wilkes amassed a personal library of altogether nearly 3000 books and pamphlets. He read and wrote in French, and knew both Latin and Greek. His correspondence and speeches alike were laced with classical and other literary allusions. In a debate of 28 April 1777 on the British Museum he made a far-sighted plea for the establishment of a copyright national library and national art gallery. During the last decade of his life he gave fuller vent to his literary turn of mind, publishing editions of Catullus in 1788 and Theophrastus in 1790, respectively in Latin and Greek.

But the wider contemporary world knew Wilkes only as a profligate. That he loved all women except his wife was his famous boast. His overt sexual promiscuity, which was emphasized by bawdy language and lack of shame, began before his arranged marriage, from which there could be no escape of divorce and which he gave as an excuse for his conduct to his daughter when he assured her, ‘I have since often sacrificed to beauty, but I never gave my heart except to you’ (John Wilkes MSS, BL, Add. MS 30880B, fol. 71). He did not remain faithful even to his current mistresses, of whom the most enduring was Amelia Arnold (b. 1753). He set her up in a nearby house for the last two decades of his life, and she was mother of an acknowledged daughter, Harriet Wilkes, born in 1778. An earlier illegitimate child, born in 1760 to his housekeeper, was passed off as his nephew John Smith, a papal nephew joked Wilkes, who in 1782 obtained for him a post in India.

Somehow Wilkes contrived to fit in a conventional social life among all these interests. He did not hunt or gamble, and indeed boasted that he had ‘no small vices’. Instead he simply enjoyed company. His engagement diary records numerous occasions when he was either at private houses or at public dinners. Wraxall recalled how ‘in private society, particularly at table, he was pre-eminently agreeable, abounding in anecdote, ever gay and convivial … He formed the charm of the assembly’ (Wraxall, 2.297). Wilkes, a tall and thin man, enjoyed good health, and preferred to walk the 3 miles from his Westminster home to Guildhall rather than hire a carriage. Towards the end of his life he became emaciated, and the reputed cause of his death on 26 December 1797, at his house, 30 Grosvenor Square, Westminster, was marasmus, a disease of malnutrition. He was buried in Grosvenor Chapel, South Audley Street, Westminster, on 4 January 1798.

Posterity has been reluctant to accept that Wilkes, a womanizer and blasphemer, and a man with a cynical sense of humour, could have possessed genuine political principles, a verdict seemingly confirmed by such stories as his comment to George III that he had never been a Wilkite, and his rebuke to an elderly woman who called out ‘Wilkes and liberty’ on seeing him in the street: ‘Be quiet, you old fool. That's all over long ago’ (Bleackley, 376). Nor did his overnight conversion in 1782 from radical to courtier do his reputation any good, even though he received no reward in honour or office. That last twist to his career is irrelevant to his earlier political record. For two decades Wilkes fought for ‘liberty’, whether freedom from arbitrary arrest, the rights of voters, or the freedom of the press to criticize government and report parliament. He suffered exile, financial ruin, and imprisonment for his principles, and by a combination of political courage and tactical skill won notable victories over government. He thereby earned respect from Lord North. In a debate of 27 November 1775 the prime minister declared that one Wilkes was enough, ‘though, he said, to do him justice, it was not easy to find many such’ (Almon, 3.214–30). After Wilkes British politics would never be the same again: his career permanently widened the political dimension beyond the closed world of Westminster, Whitehall, and Windsor.

Peter D. G. Thomas DNB

Pine, Robert Edge (1730–1788), painter, was born in London, the son of John Pine (1690–1756), an engraver. John Pine's other children were Simon (d. 1772), a miniature painter, Horace (1731–1770), Charlotte, and another daughter whose name is unknown and who married the painter Alexander Cozens. Nothing is known of Robert Edge Pine's early years, although it is presumed he would have received some instruction from his father. On 23 December 1749 he married Mary Fulford at the church of the Holy Sepulchre, Holborn, London. They had four known daughters, Elizabeth, Anne Charlotte, Rose, and a Miss J. He seems to have painted from the beginning the range of subject matter that he continued to use throughout his life: history paintings, theatrical subjects, and portraits. One of his earliest works was Thomas Lowe and Mrs Chambers as Captain Macheath and Polly, engraved in mezzotint by James McArdell in 1752. Pine was active in the Society of Arts and was on the committee of polite arts. In March 1759 he proposed to the society that it hire a room for exhibitions of the works of ‘the present painters and sculptors’ (Paulson, 2.308), one of the moves that led to the foundation of the Society of Artists in 1760.

In 1760 Pine won the first premium for historical painting at the Society of Arts with The Surrender of Calais to Edward the Third which was also exhibited at the first exhibition of the Society of Artists (1760, no. 42). He won the first premium again in 1763 with Canute the Great Reproving his Courtiers for their Impious Flattery (destroyed by fire in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1803), which was exhibited at the Free Society of Artists in the same year (no. 159), and again at the special exhibition of the Society of Artists in 1768 (no. 89). Both pictures were engraved by François Germain Aliamet.

Pine exhibited at the Society of Artists from 1760 to 1771, and at the Free Society of Artists from 1761 to 1763. Among his paintings exhibited in these years were George II (1759; Audley End, Essex), The Earl of Northumberland Laying the Foundation Stone of Middlesex Hospital (1761; Middlesex Hospital, London), and Mrs Yates as Medea (1770). In 1759 John Hamilton Mortimer became his pupil. Both artists through the 1760s were actively involved with the Society of Artists and sat on various of its committees. It is likely that Pine's radical political views were encouraged through the contacts he had made in the Society of Arts, for example with the republican Thomas Hollis, and in certain sections of the Society of Artists. Pine's republican sympathies led him to paint the portraits John Wilkes (1768; Palace of Westminster, London), Richard Oliver (1771; Guildhall Art Gallery, London), and Brass Crosby (1771; Daily Telegraph, London), the subjects of the last two being imprisoned in the Tower of London at the time for supporting the publication of parliamentary debates.

During the 1760s Pine was one of the leading portrait painters in London. On 5 October 1771, after a quarrel with the Society of Artists and probably its president, James Paine, over an unknown ‘insult’ he erased his name from the society, and although the case dragged on his resignation was eventually accepted on 22 June 1772; he never exhibited there again. Pine exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1772, 1780, and 1784. In 1772 his brother Simon died and Pine moved to Bath, where he lived for eight years, for some of this time in close proximity to his nephew, the watercolour painter John Robert Cozens. Pine's address in Bath from at least 1775 to 1779 was at Cross Bath in the parish of St Peter and St Paul.

Pine continued to paint portraits, including one of David Garrick, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1780 (possibly the version now in the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC). His republican views led him to support the cause of American independence and he came to know a number of supporters of America such as George William Fairfax, in Bath, a friend of George Washington, and Samuel Vaughan, a London friend of Benjamin Franklin. In 1778 he painted the allegorical picture America, now only known from an engraving by Joseph Strutt of 1781. He also held an exhibition of his work in the great room at Spring Gardens, London, in 1782, which included a series of Shakespearian scenes, an ambitious work which anticipated John Boydell's Shakspeare Gallery.

Following his political convictions, Pine decided to go to America and was settled in Philadelphia by August 1784. In the same year he wrote, ‘I think I could pass the latter part of my life happier in a Country where the noblest Principles have been defended and establish'd than with the People who have endeavoured to subdue them’ (Stewart, 20). By 27 October 1784 Pine had opened a gallery in the state house, Philadelphia, with paintings he had brought from England. A Descriptive Catalogue of Pictures Painted by Robert Edge Pine, produced by Francis Bailey, a local printer, in the same year, lists America and about ten Shakespearian pictures, including illustrations to Lear, Hamlet, Macbeth, The Tempest, and As You Like It, and also a picture of Boadicea. These paintings were destroyed by fire in Daniel Bowen's Columbian Museum in Boston, in 1803, after Pine's death.

Pine continued to paint portraits in America. With letters of introduction from the writer and composer Francis Hopkinson and the lawyer and writer Thomas McKean he stayed from 28 April to 16 May 1785 at Mount Vernon, where he painted George Washington. He sometimes travelled to the south for portraiture, painting faces on small canvases which were later incorporated into larger ones and completed in his studio. He also painted, with Edward Savage, Congress Voting Independence (Historical Society of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), and three other untraced pictures of the American War of Independence.

According to John Hopkinson, Pine died of apoplexy on 12 November 1788 in Philadelphia. His will, which had been drawn up on 23 August 1782, was filed for probate in Philadelphia on 22 September 1789. His widow, Mary, was the sole beneficiary and executor. John Hopkinson said Pine was ‘a very small man—morbidly irritable’ and added that his wife and daughters were also very small, ‘indeed a family of pigmies’ (Dunlap, 1.377) and, according to Farington, Rose Pine was ‘insane’ (Farington, Diary, 3.778, 25 Feb 1797). Pine's widow received some charity from the Royal Academy in the 1790s (ibid., 2.364, 10 July 1795; 3.1033, 20 July 1798).

John Sunderland DNB