John Philpot Curran (24 July 1750 – 14 October 1817) was an Irish orator, politician, wit, lawyer and judge, who held the office of Master of the Rolls in Ireland. He was renowned for his representation in 1780 of Father Neale, a Catholic priest horsewhipped by the Anglo-Irish Lord, Viscount Doneraile, and in the 1790s for his defence of United Irishmen facing capital charges of sedition and treason. His courtroom speeches were widely admired. Lord Byron was to say of Curran, "I have heard that man speak more poetry than I have seen written". Karl Marx described him as the greatest "people's advocate" of the eighteenth century.

Born in Newmarket, County Cork, he was the eldest of five children of James Curran, seneschal of the Newmarket manor court, and Sarah, née Philpot.

The Curran family were said to have originally been named Curwen, their ancestor having come from Cumberland as a soldier under Cromwell during the Cromwellian Conquest of Ireland and have originally settled in County Londonderry. Curran's grandfather was from Derry, but settled in Cork. The Philpot family occupation were Irish judges, lawyers, bishops, priests and noblemen.

A friend of the family, Rev. Nathaniel Boyse, arranged to have Curran educated at Midleton College, County Cork. Before his entry into Trinity College, he was examined by Rev. Charles Bunworth, who was so impressed by the young Curran that he offered him financial assistance for his studies.[7] He studied law at Trinity College Dublin.[8] (he was described as "the wildest, wittiest, dreamiest student") and continued his legal studies at King's Inns and the Middle Temple. He was called to the Irish Bar in 1775. Upon his first trial, his nerves got the better of him and he couldn't proceed. His short stature, boyish features, shrill voice and a stutter were said to have impacted his career, and earned him the nickname "Stuttering Jack Curran".

However, he could speak passionately in court on subjects close to his heart. He eventually overcame his nerves, and got rid of his speech impediment by constantly reciting Shakespeare and Bolingbroke in front of a mirror, and became a noted orator and wit.

His occasional tendency of challenging people to duels (he fought five in all) rather than compromise his values, along with his skilful oratory, quick wit and his championing of popular Irish causes such as Catholic Emancipation and the enlargement of the franchise, made him one of the most popular lawyers in Ireland. He also could speak Irish, still the language of the majority at that time. He wrote a large amount of humorous and romantic poetry.

The case which cemented Curran's popularity was that of Father Neale and St Leger St Leger, 1st Viscount Doneraile at the County Cork Assizes in 1780. Father Neale, an elderly Catholic priest in County Cork, criticised an adulterous parishioner. The adulterer's sister was mistress to Lord Doneraile, a cruel Protestant landlord. Doneraile demanded that Neale recant his criticism of his mistress' brother. When the priest stood by his principles, Doneraile horse-whipped him, secure in the confidence that a jury of the time would not convict a Protestant on charges brought forward by a Catholic. Curran, who had a passion for lost causes, represented the priest and won over the jury by setting aside the issue of religion. The jury awarded Curran's client 30 guineas. Doneraile challenged Curran to a duel, in which Doneraile fired and missed. Curran declined to fire.

The year 1796 saw Curran again attacking the character of a peer, the Earl of Westmeath, in a civil case. The circumstances were very different from the Doneraile case: Curran was defending another aristocrat, Augustus Bradshaw, allegedly the lover of Lady Westmeath, in a criminal conversation action. For once his eloquence went for nothing and despite his attacks on the characters of both Lord and Lady Westmeath, the jury awarded the enormous sum of £10000.

He earned the nickname "The little Jesuit of St. Omer" from wearing a brown coat outside a black one, and making pro-Catholic speeches. Started in 1780, his drinking club "The Order of St. Patrick" also included Catholic members along with liberal lawyers (who then had to be Protestant). The Club members were called The Monks of the Screw, as they appreciated wine and corkscrews. Curran was its "Prior" and consequently named his Rathfarnham home "The Priory". The club had no link to the Order of St. Patrick established in 1783.

In Dublin, he also was a member of Daly's Club.

A liberal Protestant whose politics were similar to Henry Grattan, he employed all his eloquence to oppose the illiberal policy of the Government, and also the Union with Britain. Curran stood as Member of Parliament (MP) for Kilbeggan in 1783. He subsequently represented Rathcormack between 1790 and 1798 and served then for Banagher from 1800 until the Act of Union in 1801, which bitterly disappointed him; he even contemplated emigrating to the United States. He also visited France in the 1780s and in 1802 at the time of the Treaty of Amiens, and considered that an Ireland ruled by the United Irishmen under French protection would be as bad as, if not worse than, British rule.

In 1798, Ireland seeing the success of the French Revolution, rebelled against the British House of Commons and lack of reforms on Catholic Emancipation. The British were able to defeat the Irish rebels and at the battles of Ballinahinch, Vinegar Hill, and Ballinamuck although reinforced by the French under General Humbert, and soon establish their control over the country by 1799. Many ring leaders were charged with treason and were facing death sentences and Curran played an important role in court defending the leaders of the United Irishmen.

Later Curran's daughter's romanced with a leader of the United Irishmen, Robert Emmet, made a good excuse to arrest Curran, but Curran was not found of participating in the Rebellion and was released and his daughter's lover was found guilty of rebelling against the Crown and the union between Great Britain and Ireland and was hanged in 1803.

However, he defended several of the United Irishmen in prominent high treason cases in the 1790s. Among them were the Revd. William Jackson, Archibald Hamilton Rowan, Wolfe Tone, Napper Tandy, The Sheares Brothers, Lord Edward Fitzgerald, William Orr, Peter Finnerty and William Drennan. His difficulty in defending treason cases was that the Dublin administration could rely upon one witness to secure a conviction, while in England the law required that the prosecution had to use two or more witnesses. Consequently, his success depended on his lengthy examination of a single witness to try to find an inconsistency. He used this technique to great effect in the case of Patrick Finney, a Dublin tobacconist charged with treason in 1798, largely on the evidence of one James O'Brien. Curran destroyed O'Brien's credit and the judges, for once in sympathy with the accused, virtually ordered an acquittal. In the same year he unsuccessfully defended the journalist Peter Finnerty for seditious libel in publishing an attack on the judges who heard the William Orr case, and the Lord Lieutenant. Despite an eloquent speech by Curran, Finnerty was found guilty and sentenced to two years imprisonment.

In 1797 he was condemned as "the leading advocate of every murderer, ruffian and low villain".

In 1802, Curran won damages from Major Sirr, who in 1798 had arrested Irish revolutionaries Lord Edward FitzGerald, Thomas Russell and Robert Emmet. Curran spoke for a Protestant, who had volunteered against the Rebellion but had happened to cross Sirr by convincing a jury of the "infamous" character of Sirr's witness in a treason trial, so causing Sirr's case to collapse. Sirr and his colleague were alleged then to have used wrongful arrest, imprisonment incommunicado, and condemnation to hanging as means to extortion and personal satisfaction. Curran implied that these were typical of their methods and of the methods used to suppress the Rebellion. Niles' Register of 24 March 1821 describes Sirr as "this old sinner, given to eternal infamy by the eloquence of Curran'".

His youngest daughter Sarah's romance with the rebel Robert Emmet, who was hanged for treason in 1803, scandalised Curran, who had tried to split them up. He was arrested and agreed to pass their correspondence on to Standish O'Grady, 1st Viscount Guillamore, the Attorney General for Ireland. In the circumstances he could not defend Emmet. He was suspected with involvement in Emmet's Rebellion, but was completely exonerated. However, his friend Lord Kilwarden was killed by the rebels, and he lost any faith in the beliefs of the United Irishmen. He disowned Sarah, who died of tuberculosis five years later.

He was appointed Master of the Rolls in Ireland in 1806, following Pitt's replacement by a more liberal cabinet.

He retired in 1814 and spent his last three years in London. He died in his home in Brompton in 1817. In 1837, his remains were transferred from Paddington Cemetery, London to Glasnevin Cemetery, where they were laid in an 8-foot-high classical-style sarcophagus. In 1845 a white marble memorial to him, with a carved bust by Christopher Moore, was placed near the west door of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin.

Reading Curran's courtroom defense of the United Irishmen, Karl Marx was so impressed that he accounted Curran "the only great lawyer (people's advocate) of the eighteenth century and the noblest personality" (Henry Grattan, by comparison, he judged a "parliamentary rogue").

In 1774, Curran married his cousin Sarah Creagh (1755–1844), the daughter of Richard Creagh, a County Cork physician. His eldest daughter Amelia was born in 1775, and eight more children resulted from the union, but his marriage disintegrated, his wife eventually deserting him and eloping with Reverend Abraham Sandys, whom Curran sued afterwards for criminal conversation in 1795.

In Dublin, he was a member of Daly's Club.

Curran was appointed Master of the Rolls in Ireland in 1806, following Pitt's replacement by a more liberal cabinet.

Quotations and Legacy

A restated version of John Curran's quote is engraved into a statue in Washington D.C.

"I have never yet heard of a murderer who was not afraid of a ghost." - A retort to a unionist MP who spoke of how he shuddered each time he passed the now-empty Parliament House, Dublin. The MP had voted in favour of the Act of Union which abolished the Irish Parliament.

"Assassinate me you may; intimidate me you cannot."

"His smile is like the silver plate on a coffin."

"In this administration, a place can be found for every bad man."

"Twenty four millions of people have burst their chains, and on the altar erected by despotism for public slavery, have enthroned the image of public liberty" – Speaking of the French Revolution, 4 February 1790.

"It is the common fate of the indolent to see their rights become a prey to the active. The condition upon which God hath given liberty to man is eternal vigilance; which condition if he break, servitude is at once the consequence of his crime and the punishment of his guilt." – Speech upon the Right of Election for Lord Mayor of Dublin, 1790, as quoted in Bartlett's Familiar Quotations

"No matter with what solemnities he may have been devoted on the altar of slavery, the moment he touches the sacred soil of Britain, the altar and the god sink together in the dust; his soul walks abroad in her own majesty; his body swells beyond the measure of his chains which burst from around him, and he stands redeemed, regenerated, and disenthralled, by the irresistible genius of universal emancipation." – (Curran's speech in defence of James Somersett, a Jamaican slave who declared his freedom upon being brought to Britain [where slavery was banned] by his master; quoted extensively by US abolitionists such as Harriet Beecher Stowe in Uncle Tom's Cabin, Chapter 37. Frederick Douglass always recited this speech on stage when playing Curran.)

"Evil prospers when good men do nothing." (Also attributed to Edmund Burke; the quote cannot be definitely traced to either man.)

Judge: (whose wig was awry, to Curran) Curran, do you see anything ridiculous in this wig?

Curran: Nothing but the head, my lord!

"My dear doctor, I am surprised to hear you say that I am coughing very badly, as I have been practising all night."

"When I can't talk sense, I talk metaphor."

"Everything I see disgusts and depresses me: I look back at the streaming of blood for so many years, and everything everywhere relapsed into its former degradation – France rechained, Spain again saddled for the priests, and Ireland, like a bastinadoed elephant, kneeling to receive the paltry rider." – Written in a letter, after the exile of Napoleon Bonaparte.

"If sadly thinking, with spirits sinking,

Could more than drinking my cares compose,

A cure for sorrow my sighs would borrow

And hope tomorrow would end my woes.

But as in wailing there's naught availing

And Death unfailing will strike the blow

And for that reason, and for a season,

Let us be merry before we go.

To joy a stranger, a wayworn ranger,

In every danger my course I've run

Now hope all ending, and death befriending,

His last aid lending, my cares are done.

No more a rover, or hapless lover,

My griefs are over – my glass runs low;

Then for that reason, and for a season,

Let us be merry before we go." – ("The Deserter's Meditation")

"O Erin how sweetly thy green bosom rises,

An emerald set in the ring of the sea,

Each blade of thy meadows my faithful heart prizes,

Thou queen of the west, the world's cushla ma chree."

His witticisms

One night, Curran was dining with Justice Toler, a notorious "hanging judge".

Toler: Curran, is that hung-beef?

Curran: Do try it, my lord, then it is sure to be!

A wealthy tobacconist, Lundy Foot, asked Curran to suggest a Latin motto for his coach. "I have just hit on it!', exclaimed Curran. "It is only two words, and it will explain your profession, your elevation, and your contempt for the people's ridicule; it has the advantage of being in two languages, Latin and English, just as the reader chooses. Put up "Quid Rides" upon your carriage!" (A quid was a lump of tobacco to be chewed, and also slang for a sovereign (stg£1); "rides" is Irish slang for "has sexual intercourse"; in Latin "Quid rides" means: "so you may laugh").

Curran hated the Act of Union, which abolished the Parliament of Ireland and amalgamated it with that of Great Britain. The parliament had been housed in a splendid building in College Green, Dublin, which faced an uncertain future. "Curran, what do they mean to do with this useless building? For my part, I hate the very sight of it!" said one lord, who was for the Act of Union. "I do not wonder at it, my lord", said Curran contemptuously. "I have never yet heard of a murderer who is not afraid of a ghost."

Curran arrived at court late one morning. The judge, Viscount Avonmore, demanded an explanation. "On my way to court, I passed through the market—" "Yes, I know, the Castle Market," interrupted Lord Avonmore. "Exactly, the Castle Market, and passing near one of the stalls, I beheld a brawny butcher brandishing a sharp gleaming knife. A calf he was about to slay was standing, awaiting the deathstroke, when at that moment—that critical moment—a lovely little girl came bounding along in all her sportive mirth from her father's stall. Before a moment had passed the butcher had plunged his knife into the breast of—" "Good God! His child!" sobbed the judge, deeply affected. Curran carried on: "No, the calf, but your Lordship often anticipates."

A prosecutor, infuriated by Curran's insults, threatened to put him in his pocket. "If you do that," replied Curran, "you will have more law in your pocket than you ever had in your head."

In debate with John Fitzgibbon, 1st Earl of Clare, Fitzgibbon rebutted one of Curran's arguments by saying "If that be the law, Mr. Curran, I shall burn all my law books." To which he replied "You had better read them first, my lord."

On another occasion Fitzgibbon objected that Curran was splitting hairs- surely the words "also" and "likewise" have exactly the same meaning ? "Hardly, my Lord". Curran replied. "I remember when the great Lord Lifford presided over this Court. You also preside here, but you certainly do not preside likewise".

Appreciation

Lord Byron said, after the death of Curran, "I have heard that man speak more poetry than I have seen written", and, in a letter to Thomas Moore, 1 October 1821, "I feel, as your poor Curran said, before his death, 'a mountain of lead upon my heart, which I believe to be constitutional, and that nothing will remove it but the same remedy.'"

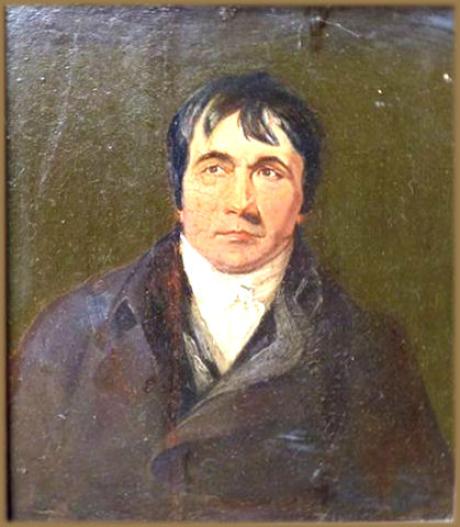

An engraved portrait of Curran by J.J. Wedgwood was published in volume one of the first Irish biographical dictionary, Biographia Hibernica, a Biographical Dictionary of the Worthies of Ireland, from the earliest periods to the present time, (London, 1819: Richard Ryan (biographer)).

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Lines on Curran's Picture (L. E. L.)

In Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1832, Letitia Elizabeth Landon includes an illustrative poem to the engraved portrait therein.

Karl Marx recommended to Friedrich Engels that he read the speeches of John Philpot Curran in a letter of 10 December 1869: "You must get Curran's Speeches edited by Davies [i.e. Thomas Davis] (London: James Duffy, 22, Paternoster Row) [...] I consider Curran the only great lawyer (people's advocate) of the eighteenth century and the noblest personality, while Grattan was a parliamentary rogue [...] You will find quoted there all the sources for the United Irishmen."

Sir Thomas Lawrence was born in Bristol. His father was an innkeeper, first at Bristol and afterwards at Devizes, and at the age of six Lawrence was already being shown off to the guests of the Bear as an infant prodigy who could sketch their likenesses and declaim speeches from Milton. In 1779 the elder Lawrence had to leave Devizes, having failed in business and Thomas's precocious talent began to be the main source of the family's income; he had gained a reputation along the Bath road.

His debut as a crayon portrait painter was made at Oxford, where he was well patronized, and in 1782 the family settled in Bath, where the young artist soon found himself fully employed in taking crayon likenesses of fashionable people at a guinea or a guinea and a half a head. In 1784 he gained the prize and silver-gilt palette of the Society of Arts for a crayon drawing after Raphael's "Transfiguration," and presently beginning to paint in oil.