By direct descent within the family of the sitter.

MB Cantab(1808) MD(1813) FRCP(1814)

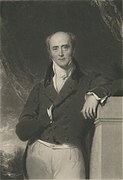

John Ayrton Paris, M.D.,was born at Cambridge, 7th August, 1785, and was the son of Thomas Paris, of Cambridge, by his wife Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Edward Ayrton, of Trinity College, doctor of music. When twelve years of age, he was placed under Mr. Barker, of Trinity hall, Cambridge, and then under Dr. Curteis, at the Grammar school of Linton. Subsequently he was removed to London, and placed under the private tuition of Dr. Bradley, one of the physicians to the Westminster hospital, an accomplished mathematician and a good classical scholar. With him he read Latin and Greek, and acquired some knowledge of botany. He was matriculated at Cambridge as a pensioner of Caius college, 17th December, 1803, and was elected to a Tancred studentship in Physic 3rd January, 1804. From the commencement of his career at Cambridge he evinced that strong predilection for natural philosophy which characterised his future life. He spent some time at Edinburgh, where, in addition to improvement in the practical part of physic, he perfected the knowledge of chemistry and natural philosophy he had acquired at Cambridge, by attendance on the lectures of Dr. Hope and Mr. Playfair. He proceeded bachelor of medicine at Cambridge 2nd July, 1808, took a licence ad practicandum from the university shortly afterwards, and then came to London.

Here he had the good fortune to attract the notice of Dr. Maton, who, struck by the extent and accuracy of his chemical knowledge, warmly espoused his interests, and constituted himself in the highest sense of the term his patron. In the early part of 1809 Dr. Maton resigned his office of physician to the Westminster hospital, and on the 14th April, Dr. Paris being then twenty-three years of age, was elected physician to that institution. He entered on the duties of his office with ardour, and soon afterwards commenced a course of lectures on Pharmaceutic chemistry. On the 11th December, 1809, he married Mary Catherine, the eldest daughter of Francis Noble, esq., of Fordham abbey, Cambridgeshire.

By his lectures and his writings, Dr. Paris had already attained a name among his contemporaries, and was regarded as one of the most rising members of his profession, when a circumstance occurred which exerted an important influence on his future career. The death, in 1813, of Dr. John Bingham Borlase, the early instructor of Sir Humphry Davy, and for many years the leading physician at Penzance, left a vacancy in that part of Cornwall, which many of the resident families were anxious to have efficiently supplied. Some influential gentlemen applied to Dr. Maton to recommend them a physician. He named Dr. Paris, who after some hesitation, was induced for a time to forego his prospects in London, and remove thither. Previously thereto he returned to Cambridge, was created doctor of medicine 6th July,1813, resigned his office at the Westminster hospital, and having on the 30th September, 1813, been admitted a Candidate of the College of Physicians, proceeded to Penzance, carrying with him letters of introduction and recommendation to the first families in Cornwall, most of which had been procured for him by Dr. Maton.

Dr. Paris’s progress in Cornwall was rapid beyond his expectations, and he was admitted on terms of friendship and intimacy with the best families in the county. He co-operated with them in every effort for the advancement of science, and he urged them to exertions which without him would not have been made. He it was who proposed, and with the co-operation of scientific friends established in the early part of 1814, the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall. Dr. Paris had never intended to make a lengthened stay in Cornwall, and in an elegant biographical sketch of his friend, the Rev. William Gregor, A.M., who had distinguished himself by the discovery of Manacchanite, or as it has since been termed Gregorite, read before the Geological Society of Cornwall, at the anniversary meeting of 1817, he announces his approaching departure, and takes an affectionate farewell of the society he had himself founded.

On Dr. Paris’s return to London, in 1817, he took up his abode in Sackville-street, but in the following year removed to Dover-street, Piccadilly. At this period he began a course of lectures on Materia Medica, at Windmill-street, which were continued for several successive years, and contributed greatly to his reputation. To a perfect knowledge of chemistry and botany, sound common sense, and a keen perception of the fallacies with which his subject in the lapse of ages had been encumbered, he added the charms of elegant language, abundant classical illustration, and a fund of anecdote, which could not fail to rouse and rivet the attention of his pupils. He soon became one of the most popular lecturers on Materia Medica in London, and attracted a considerable class, among which were many of the most distinguished physicians of the next generation.

The College of Physicians (of which he had been admitted a Fellow, 30th September, 1814) had about this time become possessed of one of the most complete collections of Materia Medica in Europe. That of Dr. Burges, presented to the College by Mr. E. A. Brande, to whom it had been bequeathed, had then recently been collated with the cabinet of Dr. Combe, purchased for that purpose; and the College, anxious to make it available for instruction and improvement, instituted (out of their own funds) an annual course of lectures on Materia Medica. The scientific attainments of Dr. Paris, and the reputation he had already acquired as a lecturer and a writer, pointed him out as the proper occupant of the new chair. In June, 1819, he entered upon the duties of the office by the delivery of a short series of lectures on the "Philosophy of the Materia Medica." The substance of these elegant discourses was introduced into the third edition of his Pharmacologia, and its publication constitutes an epoch in the history of the science and art of prescribing. Dr. Paris retained his office until 1826, in which year he took for his subject the recent additions to the Materia Medica, with all the new discoveries in chemistry which had reference to that subject. The attendance on these lectures at the new College in Pall Mall East, was so large, that numbers went away, unable to obtain even standing room in the theatre.

By his colleagues in the College of Physicians Dr. Paris was held in the highest respect. He was Censor in 1817, 1828, 1836, 1843; Consiliarius 1836 and 1843. He delivered the Harveian oration in 1833, and he was named an Elect 25th June, 1839. On the 20th March, 1844, he was elected President of the College, an office to which he was annually re-appointed, and which he continued to fill to the time of his death. Dr. Paris had long suffered from disease of the urinary organs; and although subject to frequent attacks of agonising pain, he preserved so calm an exterior, that few suspected the existence, none the degree of the malady which was bringing him to the grave. He died at his house in Dover-street, 24th December, 1856, in the seventy-second year of his age. He was buried at Woking Cemetery.

Dr. Paris’s mental powers which were naturally strong, had undergone that discipline which a complete university education and a deep study of chemistry are so well calculated to impart. His memory was large and singularly tenacious, a fact once acquired was never lost, a passage once read he could reproduce at pleasure. The leading feature of his mind was a comprehensive clearness; what he perceived he saw distinctly, what he had contemplated was present to his mind under all its different relations and with all its varied connections. He possessed a vigorous imagination and a ready wit, and was keenly alive to the facetiæ of human character. His reading had been extensive but discursive rather than deep. The impressions he had received were preserved in their primitive strength and in their original words; and his good sense and judgment led him to apply them with admirable effect. To an extensive knowledge of natural philosophy, he added a competent acquaintance with ancient and modern literature, of which his excellent memory enabled him to make the best use. He had a great command of language, and his choice of words was singularly happy. His writings are characterised by an elegance peculiarly his own. Their diffuseness, depending as it does, on the number and variety of his illustrations and the frequency and beauty of his metaphors, adds to, rather than detracts from, the pleasure of their perusal. His general attainments, conversational powers, quickness of repartee, and fund of anecdote, which he told with the happiest effect, rendered him an acquisition to any society.

Under a plain exterior he possessed many of the best qualities of our nature. To a manly straightforwardness of purpose and action, and an intense hatred of dissimulation or pretence were added considerable self-possession and marked decision of character. Those admitted to his intimacy can testify to the kindness of his disposition and the warmth of his heart. Dr. Paris’s knowledge of chemistry was extensive and profound. To this fascinating science he had early devoted himself; and he attracted notice on first settling in London by the extent and precision of his chemical attainments. These brought him into communication with Wollaston, Davy, Young, and others, when chemistry was undergoing one of the most important revolutions which its history presents, and was assuming its rank among the most exact and demonstrative of the inductive sciences. The association with these distinguished philosophers maintained his interest in that science. Notwithstanding the distractions of an increasing practice he still devoted much of his time to chemistry, and until within a short period of his death kept himself on a level with the rapid advances it was making. Although his name is not associated with any great discovery in chemistry, the respect in which he was held and the deference paid to his opinions by the first chemical philosophers of his age, suffice to attest the extent of his attainments.(1)

But Dr. Paris was the inventor of the safety bar, a simple means of preventing the premature explosion of gunpowder in blasting rocks, and obviating the destruction of lives which formerly occurred in the Cornish mines. It has come into general use there, and has proved an inestimable boon to the miner. In practical value, the safety bar is second only to the safety lamp of Davy, and like that should confer immortality on the name of its inventor. “By this simple but admirable invention,” says a writer in The Times, “Dr. Paris no doubt saved more lives than many heroes have destroyed.”

Dr. Paris’s writings are numerous and important.

A Memoir on the Physiology of the Egg. 8vo. Lond. 1810.

A Syllabus of a Course of Lectures on Pharmaceutic Chemistry. 8vo. Lond. 1811.

Pharmacologia on the History of Medicinal Substances. 12mo. Lond. 1812. 3rd edition. 8vo. Lond. 1820. 4th edition. 8vo. Lond. December, 1820. 5th edition. 8vo. Lond. 1822. 6th edition. 1825. 7th edition. 1829. 8th edition. 1833. 9th edition, wholly re-written, 1843.

A Guide to the Mount’s Bay and the Land’s End. 12mo. Penzance. 1815. (Anonymous.)

A Memoir of the Life and Scientific Labours of the Rev. William Gregor, A.M. 1817.

A Biographical Memoir of W. G. Maton, M.D. Roy. 8vo. Lond. 1838.

A Biographical Memoir of Arthur Young, Esq., Secretary to the Board of Agriculture.

Medical Jurisprudence (in conjunction with J. S. M. Fonblanque, Esq.). 3 vols. 8vo. Lond. 1823.

The Elements of Medical Chemistry, embracing only those branches of Chemical Science which are calculated to illustrate or explain the different objects of Medicine. 8vo. Lond. 1825.

A Treatise on Diet, with a view to establish on practical grounds a System of Rules for the Prevention and Cure of the Diseases incident to a disordered state of the Digestive Functions. 8vo. Lond. 1827. 5th edition. 1837.

The Life of Sir Humphry Davy, Bart. 2 vols. 8vo. Lond. 1831.

Philosophy in Sport made Science in Earnest. 3 vols, small 8vo. Lond. 1827. Anonymous. 8th edition. 1 vol. 1857.

John Ayrton Paris, FRS (7 August 1785 – 24 December 1856) was a British physician. He is a possible inventor of the thaumatrope, which he published with W. Phillips in April 1825.

Life

Paris made one of the earliest observations of occupational causes of cancer when, in 1822, he recognised that exposure to arsenic fumes might be contributing to the unusually high rate of scrotal skin cancer among men working in copper-smelting in Cornwall and Wales. He also wrote about accidents caused by explosives in mines and gave lectures on chemistry to the Royal Geological Society of Cornwall, serving as its first secretary. In 1844, he was elected president of the Royal College of Physicians, an office he held until his death. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in June 1821. Paris advocated for the use of scientifically assessed herbal preparations in medical treatment.

The exact date and location of Paris's birth are uncertain, with some sources listing August 7, 1785, and others noting either Cambridge or Edinburgh as his birthplace, a city with which he had connections.

Works

- Pharmacologia : corrected and extended, in Accordance with the London Pharmacopoeia of 1824, and with the generally advanced State of chemical Science. – New York : Duyckinck, 3rd American from the 6th London Ed. 1825 Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

- Appendix to the 8th Edition of the Pharmacologia : with some Remarks on various Criticisms upon the London Pharmacopoeia of 1836. – London : Highley, 1838. Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf

He wrote a number of substantial medical books, including Medical Jurisprudence (co-authored; 1823), a Pharmacologia which first appeared in 1820 and went through numerous editions, Elements of Medical Chemistry (1825) and a Treatise on Diet (1826). He also produced memoirs of other physicians for the Royal College, and Davy's first biography, The Life of Sir Humphry Davy (1831).

Around 1824 Paris wrote Philosophy in Sport made Science in Earnest: Being an Attempt to Implant in the Young Mind the First Principles of Natural Philosophy by the Aid of the Popular Toys and Sports of Youth. It was first published anonymously in 1827, but posthumous editions were credited to Paris. It showed how to use simple devices to demonstrate scientific principles.

- A Guide To The Mount's Bay And The Land's End: comprehending the topography, botany, agriculture, fisheries, antiquities, mining, mineralogy, and geology of western Cornwall. (1828) London: Thomas and George Underwood.

References

- ^ Herbert, Stephen. "Wheel of Life - The Thaumatrope".

- ^ Paris, Ayrton. A Guide To The Mount's Bay And The Land's End: comprehending the topography, botany, agriculture, fisheries, antiquities, mining, mineralogy, and geology of western Cornwall.

- ^ Denise Crook, ‘Paris, John Ayrton (bap. 1785, d. 1856)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, May 2007 accessed 15 Nov 2007

- ^ Paris, John Ayrton, M.D. (1785–1856), physician, by Norman Moore, Dictionary of National Biography, Published 1895

- ^ "Lists of Royal Society Fellows 1660–2007". London: The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "John Ayrton Paris". Royal College of Physicians. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

External links

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Both sides of a thaumatrope from 1825 (click for a simulation of its appearance in use)

A thaumatrope is an optical toy that was popular in the 19th century. A disk with a picture on each side is attached to two pieces of string. When the strings are twirled quickly between the fingers the two pictures appear to blend into one. The toy has traditionally been thought to demonstrate the principle of persistence of vision, a disputed explanation for the cause of illusory motion in stroboscopic animation and film.

Examples of common thaumatrope pictures include a bare tree on one side of the disk, and its leaves on the other, or a bird on one side and a cage on the other. Many classic thaumatropes also included riddles or short poems, with one line on each side.

Thaumatropes can provide an illusion of motion with the two sides of the disc each depicting a different phase of the motion, but no examples are known to have been produced until long after the introduction of the first widespread animation device: the phenakistiscope

Thaumatropes are often seen as important antecedents of motion pictures and in particular of animation.

The name translates roughly as "wonder turner", from Ancient Greek: θαῦμα "wonder" and τρόπος "turn".

Invention

A 2012 paper argues that a prehistoric bone disk found in the Laugerie-Basse rockshelter is a thaumatrope, designed to be spun using leather thongs threaded through the central perforation.

The invention of the thaumatrope is usually credited to British physician John Ayrton Paris. He described the device in his 1827 educational book for children Philosophy in Sport Made Science in Earnest, with an illustration by George Cruikshank.

British mathematician Charles Babbage recalled in 1864 that the thaumatrope was invented by the geologist William Henry Fitton. Babbage had told Fitton how the astronomer John Herschel had challenged him to show both sides of a shilling at once. Babbage held the coin in front of a mirror, but Herschel showed how both sides were visible when the coin was spun on the table. A few days later Fitton brought Babbage a new illustration of the principle, consisting of a round disc of card suspended between two pieces of sewing silk. This disc had a parrot on one side and a cage at the other side. Babbage and Fitton made several different designs and amused some friends with them for a short while. They forgot about it until some months later they heard about the "wonderful invention of Dr. Paris".

French artist Antoine Claudet stated in 1867 that he had heard that Paris had once been present when Herschel demonstrated his rotating coin trick to his children and subsequently got the idea for the thaumatrope.

Claudet also noted in 1867 that the thaumatrope could create a three-dimensional illusion. A spinning rectangular thaumatrope with the alternating letters of the name "Victoria" on each side, showed the full word with the letters at two different distances from the observer's eye. If the two strings of the thaumatrope are attached to the same side of the card the thickness of the card accounts for a small difference in the distances when each side is visible.

Commercial production

The first commercial thaumatrope was registered at Stationers' Hall on 2 April 1825 and published by W. Phillips in London as The Thaumatrope; being Rounds of Amusement or How to Please and Surprise By Turns, sold in boxes of 12 or 18 discs. It included a sheet with mottoes or riddles for each disc, often with a political meaning. Paris was widely regarded as the author, but wasn't mentioned on the product or its packaging and he later claimed in a letter to Michael Faraday "I was first induced to publish it, at the earnest desire of my late friend Wm Phillips. (...) I may add that I never put my name to it".

The steep price of a set (seven shilling for 12 discs or half a guinea for 18) was criticized, half a guinea would have been about a week's pay for an average worker. It was also defended: its inventor should be able to earn something from his invention while it was new, before it was widely copied as seen before with the kaleidoscope. Paris later claimed he gained £150,- from its sales in the United Kingdom.

As expected, pirate copies soon became common and were much cheaper. For instance the 'Thaumatropical Amusement' was available in boxes of six discs for one shilling.

Although the toy became very popular, original copies are now very rare; only one extant set produced by W. Phillips is currently known (in the Richard Balzer collection) and one single disc is at the Cinématheque Française.

Other early publishers across the continent included Alphonse Giroux & Compagnie in France and Trentsensky in Austria. In 1833 these companies would be the very first publishers of the next big "philosophical toy" craze: the Phénakisticope.

Animation

In the first 1827 edition of "Philosophy in Sport" John Ayrton Paris described a version with a circular frame around the disc through which the strings were threaded. A little tug on the strings would cause a minor change in the axis of rotation and thus a slight shift in the position of the images while revolving. An adapted version of the standard horse and jockey thaumatrope could thus first show the jockey on the horse before being thrown over its head. In a new 1833 edition of the book this example was replaced with a version without a ring but with an elastic string added to change the axis by pulling it. This version showed a drinking man lowering and raising a bottle to and from his mouth, with an illustration of the different sides of the disc and the different states of the resulting image. Several other examples were described in the book. The balls of a juggler could appear as in motion and the two painted balls could be seen as three or four when the axis of rotation was shifted. A tailor in a pulpit next to a pond with a goose fluttering in the water would have the tailor falling into the water and the goose taking his place in the pulpit. No commercially produced versions with these techniques are known.

On 26 November 1869 the Rev. Richard Pilkington received "Useful Registered Design Number 5074" for his Pedemascope. This was a variation of the thaumatrope. It had a card with pictures "painted in two different positions on both sides". This card was placed in the two-part mahogany holder with a handle and a brass pin that would semi-rotate the card when it was twirled (a bit of iron preventing full rotation). Transparent or cut-out variations were suggested for use with the magic lantern.

In 1892 mechanical engineer Thomas E. Bickle received British Patent No. 20,281 for a clockwork thaumatrope with "pictures or designs exhibiting some action or motion in two phases, which are thus alternately presented to the eye in rapid succession with small intervals of rest".

Thaumatropes in popular culture

The 1827 book Philosophy in Sport made Science in Earnest, being an attempt to illustrate the first principles of natural philosophy by the aid of popular toys and sports featured the thaumatrope and warned against inferior copies. The chapter head was illustrated with a drawing by George Cruikshank, depicting a man demonstrating the thaumatrope to a girl and a boy. It was first published anonymously, but posthumous editions were credited to John Ayrton Paris.

In the 1999 Tim Burton film Sleepy Hollow, a bird and cage thaumatrope is demonstrated by Johnny Depp's character.

In the 2006 Christopher Nolan film The Prestige, Michael Caine's character repeatedly uses a thaumatrope as a way of explaining persistence of vision.

In the 2011 Martin Scorsese film Hugo, the final scene begins in the middle of a conversation about cinema precursors, including the thaumatrope.

In the 2013 video game BioShock Infinite the bird and the cage thaumatrope is used several times.

In the 2022 film The Wonder, a thaumatrope is featured frequently throughout the film.

In the 2023 film Gaslight, a thaumatrope is used.

Sir George Hayter (17 December 1792 – 18 January 1871) was an English painter, specialising in portraits and large works involving sometimes several hundred individual portraits. Queen Victoria appreciated his merits and appointed Hayter her Principal Painter in Ordinary and also awarded him a Knighthood in 1841.

Early life

Hayter was the son of Charles Hayter (1761–1835), a miniature painter and popular drawing-master and teacher of perspective who was appointed Professor of Perspective and Drawing to Princess Charlotte and published a well-known introduction to perspective and other works.

Initially tutored by his father, he went to the Royal Academy Schools early in 1808, but in the same year, after a disagreement about his art studies, ran away to sea as a Midshipman in the Royal Navy. His father secured his release, and they came to an agreement that Hayter should assist him while pursuing his own studies.

In 1809 he secretly married Sarah Milton, a lodger at his father's house (he was 15 or 16, she 28), the arrangement remaining secret until around 1811. Together they had three children Sophia (born and died 1811), Georgiana (born 1813) and William Henry (born 1814).

At the Royal Academy Schools he studied under Fuseli, and in 1815 was appointed Painter of Miniatures and Portraits by Princess Charlotte. Hayter was awarded the British Institution’s premium for history painting for the Prophet Ezra (1815; Downton Castle), purchased by Richard Payne Knight.

Around 1816 his wife left him, for reasons which are not apparent. He subsequently began a relationship with Louisa Cauty, daughter of Sir William Cauty, with whom he lived openly for the next decade and who bore him two children, Angelo and Louisa.

Travel to Italy

Encouraged by his patron, John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, he travelled to Italy to study in 1816. There he met Canova, whose studio he attended while painting his portrait, where he absorbed Canova's classical style. He is also believed to have learned sculpture from Canova at this time. Canova was Perpetual Principal of the Accademia di San Luca (Rome's premier artistic institution) and doubtless put Hayter forward for honorary membership on the strength of his painting ‘The Tribute Money’ which was very favourably received in Rome. Hayter thereby became the Academy's youngest ever member.

Historical portraiture

Returning to London in 1818, Hayter practised as a portrait painter in oils and history painter. Dubbed ‘The Phoenix’ by William Beckford, Hayter showed a pomposity that irritated his fellow artists, but he mixed freely with many aristocratic families. His unconventional domestic life (separated from his wife, yet living with his mistress) set him apart from official Academy circles: he was never elected to the Royal Academy.

Hayter was most productive and innovative during the 1820s. George Agar-Ellis (later Lord Dover) commissioned The Trial of Queen Caroline depicting George IV's attempt to divorce Queen Caroline in the House of Lords in 1820 (exh. Cauty's Great Rooms, 80-82 Pall Mall, 1823; London, National Portrait Gallery); painted on a large scale (2.33×2.66 m), Hayter's first (and most successful) contemporary history painting revealed a taste for high drama effectively realised. In the Trial of William, Lord Russell, in the Old Bailey in 1683 (1825; Woburn Abbey) Hayter celebrated John Russell's ancestry, in a work reminiscent of fashionable tableaux vivants of the country-house set.

Return to the Continent

In 1826 Hayter settled in Italy. The Banditti of Kurdistan Assisting Georgians in Carrying off Circassian Women (untraced), completed in Florence for John Proby, 1st Earl of Carysfort (exhibited British Institution 1829), demonstrated Hayter's assimilation of the style and exotic subject-matter of contemporary French Romantic art.

In 1827 his mistress, Louisa Cauty, died after poisoning herself with arsenic. Although it was apparently an accident, in a bid for attention, it was widely assumed that he had driven her to suicide, and he was forced by the scandal to move from Florence to Rome.

By late 1828 he was in Paris, where his portraits of English society members (some exhibited at the Salon in 1831) were stylistically akin to the work of recent French portrait painters such as François Gérard.

Royal patronage

In 1831 Hayter returned to England. His grandiose plan to paint the first sitting after the passage of the Reform Bill resulted in his painting Moving the Address to the Crown on the Opening of the First Reformed Parliament in the Old House of Commons, 5 February 1833 (1833–1843; London, N.P.G.), for which he executed nearly 400 portrait studies in oil. Hayter was an ardent supporter of the reform movement and this painting was not commissioned but to all intents and purposes a labour of love. It occupied him for ten years with no guarantee of financial reward. This is one of the last images executed of the interior of the old House of Commons before its destruction in the fire of 1834. The painting was finally purchased by the government for the nation in 1854, 20 years after it was started.

Having painted the young Princess Victoria (1832–3; destr.; oil sketch, Brit. Royal Col.), Hayter was not a surprising choice as the new Queen's 'Portrait and Historical Painter'. But on the death of Sir David Wilkie in 1841 Hayter's appointment as Principal Painter in Ordinary to the Queen caused some annoyance at the Royal Academy as this appointment had historically been the preserve of the President, then Sir Martin Archer Shee. In 1842 Hayter was knighted. He painted several royal ceremonies including Queen Victoria's coronation of 1838 and marriage of 1840 and also the Christening of the Prince of Wales of 1843 (all Brit. Royal Col.). He also painted several royal portraits including his most well-known work the State Portrait of the new Queen Victoria. Several versions of this portrait were done, with the assistance of the artist's son Angelo, to be sent as diplomatic gifts. Hayter's active period at court was short-lived, however, because Albert preferred German painters such as F. X. Winterhalter.

Several significant examples of Hayter's works from this period remain a part of the Royal Collection, and both the State Portrait and Wedding painting are among those displayed to the public at Buckingham Palace. There is also a full-scale version of the State Portrait in the National Portrait Gallery and smaller copy at Holyrood House.

Later years

Now in his fifties, Hayter struggled with his health and debts and he sold his Old-Masters and other art works at Christies in May 1845. He planned to move back to the continent but could not after he received severe leg injuries in July 1845 train accident. His wife, Sarah, died in 1844, and on 12 May 1846 he married (Helena) Cecilia Hyde, née Burke (1791/2–1860). After she died in 1860, Hayter married Martha Carey, née Miller (1818–1867) on 23 April 1863. By the mid-1840s Hayter's portrait style was considered old-fashioned. He adjusted his type of history painting to suit the more literal taste of the early Victorian era (e.g. Wellington Viewing Napoleon's Effigy at Madame Tussaud's; destr. 1925; engraving, 1854).

Hayter painted several large religious paintings including two depicting important Reformist events, 'Bishop Latimer Preaching at Paul's Cross' and 'The Martyrdom of Bishops Ridley and Latimer' (exh. 1855), both of which were given to the Art Museum, Princeton University, USA in 1984. He painted several biblical scenes from the Old and New Testament, among them The Angels Ministering to Christ in 1849 (V&A) and Joseph Interpreting the Baker's Dream in 1854 (Lancaster City Museums). He also produced fluent landscape watercolours (many of Italian views), etchings (he published a volume in 1833), decorative designs and sculpture.

On 18 January 1871 Hayter died at his home in London. He was buried in St Marylebone cemetery in East Finchley. The contents of Hayter's studio were auctioned at Christie's, London, on 19 April 1871.

His younger brother, John (1800–1895), was also an artist, known chiefly as a portrait draughtsman in chalks and crayons and his younger sister Anne worked as a miniaturist. Some sources say that the influential printmaker Stanley William Hayter was a direct descendant from John Hayter, although others say the ancestor was Sir George Hayter himself. However the family tree of John and George Hayter published in Crisps Visitations shows no possible link to SW Hayter. What is known for certain is that the French painter and writer, Jean René Bazaine was a great great grandson of George Hayter, through his eldest daughter Georgiana Elizabeth, who married Pierre-Dominique Bazaine older brother of Marshal Bazaine.

Gallery

-

Princess Victoria painted 1833

-

Detail from State Portrait of Queen Victoria 1837

-

State Portrait of Queen Victoria 1837

-

The Christening of the Prince of Wales in St. George's Chapel, Windsor 25 Jan 1842

-

Marriage of Victoria and Albert, 10 February 1840

-

Queen Victoria seated on the throne in the House of Lords 1838

-

Queen Victoria seated on the throne in the House of Lords 1838 (copy commissioned by Madamme Tussauds)

-

Queen Victoria taking the Coronation Oath 1838

-

Queen Victoria taking the Coronation Oath

-

The Trial of Queen Caroline in the House of Lords 1820 (188 portraits), completed 1823

-

Queen Caroline, wife of George IV during her trial, 1820

-

The House of Commons, 1833 (375 portraits)

-

Latimer preaching at St.Paul's cross, 1855

-

The Martydom of Ridley and Latimer, 1855

-

Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool and Prime Minister, 1823 (for Trial of Queen Caroline picture)

-

General Thomas Graham, 1st Baron Lynedoch 1823

-

Duchess of Kent (mother of Queen Victoria), 1835

-

Antonio Canova painted in 1817

-

Queen Louise of Belgium, Windsor 1837

-

Edwin Landseer drawn in 1825

-

Lord Richard Cavendish as a boy, painted in 1825

-

Portrait of a young lady in an interior 1826

-

Portrait of a Lady, Naples 1828

-

Lady Stuart de Rothesay and her daughters, Paris 1830

-

Lord Stuart de Rothesay, British Ambassador to France, Paris 1830

-

The Hon. Charlotte and The Hon. Louisa Stuart, daughters of Baron Stuart de Rothesay, Paris 1830

-

Charlotte, Countess de la Bourdonnaye (1795–1875) Paris 1830

-

Saith Satoor and Ali Hassan Bey, 1831. Saith Satoor was the protégé of Prince Abbas Mirza, Crown Prince of Persia

-

Sofia Kiselyova, daughter of Count Stanislav Potocki 1831

-

The Hon. Mrs. Caroline Norton, society beauty and author, 1832

-

Louisa Philips, Countess of Lichfield (c.1800-1879) with two of her Children, Thomas George Anson and Lady Harriet Frances Maria Anson, painted in 1832

-

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey Prime Minister 1830–1834

-

Lord Melbourne Prime Minister 1834, 1835–1841

-

Robert Lawrence Pemberton of Bainbridge House with his mother

-

Anne Elphinstone 1835

-

Lady Elizabeth Harcourt, eldest daughter of 2nd Earl of Lucan and wife of George Harcourt

-

John Montagu, 7th Earl of Sandwich (1811–1884), 7th Earl of Sandwich

-

John Spencer, 3rd Earl Spencer (1782–1845)

-

Lady Louisa Stuart at the age of ninety-three, sketch in oils

-

John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford (1766–1839)

-

John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford (1766–1839)

-

Francis Baring, 1st Baron Northbrook (1833) for House of Commons picture

-

Admiral Sir Edward Codrington 1835

-

Thomas Brunton in 1832 (inventor of studded-link, marine chain cable), friend of the artist

-

The Duke of Wellington (1839), for the House of Commons picture

-

Rt Hon John Johnson, Lord Mayor of London 1845

-

Sir James Robertson-Bruce 2nd Bt painted in 1820

-

Mrs Ellen Robertson-Bruce painted in 1820

-

Portrait of a boy

-

The Angels Ministering to Christ, 1849

-

Joseph Interpreting the Dream of the Chief Baker, 1854

-

Amy Emily Sarah Fitzroy, 1858

-

Hemsted Park, three studies with trees and storm clouds, 1856