inscribed on the reverse

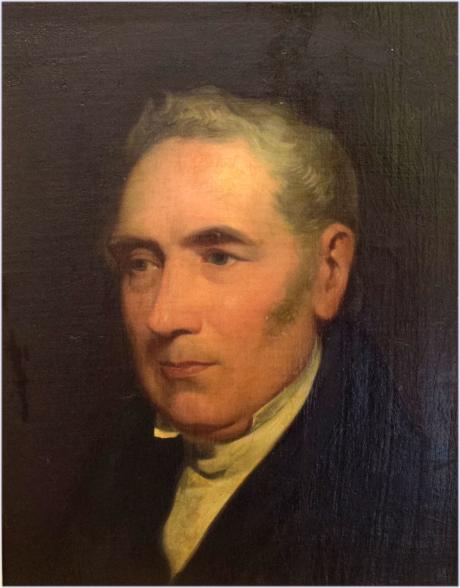

a letter accompanies this portrait from Irwen R Jewitt , it reads " Thalloch 9th March 1891 / My Dear Mr Goss / Yesterday being Sunday and being very wet and cold , I never went out but went through a lot of letters and papers and send you the resuts herewith . I hope there will be some ites of sufficient interest and reward you for the very great touble of examining them. I havent the least doubt that there is a large proportion useless matter among them. / The coloured tracings I know nothing about as there is no letter with them, they were sent to my father by Barron Broschofsky of Russia. / The portrait in a separate parcel is George Stephenson the engineer, by Jacob Thompson it is in the same state as when given to my father and very bad condition too but you will be able to restore it. It would be worth ….and pro……as an example of Jacob Thompson's work. / What a nasty return to winter this is, it will be a shock to the birds nests. Mr William Hattam is a great lover of birds and a close observer of them tells me they have been building for some time in the garden, it seems early even with best love to all./ yours very tuely / Irwen R Jewitt"

Jacob Thompson presented to Llewellyn Jewitt 1816-1886 and then to

William Henry Goss 1833 - 1906

George Stephenson (9 June 1781 – 12 August 1848) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer. Renowned as the "Father of Railways", Stephenson was considered by the Victorians a great example of diligent application and thirst for improvement. Self-help advocate Samuel Smiles particularly praised his achievements. His chosen rail gauge, sometimes called "Stephenson gauge", was the basis for the 4 feet 8+1⁄2 inches (1.435 m) standard gauge used by most of the world's railways.

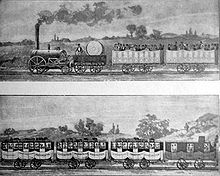

Pioneered by Stephenson, rail transport was one of the most important technological inventions of the 19th century and a key component of the Industrial Revolution. Built by George and his son Robert's company Robert Stephenson and Company, the Locomotion No. 1 was the first steam locomotive to carry passengers on a public rail line, the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825. George also built the first public inter-city railway line in the world to use locomotives, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, which opened in 1830

George Stephenson was born on 9 June 1781 in Wylam, Northumberland, which is 9 miles (15 km) west of Newcastle upon Tyne. He was the second child of Robert and Mabel Stephenson, neither of whom could read or write. Robert was the fireman for Wylam Colliery pumping engine, earning a very low wage, so there was no money for schooling. At 17, Stephenson became an engineman at Water Row Pit in Newburn nearby. George realised the value of education and paid to study at night school to learn reading, writing and arithmetic – he was illiterate until the age of 18.

In 1801 he began work at Black Callerton Colliery south of Ponteland as a 'brakesman', controlling the winding gear at the pit.In 1802 he married Frances Henderson and moved to Willington Quay, east of Newcastle. There he worked as a brakesman while they lived in one room of a cottage. George made shoes and mended clocks to supplement his income.

Their first child Robert was born in 1803, and in 1804 they moved to Dial Cottage at West Moor, near Killingworth where George worked as a brakesman at Killingworth Pit. Their second child, a daughter, was born in July 1805. She was named Frances after her mother. The child died after just three weeks and was buried in St Bartholomew's Church, Long Benton north of Newcastle.

In 1806 George's wife Frances died of consumption (tuberculosis). She was buried in the same churchyard as their daughter on 16 May 1806, though the location of the grave is lost.

George decided to find work in Scotland and left Robert with a local woman while he went to work in Montrose. After a few months he returned, probably because his father was blinded in a mining accident. He moved back into a cottage at West Moor and his unmarried sister Eleanor moved in to look after Robert. In 1811 the pumping engine at High Pit, Killingworth was not working properly and Stephenson offered to improve it. He did so with such success that he was promoted to enginewright for the collieries at Killingworth, responsible for maintaining and repairing all the colliery engines. He became an expert in steam-driven machinery.

Early projects

The Safety Lam

|

|

|

Further information: Safety lamp

In 1815, aware of the explosions often caused in mines by naked flames, Stephenson began to experiment with a safety lamp that would burn in a gaseous atmosphere without causing an explosion. At the same time, the eminent scientist and Cornishman Humphry Davy was also looking at the problem. Despite his lack of scientific knowledge, Stephenson, by trial and error, devised a lamp in which the air entered via tiny holes, through which the flames of the lamp could not pass.

A month before Davy presented his design to the Royal Society, Stephenson demonstrated his own lamp to two witnesses by taking it down Killingworth Colliery and holding it in front of a fissure from which firedamp was issuing. The two designs differed; Davy's lamp was surrounded by a screen of gauze, whereas Stephenson's prototype lamp had a perforated plate contained in a glass cylinder. For his invention Davy was awarded £2,000, whilst Stephenson was accused of stealing the idea from Davy, because he was not seen as an adequate scientist who could have produced the lamp by any approved scientific method.

Stephenson, having come from the North-East, spoke with a broad Northumberland accent and not the 'Language of Parliament,' which made him seem lowly. Realizing this, he made a point of educating his son Robert in a private school, where he was taught to speak in Standard English with a Received Pronunciation accent. It was due to this, in their future dealings with Parliament, that it became clear that the authorities preferred Robert to his father.

A local committee of enquiry gathered in support of Stephenson, exonerated him, proved he had been working separately to create the 'Geordie Lamp', and awarded him £1,000, but Davy and his supporters refused to accept their findings, and would not see how an uneducated man such as Stephenson could come up with the solution he had. In 1833 a House of Commons committee found that Stephenson had equal claim to having invented the safety lamp. Davy went to his grave believing that Stephenson had stolen his idea. The Stephenson lamp was used almost exclusively in North East England, whereas the Davy lamp was used everywhere else. The experience gave Stephenson a lifelong distrust of London-based, theoretical, scientific experts.

In his book George and Robert Stephenson, the author L.T.C. Rolt relates that opinion varied about the two lamps' efficiency: that the Davy Lamp gave more light, but the Geordie Lamp was thought to be safer in a more gaseous atmosphere. He made reference to an incident at Oaks Colliery in Barnsley where both lamps were in use. Following a sudden strong influx of gas the tops of all the Davy Lamps became red hot (which had in the past caused an explosion, and in so doing risked another), whilst all the Geordie Lamps simply went out.

There is a theory that it was Stephenson who indirectly gave the name of Geordies to the people of the North East of England. By this theory, the name of the Geordie Lamp attached to the North East pit men themselves. By 1866 any native of Newcastle upon Tyne could be called a Geordie.

Locomotives

Cornishman Richard Trevithick is credited with the first realistic design for a steam locomotive in 1802. Later, he visited Tyneside and built an engine there for a mine-owner. Several local men were inspired by this, and designed their own engines.

Stephenson designed his first locomotive in 1814, a travelling engine designed for hauling coal on the Killingworth wagonway named Blücher after the Prussian general Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher (It was suggested the name sprang from Blücher's rapid march of his army in support of Wellington at Waterloo). Blücher was modelled on Matthew Murray's locomotive Willington, which George studied at Kenton and Coxlodge colliery on Tyneside, and was constructed in the colliery workshop behind Stephenson's home, Dial Cottage, on Great Lime Road. The locomotive could haul 30 tons of coal up a hill at 4 mph (6.4 km/h), and was the first successful flanged-wheel adhesion locomotive: its traction depended on contact between its flanged wheels and the rail.

Altogether, Stephenson is said to have produced 16 locomotives at Killingworth, although it has not proved possible to produce a convincing list of all 16. Of those identified, most were built for use at Killingworth or for the Hetton colliery railway. A six-wheeled locomotive was built for the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway in 1817 but was withdrawn from service because of damage to the cast-iron rails.Another locomotive was supplied to Scott's Pit railroad at Llansamlet, near Swansea, in 1819 but it too was withdrawn, apparently because it was under-boilered and again caused damage to the track.

The new engines were too heavy to run on wooden rails or plate-way, and iron edge rails were in their infancy, with cast iron exhibiting excessive brittleness. Together with William Losh, Stephenson improved the design of cast-iron edge rails to reduce breakage; rails were briefly made by Losh, Wilson and Bell at their Walker ironworks.

According to Rolt, Stephenson managed to solve the problem caused by the weight of the engine on the primitive rails. He experimented with a steam spring (to 'cushion' the weight using steam pressure acting on pistons to support the locomotive frame), but soon followed the practice of 'distributing' weight by using a number of wheels or bogies. For the Stockton and Darlington Railway Stephenson used wrought-iron malleable rails that he had found satisfactory, notwithstanding the financial loss he suffered by not using his own patented design.

Hetton Railway

Stephenson was hired to build the 8-mile (13-km) Hetton colliery railway in 1820. He used a combination of gravity on downward inclines and locomotives for level and upward stretches. This, the first railway using no animal power, opened in 1822. This line used a gauge of 4 ft 8 in (1,422 mm) which Stephenson had used before at the Killingworth wagonway.

Other locomotives include:

- 1817–1824 The Duke for the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway

The First Railways

Stockton and Darlington Railway

In 1821, a parliamentary bill was passed to allow the building of the Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR). The 25-mile (40 km) railway connected collieries near Bishop Auckland to the River Tees at Stockton, passing through Darlington on the way. The original plan was to use horses to draw coal carts on metal rails, but after company director Edward Pease met Stephenson, he agreed to change the plans. Stephenson surveyed the line in 1821, and assisted by his eighteen-year-old son Robert, construction began the same year

A manufacturer was needed to provide the locomotives for the line. Pease and Stephenson had jointly established a company in Newcastle to manufacture locomotives. It was set up as Robert Stephenson and Company, and George's son Robert was the managing director. A fourth partner was Michael Longridge of Bedlington Ironworks. On an early trade card, Robert Stephenson & Co was described as "Engineers, Millwrights & Machinists, Brass & Iron Founders". In September 1825 the works at Forth Street, Newcastle completed the first locomotive for the railway: originally named Active, it was renamed Locomotion and was followed by Hope, Diligence and Black Diamond. The Stockton and Darlington Railway opened on 27 September 1825. Driven by Stephenson, Locomotion hauled an 80-ton load of coal and flour nine miles (14 km) in two hours, reaching a speed of 24 miles per hour (39 kilometres per hour) on one stretch. The first purpose-built passenger car, Experiment, was attached and carried dignitaries on the opening journey. It was the first time passenger traffic had been run on a steam locomotive railway.

The rails used for the line were wrought-iron, produced by John Birkinshaw at the Bedlington Ironworks. Wrought-iron rails could be produced in longer lengths than cast-iron and were less liable to crack under the weight of heavy locomotives. William Losh of Walker Ironworks thought he had an agreement with Stephenson to supply cast-iron rails, and Stephenson's decision caused a permanent rift between them. The gauge Stephenson chose for the line was 4 feet 8+1⁄2 inches (1,435 mm) which subsequently was adopted as the standard gauge for railways, not only in Britain, but throughout the world.

Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Stephenson had ascertained by experiments at Killingworth that half the power of the locomotive was consumed by a gradient as little as 1 in 260.He concluded that railways should be kept as level as possible. He used this knowledge while working on the Bolton and Leigh Railway, and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR), executing a series of difficult cuttings, embankments and stone viaducts to level their routes. Defective surveying of the original route of the L&MR caused by hostility from some affected landowners meant Stephenson encountered difficulty during Parliamentary scrutiny of the original bill, especially under cross-examination by Edward Hall Alderson. The bill was rejected and a revised bill for a new alignment was submitted and passed in a subsequent session. The revised alignment presented the problem of crossing Chat Moss, an apparently bottomless peat bog, which Stephenson overcame by unusual means, effectively floating the line across it. The method he used was similar to that used by John Metcalf who constructed many miles of road across marshes in the Pennines, laying a foundation of heather and branches, which became bound together by the weight of the passing coaches, with a layer of stones on top.

As the L&MR approached completion in 1829, its directors arranged a competition to decide who would build its locomotives, and the Rainhill Trials were run in October 1829. Entries could weigh no more than six tons and had to travel along the track for a total distance of 60 miles (97 km). Stephenson's entry was Rocket, and its performance in winning the contest made it famous. George's son Robert had been working in South America from 1824 to 1827 and returned to run the Forth Street Works while George was in Liverpool overseeing the construction of the line. Robert was responsible for the detailed design of Rocket, although he was in constant postal communication with his father, who made many suggestions. One significant innovation, suggested by Henry Booth, treasurer of the L&MR, was the use of a fire-tube boiler, invented by French engineer Marc Seguin that gave improved heat exchange.

The opening ceremony of the L&MR, on 15 September 1830, drew luminaries from the government and industry, including the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington. The day started with a procession of eight trains setting out from Liverpool. The parade was led by Northumbrian driven by George Stephenson, and included Phoenix driven by his son Robert, North Star driven by his brother Robert and Rocket driven by assistant engineer Joseph Locke. The day was marred by the death of William Huskisson, the Member of Parliament for Liverpool, who was struck by Rocket. Stephenson evacuated the injured Huskisson to Eccles with a train, but he died from his injuries. Despite the tragedy, the railway was a resounding success. Stephenson became famous, and was offered the position of chief engineer for a wide variety of other railways.

Stephenson's skew arch bridge

1830 also saw the grand opening of the skew bridge in Rainhill over the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. The bridge was the first to cross any railway at an angle. It required the structure to be constructed as two flat planes (overlapping in this case by 6 ft (1.8 m)) between which the stonework forms a parallelogram shape when viewed from above. It has the effect of flattening the arch and the solution is to lay the bricks forming the arch at an angle to the abutments (the piers on which the arches rest). The technique, which results in a spiral effect in the arch masonry, provides extra strength in the arch to compensate for the angled abutments.

The bridge is still in use at Rainhill station, and carries traffic on the A57 (Warrington Road). The bridge is a listed structure.

Jacob Thompson, eldest son of Merrick Thompson, a manufacturer of linen check and a well-known member of the Society of Friends, was born in Lanton Street, Penrith, Cumberland, on 28 August 1806. His father was then in prosperous circumstances, but the depression of trade caused by the War of 1812 brought about his failure. Young Thompson's aspirations to become an artist met with little sympathy from his family, and he was apprenticed to a house-painter; but he struggled with energy and perseverance against these adverse influences, and devoted all his leisure time to his favourite pursuit. He at length attracted the notice of Lord Lonsdale, and with his help he came in 1829 to London with an introduction to Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830), and became a student at the British Museum and the Royal Academy

Thompson began to exhibit in 1824, when he had in the first exhibition of the Society of British Artists a "View in Cumberland," but he did not send a picture to the Royal Academy until 1832, in which year appeared "The Druids Cutting Down the Mistletoe". This was followed in 1833 by a picture containing full-length portraits of the daughters of the Hon. Colonel Lowther. His next exhibit was "Harvest Home in the Fourteenth Century," which appeared at the British Institution in 1837, and was presented by the artist to his patron, the Earl of Lonsdale. After this date he painted portraits, views of mansions, etc., but he did not exhibit again until 1847, when he sent to Westminster Hall "The Highland Ferry-Boat," which was engraved in line by James Tibbits Willmore. "The Proposal" appeared at the Royal Academy in 1848; "The Highland Bride," likewise engraved by Willmore, in 1851; "Going to Church: Scene in the Highlands," in 1852; "The Hope Beyond," in 1853; "The Course of true Love never did run smooth," in 1854; "The Mountain Ramblers," in 1855; "Sunny Hours of Childhood" and "Looking out for the Homeward Bound," in 1856; and "The Pet Lamb," in 1857. He painted in 1858 "Crossing a Highland Loch," which was engraved by Charles Mottram; but he did not again exhibit until 1860, when he sent to the Royal Academy "The Signal," which was engraved by Charles Cousen for the Art Journal of 1862. In 1864, he had at the academy "The Height of Ambition," engraved by Charles Cousen for the Art Journal, as was likewise by J. C. Armytage "Drawing the Net at Hawes Water," painted in 1867 for Lord Esher, but never exhibited. "Rush Bearing" and a view of Rydal Mount are among his best works

In his later years, Thompson devoted himself chiefly to landscape subjects with figures, the themes of which were for the most part drawn from the mountains and lakes of Cumberland and Westmoreland, but occasionally from Scotland. His range, however, was limited, and his work was lacking in poetic sympathy. His attempts at classical and scriptural subjects, such as "Acis and Galatea," exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1849, and "Proserpine," were not a success. His last work was "Eldmuir, or Solitude."

Thompson was married twice; his first wife, Ann Parker Bidder, was a sister of George Parker Bidder, the celebrated calculating prodigy and civil engineer. Thompson and his first wife had one son. After his first wife died in 1844, Thompson remarried in 1850 to Elizabeth Varty.Thompson died at the Hermitage—a cottage on the estate of Lord Lonsdale —in Hackthorpe, Cumberland, where he had lived in retirement for upwards of 40 years, on 27 December 1879. He was buried in the churchyard at St. Michael's Church in Lowther.

The Life and Works of Jacob Thompson (1882) by Llewellyn Jewitt includes a portrait of Thompson, drawn on wood by himself, and engraved by W. Ballingall, in the prefix.

In 1999, "The Highland Ferry-Boat" was sold at auction for £166,500 in Gleneagles, Scotland.

Penrith and Eden Museum has works by Thompson on display, including "The Druids Cutting Down the Mistletoe", which shows figures in a wooded clearing in the Eden Valley with the Bronze Age stone circle of Long Meg and Her Daughters, one of Eden’s iconic monuments and tourist destinations, clearly visible in the distance.

Gallery

-

Portrait of William Lowther, 1st Earl of Lonsdale