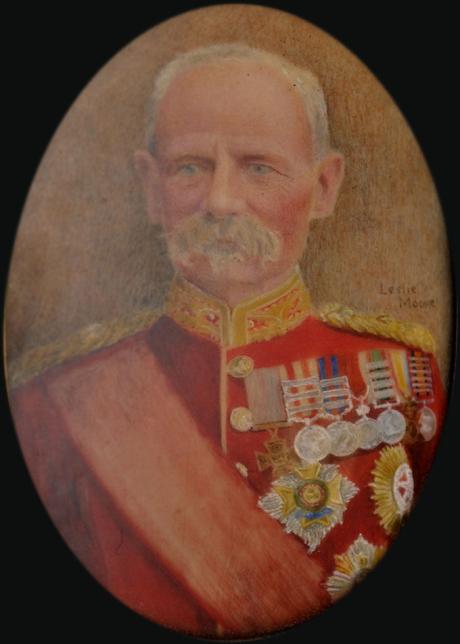

Leslie Moore

Roberts, Frederick Sleigh, first Earl Roberts (1832–1914), army officer, was born on 30 September 1832 at Cawnpore, India, the younger son of Sir Abraham Roberts (1784–1873), commanding the East India Company's Bengal European regiment, and his second wife, Isabella (d. 1882), widow of Major Hamilton Maxwell and daughter of Abraham Bunbury, of Kilfeacle, co. Tipperary; Roberts's family were Anglo-Irish on both sides. He was christened Sleigh after the garrison commander at Cawnpore (Major-General William Sleigh).

Abraham Roberts brought his family home to England in 1834 and, before returning to India, settled them at Clifton, the family home for the next forty years. Frederick went to Eton College in 1845 but stayed only a year before going to the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, in January 1847. He wanted to join the British army but his father, largely on grounds of expense, preferred him to enter the East India Company's service and after two years at Sandhurst he entered the company's military college at Addiscombe, Croydon, in February 1850. He passed out ninth of his class in November 1851, and was commissioned into the Bengal artillery on 12 December 1851. He landed at Calcutta on 1 April 1852, and was posted to a battery at Peshawar, where his father commanded the Peshawar division. Until Abraham Roberts went home at the end of 1853, Fred, as he was known in the family, served also as his aide-de-camp. He received the coveted Bengal horse artillery ‘jacket’ in 1854 and transferred to a horse artillery troop at Peshawar, his only unit command. In 1856 he was appointed to the quartermaster-general (India)'s department as acting deputy assistant quartermaster-general at Peshawar.

When news reached Peshawar of the mutinies at Meerut and Delhi on 10 and 11 May 1857 Roberts was appointed to the staff of the mobile column formed under Neville Bowles Chamberlain. In June 1857 he volunteered for the siege of Delhi. He served as a staff, as well as a battery, officer, and was incapacitated for a month by a spent bullet which hit his spine—the only wound of his career. When the city fell at the end of September 1857 he joined the staff of the force under the new commander-in-chief, Sir Colin Campbell, assembled for the second relief of Lucknow. At Khudaganj in January 1858 he won the Victoria Cross for saving the life of a loyal sepoy and capturing a rebel standard. He was present at the capture of Lucknow in March 1858, but his health was breaking down and in April 1858 he handed over his staff appointment to Garnet Wolseley and returned to England on leave. He had gained a reputation as a gallant and efficient officer.

During his leave Roberts met Nora Henrietta Bews (1838–1920), daughter of Captain John Bews, late of the 73rd regiment. They were married on 17 May 1859; their marriage was happy and supportive; they had six children, of whom three died in infancy. His wife was taller than Roberts, and a forceful woman. In later years when he held high command she apparently enjoyed power and influence over him. In India it was believed that officers could gain advancement through her, and Roberts and she were nicknamed Sir Bobs and Lady Jobs (Beckett, 478). The queen wrote in 1895 that Roberts was ‘ruled by his wife who is a terrible jobber … her notorious favouritism’ (ibid.). When in the South African War she accompanied Roberts at his headquarters despite the queen's objection, there was talk of ‘petticoat government’. Presumably the 1954 destruction by David James, Roberts's ‘official’ biographer, of the correspondence between Roberts and his wife was to conceal her role: letters from her surviving elsewhere contain detailed discussion of military matters. Wolseley, Roberts's rival, wrote in 1895 that she was ‘the commonest and most vulgar looking old thing … I have never seen a more hideous animal’ (ibid.). In July 1859 they returned to India, where Roberts had chosen to join the quartermaster-general's department: a shrewd career move, suggested by his father, because that department was in effect the general staff of the army, responsible for operations, planning, and intelligence. There he was in contact with the leading civil and military figures in India. He was promoted to captain and given a brevet majority in 1860, and in 1863 saw active service briefly on the north-west frontier in the Ambela campaign, under Neville Chamberlain. In 1868 he went as acting quartermaster-general to the Bengal brigade, which formed part of the force commanded by Sir Robert Napier in Abyssinia. He saw no fighting but, as a mark of distinction, was chosen to carry Napier's dispatches to England, and received a brevet lieutenant-colonelcy.

As a result of the post-mutiny absorption of the Bengal artillery into the British army in 1861 Roberts was now a British army officer, but he refused command of a Royal Horse Artillery battery at Aldershot to stay on in the quartermaster-general's department. In 1871 he organized the logistics of an expedition against the Lushai people of Assam, where he had his first experience of commanding troops in action; he was then created CB. Recognized as the most promising officer in the department, in 1873 and 1874 he was acting quartermaster-general. On 1 January 1875 he was promoted to substantive colonel and became quartermaster-general India, with the temporary rank of major-general.

The arrival in 1876 of Lord Lytton as viceroy marked a turning point in Roberts's career. The Disraeli government, with Salisbury as secretary of state for India, was concerned about Russian expansion in central Asia and its effect on the amir of Afghanistan, Sher Ali, whom they suspected, mistakenly, of becoming a Russian ally. Lytton came to India charged with reaching a satisfactory agreement with Sher Ali, including the establishment of a British envoy in Afghanistan. That policy was opposed by many leading officials in India, who believed in non-interference in Afghanistan, relying on warning Russia (and the amir) that direct Russian interference would result in war: the policy of ‘masterly inactivity’. Roberts and others had long believed in a ‘forward policy’ which would control the border peoples and the main passes. That policy fitted Lytton's, and Roberts quickly became his close friend and adviser. Lytton proposed to reorganize the frontier administration and to make Roberts one of two chief commissioners. Pending approval of this reorganization, Lytton appointed Roberts to command the Punjab frontier force in April 1878. After a tour of inspection Roberts returned to spend the summer at Simla to discuss the proposed reorganization. He was thus on hand when the crisis with Sher Ali erupted. Following the unwelcome arrival of a Russian mission in Kabul, Sher Ali refused to accept a British mission, which was forcibly turned back in the Khyber Pass. The British declared war in November 1878.

Three columns were organized to invade Afghanistan: the first, under Donald Stewart, a close friend of Roberts, to occupy Kandahar, the second, under Sir Sam Browne to threaten Kabul via the Khyber Pass, and the third to occupy the Kurram valley and threaten Kabul. Roberts, on Lytton's insistence and despite the opposition of the commander-in-chief India (Sir Frederick Haines), was appointed to command the Kurram column. When war was declared on 21 November 1878 he quickly occupied the Kurram valley and on 2 December, by a daring night march, defeated the Afghan force holding the Peiwar Kotal, the northern exit from the valley. A subsequent expedition into Khost was unsuccessful, and in June 1879 the first phase of the war ended with the treaty of Gandamak. Roberts's friend and ally Sir Louis Cavagnari was sent as envoy to Kabul, and Roberts returned to Simla to join a commission on the organization and financing of the Indian armies. For his war services he was made KCB.

Roberts had expressed misgivings about the safety of Cavagnari's mission, which was massacred in Kabul on 3 September. Of the three original columns only the Kurram column was available to advance on Kabul to avenge Cavagnari's death. It was the major turning point of Roberts's career. In just over a month he had occupied Kabul, defeating en route a large Afghan force on the Charasia heights outside the city. He chose wisely not to base his force on the Bala Hissar fortress inside the city but to occupy an unfinished cantonment at Sherpur, north of the city. A military commission was set up to try those responsible for Cavagnari's death. The executions which followed caused a political storm in England, led by Liberals and by humanitarians including John Morley, Lord Ripon, Samuel Wilberforce, C. H. Spurgeon, and J. A. Froude. Even Lytton was uneasy, although Roberts was acting on his orders. Afghan opposition coalesced quickly and early in December 1879, after unsuccessful actions, Roberts was besieged in Sherpur. On 23 December he repulsed a huge assault and reoccupied the city.

Doubts had been raised after the executions about Roberts's political judgement, and in the spring of 1880 Stewart marched from Kandahar to Kabul to assume the chief command, to Roberts's chagrin. Negotiations had already begun to recognize Sher Ali's nephew, Abdur Rahman, as amir and to evacuate the troops when news reached Kabul of the defeat of a British brigade at Maiwand, west of Kandahar, on 27 July 1880, by another claimant to the amirate, Ayub Khan. Roberts pressed immediately for a force to go from Kabul to relieve the garrison of Kandahar and, government having approved, he left Kabul with a picked force of 10,000 on 8 August. He reached Kandahar on 31 August after a march of 313 miles and on the following day decisively defeated Ayub Khan. Roberts was made GCB and was appointed commander-in-chief of the Madras army. The drama of the march to Kandahar and the crushing victory caught the public's imagination and turned Roberts into a public hero and a rival to Wolseley. But, as he himself recognized, the march was not as great a military feat as his advance on Kabul a year earlier, and it was by no means the smooth operation of legend. Nevertheless, he had emerged as a field commander of the first rank.

Roberts came home on leave to regain his health in the autumn of 1880 and quickly found himself in public dispute with Wolseley, then adjutant-general, on short versus long service. In March 1881 he was sent at short notice to South Africa after the defeat at Majuba, but on arriving he found that a treaty had already been signed. He came straight back to England, where he received a baronetcy and a grant of £12,500 in the Second Anglo-Afghan War honours list. Proposals to make him quartermaster-general of the British army having come to nothing, he left for India in November 1881 to take up the Madras command.

The Madras command confirmed Roberts in his view that only the ‘martial races’ of northern India provided suitable fighting material. He wrote papers on the Russian threat and Indian defence, and on British army recruitment. Increasingly he was seen as a counterbalance to Wolseley by those who distrusted the latter and his ‘ring’ of officers, since Roberts was technically eligible for the highest posts of the British army. Then and later he carefully cultivated close relations with politicians including Lord Randolph Churchill, Salisbury, and Lansdowne, and with editors and journalists—including William Blackwood, and C. F. Moberly Bell of The Times—and military writers, notably, later, Spenser Wilkinson. His succession as commander-in-chief in India, although widely expected, was not assured and it took a carefully timed retirement by Donald Stewart and Roberts's contact with Lord Randolph Churchill, then secretary of state for India, to secure the post in July 1885. From the 1880s there was rivalry between Roberts and Wolseley, who loathed him, and between networks of officers, Wolseley's ring and Roberts's Indians. Wolseley and ring members, among themselves, accused Roberts of self-advertisement, snobbery, and jobbery. The duke of Cambridge also distrusted Roberts, perceiving him as an intriguing, unscrupulous opportunist.

Roberts was commander-in-chief for an unprecedented eight years, and was thus able to shape the Indian armies' organization, training, and operational planning. He was moreover involved with the Third Anglo-Burmese War, exercising direct command there between November 1886 and February 1887. But his primary concern remained defence against a Russian attack from the north and north-west. His strategic plan involved the speedy occupation of the Kandahar–Kabul line, and a major programme of fortification and improvements to communications along the frontier was carried out; a series of military expeditions extended control over the trans-border tribes. Improvements in training, especially in musketry, and re-equipment with new weapons, including machine guns, were also undertaken. Perhaps the most significant achievement long term was in altering the ethnic composition of the Indian army in favour of the ‘martial races’ of the north. He also improved conditions of the British soldiers, and encouraged temperance among the other ranks.

His earlier conviction that the short-service system did not meet imperial needs came gradually to be tempered by realization that a long-service system was incapable of producing the massive reinforcements for a war with Russia. Much of the apparent difference between him and Wolseley on this issue was due to Indian strategy requiring instantly available, trained reinforcements, with quality rather than numbers, whereas Wolseley envisaged fighting Russia in Europe where the emphasis would be on numbers.

Roberts was created Baron Roberts of Kandahar in January 1892 and, resisting efforts to prolong his tenure, left India in April 1893. No suitable appointment was immediately available, and he compiled his memoirs. Forty-one Years in India (1897) was a stirring story, not unbiased, which became a popular success and remains a useful historical source. This was an uneasy time for Roberts, despite his public honours. When he sought further employment Campbell-Bannerman, the secretary of state for the army, told W. E. Gladstone: ‘Roberts … is a good soldier … but he is an arrant jobber, and intriguer, and self-advertiser and altogether wrong in his political opinions, both British and “Indian”’ (Gladstone, Diaries, 13.259n).

In May 1895 Roberts was promoted field marshal, and in the October succeeded Wolseley in the undemanding Irish command. By early 1899 he was approaching final retirement but still hankered for a command in the field. In August 1899, with war in South Africa looming, he invited Lord Kitchener to Ireland to make his acquaintance. Though very different they got on well, and Kitchener made it clear that if Roberts were offered a field command he would be willing to serve as his chief of staff.

When war with the Boers broke out in October 1899 Sir Redvers Buller was sent to South Africa in overall command. Roberts was unimpressed by Buller, a member of Wolseley's ring, and by his strategy, and at the beginning of December 1899, through his friend Lansdowne, offered his services to the government. On 16 December, following the defeats at Colenso, Stormberg, and Magersfontein (‘black week’), the government bowed to pressure and appointed Roberts to succeed Buller, with Kitchener as chief of staff. Roberts arrived in London the following day to be greeted with the news of the death of his only son. Lieutenant Frederick Roberts (b. 1872), King's Royal Rifle Corps, died from wounds suffered at Colenso when trying to rescue the guns: he was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Roberts and Kitchener reached Cape Town on 10 January 1900 to face a difficult situation. In Natal a large British force under Sir George White, a protégé of Roberts, was besieged in Ladysmith, which Buller was trying to relieve. In the centre Sir William Gatacre had been defeated at Stormberg, and Boer forces were poised to invade Cape Colony. In the west Lord Methuen had been defeated at Magersfontein, where Piet Cronje's main Orange Free State army also threatened Cape Colony. Moreover, the British troops had proved inferior to the Boers in mobility, shooting, and tactics: defects which Roberts could not remedy quickly. The pressing need was to seize the initiative and relieve the pressure in Natal and on Cape Colony.

Roberts had considered a plan of campaign for South Africa as early as 1897, and developed this on the voyage out. His plan was essentially simple but characteristically bold: Buller was to stand on the defensive in Natal while Roberts concentrated all available forces behind Methuen on the line of the westernmost railway, from Cape Town to Kimberley, where a force was besieged. The cavalry, under Sir John French, was to ride round the left flank of Cronje's force on the Modder River, to seize Kimberley, while the infantry pinned down the Boer army. With Kimberley secured Roberts planned to move eastwards to seize Bloemfontein and then move northwards along the railway line to seize Johannesburg and Pretoria. He hoped thus to force the Boers onto the defensive and to bring their main forces to battle. To implement this plan he needed to increase his mobile forces, so he raised two new mounted regiments of local volunteers and 3000 mounted infantry from the regular infantry.

Exactly four weeks after landing at Cape Town, Roberts had concentrated a force of 37,000 men, including a cavalry division of 5000, at Ramdam, on the railway line some 20 miles south of the Modder River. In concentrating this force Roberts and Kitchener had broken up the system of regimental and brigade transport and centralized all transport: a controversial decision. The forthcoming campaign was hampered by the inadequacy of the supply system. On 11 February 1900 French and the cavalry set out on the long ride past Cronje to Kimberley, followed by most of the infantry. On 15 February French entered Kimberley. Apart from losing a substantial proportion of the army's supplies, the operation had gone as planned. Cronje, retreating eastward towards Bloemfontein, was trapped on the Modder River at Paardeburg. Kitchener, in temporary command because Roberts was ill, launched a costly and unsuccessful assault. Roberts, on reassuming direct command, used siege tactics, and Cronje, with more than 4000 men, surrendered on 27 February.

Supply problems prevented an immediate advance on Bloemfontein, and when Roberts finally moved forward he found the remaining free state forces occupying an extended position at Poplar Grove covering the capital. The Boer forces, numbering some 14,000, were accompanied by their presidents, Kruger and Steyn. Roberts's plan was to send the cavalry round the Boers' southern flank to cut their line of retreat while the infantry attacked frontally. The cavalry advance on 7 March was sluggish, partly from shortage of supplies and poor horsemastership, and the Boers evaded the trap. It was probably the last opportunity for the war to have been quickly ended. Bloemfontein was occupied on 13 March. This marked a decisive reversal in the strategic situation. Ladysmith had finally been relieved on 28 February, and Buller was now in a position to clear Natal and co-operate in an advance on Pretoria. In the centre, Gatacre and Clements had crossed the Orange River and linked up with Roberts's troops south of Bloemfontein on 16 March. The strategic initiative had passed to the British, nine weeks after Roberts had arrived and four weeks after the start of his offensive.

Roberts was detained at Bloemfontein for six weeks by a combination of supply problems, a typhoid (enteric) epidemic, and the breakdown of medical services—which arguably he could have done more to rectify—the need to repair the railway, and the daring attacks by de Wet east and south-east of the capital. Roberts renewed his advance on 3 May. Moving on a broad front and manoeuvring the Boers out of successive positions, he advanced through the Orange Free State into Transvaal. He occupied Johannesburg on 31 May but by a serious error of judgement allowed the Boer forces under Louis Botha to evacuate the town with guns and supplies. Pretoria was occupied on 5 June and the main Boer force under Botha defeated at Diamond Hill, east of Pretoria, on 12 June. Kruger and his government had already fled towards Portuguese East Africa. Machadodorp was occupied on 28 July, by which time Buller had at last linked up with Roberts. Koomati Port was occupied on 24 September, and no important town remained in Boer hands. Kruger fled to Europe.

The formal annexation of the Transvaal on 25 October 1900, following that of the Orange Free State on 28 May, appeared to mark the end of the war, even though significant bodies of Boers, under such leaders as Steyn, de Wet, and De La Rey, were still at large and had begun guerrilla operations. To counter the guerrillas Roberts ordered the selective destruction of Boer farms, as reprisals and for resource denial.

Roberts's operations since landing in January had been dramatically successful; in some nine months he had advanced about 500 miles, defeated the main enemy armies, and occupied their capitals. Although the war dragged on another two years, its issue was no longer in doubt. But the operations had not been an unqualified success. Apart from Cronje's surrender Roberts had failed to trap any large part of the Boer forces or to inflict a major defeat in the field. Opportunities had been lost, as at Poplar Grove, partly from a logistics failure, for which he was ultimately responsible. Above all he underestimated the Boers: an error of judgement shared by virtually every other politician and general. Probably no other contemporary British general could have bettered or even equalled Roberts's achievement, at the age of sixty-seven.

On 29 September 1900 Roberts had been offered the post of commander-in-chief of the British army in succession to Wolseley, and on 29 November he handed over command in South Africa to Kitchener, and sailed on 11 December. On reaching England he received the Order of the Garter, an earldom, and a grant of £100,000. However, his tenure was to prove disappointing, overshadowed by controversy about the role of the commander-in-chief and the organization of the War Office. Nevertheless, much useful reform was achieved, utilizing his experience from India and South Africa. A new rifle—the magazine Lee-Enfield—was introduced for all units, including the cavalry, for whom it was intended to be the primary weapon, the lance being abolished. On the controversial issue of the cavalry arme blanche Roberts wanted its minimal use. New ordnance, improved vehicles, and khaki service dress were introduced, and training was improved under a new department of military training and education.

The achievements of Roberts's tenure as commander-in-chief were, however, overshadowed by the long-standing problem of the role of the commander-in-chief and the need for a general staff. In 1891 the Hartington commission had recommended the abolition of the post of commander-in-chief and its replacement by that of a chief of staff. Roberts believed that the commander-in-chief should be solely responsible to the secretary of state for the efficiency of the army, and that the adjutant-general and the quartermaster-general should be responsible directly to him; the last should revert to intelligence and operational planning, his logistic functions being taken over by a director-general of supply and transport, thus effectively creating a general staff, which he had long favoured. The report of the royal commission on the war in South Africa showed that the existing organization had to be changed, and in the autumn of 1903 Lord Esher chaired a new commission on War Office organization. Its report in February 1904 recommended the abolition of the post of commander-in-chief and the creation of an army board. These proposals were not alien to Roberts's own thinking, but they provided no place for him. A blunder resulted in his post as commander-in-chief being abolished without his being informed, and he left the War Office in February 1904.

Roberts initially accepted a seat on the new committee of imperial defence but soon disagreed with Balfour's government over compulsory military training. His espousal of it owed something to his South African experience and perhaps more initially to the insufficient forces available to defend India against Russia. The Russian threat diminished after 1905, and was replaced by the apparent threat of German invasion of Britain. Failing to convince the government on compulsion, Roberts resigned from the committee in November 1905.

Roberts was one of the most famous men of his era, immensely admired, a popular imperial hero—celebrated in biographies, verse, pottery, and picture postcards, and featured in early news films—and much honoured with British and foreign orders and honorary degrees, colonelcies, and civic distinctions. In November 1905 Roberts became president of the National Service League, the organization founded by the duke of Wellington, George F. Shee, and others in 1902, which campaigned for compulsory military training. Until August 1914 Roberts devoted himself to the league, which he helped to revive and change from a little-known pressure group to a significant force in British public life, and whose figurehead and leading spokesman he became. He participated in the controversy on sea power and invasion. He travelled the country addressing mass meetings, advocating national service, and warning against the German threat, and he supported compulsion bills in the House of Lords. Perhaps unwisely, he assisted William Le Queux with the sensational anti-German fiction ‘The invasion of 1910’, published in Northcliffe's Daily Mail in 1906. The league met strong opposition, including from the Liberal government and its war minister, R. B. Haldane. In 1910 Ian Hamilton, then adjutant-general, in co-operation with Haldane, published Compulsory Service, attacking Roberts's views: a personal blow to Roberts, as Hamilton had long been his protégé and friend. Roberts, with L. S. Amery and Professor J. A. Cramb (who largely wrote Roberts's National Service League speeches), replied with Fallacies and Facts (1911).

Although Roberts tried to keep the league above party politics most of its members were Unionists, and Roberts was tory and a ‘die-hard’ in opposing the Parliament Bill in 1911. Himself Anglo-Irish, he opposed Irish home rule and actively supported the Ulster Unionists. He chose the commander of the Ulster Volunteer Force and, opposing the use of the army to coerce Ulster, was involved in the Curragh incident of March 1914.

On the outbreak of war in 1914 Roberts attended the council of war on the destination of the British expeditionary force. Appointed colonel-in-chief of the empire (‘overseas’) troops in France, while visiting Indian troops there he died of pneumonia at 52 rue Carnot, St Omer, on 14 November 1914. He was buried in St Paul's Cathedral on 19 November. Lady Roberts died in 1920, and at the death of their daughter Edwina, Countess Roberts, in 1955, the title became extinct.

Small, wiry, and an excellent horseman, Roberts possessed that invaluable quality of generalship, good physical health, as well as great personal charm and kindliness. Fluent and persuasive on paper, he was not quick in debate, and he was not basically an original thinker, preferring to move forward on the basis of previous experience. The popular image of the little, simple, upright soldier, the chevalier sans peur et sans reproche, owed more to Rudyard Kipling's hero-worship (as in his poem ‘Bobs’) than to reality. His surviving papers reveal a more complex character—ambitious, manipulative, on occasions devious, and with a strong political awareness.

Roberts was perhaps the ablest field commander since Wellington—quick to grasp a situation, bold and decisive in his solutions, and calm and confident in the face of difficulties. But he was prone to underestimate his opponents and to take risks, particularly with logistics. His performance in South Africa at the age of sixty-seven suggests that he had the potential to be one of the great commanders, but it was never tested in a European theatre. About his stature as a commander there will continue to be debate.

Brian Robson DNB