Theatre scholars have been fascinated by Edmund Kean since his death in 1833, aged 45. It is partly because he single-handedly changed the way Shakespeare was acted at the time and partly because he went from near destitution to fame and fortune virtually overnight. Kean’s relatively short working life was every bit as dramatic as his stage performances. Not only was his rise to stardom extraordinarily rapid but, once perched at the top of the tree, he proceeded to behave very badly indeed. “He was one of the first great celebrities of Georgian England, but he had no idea how to deal with it,” says Hughes, who is also a Shakespearean scholar. “He was earning £50 a night at a time when the average annual income was £30. He spent the money on whores and booze, and towards the end of his career regularly appeared drunk on stage.”

In terms of his acting, Kean replaced the lifeless posturing and declaiming of his predecessors with a level of passion, urgency and energy that hadn’t previously been seen on the London stage. His signature performances were Richard III, Hamlet, Shylock and Iago, as well as the role of the villainous Sir Giles Overreach in A New Way to Pay Old Debts (1633). “Restraint was alien to him,” writes Giles Playfair in his 1983 biography, The Flash of Lightning. “He was flashy, all energy and passion and he needed the big scene to show off his real powers.”

Ian Hughes agrees: “He used a lot of carefully honed tricks. He wasn’t above gabbling a long speech until he got to a key phrase. Classical acting up to that point had been dull and dry. Kean introduced what became known as ‘passionate realism’. Even in his heyday, people didn’t go to see Shakespeare, they went to see Kean doing Shakespeare.”

Jane Austen refers to his popularity in a letter to her sister Cassandra, dated March 4, 1814. She wrote: “Places are secured at Drury Lane for Saturday, but so great is the rage for seeing Kean that only a third or fourth row could be got.” The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, describing the experience of seeing Kean for the first time, wrote: “To see him act is like reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning.” The critic William Hazlitt said his Iago was “the most perfect piece of acting on the stage, the most complete absorption of the man in the character”.

Kean’s theatrical apprenticeship was a long one, starting in childhood. At the age of eight he could recite the whole of The Merchant of Venice from memory, and he appeared on stage with Charles Kemble, the leading tragedian of his day, aged six as Fleance in Macbeth. In his youth he toured the provinces with second-rate travelling companies, playing barns and fairgrounds, as well as theatres, walking everywhere between engagements. Because out-of-town audiences expected all-round entertainment, he also learnt about clowning, acrobatics, timing a laugh, singing, dancing and mimicry. At 5ft 6in and slight of build, Kean’s intention to become a heroic tragedian was met mostly with derision, although he was engaged to play Hamlet in York at the age of 14. Traditionally, successful Shakespearean actors tended to be tall and aristocratic like Kemble and Henry Irving. He was talent-spotted in the provinces by Samuel Arnold, the manager of Drury Lane Theatre, and contracted to play Shylock in The Merchant of Venice in 1814. Off stage, Kean was a quiet, unassuming figure but as soon as he stepped on to the Drury Lane stage, he had the audience enraptured. Hazlitt reported in the next day’s Morning Chronicle that “no actor had come out for many years at all equal to him”. Hughes first became interested in Kean after buying an 1867 biography from David Drummond’s Theatre Bookshop off Leicester Square. He says: “It was this florid account of a man who went from grinding poverty and years of hardship to become the country’s most celebrated actor. Then he lost it all and was dead at 45. It’s an extraordinary story.”

Edmund Kean’s next part was Richard III, in the heavily revised version by Colley Cibber (1671-1757), the text which was used from the time of Garrick and still currently staged at the time of Kean21. Again Hazlitt attended the performance at Drury Lane and wrote two reviews in The Morning Chronicle on February 15th and 21st 1814. Until then, Hazlitt was the only London theatre critic who to have seen and written about Edmund Kean22. Hazlitt’s first review, dated February 15th, referring to Kean’s discovery part in Shylock, does not hesitate to pinpoint some defects, before qualifying him as an « admirable tragedian » :

Mr. Kean’s manner of acting this part has one peculiar advantage ; it is entirely his own, without any traces of imitation of any other actor. He stands upon his own ground, and he stands firm upon it. Almost every scene had the stamp and freshness of nature. The excellences and defects of his performance were in general the same as those which he discovered in Shylock ; though as the character of Richard is the most difficult, so we think he displayed most power in it. It is possible to form a higher conception of this character (we do not mean from seeing other actors, but from reading Shakespeare) than that given by this very admirable tragedian23 ;

21Hazlitt insists on the fact that Kean did not in any way endeavour to imitate successful experiences from the past ; his interpretation of the character was completely different from the current interpretation of Richard that was praised by his contemporaries. Though he did note that Kean’s performance was not without « defects » yet Hazlitt greatly appreciated this new, highly challenging rendering of the part and paid tribute to the actor’s talent. In his second review, dated February 21st 1814, Hazlitt testified that the approval was general from an enthusiastic audience for a new-born star playing to a full house : « The house was crowded at an early hour in every part, to witness Mr. Kean’s second representation of Richard. His admirable acting received that meed of applause, which it so well deserved24. »

22Kean had been playing in London for less than a month, and had already managed to attract vast numbers of theatre-goers who, according to Hazlitt’s most useful comment, took care to arrive « at an early hour ». Indeed, at the beginning of the 19th century theatre tickets sold at half price when the performance was half finished, and thus a good number of theatre-goers attended only the second half of a performance. With this detail, that can pass unnoticed now that we have different habits, Hazlitt suggested that, thanks to his own positive accounts in particular, expectations were running very high and theatre-goers were ready to pay full price to attend the whole performance. In view of the custom of this age this was a sure sign of success. Hazlitt’s unconditional admiration for the interpretation and the ability of the actor must have played a significant part in this success, and even if did point out a few defects of in Kean’s acting style, these comments can only be interpreted as an objective remark on the part of the reviewer for a very young, upcoming performer.

23With overnight success in the two consecutive Shakespearean parts of Shylock and Richard III, Kean’s reputation as a tragedian was so well established on the London stage that audiences and reviewers alike expected him to perform other Shakespearean titles-roles.

Richard III is a historical play by William Shakespeare believed to have been written around 1593. It depicts the Machiavellian rise to power and subsequent short reign of King Richard III of England.[1] The play is grouped among the histories in the First Folio and is most often classified as such. Occasionally, however, as in the quarto edition, it is termed a tragedy. Richard III concludes Shakespeare's first tetralogy (also containing Henry VI parts 1–3).

It is the second longest play in the canon after Hamlet and is the longest of the First Folio, whose version of Hamlet is shorter than its Quarto counterpart. The play is often abridged; for example, certain peripheral characters are removed entirely. In such instances, extra lines are often invented or added from elsewhere in the sequence to establish the nature of characters' relationships. A further reason for abridgment is that Shakespeare assumed that his audiences would be familiar with his Henry VI plays and frequently made indirect references to events in them, such as Richard's murder of Henry VI or the defeat of Henry's queen, Margaret.

The play begins with Richard (called "Gloucester" in the text) standing in "a street", describing the re-accession to the throne of his brother, King Edward IV of England, eldest son of the late Richard, Duke of York, implying the year is 1471.

Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York;

And all the clouds that lour'd upon our house

In the deep bosom of the ocean buried.

("Sun of York" is a punning reference to the badge of the "blazing sun", which Edward IV adopted, and "son of York", i.e. the son of the Duke of York.)

Richard is an ugly hunchback who is "rudely stamp'd", "deformed, unfinish'd", and cannot "strut before a wanton ambling nymph." He responds to the anguish of his condition with an outcast's credo: "I am determined to prove a villain / And hate the idle pleasures of these days." Richard plots to have his brother Clarence, who stands before him in the line of succession, conducted to the Tower of London over a prophecy he bribed a soothsayer to finagle the suspicious King with; that "G of Edward's heirs the murderer shall be", which the king interprets as referring to George of Clarence (without realising it actually refers to Gloucester).

Richard now schemes to woo "the Lady Anne" – Anne Neville, widow of the Lancastrian Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales. He confides to the audience:

I'll marry Warwick's youngest daughter.

What, though I kill'd her husband and her father?

The scene then changes to reveal Lady Anne accompanying the corpse of the late king Henry VI, along with Trestle and Berkeley, on its way to be interred at St Paul's cathedral. She asks them to set down the "honourable load – if honour may be shrouded in a hearse", and then laments the fate of the house of Lancaster. Richard suddenly appears and demands that the "unmanner'd dog" carrying the hearse set it down, at which point a brief verbal wrangling takes place.

Despite initially hating him, Anne is won over by his pleas of love and repentance and agrees to marry him. When she leaves, Richard exults in having won her over despite all he has done to her, and tells the audience that he will discard her once she has served her purpose.

The atmosphere at court is poisonous: The established nobles are at odds with the upwardly mobile relatives of Queen Elizabeth, a hostility fueled by Richard's machinations. Queen Margaret, Henry VI's widow, returns in defiance of her banishment and warns the squabbling nobles about Richard. Queen Margaret curses Richard and the rest who were present. The nobles, all Yorkists, reflexively unite against this last Lancastrian, and the warning falls on deaf ears.

Richard orders two murderers to kill Clarence in the tower. Clarence, meanwhile, relates a dream to his keeper. The dream includes vivid language describing Clarence falling from an imaginary ship as a result of Gloucester, who had fallen from the hatches, striking him. Under the water Clarence sees the skeletons of thousands of men "that fishes gnawed upon". He also sees "wedges of gold, great anchors, heaps of pearl, inestimable stones, unvalued jewels". All of these are "scatterd in the bottom of the sea". Clarence adds that some of the jewels were in the skulls of the dead. He then imagines dying and being tormented by the ghosts of Warwick (Anne's father), and Edward of Westminster (Anne's deceased husband).

After Clarence falls asleep, Brakenbury, Lieutenant of the Tower of London, enters and observes that between the titles of princes and the low names of commoners, there is nothing different but the "outward fame", meaning that they both have "inward toil" whether rich or poor. When the murderers arrive, he reads their warrant (issued in the name of the King), and exits with the Keeper, who disobeys Clarence's request to stand by him, and leaves the two murderers the keys.

Clarence wakes and pleads with the murderers, saying that men have no right to obey other men's requests for murder, because all men are under the rule of God not to commit murder. The murderers imply Clarence is a hypocrite because, as one says, "thou ... unripped'st the bowels of thy sovereign's son [Edward] whom thou wast sworn to cherish and defend." Trying to win them over by tactics, he tells them to go to his brother Gloucester, who will reward them better for his life than Edward will for his death. One murderer insists Gloucester himself sent them to perform the bloody act, but Clarence does not believe him. He recalls the unity of Richard Duke of York blessing his three sons with his victorious arm, bidding his brother Gloucester to "think on this and he will weep". Sardonically, a murderer says Gloucester weeps millstones – echoing Richard's earlier comment about the murderers' own eyes weeping millstones rather than "foolish tears" (Act I, Sc. 3).

Next, one of the murderers explains that his brother Gloucester hates him, and sent them to the Tower to kill him. Eventually, one murderer gives in to his conscience and does not participate, but the other killer stabs Clarence and drowns him in "the Malmsey butt within". The first act closes with the perpetrator needing to find a hole to bury Clarence.

Richard uses the news of Clarence's unexpected death to send Edward IV, already ill, into his deathbed, all the while insinuating that the Queen is behind the execution of Clarence. Edward IV soon dies, leaving as Protector his brother Richard, who sets about removing the final obstacles to his accession. He has Lord Rivers murdered to further isolate the Queen and to put down any attempts to have the Prince crowned right away. He meets his nephew, the young Edward V, who is en route to London for his coronation accompanied by relatives of Edward's widow (Lord Hastings, Lord Grey, and Sir Thomas Vaughan). These Richard arrests, and eventually beheads, and then has a conversation with the Prince and his younger brother, the Duke of York. The two princes outsmart Richard and match his wordplay and use of language easily. Richard is nervous about them, and the potential threat they are. The young prince and his brother are coaxed (by Richard) into an extended stay at the Tower of London. The prince and his brother the Duke of York prove themselves to be extremely intelligent and charismatic characters, boldly defying and outsmarting Richard and openly mocking him.

Assisted by his cousin Buckingham, Richard mounts a campaign to present himself as the true heir to the throne, pretending to be a modest, devout man with no pretensions to greatness. Lord Hastings, who objects to Richard's accession, is arrested and executed on a trumped-up charge of treason. Together, Richard and Buckingham spread the rumour that Edward's two sons are illegitimate, and therefore have no rightful claim to the throne; they are assisted by Catesby, Ratcliffe, and Lovell. The other lords are cajoled into accepting Richard as king, in spite of the continued survival of his nephews (the Princes in the Tower).

Richard asks Buckingham to secure the death of the princes, but Buckingham hesitates. Richard then recruits Sir James Tyrrell, who kills both children. When Richard denies Buckingham a promised land grant, Buckingham turns against Richard and defects to the side of Henry, Earl of Richmond, who is currently in exile. Richard has his eye on his niece, Elizabeth of York, Edward IV's next remaining heir, and poisons Lady Anne so he can be free to woo the princess. The Duchess of York and Queen Elizabeth mourn the princes' deaths, when Queen Margaret arrives. Queen Elizabeth, as predicted, asks Queen Margaret's help in cursing. Later, the Duchess applies this lesson and curses her only surviving son before leaving. Richard asks Queen Elizabeth to help him win her daughter's hand in marriage, but she is not taken in by his eloquence, and eventually manages to trick and stall him by saying she will let him know her daughter's answer in due course.

The increasingly paranoid Richard loses what popularity he had. He soon faces rebellions led first by Buckingham and subsequently by the invading Richmond. Buckingham is captured and executed. Both sides arrive for a final battle at Bosworth Field. Prior to the battle, Richard is visited by the ghosts of his victims, all of whom tell him to "Despair and die!" after which they wish victory upon Richmond. He awakes screaming for "Jesus" to help him, slowly realising that he is all alone in the world, and cannot even pity himself.

At the Battle of Bosworth Field, Lord Stanley (who is also Richmond's stepfather) and his followers desert Richard's side, whereupon Richard calls for the execution of George Stanley, Lord Stanley's son. This does not happen, as the battle is in full swing, and Richard is left at a disadvantage. Richard is soon unhorsed on the field at the climax of the battle, and cries out, "A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!" Richmond kills Richard in the final duel. Subsequently, Richmond succeeds to the throne as Henry VII, and marries Princess Elizabeth from the House of York.

Richard III is believed to be one of Shakespeare's earlier plays, preceded only by the three parts of Henry VI and perhaps Titus Andronicus and a handful of comedies. It is believed to have been written c. 1592–1594. Although Richard III was entered into the Register of the Stationers' Company on 20 October 1597 by the bookseller Andrew Wise, who published the first Quarto (Q1) later that year (with printing done by Valentine Simmes), Christopher Marlowe's Edward II, which cannot have been written much later than 1592 (Marlowe died in 1593), is thought to have been influenced by it. A second Quarto (Q2) followed in 1598, printed by Thomas Creede for Andrew Wise, containing an attribution to Shakespeare on its title page.[4] Q3 appeared in 1602, Q4 in 1605, Q5 in 1612, and Q6 in 1622, the frequency attesting to its popularity. The First Folio version followed in 1623.

The Folio is longer than the Quarto and contains some fifty additional passages amounting to more than two hundred lines. However, the Quarto contains some twenty-seven passages amounting to about thirty-seven lines that are absent from the Folio]:p.2 The two texts also contain hundreds of other differences, including the transposition of words within speeches, the movement of words from one speech to another, the replacement of words with near-synonyms, and many changes in grammar and spelling]:p.2

Unlike his previous tragedy Titus Andronicus, the play avoids graphic demonstrations of physical violence; only Richard and Clarence are shown being stabbed on-stage, while the rest (the two princes, Hastings, Brackenbury, Grey, Vaughan, Rivers, Anne, Buckingham, and King Edward) all meet their ends off-stage. Despite the villainous nature of the title character and the grim storyline, Shakespeare infuses the action with comic material, as he does with most of his tragedies. Much of the humour rises from the dichotomy between how Richard's character is known and how Richard tries to appear.

A scene from Richard III, directed by Keith Fowler for the Virginia Shakespeare Festival in Williamsburg, site of the first Shakespearean performances in America. (Here Richard is stabbed with a boar spear by the Earl of Richmond.)

Richard himself also provides some dry remarks in evaluating the situation, as when he plans to marry Queen Elizabeth's daughter: "Murder her brothers, then marry her; Uncertain way of gain ..." Other examples of humour in this play include Clarence's reluctant murderers, and the Duke of Buckingham's report on his attempt to persuade the Londoners to accept Richard ("I bid them that did love their country's good cry, God save Richard, England's royal king!" Richard: "And did they so?" Buckingham: "No, so God help me, they spake not a word ...") Puns, a Shakespearean staple, are especially well represented in the scene where Richard tries to persuade Queen Elizabeth to woo her daughter on his behalf.

Queen Margaret: "Thou elvish-mark'd, abortive, rooting hog!" Act 1, Scene III. The boar was Richard's personal symbol: Bronze boar mount thought to have been worn by a supporter of Richard III.[6]

One of the central themes of Richard III is the idea of fate, especially as it is seen through the tension between free will and fatalism in Richard's actions and speech, as well as the reactions to him by other characters. There is no doubt that Shakespeare drew heavily on Sir Thomas More's account of Richard III as a criminal and tyrant as inspiration for his own rendering. This influence, especially as it relates to the role of divine punishment in Richard's rule of England, reaches its height in the voice of Margaret. Janis Lull suggests that "Margaret gives voice to the belief, encouraged by the growing Calvinism of the Elizabethan era, that individual historical events are determined by God, who often punishes evil with (apparent) evil".[7]:p.6–8

Thus it seems possible that Shakespeare, in conforming to the growing "Tudor Myth" of the day, as well as taking into account new theologies of divine action and human will becoming popular in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, sought to paint Richard as the final curse of God on England in punishment for the deposition of Richard II in 1399.[7]:p.6–8 Irving Ribner argued that "the evil path of Richard is a cleansing operation which roots evil out of society and restores the world at last to the God-ordained goodness embodied in the new rule of Henry VII".[8]:p.62

Scholar Victor Kiernan writes that this interpretation is a perfect fit with the English social perspective of Shakespeare's day: "An extension is in progress of a privileged class's assurance of preferential treatment in the next world as in this, to a favoured nation's conviction of having God on its side, of Englishmen being ... the new Chosen People".[9]:p.111–112 As Elizabethan England was slowly colonising the world, the populace embraced the view of its own Divine Right and Appointment to do so, much as Richard does in Shakespeare's play.

However, historical fatalism is merely one side of the argument of fate versus free will. It is also possible that Shakespeare intended to portray Richard as "a personification of the Machiavellian view of history as power politics".p.6–8 In this view, Richard is acting entirely out of his own free will in brutally taking hold of the English throne. Kiernan also presents this side of the coin, noting that Richard "boasts to us of his finesse in dissembling and deception with bits of Scripture to cloak his 'naked villainy' (I.iii.334–8) ...Machiavelli, as Shakespeare may want us to realise, is not a safe guide to practical politics".p.111–112

Kiernan suggests that Richard is merely acting as if God is determining his every step in a sort of Machiavellian manipulation of religion as an attempt to circumvent the moral conscience of those around him. Therefore, historical determinism is merely an illusion perpetrated by Richard's assertion of his own free will. The Machiavellian reading of the play finds evidence in Richard's interactions with the audience, as when he mentions that he is "determinèd to prove a villain" (I.i.30). However, though it seems Richard views himself as completely in control, Lull suggests that Shakespeare is using Richard to state "the tragic conception of the play in a joke. His primary meaning is that he controls his own destiny. His pun also has a second, contradictory meaning—that his villainy is predestined—and the strong providentialism of the play ultimately endorses this meaning".:p.6–8

Literary critic Paul Haeffner writes that Shakespeare had a great understanding of language and the potential of every word he used.[10]:p.56–60 One word that Shakespeare gave potential to was "joy". This is employed in Act I, Scene III, where it is used to show "deliberate emotional effect".:p.56–60 Another word that Haeffner points out is "kind", which he suggests is used with two different definitions.

The first definition is used to express a "gentle and loving" man, which Clarence uses to describe his brother Richard to the murderers that were sent to kill him. This definition is not true, as Richard uses a gentle façade to seize the throne. The second definition concerns "the person's true nature ... Richard will indeed use Hastings kindly—that is, just as he is in the habit of using people—brutally".[10]:p.56–60

Haeffner also writes about how speech is written. He compares the speeches of Richmond and Richard to their soldiers. He describes Richmond's speech as "dignified" and formal, while Richard's speech is explained as "slangy and impetuous".[10]:p.56–60 Richard's casualness in speech is also noted by another writer. However, Lull does not make the comparison between Richmond and Richard as Haeffner does, but between Richard and the women in his life. However, it is important to the women share the formal language that Richmond uses. She makes the argument that the difference in speech "reinforces the thematic division between the women's identification with the social group and Richard's individualism".[7]:p.22–23 Haeffner agrees that Richard is "an individualist, hating dignity and formality".:p.56–60

Janis Lull also takes special notice of the mourning women. She suggests that they are associated with "figures of repetition as anaphora—beginning each clause in a sequence with the same word—and epistrophe—repeating the same word at the end of each clause".:p.22–23 One example of the epistrophe can be found in Margaret's speech in Act I, Scene III. Haeffner refers to these as few of many "devices and tricks of style" that occur in the play, showcasing Shakespeare's ability to bring out the potential of every word.:p.56–60

Richard as anti-hero

Throughout the play, Richard's character constantly changes and shifts and, in doing so, alters the dramatic structure of the story.

Richard immediately establishes a connection with the audience with his opening monologue. In the soliloquy he admits his amorality to the audience but at the same time treats them as if they were co-conspirators in his plotting; one may well be enamored of his rhetoric[11] while being appalled by his actions. Richard shows off his wit in Act I, as seen in the interchanges with Lady Anne (Act I, Scene II) and his brother Clarence (Act I, Scene I). In his dialogues Act I, Richard knowingly refers to thoughts he has only previously shared with the audience to keep the audience attuned to him and his objectives. In 1.1, Richard tells the audience in a soliloquy how he plans to claw his way to the throne—killing his brother Clarence as a necessary step to get there. However, Richard pretends to be Clarence's friend, falsely reassuring him by saying, "I will deliver you, or else lie for you" (1.1.115); which the audience knows—and Richard tells the audience after Clarence's exit—is the exact opposite of what he plans to do.:p.37 Scholar Michael E. Mooney describes Richard as occupying a "figural position"; he is able to move in and out of it by talking with the audience on one level, and interacting with other characters on another.:p.33

Each scene in Act I is book-ended by Richard directly addressing the audience. This action on Richard's part not only keeps him in control of the dramatic action of the play, but also of how the audience sees him: in a somewhat positive light, or as the protagonist. :p.32–33 Richard actually embodies the dramatic character of "Vice" from medieval morality plays—with which Shakespeare was very familiar from his time—with his "impish-to-fiendish humour". Like Vice, Richard is able to render what is ugly and evil—his thoughts and aims, his view of other characters—into what is charming and amusing for the audience.:p.38

In the earlier acts of the play, too, the role of the antagonist is filled by that of the old Lancastrian queen, Margaret, who is reviled by the Yorkists and whom Richard manipulates and condemns in Act I, Scene III.

However, after Act I, the number and quality of Richard's asides to the audience decrease significantly, as well as multiple scenes are interspersed that do not include Richard at all,:p.44 but average Citizens (Act II, Scene III), or the Duchess of York and Clarence's children (Act II, Scene II), who are as moral as Richard is evil. Without Richard guiding the audience through the dramatic action, the audience is left to evaluate for itself what is going on. In Act IV, Scene IV, after the murder of the two young princes and the ruthless murder of Lady Anne, the women of the play—Queen Elizabeth, the Duchess of York, and even Margaret—gather to mourn their state and to curse Richard; and it is difficult as the audience not to sympathise with them. When Richard enters to bargain with Queen Elizabeth for her daughter's hand—a scene whose form echoes the same rhythmically quick dialogue as the Lady Anne scene in Act I—he has lost his vivacity and playfulness for communication; it is obvious he is not the same man.]:p.32–33

By the end of Act IV everyone else in the play, including Richard's own mother, the Duchess, has turned against him. He does not interact with the audience nearly as much, and the inspiring quality of his speech has declined into merely giving and requiring information. As Richard gets closer to seizing the crown, he encloses himself within the world of the play; no longer embodying his facile movement in and out of the dramatic action, he is now stuck firmly within it]:p.47 It is from Act IV that Richard really begins his rapid decline into truly being the antagonist. Shakespeare scholar Stephen Greenblatt notes how Richard even refers to himself as "the formal Vice, Iniquity" (3.1.82), which informs the audience that he knows what his function is; but also like Vice in the morality plays, the fates will turn and get Richard in the end, which Elizabethan audiences would have recognised.

In addition, the character of Richmond enters into the play in Act V to overthrow Richard and save the state from his tyranny, effectively being the instantaneous new protagonist. Richmond is a clear contrast to Richard's evil character, which makes the audience see him as such

African-American James Hewlett as Richard III in a c. 1821 production. Below him is quoted the line "Off with his head; so much for Buckingham", a line not from the original play but from adaptations. The earliest certain performance occurred on 16 or 17 November 1633, when Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria watched it on the Queen's birthday. Colley Cibber produced the most successful of the Restoration adaptations of Shakespeare with his version of Richard III, at Drury Lane starting in 1700. Cibber himself played the role till 1739, and his version was on stage for the next century and a half. It contained the lines "Off with his head; so much for Buckingham" – possibly the most famous Shakespearean line that Shakespeare did not write – and "Richard's himself again!". The original Shakespearean version returned in a production at Sadler's Wells Theatre in 1845.

John Sartain

Kean, Edmund (1787–1833), actor, was born on 4 November 1787 in the Gray's Inn chambers of his maternal grandfather, George Saville Carey, who lived in shabby gentility on his earnings as a lecturer and entertainer. Kean's date of birth and parentage have both been disputed. His mother, Ann Carey (d. 1833), divided her time between acting and prostitution. Her grandfather, the playwright Henry Carey, was an illegitimate son of George Savile, marquess of Halifax, after whom her father was named. The likelihood is that Kean'sfather was Edmund Kean (d. 1793), at that time articled to a surveyor. This Edmund was the youngest of three brothers. Little is known of Aaron, the eldest, beyond the fact that he was frequently drunk. The second, Moses, a moderately successful entertainer, was the unmarried partner of a Drury Lane actress, Charlotte Tidswell. Edmund, who shared Aaron's dependence on alcohol, committed suicide in 1793, and the evidence suggests that Ann Carey, who had two other children by a man named Darnley, found her new son burdensome.

A loveless childhood

Kean's childhood, particularly after the death in 1792 of his uncle Moses, was loveless. He was shipped between the homes of Mrs Price, his mother's widowed sister, and Charlotte Tidswell, without being welcome in either. When possible they farmed him out with strangers, and their attempts to educate him were half-hearted. It was, nevertheless, Charlotte (‘Aunt Tid’) who most strongly influenced him during his migratory childhood. The duke of Norfolk may have interceded to procure her initial engagement at Drury Lane, and it was on rumours of her liaison with him that Keanwould later build the fiction of his aristocratic parentage. Charlotte was sufficiently competent to sustain her place at Drury Lane until 1822, when she retired at the age of sixty. It was with her that Kean first observed the backstage life of London's leading theatre.

The smatterings of information about Kean's childhood rarely rise above the anecdotal level. Aunt Tid may well have listened to, and even refined, his early recitations from Shakespeare; she may have licensed his occasional appearances, from infancy through boyhood, on the Drury Lane stage. The problem is that Kean's first three biographers shared with their subject a talent for embroidery that enforces scepticism. Bryan Waller Procter (Barry Cornwall), the first to produce a systematic life of Kean (1835), shrewdly observes in the records of his boyhood a tendency to run away when the going became tough. This was an unattractive characteristic that would remain with him. But Procter, although more circumspect than Hawkins and Molloy, had also to rely on the sort of stories that friends had heard from a friend of Kean's, and Kean in his cups was capable of wild inventiveness. It may, then, be doubted that he ever walked from Southwark to Portsmouth, where he embarked as a cabin-boy on a Madeira-bound ship, or that, at the age of four, he had to wear leg-irons because of the brutality of his acrobatic training at Drury Lane (if he ever did wear irons, incipient rickets is a likelier cause). It is, however, quite plausible that he exhibited his precocious talents anywhere from middle-class drawing-rooms to East End taverns. Ann Carey made money however she could, and there was obviously something captivating about the small, dark-eyed, and athletic boy. Perhaps with the agreement of Aunt Tid, he was marketed as an infant prodigy. A surviving playbill, dating from 1801, advertises the appearance at the Great Room, no. 8, Store Street, Bedford Square, of 'The Celebrated Theatrical Child, Edmund Carey, not eleven years old'. Kean, like the Infant Phenomenon in Nicholas Nickleby, was small enough to pass as some years younger than his true age. His later contempt for Master Betty, the sensation of the London season of 1804, may hark back to this period in the life of ‘Master Carey’.

Early struggles

Kean may have made a few undistinguished appearances on the Drury Lane stage before the end of the eighteenth century. He had certainly experienced the seedier life of a strolling player, perhaps with his mother as a member of the Saunders company, perhaps with John Richardson, who had pitched his first portable booth-theatre at Bartholomew fair in 1798. It was as a tumbler that Kean was featured at such fairs, one among the crowd:

Pimps, pawnbrokers, strollers, fat landladies, sailors,Bawds, bailies, jilts, jockies, thieves, tumblers and tailors.

G. A. Stevens, Sports of the City jubileeThe story persists that Kean, rehearsing or performing a tumbling trick, fractured a leg so badly that it never fully mended. Versatility was an asset among strollers, and Kean would later credit Richardson with giving him his first acting opportunity in a major part, that of Young Norval in John Home's Douglas. More consistently, though, he tumbled and danced, developing the talents that would make him an outstanding Harlequin on provincial circuits.

Kean's first ‘adult’ engagement, no longer as ‘Master Carey’, was with Samuel Jerrold's company at Sheerness in spring 1804. He was ambitious to play leading roles in tragedy, but the taste of the time was against him. The model tragedian was the tall and stately John Philip Kemble. Kean was volatile, even fidgety, and less than 5 feet 7 inchestall. He had penetrating, dark eyes—many people remembered them as black—and dark hair. Until alcohol lamed and bloated him, he was light on his feet and thin-faced. Above all, there was a fierceness bordering on malevolence about the way he presented himself on stage and, all too often, off it. Jerrold gave him secondary roles. After a year Kean had had enough. He returned to London and further disappointment. He was reduced to playing in a fit-up theatre in Wivell's Billiard Room, Camden Town. A Belfast engagement in the summer of 1805 led nowhere, though it enabled him, from a secondary position, to observe the acting of Sarah Siddons. Perhaps because his determination to make something memorable of even a minor role marked him out, Kean drew the unfavourable notice of Mrs Siddons. He would later claim that she patted him on the head after a performance, saying, 'You have played very well, sir, very well. It's a pity, but there's too little of you to do any thing' (Cornwall, 3rd edn, 59). Mrs Siddons could certainly be cutting. At the height of Bettymania, she referred to Betty as 'the baby with a woman's name' (R. Manvell, Sarah Siddons, 1970, 284). More surprisingly, but no less typically, Kean, in the depths of his provincial doldrums, refused to act with Betty.

That outburst of professional pique occurred in Stroud in 1808. There would be much more reprehensible refusals to brook rivalry during Kean's years of fame. The years between Belfast and Stroud were inglorious. In minor roles at the Haymarket in 1806 he was scarcely noticed, and, after a spell with Sarah Baker's company on the Canterbury circuit, he rejoined Samuel Jerrold in September 1807. There was little kudos to be gained from acting in Sheerness, but it gave Kean a brief first chance in leading roles. Amid rumours that he had offended a local dignitary, Kean found his Sheerness engagement suddenly terminated. He was liable, throughout his life, to express his fear of neglect through attacks on those in authority. The significant outcome this time was a relegation to secondary roles in William Beverley's company on the Gloucester circuit. Another new member of the company, Columbine to Kean's Harlequin in Harlequin Mother Goose, was an Irishwoman eight years his senior. Mary Chambers (1779–1849)had left Waterford for Cheltenham with the intention of working as a governess. Acting was a stage-struck afterthought. She was temperamentally unsuited to the morally lax world of the theatre, but she was under its spell in the spring of 1808. In the long run regrettably, she was also under the spell of the wildly ambitious and sexually charismatic Kean. They were married in Stroud on 17 July 1808. On her side at least, it was a love match. Kean, beguiled by Mary's gentility, may have hoped for a substantial dowry, or, frustrated by her modesty, may have seen its only antidote in marriage. The aftermath was greater hardship than either had ever known.

Their first move was from the Gloucester circuit to Cheltenham, whose manager, John Boles Watson, had a theatrical empire stretching from Wales to Leicester. Kean was allowed his share of leading roles until the company reached the important theatre town of Birmingham, where he responded to his relegation to secondary parts by getting drunk—repeatedly. It was probably in Birmingham, and perversely linked to his married state, that a pattern of prolonged drinking bouts was established. These ‘benders’ lasted anything from three days to a week. The immediate result in Birmingham was debt. When, in June 1809, the Keans were offered an engagement with Andrew Cherry's company in Swansea, they had to leave Birmingham secretly and walk the 180 miles to Swansea. If Mary, six months pregnant, had dreamed of stability, she had ample time to reflect on her choice of husband. Their first son was born on 13 September 1809 and christened Howard, the family name of the dukes of Norfolk.

Trying to curb his impulsiveness in view of his new responsibilities, Kean remained with Cherry for two years. The company toured Ireland as well as Wales, and it was in or near Mary's home town of Waterford that their second son, Charles John Kean, was born on 18 January 1811. It was, after all, Charles Howard whom Kean liked to claim as his father. Also in Waterford, Kean's swordsmanship as Hamlet excited the admiration of Thomas Colley Grattan, stationed there as a subaltern. Grattan was the most loyal of the many men of distinction who befriended Kean over the years. Kean was sorely in need of friends in the months that followed his rash decision to leave Cherry's companywhen his demand for an increased salary was denied. The Keans arrived in England jobless and made a poverty-stricken tour of Scotland and the north of England, during which they were sometimes reduced to begging. It was a relief when, in January 1812, Richard Hughes engaged Kean to play leading roles on the Exeter circuit. His pride was both restored by the chance to act Macbeth, Richard III, Hamlet, and Othello, and dented by the greater demand for his Harlequin. Kean's now habitual dissipation was both symptom and cause of the failure of his marriage. His letters to London managers made no impression, and his behaviour became almost predictably irrational. Never at ease in comedy, he acted carelessly opposite Dorothy Jordan when the great comic actress joined the company for its Weymouth season in October 1812, and in Guernsey the following April he was so consistently drunk that the audience turned against him. Knowing that the money he earned should go towards supporting his sickly wife and sons, he spent it on prostitutes and drink. Self-belief vied with self-hatred to produce his explosive versions of both Richard III and Edmund Kean.

It was the chance attendance of Dr Joseph Drury, retired headmaster of Harrow School, at a playhouse in Teignmouth that initiated the change in Kean's fortunes. Drurycommended the young provincial actor to the amateur gentlemen then in control of Drury Lane, with whom he had some influence. After a delay, during which the Keans'elder son sickened with the after-effects of measles, the Drury Lane gentlemen dispatched their acting manager, Samuel Arnold, to Dorchester, where he watched Kean as Octavian in Richard Cumberland's The Mountaineers on 15 November 1813. Octavian, monumentally dignified in adversity, was in John Kemble's repertory and certainly not a gift for the demonic Kean. But Arnold, knowing the desperate financial state of Drury Lane in 1813, was sufficiently impressed to make Kean an offer, and even to allow him the choice of part for his début at England's premier theatre. It was unfortunate that the offer came just after the impecunious Kean had accepted a less attractive one from Robert William Elliston, new lessee of London's Olympic Theatre. While Kean haggled to extricate himself from the Olympic contract, Howard'scondition worsened. He died on 22 November 1813, a month after his fourth birthday. Penniless and distraught, Kean arrived in London early in December 1813 with the dispute between Elliston and Drury Lane unresolved. It seemed to him a choice between Harlequin at the Olympic and Shakespeare at Drury Lane.

Triumph at Drury Lane

In the new year of 1814 Kean languished, unpaid and fearful, until an agreement was reached between Arnold and Elliston. It involved a reduction from £8 to £6 in his promised salary, with the £2 going towards compensating Elliston. It was not until 26 January 1814 that Kean made his legendary début as Shylock, thereby recovering at a stroke the sinking fortunes of Drury Lane. In a famous retrospect, written over two years later, William Hazlitt recorded the impact: 'We wish we had never seen Mr. Kean. He has destroyed the Kemble religion and it is the religion in which we were brought up' (The Examiner, 27 Oct 1816). Hazlitt's perception that, in taking on Shylock, Keanwas also taking on John Kemble, is informative. Even in adversity, Kean was naturally adversarial. Acting for himself, he was also acting against a society that had scorned him. Inner fury, amounting frequently to paranoia, fuelled his finest performances and made them dangerous to a degree unrivalled on the English stage. He found points of identity with Shylock, and it was at these points that his intensity thrilled regency audiences. 'The character never stands still', wrote Hazlitt after the second night on 1 February 1814. 'There is no vacant pause in the action; the eye is never silent' (Morning Chronicle, 2 Feb 1814). For the critics close up in the pit, Kean's eyes were always a dominating feature, but he was a people's actor too, celebrated in the upper gallery as Kemble rarely was. His voice, reputedly weak in the upper register, resonated in the vastness of Drury Lane. He would continue to abuse it. In later years, it would crack under the strain, forcing him to hold back for most of a performance to preserve the energy for its peaks. The famous transitions from the rhetoric of high passion to the startlingly conversational may have owed as much to necessity as to art. He was envious of the vocal richness of Kemble's heir, Charles Mayne Young. Sober, he acknowledged the quality of Young's musical voice; drunk, as he generally was by 1823, he would rant to James Winston about having to act with 'that bloody thundering bugger'.

Drury Lane was sparsely patronized for Kean's first performance, but full for his second and for almost all the sixty-eight nights he played before the season ended in July 1814. On 12 February 1814 he gave his first London performance of Richard III, the part that best accommodated his genius. G. H. Lewes's memory held a boyhood image of the exquisite grace with which Kean would lean against the side scene while Anne railed at him: 'It was thoroughly feline—terrible yet beautiful' (Lewes, 10). If his Shylock was, in Douglas Jerrold's eyes, like a chapter of Genesis, his Richard was Mephistophelean. It can be partially recovered in the detailed record of his movements and vocal inflections made a decade later by the American actor James Hackett. Lord Byron compared Keanwith his own corsair:

There was a laughing devil in his sneer,That raised emotions of both rage and fear;And where his frown of hatred darkly fell,Hope withering fled, and Mercy sigh'd farewell!

Byron, The Corsair, 11. 223–6There is more than coincidence in the contemporaneous vogues for Kean and Byron's heroes. On 5 May 1814 Kean, one of the few actors to have overwhelmed his Iagos, played Othello. Surprisingly perhaps, he preferred it to Iago, which he played two days later, and would intermittently perform throughout his career. Othello's singularity among complacent Venetians, like Shylock's, activated Kean's own sense of isolation. He had the capacity, as well as the need, to make distinctive any character he impersonated, but his intuitive reading of the texts proposed to him enabled him to select parts that met him half-way. Luke, in Sir James Bland Burges's adaptation of Massinger's The City Madam, fitted the mould; it was the last new role in his triumphant first season at Drury Lane. He was doubtful only about his Hamlet, first performed on 12 March 1814, despite critical acclaim. He knew he was not at his best when required to burn slowly, and Hamlet, though a compulsory part of a tragic actor's repertory, was never his favourite.

Kean became the victim of his success, as he had been the victim of his failures. Welcomed in society, he often made a fool of himself, not least by his misguided sprinkling into conversation of half-understood Latin and Greek tags. His wife relished polite company, and for a while Kean indulged her with dinner parties. His salary was increased to £20 per week in March 1814, and in the provincial tour that followed he commanded £50 per night. There were gifts from admirers and a benefit that brought him over £1000. In October 1815 he leased a large house in Clarges Street, Piccadilly. Although some neighbours took offence at an upstart actor's presumptuousness in moving to a fashionable area, Mary had a fine setting for her dinner parties. Kean had completed a second season at Drury Lane, adding to his previous parts Macbeth (5 November 1814), Romeo (2 January 1815), and Richard II (9 March 1815). He was a competent Macbeth, too energetic as Richard, and ineffective as Romeo. His enemies were ready with unfavourable comparisons. Eliza O'Neill's Juliet at Covent Garden was the talk of the town. Kean's Drury Lane Romeo lacked her appealing innocence. The burden of being the theatre's only effective draw was heavy, and Romeo was one of several dubious choices during this second season. Thomas Morton's Town and Country, in which Kean played Reuben Glenroy, is a dull play, and Cumberland's The Wheel of Fortune, even with Kean as Penruddock, a gloomy one. Mrs Wilmot's Ina lasted only one night, with Kean in the main part. The committee's control of the repertory was dangerously biased. Outside Shakespeare, Kean's best opportunities came in the vengeful role of Zanga in Edward Young's The Revenge and as Abel Drugger in The Tobacconist, an afterpiece carved out of Ben Jonson's The Alchemist. This latter role gave rise to an unresolved debate about Kean's quality in comedy. He would have liked to emulate Garrick's versatility, but Lewes is probably right that 'he had no playfulness that was not as the playfulness of a panther, showing her claws every moment' (Lewes, 10).

The move to respectability in Clarges Street concealed a counter-move to depravity in the streets around Covent Garden. In summer 1815 Kean founded the Wolves Club, a drinking society largely composed of theatrical professionals dedicated to debauchery. Rightly or wrongly, its members were regularly accused of forming a claque in support of Kean or against any actor who threatened his supremacy. They bolstered Kean'semerging megalomania. The major creation of his third season was Sir Giles Overreach in Massinger's A New Way to Pay Old Debts. Overreach was, with the arguable exception of King Lear, the last of Kean's great parts. Byron was not the only person to be convulsed by his mad ravings in the final act. For Hazlitt, Kean's faultless playing of the role simply confirmed his greatness. But on 26 March 1816, when he should have been performing Sforza in Massinger's The Duke of Milan, Kean was drunk in a Deptford tavern. It was his first betrayal of the Drury Lane audience. By 9 May, when he created the title role in Charles Maturin's Bertram, he had been forgiven. Bertram was his second successful new role of the 1815–16 season. Kean had been unimpressed by the play at first reading, but he cut and rewrote it to make his own role paramount. Maturinwas not consulted. Few living writers had the status to challenge the judgement of a leading actor.

Early in his fourth season, on 28 October 1816, Kean played Shakespeare's Timon. The performance was admired, but houses were moderate. Drury Lane was losing the contest with its perennial rival, Covent Garden. William Charles Macready made his début at Covent Garden on 16 September 1816, audiences crowded to see Kemble there in his farewell season, and, on 12 February 1817, the young Junius Brutus Booth made his well-publicized first appearance in London. Booth had openly modelled himself on Kean, who found the imitation disconcerting. When Booth quarrelled with the Covent Garden management, Kean plotted to have him contracted to Drury Lane, where, on 20 February 1817, Kean as Othello obliterated Booth's Iago. The mortified Booth returned to Covent Garden, soon to emigrate to America where he founded a famous theatrical dynasty. It was not the last time Kean set about destroying a rival, and the retirement of Kemble on 23 June 1817 left him unchallenged as king of tragedy.

The middle years

Kean was thirty in 1817, and discerning critics feared that he was already past his prime. Drink-sodden and suffering from venereal disease, he lived like a cautionary tale on the perils of fame. He employed a private secretary, ran a fleet of Thames wherries, and paraded his pet lion in London's streets. His income, unprecedented for an actor, was matched by his expenditure, and he no longer bothered to conceal his philandering. The number of missed performances increased and, although reliable in his old parts, he found new ones difficult to master. The four false starts in the 1817–18 season included Barabas in Marlowe's The Jew of Malta (24 April 1818) and Shakespeare's King John (1 June 1818). Kean was now claiming the right to veto new plays. If overruled, he could always destroy them with a lacklustre performance, as he did Jane Porter's Switzerlandon 15 February 1819. The probable truth is that, for the first time, he was experiencing the actor's overwhelming fear of failure. Kean was temperamentally bound to camouflage fear with bluster, as he did notoriously in the case of Charles Bucke's The Italians. This play was submitted to Drury Lane in November 1817, when Kean endorsed the committee's recommendation that it be staged. But Kean had second thoughts about his intended role as Albanio. The delaying tactics he employed were, at best, undignified, and Bucke's patience wore out. Early in 1819 he published the play with a tell-tale preface on the conduct of Drury Lane, concluding that, 'though Mr. Kean is saving that establishment with his right hand, he is ruining it with his left'. In the ensuing pamphlet debate, public opinion was predominantly on Bucke's side. The Drury Lane audience forced from Kean a perfunctory apology that satisfied no one.

The dispute was the last straw for Drury Lane's amateur committee. In summer 1819 they put the theatre up for rent, and Kean was one of the bidders. To his chagrin he was outbid by Elliston. To make things worse, Elliston held him to his contract, thus postponing plans for a lucrative visit to America. Kean made his first appearance under Elliston, in this his seventh season at Drury Lane, on 8 November 1819. His choice of Richard III was given a new piquancy by the fact that Covent Garden's new star, Macready, was currently playing it there. The rivalry served both theatres, but Keanmade the mistake of extending it by tackling Coriolanus, in which Macready had recently made an impression, on 25 January 1820. Kemble had specialized in muscular Roman roles. They fitted Kean no better than the cerebral Hamlet or even Romeo. Much more notable was his London début, on 24 April 1820, as King Lear. The version was Nahum Tate's, and Kean's performance, as dictated by his stamina, was one of fits and starts. But the vivid transitions were there, together with the hair-raising pathos. Audiences rallied to him for his pre-American farewell performances in the summer of 1820. The contradictory relationship with Elliston continued. They were drinking and whoring companions at the same time as they were professional contenders. The diary of Elliston's waspish acting manager, James Winston, records their debauchery with suspicious relish. If Winston is to be trusted, Kean would copulate with actresses or prostitutes before and after a play, and during its intervals as well. Such excess is more than mere self-indulgence. Kean's first visit to America was an image of his flight from himself. In the spring of 1820 he had begun what was to be a fateful affair with Charlotte Cox, with the apparent collusion of her eminently respectable husband, a London alderman and member of Drury Lane's general committee. This was the most obsessed and obsessive relationship Kean ever had. It would reach a savage conclusion in 1825. Meanwhile, during his last week in London, two paternity suits were brought against him. He set sail from Liverpool on 7 October 1820 and, on 29 November, opened as Richard III at the Anthony Street Theatre, New York.

Kean was the first major English actor to tour America since George Frederick Cooke in 1810. His behaviour was exemplary and his reception enthusiastic. Able to select only his favourite parts and unthreatened by competition, he was more stable than he had ever been. From December to May, in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Baltimore, he scarcely put a foot wrong. But then, ignoring advice, he resolved on a return visit to Boston. Bostonians did not attend the theatre in summer. Kean opened to a poor house on 23 May 1821, and when even fewer were present at curtain-up on 25 May he declined to perform. Press reaction converted a tantrum into an international insult. Warned that his appearance in any American theatre would precipitate a riot, Kean embarked for England on 7 June 1821. Having made £6000 in six months, he would have liked to stay longer.

Led back to Drury Lane at the head of a triumphal procession cannily staged by Elliston, Kean opened as Richard III on 23 July 1821. Before the end of the week he had also played Shylock and Othello. There followed a break until November. Charlotte Cox was uppermost in his mind. Her once prosperous husband had toppled into bankruptcy, and she was pressing Kean to leave his wife. Kean found himself in the unusual position of advising caution. Despite the warmth of his initial welcome, the fickle audience was disappointed by him. His eighth season at Drury Lane was a financial and artistic failure. None of his new characters, which included Wolsey in Henry VIII (20 May 1822), held the stage, and the season brought Elliston to the brink of ruin. As usual, Kean ran away, this time to the Isle of Bute, where, in October 1822, he acquired a house and 20 acres. It was there that he heard of Elliston's emergency plan to enliven the 1822–3 season by pitting three dissatisfied Covent Garden stars against three of his Drury Lane regulars. Kean's opposition was to be the dignified tragedian, Charles Mayne Young. Resentful and anxious, Kean skulked in Scotland until November 1822. To public delight, he then engaged with Young in Othello on 27 November, and once the press had awarded him a narrow victory entered into more confident battle in Venice Preserv'd(Jaffeir to Young's Pierre) and Cymbeline (Posthumus to Young's Iachimo). Despite the inflated salaries he was paying, Elliston had recovered some ground by the end of the season. Kean and his manager, though, were at loggerheads over the future. Kean'scontract had a year to run, and he was desperate to establish a position of strength from which to negotiate. But Elliston was notoriously slippery, and matters were unresolved in the summer of 1823. The affair with Charlotte Cox was unresolved too, and the strain was telling on Kean. He was shocked to hear of Elliston's decision to engage Macready for the coming season. It was one thing to take on an ageing star like Young, another to confront a rising star. Kean remained in his Scottish retreat until Macready's initial run was over, and there was little of note in his four months of performance from December 1823 to April 1824. For the first time at Drury Lane, he was almost unobtrusive.

Trial and decline

Kean's affair with Charlotte Cox finally exploded in mutual recrimination early in 1824. Almost at once Charlotte left home to live with her husband's clerk. In her abandoned bedroom, tied together by a ribbon, were the letters Kean had written to her. They would furnish the incriminating evidence at the trial a year later. On 9 April 1824 Coxtook out a writ against Kean for criminal conversation with his wife. Kean's apparent unconcern may have been a pretence. Once his Drury Lane commitments were over, he ran away, initially to Brighton and then, with his wife, to France. He was making a sad attempt to keep his family together. He had arranged for Charles to go to Eton College in June, with an annual allowance of £300. It would not be easy for an actor's son to survive at Eton, even though his father had a house in Clarges Street and an estate in Scotland. In July 1824 Kean signed a new contract with Elliston. He was to receive an unprecedented £50 per night for twenty-three performances in the new year.

The case of Cox <i>v.</i> Kean was heard on 17 January 1825 in an atmosphere of prurient public interest. The court found for the plaintiff, awarding him damages of £800. Neither marriage survived the trial. Acceding to her wish to separate, Keansettled on Mary £504 per year, out of which she was to pay for Charles's education. The allowance of £50 per year, which he had been paying to his importunate mother since his first success in 1814, continued until his death. It was an act of bravado, in the fraught atmosphere following the trial, for Kean to return to Drury Lane on 24 January 1825. His Richard III, though played right through, was drowned out by conflicting voices in the auditorium. The same was true of Othello on 28 January. The Times led a press campaign against 'that obscene little personage' (28 Jan 1825), castigating this 'obscene mimic' (29 Jan 1825) for his failure to abase himself before the audience. After playing Sir Giles Overreach in front of a clamorous audience on 31 January, Keanclaimed in a curtain speech to have 'made as much concession to an English audience as an English actor ought' (Hawkins, 2.243). For the remaining twenty nights of his engagement, he was generally allowed to perform without significant interruption, but there was uproar again at most of the venues on his subsequent provincial tour. In the long run, this hostility destroyed him. After the Cox trial, Kean was rarely again a great actor and never a self-sufficient man.

When Kean sailed for America in September 1825, it was with the hope of escaping to make a new home there; but he opened to the now familiar pandemonium at the Park Theatre, New York, on 14 November 1825. There was a generous response to the statement he then published in the National Advocate, and the rest of his New York performances passed off peacefully. Albany audiences were also tolerant, but in Boston on 19 December 1825 Kean was driven from the stage and there was a serious riot. Much shaken, Kean continued his tour for a further year, ranging from Charleston in the south to Montreal, where he was rapturously received by Canadian audiences, for whom an English star was a rarity. His decision to return to England may have been the result of a cruel deception. Kean was given to understand that the owners of Drury Lane wished him to succeed the bankrupt Elliston as lessee. He sailed for England on 6 December 1826, not knowing that the lesseeship had already been purchased by the American Stephen Price.

The American tour had restored Kean's fortunes and improved his health, but it had stretched him to the limit. Bitter about the lesseeship of Drury Lane, he took rooms in Hummums Hotel, near Covent Garden, and resumed his dissipated habits. The chronic gastritis and gallstones discovered at his autopsy began at this time to affect him, and his leg was often too painful to bear his weight; Raymund FitzSimons questions the contemporary diagnosis of gout, suspecting that a syphilitic lesion was a likelier cause. The slow poison of mercury treatment may have contributed to his inability to memorize new parts and his increasing difficulty in sustaining familiar ones. His fumbling forgetfulness on the night of 21 May 1827 turned into an embarrassing fiasco the production of his friend Colley Grattan's Ben Nazir. The remorseful Kean began to talk of retirement, but he had one resentful trick to play first. Because Stephen Pricehad refused him a share in Drury Lane, Kean elected to play his farewell season at Covent Garden. Price countered by announcing as his new star Kean's son Charles. Father and son had made some attempts at reconciliation, though Charles had taken his mother's side in the separation and defied his father by turning actor. The prospect of rivalry threatened their tenuous alliance, and it was probably fortunate that Charlesinherited so little of Edmund's charisma. Price's ruse proved ineffective.

Though needing to nurse his health, Kean was more effective at Covent Garden than he had been of late at Drury Lane. His private life, though, was in disarray. He was living with a formidable Irish prostitute called Ophelia Benjamin, whom he feared and needed. In the early summer of 1828 he was fit enough to fulfil an engagement in Paris, but his reception was lukewarm and he retreated to his Scottish property, returning refreshed to Covent Garden in October 1828. In January 1829 his health collapsed and he had to take three months' rest. A tour of Irish theatres with his son had to be abandoned in Cork in April 1829, when he collapsed again. It was restarted a month later, and again interrupted for reasons of Kean's health. After recuperating in Scotland, he returned to London, only to quarrel with Charles Kemble, the manager of Covent Garden. From December 1829 to March 1830 Kean was back at Drury Lane, where he found his reception encouraging. Foolishly, he attempted another new part, Shakespeare's Henry V, but at its opening on 8 March 1830 his memory failed again. In despair, he announced his retirement for a second time and played a second round of farewells in the summer of 1830. The problem was that he could not afford to retire so early. He had squandered money, not least in fits of drunken generosity, so that, too ill to make the intended trip to America, he was forced to return to Drury Lane in January 1831. The newspapers mocked him in anticipation of a third retirement.

In the spring of 1831 Kean made his final bid for independence when he leased the King's Theatre in Richmond, Surrey, setting up home in the adjacent cottage. When strong enough, he acted there as well as at the Haymarket. He was living now under the care of the seventy-year-old Charlotte Tidswell, who had driven Ophelia Benjaminaway. Illness had so tamed Kean that he agreed to play opposite Macready at Drury Lane during the 1832–3 season. Honours were even when they appeared in Othello on 26 November 1832, and they repeated it intermittently until Kean's health failed again. Captain Polhill, Drury Lane's new lessee, refused the ailing actor a loan in the new year of 1833. Kean took the only revenge available to him by crossing to Covent Garden to play Othello opposite his son's Iago. The performance on 25 March 1833 was his last. Unable to complete it, he was carried back to Richmond, where, after languishing for several weeks, he died on 15 May 1833. An application to bury him next to Garrick in Westminster Abbey was denied, and on 25 May he was buried at the Old Church in Richmond. Six years later Charles Kean had a memorial tablet placed in the church. Long before then Kean's widow, with whom he had been reconciled shortly before his death, had sold most of his possessions at auction to pay off his debts.

Kean's repertory of great roles was small and his range narrow, but he remains the English theatre's supreme example of the charismatic actor. Three years after his death, Alexandre Dumas père chose him as the subject of a play, Kean (later reworked by Jean-Paul Sartre), seeing in Kean an embodiment of the rebellious spirit of Romanticism. The image has been historically persuasive.

John Sartain was born in London, England. He learned line engraving, and produced several of the plates in William Young Ottley's Early Florentine School (1826). In 1828, he began to make mezzotints. He studied painting under John Varley and Henry James Richter.

In 1830, at the age of 22, he emigrated to the United States and settled in Philadelphia. There he studied with Joshua Shaw and Manuel J. de Franca. For about ten years after his arrival in the United States, he painted portraits in oil and miniatures on ivory. During the same time, he found employment in making designs for banknote vignettes, and also in drawing on wood for book illustrations. He was a 33 degree Mason. He pioneered mezzotint engraving in the United States. He engraved plates in 1841–48 for Graham's Magazine, published by George Rex Graham, and believed his work was responsible for the publication's sudden success.[2] Sartain became editor and proprietor of Campbell's Foreign Semi-Monthly Magazine in 1843. He had an interest at the same time in the Eclectic Museum, for which, later, when John H. Agnew was alone in charge, he simply engraved the plates.

-

Pennsylvania Hall burning, 1838. Sartain was an eyewitness.

-

John Sartain, Mary, Queen of Scots, The Evening Before Her Execution

-

John Sartain, Zachary Taylor

Sartain's Magazine

In 1848, he purchased a half interest in the Union Magazine, a New York-based periodical. He transferred it to Philadelphia, where it was renamed Sartain's Union Magazine, and from 1849 to 1852 he published it with Graham. It became very well known during those four years.

During this time, besides his editorial work and the engravings that had to be made regularly for the periodicals with which he was connected, Sartain produced an enormous quantity of plates for book-illustration.

-

John Sartain

-

John Sartain, Edgar Allan Poe

Sartain was a colleague and friend of Edgar Allan Poe. Around July 2, 1849, about four months before Poe's death, the author unexpectedly visited Sartain's house in Philadelphia. Looking "pale and haggard" with "a wild and frightened expression in his eyes", Poe told Sartain that he was being pursued and needed protection; Poe asked for a razor so that he could shave off his mustache to become less recognizable. Sartain offered to cut it off himself using scissors. Poe had said he had overheard people while on the train who were conspiring to murder him. Sartain asked why anyone would want to kill him, Poe answered it was "a woman trouble". However, later when Sartain let Poe stay the night with him at his house, Poe informed him that he may have been hallucinating. This incident was four months before Poe's death. Poe gave Sartain a new poem, The Bells, which was published in Sartain's Union Magazine in November 1849, a month after Poe's death.Sartain's also published the first authorized printing of Annabel Lee, also posthumously.

Years in Philadelphia

After his arrival in Philadelphia, Sartain took an active interest in art matters there. He held various offices in the Artists' Fund Society, the School of Design for Women, and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and was actively connected with other educational institutions in the city. He had visited Europe several times, and on the occasion of his second visit in 1862 he was elected a member of the society "Artis et Amicitiæ" in Amsterdam.

Sartain had charge of the art department of the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, in 1876. In recognition of his services there, the king of Italy conferred on him the title of cavaliere of the Order of the Crown of Italy. His architectural knowledge was frequently requisitioned: he took a prominent part in the work of the committee on the Washington Memorial by Rudolf Siemering in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, and he designed medallions for the monument to George Washington and Lafayette erected in 1869 in Monument Cemetery, Philadelphia. His Reminiscences of a Very Old Man (New York, 1899) are of unusual interest.

-

John Sartain, William Henry Harrison

-

John Sartain, Alexander Pope

-

John Sartain, Cinque (The Amistad Case)

Sartain was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1897. Upon his death later that year, the 89-year-old Sartain was buried in Monument Cemetery. Shortly before his death, The Philadelphia School of Design for Women created the John Sartain Fellowship in recognition of his 28 year tenure as Director.

In 1956 the cemetery was condemned by the city and given to Temple University which cleared it for a parking lot. Sartain's body was not claimed and he and approximately 20,000 other unclaimed bodies were re-interred in a large mass grave at Lawnview Cemetery. The tombstones, including the cemetery's 70 feet high central monument to George Washington and General Lafayette and his family monument (all designed by Sartain) were dumped into the Delaware River to serve as the foundations for the Betsy Ross Bridge.

Family

John Sartain married Susannah Longmate Swaine and they had eight children. Samuel (1830-1906), who was an engraver; Henry (1833-1895); William (1843-1925); and Emily Sartain pursued careers as artists. Emily Sartain first practised art as an engraver under her father. She studied at the Pennsylvania Academy under Christian Schussele, and then, until 1875, with Évariste Vital Luminais in Paris. In 1886, she became principal of the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. William Sartain engraved under his father's supervision until he was about 24. From 1867 to 1868, he studied under Christian Schussele and at the Pennsylvania Academy. He then went to Paris, where he studied with Léon Bonnat. In 1877, he returned to the United States, settling in New York, where he was elected an associate of the National Academy of Design in 1880. He was one of the founders of the Society of American Artists. He painted both landscape and figure subjects.

-

Emily Sartain, 1876 plate

-

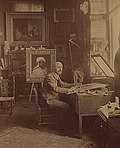

William Sartain in his studio, circa 1900