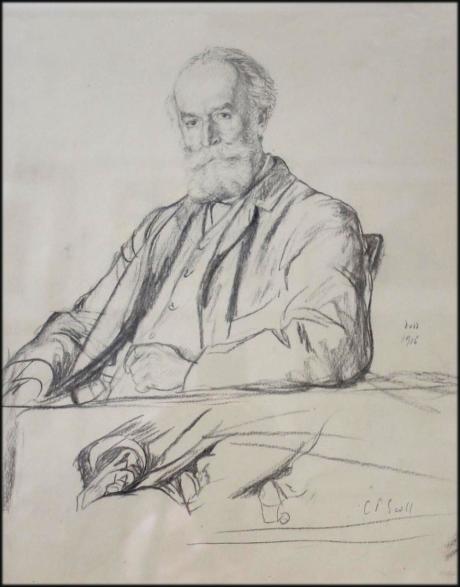

and dated "Dodd 1916"

working drawing for the oil on canvas portrait in the Manchester City Art Gallery Acsesion number : 1978.180 bequeathed by Mrs Alice Olga Scott, 1978

etching, 1916 NPG 3997

Charles Prestwich Scott, (1846–1932), newspaper editor and proprietor, was born at Bath on 26 October 1846. He was the eighth child and fourth son of Russell Scott (1801–1880), a partner in a coal company, and his wife, Isabella Civil, daughter of Joseph Prestwich, wine merchant. Scott's upbringing was Unitarian. He attended Hove School, Sussex, run by a Unitarian minister, and Clapham grammar school. He also, for reasons of health, spent a period with a private tutor on the Isle of Wight, the Revd Arthur Watson. Despite religious obstacles, in 1865 he secured admission to Corpus Christi, Oxford, immersing himself in a full university life—including rowing and debating—and graduating BA in 1869 with a first class in literae humaniores. Thereafter, he habitually looked to Oxford for recruits to his staff.

Scott's choice of career was determined by three things: family connections, his evident literary skills, and his strongly directed personality. J. E. Taylor, his cousin (but many years his senior), owned the Manchester Guardian, which Taylor's father had founded. An organ both of the flourishing cotton trade and of religious and political dissent, it was the most valuable newspaper property outside London. Taylor offered Scott a position on the paper which he took up in 1871, and elevated him to the editorship in January 1872. Scott, aged only twenty-five, was many years junior to the more experienced of his colleagues, but this did not prove a difficulty. His piercing brown eyes, striking good looks, newly acquired beard, and authoritative manner left no doubt who was in charge. Scott remained editor for fifty-seven years.

Within a short time Scott was attracting to the newspaper highly distinguished writers on the arts and sciences, including such figures as A. W. Ward, James Bryce, C. E. Montague, and Arnold Toynbee. In politics the Manchester Guardian in 1872 was more whig than radical. Scott, for more than a decade, seemed content with this. But perhaps he began foreshadowing a change in political direction by the attention his paper began devoting to social questions. The Guardian carried well-documented accounts of conditions in the mining districts of northern England, of the indifferent housing of the poor, and of deficiencies in the medical services. Scott sent W. T. Arnold (grandson of Arnold of Rugby, and nephew of Matthew) to Ireland, from whence came reports of appalling social conditions and their connection with political discontents and political crime.

Hence the ground was not unprepared when, in 1886, W. E. Gladstone committed his party to Irish home rule (thereby splitting the Liberal Party). Scott embraced the cause. It proved a wide-ranging conversion, from which Scott emerged not just a home-ruler but a social radical. His newspaper in the next three decades opposed British imperialism in South Africa (and in particular Cecil Rhodes's exploitation of native labour), resisted large programmes of armaments, and gave devoted support to women's suffrage and the many schemes for social improvement embodied in what, with the Liberals restored to office from 1905, became the ‘new Liberalism’.

In 1895, while remaining editor of the Manchester Guardian, Scott entered parliament for the Leigh division of Lancashire as a Liberal. He remained until 1905. It proved a stormy decade. The South African War not only divided the Liberals (again) but cost the Manchester Guardian readers and advertisers on account of its ‘unpatriotic’ attitude. What Scott particularly derived from his spell in parliament was personal attachments and antipathies. He never forgave H. H. Asquith his ‘imperialist’ position during the South African War, nor forgot Lloyd George's courage in taking a stand for the ‘pro-Boer’ line.

In 1905, following Taylor's death, Scott became proprietor as well as editor of the Manchester Guardian. Taylor's will left the fate of the paper unclear, and Scott had to raise £240,000 to secure it. It was not a reckless investment. Certainly, the Guardian's brand of responsible journalism could never capture the mass market conjured forth by Northcliffe, and it was already threatened by encroachment from the metropolis. But it rested on a powerful provincial base, and appealed well beyond Lancashire as the one quality newspaper espousing the radical cause.

With the Liberals in power from 1905, Scott found important figures eager to consult him and secure his good opinion. He travelled often to London to talk with them, and from 1911 occupied the return journey recording what had transpired. Unwittingly, he thereby compiled a body of documents providing penetrating insights into the contemporary thinking of men such as Lloyd George and Winston Churchill. Plainly they respected his opinion, even if they did not always act on it.

With the outbreak of war in 1914 Scott confronted painful and ambiguous issues. Hitherto influenced by the myopic R. T. Reid, Lord Loreburn (also an ally from his days in parliament), he had tended to discount the threat from Germany and to locate international troubles in the diplomatic system. But once Britain was committed to war, Scott took a determined line. The struggle, he judged, must be conducted with determination. Certainly, during 1915 and 1916 he argued against conscription, and deplored the ferocious suppression of the Easter rising in Dublin. But he did not doubt that the nation must dispense with Asquith's rather aloof leadership and accept the passionate commitment to the struggle of Lloyd George—even at the head of a mainly Conservative government.

Some of Lloyd George's actions after 1916, such as the enactment of female suffrage (1918) and the espousal of the cause of a Jewish national home in Palestine, gave Scott great satisfaction. (He had contributed directly to the latter outcome by introducing Chaim Weizmann, both Zionist and munitions chemist, to Lloyd George in 1915.) But Scott loathed other aspects of Lloyd George's wartime and post-war governments: military intervention against the Bolsheviks in Russia, the malevolent jingoism of the 1918 election campaign, and uncontrolled military repression in Ireland. On this last matter, for a year (1920–21) Scott severed relations with Lloyd George.

The post-war world was not a hopeful place for Scott. The decline of cotton threatened Manchester and its great newspaper. Hopes for the League of Nations dwindled when the United States rejected Woodrow Wilson. The Liberal Party was split again, and the rivalry of Labour towards it, with consequent dispersal of the anti-Conservative vote, ensured a succession of tory governments. During the 1920s Scott once more pinned his hopes on Lloyd George, and welcomed Labour's (brief) accessions to office. But neither cause prospered. Concerning his newspaper, he encouraged useful initiatives, such as film and radio reviews and the introduction of the Manchester Guardian Commercial. But by the time he resigned his editorship in 1929, he had somewhat outlived his usefulness.

During his lifetime, Scott was not without his critics. He could be stingy in remunerating valuable colleagues, and at close quarters he might seem authoritarian rather than noble-minded. Yet he was entitled to the high stature he acquired during his lifetime and has since retained. For, as another prominent editor put it, the Manchester Guardian became under him ‘a newspaper with which the whole world had to reckon’ (Hammond, 59).

On 20 May 1874 Scott married Rachel Susan Cook, daughter of the professor of ecclesiastical history at St Andrews University [see Scott, Rachel Susan (1848–1905)]. She was one of the original undergraduates at what was to become Girton College, and she regularly reviewed novels for the Manchester Guardian until her premature death in November 1905. Of their four children (three boys and one girl), one became manager of the newspaper and another, Edward Taylor Scott, succeeded Scott as editor; a grandson, Laurence Prestwich Scott, was the third and final family member to edit the paper.

From 1882 until his death Scott lived at The Firs, Fallowfield, amid a large garden and noble trees. He took to making the journey to and from the Manchester Guardian offices by bicycle, involving travelling late at night, and he kept up the practice until beyond his eightieth birthday. His last recorded mishap (‘I have a useful knack of falling without hurting myself’) occurred less than a year before his death. In 1923 Scott was made an honorary fellow of his Oxford college, and in 1930 a freeman of the city of Manchester. He persistently declined offers of a peerage.

Scott died at The Firs on 1 January 1932. Manchester thereupon paid him a remarkable tribute: on a cold winter morning, huge numbers turned out to offer their last respects in what became an unofficial, unorchestrated, state funeral. Scott is best remembered for the dictum that the primary business of a newspaper is ‘the gathering of news’: ‘Comment is free, but facts are sacred’ (Manchester Guardian, 5 May 1921). Yet for him the real interest of a newspaper lay with the leading article, and with its power to mould and direct opinion. It was the elevated quality of the opinions he sought to propagate, and the measured way in which he advocated them, which gave his career in journalism its special distinction.

Trevor Wilson DNB

Francis Edgar Dodd, (1874–1949), painter and etcher, was born in Upper Park Street, Holyhead, Anglesey, on 29 November 1874, the third son of the Revd Benjamin Dodd, a Wesleyan Methodist minister who had once been a blacksmith, and his wife, Jane Frances, daughter of Jonathan Shaw, cotton broker, of Liverpool. After his family had moved to Glasgow, Dodd attended Garnett Hill School. There in 1889 he began to learn painting. There he also met his future brother-in-law and lifelong friend the painter and etcher Muirhead Bone. While he worked as a china decorator with Messrs MacDougal he began to study at the Glasgow School of Art, winning the Haldane travelling scholarship of £100 per annum, which he eked out for eighteen months, in 1893. He went to Aman-Jean's academy in Paris but on the advice of J. A. M. Whistler he spent some time in Venice, studying Tintoretto, and visited Florence, Milan, and Antwerp.

In 1895 Dodd settled with his family at Manchester. His circle of acquaintance included the newspaper editor C. P. Scott and the literary scholar Oliver Elton, whose portraits he etched in 1916. He was closely associated with the artist Susan Isabel Dacre (1844–1933), who posed for his painting Signora Lotto (1906), now in Manchester City Galleries. She was also the model for some of his first drypoints as in Looking at a Picture(1907). He had absorbed something of the Glasgow school's impressionism and something of the style of the painter Alfred Stevens. At Manchester he began to explore the possibilities of painting suburban scenes. Works in various media were exhibited by him in the Manchester Academy, and in 1898 Bernhard Sickert invited him to exhibit with the New English Art Club. He became an active member of both institutions; the latter owed much to his skilful handling of its finances.

In 1901 Dodd went on the first of three visits to Spain, and in 1904 he settled in London. His friends at this period included Charles March Gere, Henry Lamb, and Henry Rushbury; all four later became Royal Academicians. Dodd began to exhibit at the Royal Academy in 1923, and was elected an associate in 1927 and Royal Academician in 1935. He was also a member of the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours and of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters, and a trustee of the Tate Gallery (1929–35). As official artist to the Ministry of Information during the First World War, Dodd made portraits of British naval and military commanders, and was afterwards attached to the Admiralty to carry out drawings of submarines. These are now in the Imperial War Museum. Portraits by him are in the National Portrait Gallery, London, at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, and at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

It was in his portraits that Dodd excelled as an etcher, above all in those of his brother artists. Direct, relaxed, and highly competent, the portraits reveal him as a master of his craft. Dodd got off to a flying start producing thirty-six plates in 1907 and 1908, among them the forceful image of his fellow etcher, Bone at the Press. In 1909 Dodd executed the drypoint which Bone considered ‘a masterpiece’, of the young sculptor Jacob Epstein. In 1915 he made twenty-three plates, the most he ever produced in a year, including David Muirhead seated at his easel, and the Lancastrian architect Charles Holden. Charles Cundall, in his studio (1926), was another of his best subjects. He did only eighteen plates after 1929, but he produced a total of 210. He gave a complete collection of his prints to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford in 1948.

On 8 April 1911 Dodd married Mary Arabella (1871/2–1948), daughter of John Brouncker Ingle, a solicitor, of London. On 27 January 1949 he married, as his second wife, Ellen (Nell) Margaret (b. 1908/9), daughter of Charles Tanner, builder's assistant, of London. She had been his model for many years. There were no children by either marriage. Dodd gassed himself at his home at 51 Blackheath Park, Blackheath, Greenwich, and died on 7 March 1949. Examples of Dodd's work are in the Tate collection, the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Manchester City Galleries, and the Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow.

Brian Reade, rev. Ian Lowe DNB