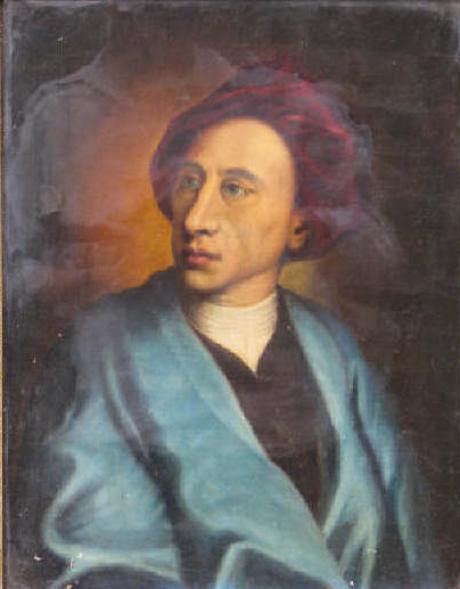

This portrait is based on the Portrait of Pope by William Hoare, currently in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 – 30 May 1744) is generally regarded as the greatest English poet of the eighteenth century, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third most frequently quoted writer in the English language, after Shakespeare and Tennyson.[2] Pope was a master of the heroic couplet.

Pope was born in the City of London to Alexander (senior, a linen merchant) and Edith Pope (née Turner), who were both Roman Catholic. Pope's education was affected by the laws in force at the time upholding the status of the established Church of England, which banned Catholics from teaching on pain of perpetual imprisonment. Pope was taught to read by his aunt and then sent to two surreptitious Catholic schools, at Twyford and at Hyde Park Corner. Catholic schools, while illegal, were tolerated in some areas.

From early childhood he suffered numerous health problems, including Pott's disease (a form of tuberculosis affecting the spine) which deformed his body and stunted his growth, no doubt helping to end his life at the relatively young age of 56. He never grew beyond 1.37 metres (4 feet 6 inches) tall. Although he never married, he had many women friends and wrote them witty letters.

In 1700, his family was forced to move to a small estate in Binfield, Berkshire due to strong anti-Catholic sentiment and a statute preventing Catholics from living within 10 miles (16 km) of either London or Westminster. Pope would later describe the countryside around the house in his poem Windsor Forest.

With his formal education now at an end, Pope embarked on an extensive campaign of reading. As he later remembered: "In a few years I had dipped into a great number of the English, French, Italian, Latin, and Greek poets. This I did without any design but that of pleasing myself, and got the languages by hunting after the stories...rather than read the books to get the languages." His very favourite author was Homer, whom he had first read aged eight in the English translation by John Ogilby. Pope was already writing verse: he claimed he wrote one poem, Ode to Solitude, at the age of twelve.

The death of Alexander Pope from Museus, a threnody by William Mason. Diana holds the dying Pope, and John Milton, Edmund Spenser, and Geoffrey Chaucer prepare to welcome him to heaven.The poetry of Alexander Pope holds an acknowledged place in the canon of English literature, although his work has gone in and out of fashion. One edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations includes no fewer than 212 quotations from Pope.

Some quotations from Pope's work have passed so deeply into the English language that they are often taken as proverbial by those who do not know their source: "A little learning is a dang'rous thing" (from the Essay on Criticism); "To err is human, to forgive, divine" (ibid.); "For fools rush in where angels fear to tread" (ibid); "Hope springs eternal in the human breast" and "The proper study of mankind is man" (Essay on Man). This would have greatly pleased Pope, who wrote:

True wit is nature to advantage dress’d; What oft was thought, but ne’er so well express’d. Pope dominated his age to an extent few writers before or since have matched. After his death, it was almost inevitable a reaction would set in against his poetry, especially with the first stirrings of Romanticism in the late eighteenth century.

In An Essay on the Genius and Writings of Pope (1756 and 1782), Joseph Warton denied Pope was a "true poet", merely a "man of wit" and a "man of sense". In his Lives of the Poets Doctor Johnson countered: "...It is surely superfluous to answer the question that has once been asked, whether Pope was a poet, otherwise than by asking in return, if Pope be not a poet, where is poetry to be found?". But he was fighting a losing battle against changing taste.

The Romantics had little time for Pope, with the notable exception of Lord Byron, who acclaimed him as “the great moral poet of all times, of all climes, of all feelings, and all stages of existence”. Keats dismissed the style of writers who wrote in heroic couplets, saying:

They sway'd about upon a rocking horse, And thought it Pegasus. (Sleep and Poetry) In the Victorian era, Matthew Arnold dismissed Pope and Dryden as "classics of our prose". The 19th century considered his diction artificial, his versification too regular, and his satires insufficiently humane. The third charge has been disputed by various 20th century critics including William Empson, and the first does not apply at all to his best work. That Pope was constrained by the demands of "acceptable" diction and prosody is undeniable, but the elegance and flexibility with which Pope used this technique shows that great poetry could be written with these constraints. His expression is concise and forceful, conveying emotion as well as reason and wit.

In his time Pope was famous for his witty satires and aggressive, bitter quarrels with other writers. When his edition of William Shakespeare was attacked, he answered with the savage burlesque The Dunciad (1728), which was widened in 1742. It ridiculed bad writers, scientists, and critics: "While pensive poets painful vigils keep, / Sleepless themselves to give their readers sleep." With the growth of Romanticism Pope's poetry was increasingly seen as outdated and the 'Age of Pope' ended. It was not until the 1930s that any serious attempts were made to rediscover the poet's work.