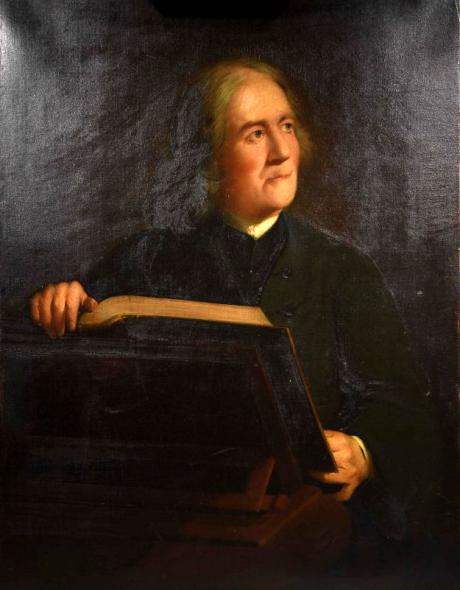

Edward Orpin came from a family of Bradford tradesmen, and had started life as a cooper before becoming a much-employed and long-serving local official. His duties in the town were various, including transcribing registers, acting as Coroner or Clerk of the Market (in which role he enforced the weights and measures laws at markets and fairs) and, as vestry clerk, doing everything from organising the church laundry to dealing with church taxes. With his long service, and his prominent historic home in the town centre (now known as Orpin House) he was a well-known local figure. There are several portraits of Orpin, the famous portrait in The Tate, (a larger and more detailed version of this one) a Portrait in the Philadelphia Art Gallery of Orpin standing with a Beadles Staff, all of these portraits have been debated at length as to their authorship.

Circumstantial evidence has lent credibility to the attribution of the portrait in the Tate to Gainsborough, despite the absence of supporting documentation. Gainsborough had connections with the Orpin family, as he was a neighbour of Edward Orpin’s son Thomas Orpin (d.1797), who was a successful music teacher in Bath.

Importantly, the painter was a friend of John Wiltshire’s father, Walter Wiltshire (1719–1799), the wealthy Bath merchant whose carrier service he used to transport paintings to London while he was based in the west country city (1760–1774). We know that Wiltshire obtained paintings directly from Gainsborough, including the famous The Harvest Waggon (Barber Institute of Arts, University of Birmingham), the painting noted as ‘well known’ by Britton (as quoted above). All the other paintings attributed to Gainsborough in the Wiltshire sale of 1867, and apparently sharing the same provenance, remain identified as works by that artist. However, it cannot be certain whether this work was owned by Walter Wiltshire or was acquired by the family at a later date (but of course, before 1814 when it was exhibited by his son).

The painting was acclaimed as a masterpiece when it was first displayed as part of the National Gallery collection of British art at South Kensington in 1867. A reporter for the London newspaper, the Standard (26 December 1867), was enraptured: The artist has drawn with his pencil as noble a portrait of the parish clerk as that the poet Goldsmith drew in verse of the country clergyman.11 The old man looks up from his Bible to the skies with inquiring gaze. Perhaps just a shade of misgiving may exist, to trouble the venerable clerk’s thoughts, but the doubt, if doubt exists, will only be transitory in the good man’s mind. We might wish for more such deserving subjects for the pencil, and for more Gainsboroughs to appreciate and do justice to them.

In 1876 the picture was introduced into a new hang at the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square, paired with the famous painting by Gainsborough of Mrs Siddons (National Gallery, London) at either side of the acclaimed landscape by the same artist, The Watering Place (National Gallery, London). The picture had already been matched to Mrs Siddons in terms of quality and importance; the leading weekly journal Illustrated London News proclaimed both were ‘unsurpassedly fine’.12 The later arrangement at the National Gallery seems to have actively invited this comparison. The novelist Charles Dickens, in an essay on the parish clerk for the popular weekly journal All the Year Round in 1880, proclaimed it ‘as fine a specimen of his delineation of men, as is his portrait of Mrs Siddons of women’ and ‘the most perfect picture of a parish clerk ever painted’.13 A journalist in 1885 similarly saw a telling contrast between the two: ‘Side by side on the same wall hang the Siddons, which is a glory of pure colour, and the Parish Clerk, which is a glory of tone’.14 Generally known simply as The Parish Clerk, the painting had become one of the most famous images of the time, valued by art critics and writers, and as ‘one of the chief ornaments of the National Gallery’ well known to a general audience,15 the subject both of jokes in comics and of considered critical judgements by well–informed commentators.16 The painting was transferred to the Tate Gallery in 1919, and its fame continued to grow in this new context: a guidebook of 1926 confirmed it was ‘deservedly a favourite example of Gainsborough’s work’.17 When it was included in the major Gainsborough exhibition at Ipswich in 1927, a reviewer referred to it as ‘suave and rather sentimental … so well known and so popular’ and in a survey of the following year, it was asserted that it showed ‘the artist at the point of his highest achievement as a painter of men’.18 By 1930 it was referred to as both ‘famous and popular’.19 A local history published in 1953 could still blandly allude to the ‘well–known painting “The Parish Clerk”’ in the expectation that their readers would be familiar with this picture.20 By this last date, in which year the picture featured in the Tate Gallery’s major Gainsborough exhibition, the pre-eminent scholar of British art Ellis Waterhouse was forming doubts about the attribution. The painting had been included in his preliminary checklist of the painter’s works published by The Walpole Society in 1953 but was to be excluded from his catalogue of Gainsborough’s paintings published as a book in 1958, a move dramatic enough to elicit a covering note from the author: Many pictures from that list [i.e. that published in the Walpole Society] have now been deliberately omitted, but the only one to which I would draw particular attention is the Orpin, Town Clerk of Bradford, in the Tate Gallery, long believed to be one of the most unimpeachably authenticated of Gainsborough’s portraits. At the Gainsborough exhibition at the Tate Gallery in 1953, where it was hung among unquestionable Gainsboroughs of all periods, it became clear that this attribution was impossible, and I can only suppose the picture is by William Hoare, whose work at Bath, during the years that Gainsborough lived there, occasionally shows some similarity to Gainsborough.21

Waterhouse’s suggestion that the painter might be the Bath artist William Hoare (1707?–92) was subsequently rejected by Tate curators, following new work on that artist by Evelyn Newby.22

The more recent re-attribution to the Irish painter Nathaniel Hone (1718–84) seems to originate with Tate curator Elizabeth Einberg and is mentioned, albeit tentatively, in a letter by her of 1986.23 Hone remains a strong possibility, and comparison with works by him such as the 1762 portrait of Sir John Fielding (National Portrait Gallery, London) and, especially, the 1773 likeness of the same sitter (Middlesex Guildhall Art Collection) may support this possibility.24 However, Hone is not known to have worked in Bath in the 1760s and 1770s, when this portrait must surely date from, and the technical and stylistic similarities are not beyond dispute. Further suggested authors include Thomas Beach, Mason Chamberlin, Robert Edge Pine and George James.25 Accoordingly, the identity of the artist remains unresolved. Although critical opinion has sided with Waterhouse’s rejection of the painting as by Gainsborough, the picture arguably bears comparison in some regards with the rather sturdier, relatively prosaic treatment of male sitters from this period, notably the portraits of Quin and, on a three-quarter length format of Uvedale Tomkyns Price c.1760–1 (Neue Pinakothek, Munich), which share the slightly hesitant, stiff treatment of anatomy and the cautious, controlled modelling of the sitters’ features. Meanwhile, the look of divinely-inspired distraction and accompanying turn of the head recall quite strongly Gainsborough’s later portraits of The Reverend Humphrey Gainsborough c.1770–4 (Yale Center for British Art and private collection, London).

The situation may be further complicated by the existence of other pictures apparently showing the same sitter. Another painting of ‘The Parish Clark’ identified as a work by Gainsborough was on sale in America in 1911. That may simply have been a copy, given the celebrity of the picture at the National Gallery, but Philadelphia Museum of Art owns a further painting of what appears to be of the same sitter, dressed in the costume and carrying the staff of a beadle (civic official) and potentially by the same painter as the Tate picture. It is possible to read the paintings as complimentary, showing the sitter attending to the secular and religious duties which made up his role as parish clerk. The painting was acquired in 1917 as a Gainsborough as part of the collection John G. Johnson (1841–1917) and is now listed as British School. A correspondent to an art magazine in 1901 also claimed to have a painting showing the same sitter as in the Parish Clerk, ostensibly in a subject painting by Gainsborough of ‘a miser’ counting coins. While it has not been possible to identify that last picture, it adds to an apparent proliferation of portraits of the same sitter in different guises, which in turn opens up the slight possibility that he was a model painted in role rather than Edward Orpin (a well-known local figure who had, though, been dead for more than thirty years when this picture was first exhibited with his name attached to it).

Notes

1 Steven Hobbs, Gleanings from Wiltshire Parish Registers, Chippenham 2010, p.23, where Orpin is noted as beginning as Parish Clerk for Bradford on Avon 1722, and retained the role until his death in 1781. The date of his birth is derived from the obituary notice, Gentleman’s Magazine, 51 (1781), p.294, where it is stated he was eighty-nine.y refers to ‘Gainsborough’s Parish Clerk’ as among the pictures apparently being mimicked by living models at Marlborough House (‘Would I like to be set in a frame as Gainsborough’s Parish Clerk? No, I should not sir. I don’t want to be set in a frame and I won’t.). For an example of the latter, the assessment in Philip Gilbert Hamerton, ‘Thomas Gainsborough’, The Portfolio, September 1894, pp.5–86 (p.80): ‘Of all Gainsborough’s pictures this is, perhaps, the most careful, the most caressing, if I may be allowed the word, in design. The flow of every line, the accent of very mass, has been pondered and re-pondered until the unity, if not the force, of Rembrandt has been reached’.

Hoare, William (1707/8–1792), portrait painter, was born near Eye, Suffolk, the eldest of the three children of John Hoare, a prosperous farmer and land agent. The family soon moved to Berkshire and William was sent to school in Faringdon where he showed an early talent for drawing. His father was persuaded to send him to London in the early 1720s, where he joined the studio of Giuseppe Grisoni, an Italian who had come to England in 1718. When Grisoni returned to Italy in 1728, he took Hoare with him. Once in Rome, Hoare shared lodgings in via Gregoriana with Peter Angillis, Laurent Delvaux, and Peter Scheemakers. He joined the studio of Francesco Imperiali, a history painter, and also frequented the studios of the French Academy nearby in the Corso. Personable and well educated, he formed lasting friendships with many young grand tourists who became his patrons: Henry Bathurst, the future third and fourth dukes of Beaufort, Robert Dingley, Henry Hoare (1705–1785) (no relation), George Lyttelton, Charles Hanbury Williams, and Joseph Spence, tutor to the future second duke of Dorset and later to the earl of Lincoln.

Hoare returned to England in 1737 or 1738. He had connections with the entourage of Frederick, prince of Wales, and drew the Prince's Portraitin pastel (ex Sothebys, 11 April 1991, lot 28), but he did not prosper and decided to move to Bath, where his brother Prince (d. 1769) was a sculptor and where the Bath seasons were to furnish him with a constant stream of sitters. He quickly came to the notice of Beau Nash and Ralph Allen, whose portraits he painted in oil (1749, Bath corporation; 1758, Exeter Health Authority). In 1742 Hoare was elected a visitor to the Mineral Water Hospital, the duty of which he performed regularly until 1779. This appointment brought him many commissions and the hospital itself still contains a fine collection of Hoare's works, including Self Portrait (pastel, 1742) and Dr Oliver & Mr Peirce Examining Patients (oil; exh. Society of Artists, 1761). He obtained a major commission for an altarpiece for the Octagon Chapel in Bath, The Pool of Bethesda (1765; Bath Masonic Hall Association). An habitué of Stourhead, he furnished the younger Henry Hoare with many family portraits still in situ. On 4 October 1742 Hoare married at Lincoln's Inn chapel, London, Elizabeth Barker (d. 1793); they had five children: Mary (1744–1820), who was also an artist, mainly in crayon, Anne (1751–1821), William jun. (1752–1809), the playwright and painter Prince Hoare (1755–1834), and Georgiana (b. 1759), who died in infancy.

Many of Hoare's old Rome acquaintances had become his patrons, and a very substantial part of his income came from politicians' portraits (for example, William Pitt the Elder,c.1754; NPG), their replicas, and the fine mezzotints by Richard Houston commissioned after them. Hoare remained in close touch with the London art milieu. He was connected to the Foundling Hospital and to the Magdalen Hospital, to which he presented a Portrait of Robert Dingley, its founder, in 1762. In 1755 he joined others in signing a request for the founding of an academy. He first exhibited publicly at the Society of Artists in 1761 and in 1769 became a founder member of the Royal Academy at the king's special request, exhibiting intermittently [see Founders of the Royal Academy of Arts]. Hoare died in Edgar Buildings, Bath, on 10 December 1792, and his wife on 30 November 1793. There is a wall tablet to both in Walcot church, near Bath, and a wall monument to Hoare by Chantrey (1828) in Bath Abbey.

Evelyn Newby