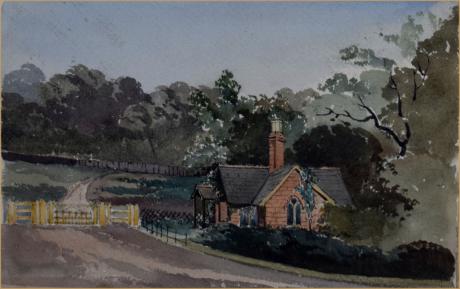

inscribed and dated in the margin "Lodge Anningsley Park , Surrey, 1862"

Cherry Rise, Anningsley Park, Ottershaw, Chertsey, Surrey KT16 0QU

In 1781, Thomas and Esther Day moved from their previous house, a damp cottage in Stapleford-Abbots in Essex, to Anningsley which Day had purchased along with large parts of the nearby Surrey countryside – areas in Chertsey, Egham and Cranleigh. Their two-storey, mid-eighteenth-century house was situated at the time in what was then rural and desolate countryside, where only a few poverty-stricken land-labourers resided.

Thomas Day shied away from the few members of the aristocracy who lived nearby and they considered him a misanthrope in return. The Days had just two or three servants and, extraordinarily, owned no carriage, having nobody nearby to visit.

Spending the 1780s in the seclusion of Anningsley, Thomas Day carefully divided his time between reading, writing, and performing tasks on the farm, which was tended to by a large workforce. The farm was not a commercial venture but the realisation of Thomas Day’s ideal world, in which the greatest form of charity was to offer someone employment, rather than let them depend on poor relief.

Refusing to become wealthy from the labour of those poorer than him, Thomas Day boasted a £300 annual loss on his farm and allowed his workers an extra shilling for clothes and meat during the winter months.Locals heckled Thomas Day, pointing out that employing labourers was totally unnecessary during winter, when all work on the farm was frozen.

His dislike of the parish relief system led Thomas Day to take the strange decision to wage his farm labourers during winter, even though there was no work to do. The relief the parish offered them was barely sufficient to support most healthy families.

Decades before the nineteenth century philanthropists and Edwin Chadwick’s 1834 Poor Law reforms, Thomas Day was setting a precedent for a fairer system. Up until the mid-nineteenth century, wages were below the subsistence level, which was met only with help from parish relief. This left the labourer at the mercy of the parish for the whole winter, but suited a miserly farm owner well.

As a man who had inherited a large fortune, Day equally despised the idea that he should be entitled to feast and profit from the labour of others, simply because he was their employer. Thus, in his locality in Chertsey, the philosopher created his miniature welfare state and found it thriving.

Many farm labourers did not appreciate their employer’s philosophy and work regime. Thomas Day despised the expensive and extravagant lifestyle of his contemporaries but his sparing, reclusive and Spartan lifestyle did not enamour his employees either – they thought he was a miser. It was mostly the kind and caring Esther Day, who understood Thomas and could explain his actions to others.

Thomas Day turned his studies to the benefit of those around him. Workers from around Anningsley would turn to Thomas Day for medical advice and attention and would be nursed back to health by Esther, as well as treated to dinner at the Days’ table. Mr. Day did not overlook more challenging maladies and illnesses, writing to his Lunar Society friends, Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of the famous naturalist) and Dr. William Small, for some of the best medical advice that could be afforded in Georgian England.

Central to the medical attention which Day learned to give those in his charge was just one piece of advice: keep your house ventilated. Thomas Day despised air pollution and committed himself to filling the unsightly heaths around Anningsley with the pine trees which still stand there today. He also advised his farm workers to avoid public houses such The Otter, in nearby Ottershaw.

Day had his own unique approach to charity which spurned Christian traditions. He was scornful of the organised, parish-based charity believing that a man is happier and more dignified when given the opportunity to work for his keep. In a letter to Richard Lovell Edgeworth, he once wrote, ‘What is the lot of man in every country? To labour, and eat his bread by the sweat of his brow.’

Thomas did read the Bible, however, and he and Esther took responsibility for the religious instruction of the children in the area. Thomas read from the Scriptures on wet Sundays when the weather prevented the villagers from trekking to Horsell for the service at St. Mary’s.

Thomas and Esther dedicated themselves tirelessly to occupying the community in beneficial activities. Thomas ran his farm around the calendar and Esther engaged labourers’ wives and daughters in knitting stockings and clothing whole families, paying for the fabric and labour in lieu of those poorer locals who could not afford the clothes themselves.

Though Esther Day was forbidden by Thomas to practice her music (she loved the harpsichord), the family allowed themselves one expense, the library. Books contained invaluable ideas, and Day made space in Anningsley’s living room for a library.

Ottershaw is situated in open woodlands in the Borough of Runnymede in northwest Surrey. The A320 links the village with Chertsey to the north and Woking to the south.

The whole area was originally heathland, part of the waste of the Manors of Walton on Thames and Walton Leigh, located on Chertsey Common in the Windsor Forest. The payment of tithes was to the manor of Chertsey Beomond as a result of a dispute in the 13th century between the Abbot of Chertsey Abbey and Rector of Walton on Thames that went all the way to the Pope in Rome. Chertsey Abbey won, so for a small area the history is quite complicated!

During the 16th century small farms were established in the wasteland – Brox, Bousley, Potters Park and Spratts. These remained as farms until the 19th century when they became nurseries supplying vegetables and cut flowers to London. The daily journey to Covent Garden could just be made by horse and cart. The two farms of an earlier date Anningsley and Ottershaw came under more wealthy lessees from London in the 16th and 17th centuries, who rebuilt them as their country houses and parks, as well as farms.

The labourers lived in small daub/stone cottages in the three hamlets of Brox, Spratts and Chertsey End Lane. These often had to be rebuilt, hence there are few truly old buildings in the village. Slowly these were replaced with more modern houses, and in particular after World War 2 there was a steady growth along the roads with closes of houses at the back on the former nursery land.It was not until the mid-19th century that the name of Ottershaw, from the estate of that name, came into general use as the village name. At this time Sir Edward Colebrook, owner of Ottershaw Park, provided the land and paid for the fine church, whose architect was Sir Gilbert Scott. Thus Ottershaw became a separate parish from Chertsey.