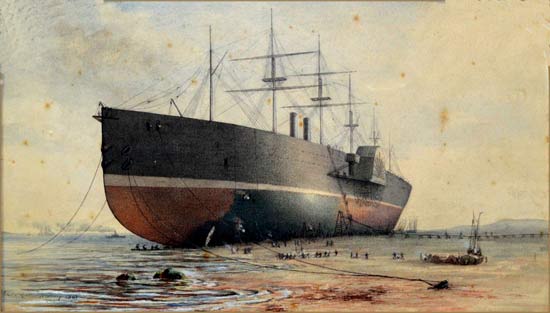

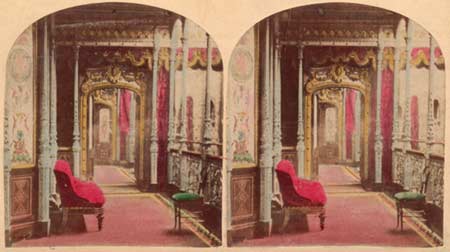

signed and dated 1867

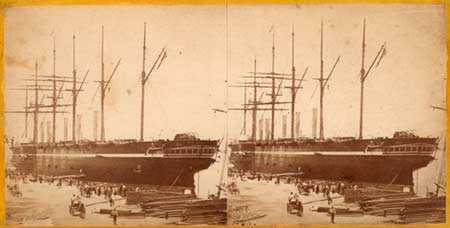

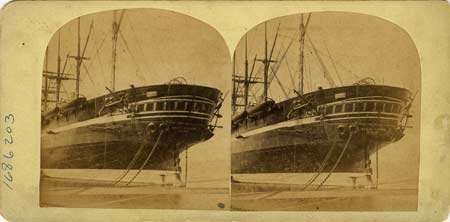

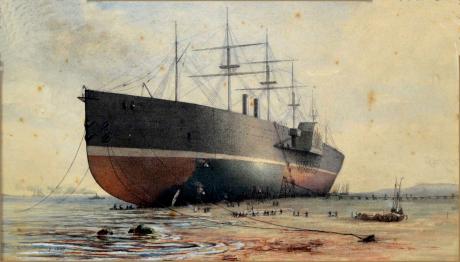

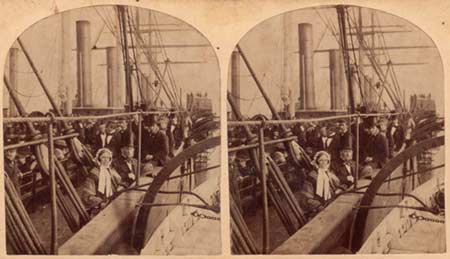

The Great Eastern was placed on the Grid Iron at New Ferry on the 19th January 1867. The Gridiron on which the ship rested was constructed in 1864 when the vessel was first overhauled in the Mersey, but has since been altered strengthened and very much improved . There was a very high spring tide, and although the ship was drawing 18 feet 6 inches of water on an even keel, there was quite sufficient depth on the shore to render the operation of beaching a safe one. She lies broadside on the grid running parallel with the river. About nine o'clock a.m. all was in readiness, and the ship left her moorings. Sir James Anderson, the commander of the big ship, attended to the navigation, while Mr. Brereton, the successor to Mr. Brunei, and Mr. Yockney, carefully watched the engineering depart- ment. Four steam-tugs (two on each side the Great East-) ern assisted to keep the vessel in position, as with scarcely perceptible motion she neared the beach. The screw engines only of the big1 ship were worked. Tie screw boilers have been taken out of the ship, and are to be replaced by new ones, and the screw engines were consequently worked from the paddle boilers. The big ship took the grid about ten o'clock. She was placed with great nicety in the exact position fixed upon. Every- thing passed off without the slightest accident, and the beaching may be said to have been accomplished in the most skillful and successful manner. The Great Eastern is kept in position by two massive dolphins. Although her sides and bottom are rather dirty, the lines, bolts, and rivets appear in excellent order. The gridiron is perfectly flat for 60 feet wide, and the big ship rests in perfect security upon it. Every precaution has been taken to prevent accident. Thousands of men are at present engaged on the ship, and she will be ready at the time specified to trade between New York and Brest. Her first voyage after she comes off the grid- iron will be from Liverpool to New York, with goods and passengers.

In March 1867 some of the intended work was for 200 men to men to scrape off growth and barnacles from the bottom of the ship and apply McInnes Patent Preservative composition , the copper paint when dried adopts the texture of polished marble with a dark green colour , which preserves the iron plates from rust and protects the plates from marine life growth . The Plate Lines were as clear and as distinct as when she first left Millwall when she was launched. The deck-House fore and aft were refurbished as well as the internal decorations. The Operation took several weeks , while the Leviathan was beached on the Gridiron before being moved to her moorings at Sloyne. The operation was superintended by Captain Sir James Anderson, Mr Brereton, C.E. And Mr Jocking. The Great Eastern Left on the 20th March 1820 and proceeded to New York to bring passengers to view the Paris International Exhibition. According to a local account , " It is said that Mr Mcinnes sulphate of copper composition was shoveled off, with the shelly mass adhering to from 4 to 9 inches thick leaving the under coatings of red lead generally intact. There were I learn , tight coats of red lead over the iron bottom before Mcinnes solution was applied . Under the red lead the plates and rivets were perfect, but where the red lead had been chafed off, there corrosion had set in and rivets had to be removed . The quantity of mussels and other crustacea and marine life has been variously estimated to 100-150 tons in weight. Including the Mcinnes Patent Preservative composition several coats or varnish and Iron mixed were applied so as to form a barrier between the copper composition the plates and rivets. Sold late in 1887, Great Eastern went back to New Ferry Liverpool, where she was stripped and slowly broken up during 1888 and 1889.

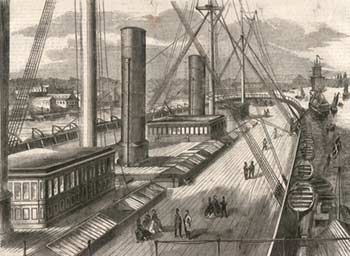

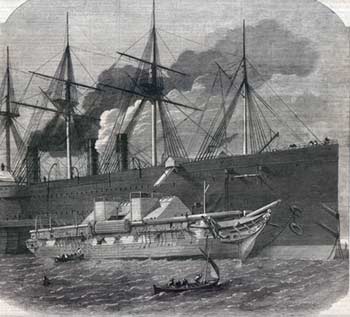

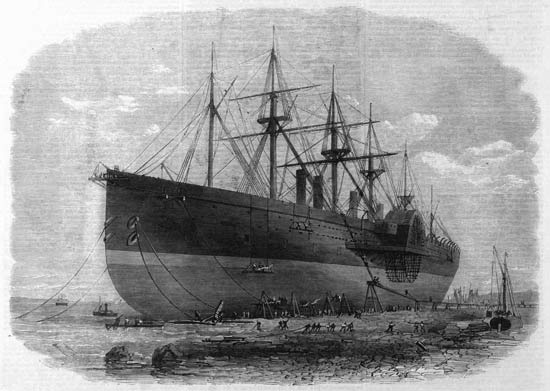

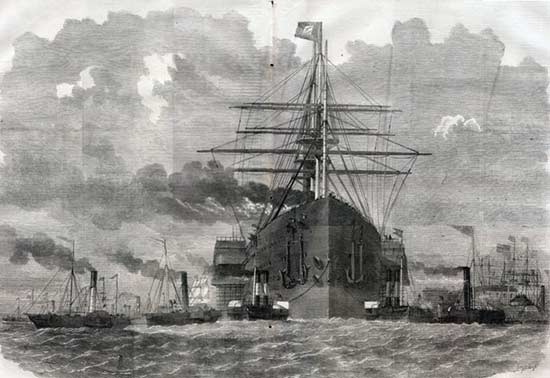

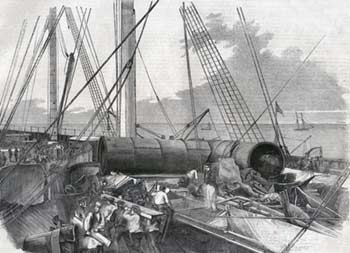

Edwin Arthur Norbury worked for the Illustrated London News, which often featured stories on Great Eastern and the Atlantic cables. Searching the ILN archive for 1867, there is a brief story on the refit in the issue of 16 February 1867, and a couple of pages later, a wood engraving showing the ship. The illustration is almost identical to the watercolour, but with four funnels (of which the two ones aft are a bit sketchy), and was obviously created by the ILN's wood engravers from Norbury's watercolour.

reproduced Illustrated London News Illustrated London News, in the issue of 16 February 1867

Marc Isambard Brunel was born in Normandy, France in 1769. When he reached maturity he served in the French navy for six years. When this term of service was completed in 1792 he returned to France to find the French Revolution raging in full fury. Because of his royalist sympathies he decided to emigrate to the United States. He reached New York in 1793 and commenced a career in New York as an architect and civil engineer. He was successful as an architect, but his most outstanding accomplishment was the design of equipment for an arsenal and cannon factory. This project required his invention of new devices. After six years in New York Marc Isambard Brunel decided to emigrate to England. He sailed in 1799 with plans for new equipment to manufacture the block and tackle equipment (multiple pulleys) used on ships to manipulate sails. It took until 1803 to get approval from the British government and begin construction at the Portsmouth dockyard.

Marc Isambard Brunel also invented new machines for the processes involved in the construction of ships and by 1812 he had been commissioned by the British government to build sawmills at Woolrich and Chatham. His mind was exceeding productive. During the period from 1812 he interested himself in a wide variety of endeavors. Some of these pursuits resulted in patents. Yet despite his fertile intellect, or perhaps because of it, he found himself in such financial difficulties that in 1822 he was incarcerated for nonpayment of his debts. Actually his financial troubles stemmed from two major setbacks: 1. A fire which destroyed some of his facilities, 2. The government refusing to make payment for a consignment of military boots manufactured by a Brunel enterprise. A war Britain had been engaged in, ended sooner than people expected and the government knew it would not need the boots. Brunel's friends secured a government grant of five thousand pounds for Brunel to use to pay his debts and gain his freedom. Before he went to prison he started designing bridges and when he was released he gained the commission to construct some of those bridges. He conceived a plan to excavate a tunnel under the Thames and in 1824 a company was formed to carry out this project. It took until 1843 to complete that tunnel. Marc Isambard Brunel died in 1849.

His son, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, was born in 1806. His middle name Kingdom was his mother's maiden name. When he reached the age of 14 he was sent to France to study engineering. There probably were several factors behind the elder Brunel sending his son to France for his education. Probably foremost was that in the period before the Industrial Revolution France exceded England in science and engineering. Undoubtebly the French background of the Brunel family was another factor. The son joined the father's engineering firm in 1823, about the time the Thames tunnel project was being prepared. The son, Isambard Kingdom, became the lead engineer for the project at the early age of 19. He continued as the Thames Tunnel engineer until 1828. The son then went on to design bridges.

In 1833 Isambard Kingdom Brunel at the relatively young age of 27 was appointed chief engineer for the Great Western Railway. A major part of his responsibility was the design and supervision of the construction of railway bridges. He achieved fame for his expertise in bridge design.

He could not limit his vision to railways. By 1835 he was conceiving of an extension of the Great Western Railway connecting with a steamship which would journey to New York. The ship was to be called The Great Western. His company accepted the project and Brunel designed and supervised the construction of The Great Western in 1838. It was the largest steamship of its time and the first to make regularly scheduled journeys across the Atlantic. The Great Western was a great success.

Brunel's next ship, The Great Britain was roughly twice the scale of The Great Western. Brunel intuitively understood the economy of scale in ships. If the scale of a ship is increased by a factor of two so it is twice as long, twice as wide and twice as deep then the volume increases by a factor of eight but the surface area increases only by a factor of four. The construction cost is closely linked to the surface area because it is the area that determines the amount of construction material for the hull. The The Great Western was constructed of wood but Brunel chose to use iron for the hull of The Great Britain. For a ship the size of The Great Britain it was not practical to use wood. If the same material is used for the double scale ship the cost per unit volume decreases by 50 percent. With Brunel using a more expensive material for the double scale ship the net result was that the cost per unit of volume decrease but not by as much as 50 percent.

The The Great Britain used a screw propellor for propulsion. It was the first ship to do so. The Great Britain was a great success. It appeared that Brunel's ship based upon the same economy of scale principle would also be a great success. But there appeared to be something operating analogous to the Peter Principle ("People rise to the level of their incompetence.")In the 1850's Isambard Kingdom Brunel was acknowledged to be Britain's greatest engineer. He had achieved fame and fortune in designing and supervising the construction of tunnel, bridges and other structures for railroads. When he had become tired of railroads and was seeking new engineering realms to conquer he designed shipping docks and piers. He then rose to the peak of naval engineering when designed the two largest ships of their time, The Great Western (1837) and The Great Britain (1843). These ships were powered by a combination steam and sail. The Great Western was constructed of wood and was of conventional design. For his second ship, The Great Britain, he went to iron for structure and a special design to take advantage of the greater strength of iron. The Great Britain was 322 feet long and 50 feet wide when conventional wooden ships were no more than 150 feet long. The Great Britain went into service for the run between Great Britain and Australia and was a great financial success.

Althought The Great Britain was considered to have been the largest ship built up to that time there were larger ships built in the Chinese Empire in the early 15th century. The treasure ships of Zheng He were 440 feet long and there were over three hundred of them. The fleet carried a crew of 37 thousand. China was close to five hundred years ahead of the West in the early 1400's. At about 500 BCE China was a millenium or two ahead of the West and the Middle East in technology. The Empire put scholar-bureaucrats in charge of the society and China stagnated. Brunel decided to redouble the scale for his third ship. It was to be 692 feet long, 120 feet wide and 58 feet deep. It was to be constructed of steel and iron and steam powered but would have six masts for sails. Brunel wanted his ship to be powered by three sets of steam engines; one set for the screw propellor at the stern and two sets for side paddle wheels.

Brunel began the serious work for his Great Ship project in 1852. He chose the name Leviathan for the ship and it was christen so, but the public would not have it named anything except The Great Eastern. Brunel contacted John Scott Russell (of soliton fame) who was the leading naval architect of the time. The collaboration of Brunel and Russell was initially quite fruitful but later became troubled. At Russell's suggestion the ship design was presented to the Great Eastern Steam Company. The company responded favorably to the proposal and this led to the formation of a company to undertake the building of the Great Ship. Soon the ship was known as The Great Eastern Directors for the company were found and shares of stock in the company were sold.

The company solicited bids for the construction of the ship. Brunel estimated that the cost would be in the neighborhood of £500,000. John Scott Russell's bid was the lowest. Russell proposed to build the ship for £377,000, of which £275,200 would be for the hull, £60,000 would be for the engine to drive the screw propellor and £42,000 would be for the boilers and engines for the two paddle wheels. What the board of directors of the company did not realize when it accepted Russell's low bid was that Russell was unrealistically optimistic and that once it accepted his bid and committed itself it would not be able to enforce the contract with Russell to get the ship built at his low price.

Russell was not financially secure, particularly after a calamitous fire destroyed his ship yard. This meant that Russell needed prepayments to finance the ship's construction whereas the company was presuming that the payments would be made on the basis of work completed. The other factor that made the enforcement of the low bid cost impossible was that Brunel, as chief engineer of the project, insisted upon complete control of the project. This meant that elements of the construction process had to be Brunel's decision. This led Russell to argue that the provisions of the contract were being violated because of changes in the construction process. One of the most important of these construction decisions was the matter of how the ship hull was to be launched. The Great Eastern was more than twice as long as the previously largest ship and more than four times as long as the typical ship of the time. No existing dry docks could accommodate her construction. Brunel chose to have the ship hull built parallel to the Thames River where it would be launched by sliding its 12,000 ton weight sideways 200 feet. Brunel insisted upon a controlled launch rather than a free launch in which the hull would slide under the effect of gravity. This would prove to be easier to plan than to execute.

Russell's impecuniousness and the company's unwillingness to accommodate his financial needs led him to pursue financial solutions that not only put him at financial risk but threaten not only his solvency but the completion of the ship. Russell mortgaged his shipyard to get funds to meet his operating costs, but this mortgage committed him to payments which if not met would lead to the confiscation of properties which were required to complete the hull of the ship. John Scott Russell's forte was applied science rather than organizational and financial administration. For example, one of the issues was the inadequate safeguarding of supplies at his construction site. There was an enormous amount of iron unaccounted for and probably lost to pilfering. This loss increased Russell's costs substantially and contributed to his financial difficulties.

At one point Russell, in financial desperation, undertook the building of severl smaller ships for other clients. The construction of these ships precluded making progress on the construction of the great ship for Brunel. At the point at which Brunel lost confidence in Russell only one fourth of the construction had been completed yet Russell had received more in payments than his contract called for the completion of the entire hull. When Russell was on the verge of bankruptcy Brunel's company took possession of the shipyard and the hull on the basis of Russell having breached his contract. This was to prevent the mortgage company of Russell from executing such a takeover. In the negotiations between Brunel and the mortgage company Brunel committed the company to a September 1856 launch date for the hull. There were penalties for not executing the launching by the agreed upon date. It turned out that it was not possible to meet the September deadline. A launching in early November 1856 appeared to be feasible. The launching could only be achieved on the date of high tide for the month. Unfortunately the controlled launching turned out to be so difficult that the actual launch was achieved only on January 31, 1857. The launch had been attempted on November 3, 1856, attempted again on December 2 and again at the high tide of the New Year.

The difficulty with the launch was that tug boats in the Thames were pull by means of chains on the 12,000 ton hull while hydraulic rams pushed from the land side. The chains failed under the stress. By the time of the launching of the hull the cost had reached £732,000. There was another important cost and that was the destruction of Brunel's health. Brunel was only in his early fifties but his health had deteriorated under the stress of 18 hour days to the point he could no long go on.

It was only the hull which was launched. The hull then had to be towed to another site where it was to be outfitted with equipment. After The Great Eastern was outfitted the maiden voyage was scheduled for September 7, 1858. Brunel was ready to join that maiden voyage when, September 5th, he suffered at severe stroke that incapicitated him. He died ten days later. He was only 53 years old. Even Brunel's last days were marred by another disaster for The Great Eastern. On the return from her maiden voyage one of the steam jackets for a funnel exploded. The valves on water jackets of two funnels associated with the paddle wheel steam engines had been mistakenly closed. Fortunately the error was discovered and a second explosion avoided. Twelve crewmen were injured in the explosion, five of them fatally.

In January of 1860 the captain of the Great Eastern, a man who had been personally chosen by Brunel, was drowned along with three other crew members when the small boat they were riding in capsized in a storm while trying to reach the Great Eastern. Whenever a tragedy occurred for The Great Eastern a story resurfaced that explained it as a resulted of the ship being haunted. The Great Eastern had two hulls separated by a distance of almost three feet. The riveters often worked in that space and the story went that a riveter and his boy helper had been accidently enclosed while working in that space and their ghosts were haunting the ship. In the nineteenth century tales of the natural were an important aspect of life. But so many unfortunate things happened to The Great Eastern that it was easy to believe that the ship was jinxed.

The Great Eastern had not made the journey to Australia which she was built for. Since the loss of the ship captain and financial difficulties made it unlikely that that journey would be undertaken in the near future the owners converted her to a luxury liner for trips across the Atlantic to New York. The first trip could hardly have been a profitable voyage since she carried only 38 passengers but a crew of 418. The Great Eastern was designed to carry 4000 passengers. This first passage was uneventful and she was celebrated when she arrived in New York. In September the great ship was ready for another trans-Atlantic crossing and this time she carried 400 passengers. This time however the voyage was anything but uneventful. The ship ran into a hurricane. The large waves were causing the ship to lean and this submerged the paddle wheel on one side. That paddle wheel had to be shut down, but this deprived the ship of a major portion of her propulsion and hampered her maneuverability. The Great Eastern could not be turned into the wind and one paddle wheel was broken off of the ship by a great wave. Additionally the ship's rudder was damaged to the point of being useless for steering. Worse yet the rudder was being battered by the screw propellor and so the screw propellor had to be turned off. The great ship was helpless at sea in a hurricane.

After the crew managed at great personal risk to chain the rudder to immobilize it the screw propellor could again operate and propel the ship. The ship made it back to Britain, but the cost of repairing the damage was £60,000. The repaired Great Eastern returned to trans-Atlantic passages. In August of 1862 she was carrying 1500 passengers when she again ran into a violent storm. Off Long Island the ship passed over a submerged rock that cut a gash in the bottom of the outer hull 85 feet long and 5 feet wide. The inner hull was not damaged but the repair of the bottom of such a large ship was no easy matter.

During a period in which the ship was being repaired the workmen heard what sounded like a knocking coming from inside the hull. The workmen thought it was the ghosts of the trapped riveters and refused to continue the repairs. An investigation found that the knocking was just the result of a loose chain. The repairs were finished in December of 1862, but at a cost of £70,000. The Great Eastern made a few more trips across the Atlantic but lost £20,000. The sip owners reviewed the situation and decided to sell the Great Eastern at auction. The ship which had cost close to £1 million to build brought a price of only £25,000.

The new owners decided to convert the ship into an oceanic cable layer. They leased her to the Atlantic Telegraph Co. for £50,000 and in July of 1865 the Great Eastern, after refitting, began to lay cable from Ireland to Newfoundland. After laying a thousand miles of cable, worth £700,000, the cable end was lost in about six thousand feet of water and could not be recovered. Despite this failure the cable company tried again in July of 1866 with stronger cable and this time they were successful. On top of this success the ship was taken back to where the first cable was lost and the old cable was retrieved.

For three years the Great Eastern successfully laid cable in various parts of the world's oceans. But newer ships specifically designed for laying cable were entering the field and the Great Eastern became obsolete as a cable layer. She could not go back to carrying cargo and passengers. The Suez Canal was completed by this time and the Great Eastern was too wide to use the Canal. The Great Eastern was stored for twelve years while the owners tried to find a new use for her. They gave up and in 1885 they auctioned her off once again. This time she brought £26,000 whose business was hauling coal. That buyer did not put her into service hauling coal, but instead leased her to someone who converted her into a place for manufacturers to exhibit their products. After that lease expired there was nothing to do but to auction her off for scrap. She brought £16,000 in the auction. The Great Eastern of course contained far more than £16,000 worth of metal but it was so expensive to dismantle her that the buyers lost money even at a price of £16,000. It took 200 men working around the clock for two years to demolish her.

SS Great Eastern was an iron sailing steamship designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and built by J. Scott Russell & Co. at Millwall Iron Works on the River Thames, London. She was by far the largest ship ever built at the time of her 1858 launch, and had the capacity to carry 4,000 passengers from England to Australia without refuelling. Her length of 692 feet (211 m) was only surpassed in 1899 by the 705-foot (215 m) 17,274-gross-ton RMS Oceanic, her gross tonnage of 18,915 was only surpassed in 1901 by the 701-foot (214 m) 21,035-gross-ton RMS Celtic, and her 4,000-passenger capacity was surpassed in 1913 by the 4,935-passenger SS Imperator. The ship's five funnels were rare and were later reduced to four. It also had the largest set of paddle wheels.

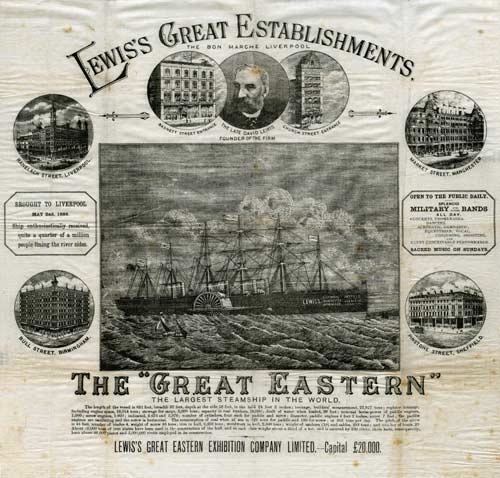

Brunel knew her affectionately as the "Great Babe". He died in 1859 shortly after her maiden voyage, during which she was damaged by an explosion. After repairs, she plied for several years as a passenger liner between Britain and North America before being converted to a cable-laying ship and laying the first lasting transatlantic telegraph cable in 1866.[4] Finishing her life as a floating music hall and advertising hoarding (for the department store Lewis's) in Liverpool, she was broken up on Merseyside in 1889.

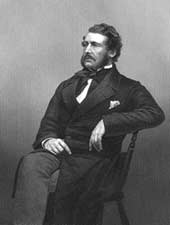

The famous photograph by Robert Howlett of Brunel before the ship's launching chains . After his success in pioneering steam travel to North America with Great Western and Great Britain, Brunel turned his attention to longer voyages as far as Australia and realised the potential of a ship that could travel round the world without the need of refuelling. On 25 March 1852, Brunel made a sketch of a steamship in his diary and wrote beneath it: "Say 600 ft x 65 ft x 30 ft" (180 m x 20 m x 9.1 m). These measurements were six times larger by volume than any ship afloat; such a large vessel would benefit from economies of scale and would be both fast and economical, requiring fewer crew than the equivalent tonnage made up of smaller ships. Brunel realised that the ship would need more than one propulsion system; since twin screws were still very much experimental, he settled on a combination of a single screw and paddle wheels, with auxiliary sail power. Although Brunel had pioneered the screw propeller on a large scale with the Great Britain, he did not believe that it was possible to build a single propeller and shaft (or, for that matter, a paddleshaft) that could transmit the required horsepower to drive his giant ship at the required speed.

Brunel showed his idea to John Scott Russell, an experienced naval architect and ship builder whom he had first met at the Great Exhibition. Scott Russell examined Brunel's plan and made his own calculations as to the ship's feasibility. He calculated that it would have a displacement of 20,000 tons and would require 8,500 horsepower (6,300 kW) to achieve 14 knots (26 km/h), but believed it was possible. At Scott Russell's suggestion, they approached the directors of the Eastern Steam Navigation Company.

The Eastern Company was formed in January 1851 with the plan of exploiting the increase in trade and emigration to India, China and Australia. To make this plan viable they needed a subsidy in the form of a mail contract from the British General Post Office, which they tendered for and Brunel started the construction of two vessels, Victoria and Adelaide. However, in March 1852 the Government awarded the contracts to the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, even though the Eastern Company's tender was lower. This left them in the position of having a company without a purpose.

Brunel's large ship promised to be able to compete with the fast clippers that currently dominated the route, as she would be able to carry sufficient coal for a non-stop passage and the company invited him to present his ideas to the board. He was unable to attend due to illness and Scott Russell took his place.

The Company then set up a committee to investigate the proposal, and they reported in favour and the scheme was adopted at a board meeting held in July 1852. Brunel was appointed Engineer to the project and he began to gather tenders to build the hull, paddle engines and screw engines. Brunel had a considerable stake in the company and when requested to appoint a resident engineer refused in no uncertain terms: I cannot act under any supervision, or form part of any system which recognises any other advisor than myself ... if any doubt ever arises on these points I must cease to be responsible and cease to act. He was just as firm in the terms for the final contract where he insisted that nothing was to be undertaken without his express consent, and that procedures and requirements for the construction were specifically laid down.

Although Brunel had estimated the cost of building the ship at £500,000, Scott Russell offered a very low tender of £377,200: £275,200 for the hull, £60,000 for the screw engines and boilers, and £42,000 for the paddle engines and boilers. Scott Russell even offered to reduce the tender to £258,000 if an order for a sister ship was placed at the same time. Brunel accepted Scott Russell's tender in May 1853, without questioning it; Scott Russell was a highly skilled shipbuilder and Brunel would accept an estimate from such an esteemed colleague without question.

In early 1854 work could at last begin. The first problem to arise was where the ship was to be built. Scott Russell's contract stipulated that it was to be built in a dock, but Russell quoted a price of £8,000–£10,000 to build the necessary dock and so this part of the scheme was abandoned, partly due to the cost and also to the difficulty of finding a suitable site for the dock. The idea of a normal stern first launch was also rejected because of the great length of the vessel, also because to provide the right launch angle the bow of the ship would have to be raised 40 feet (12 m) in the air. Eventually it was decided to build the ship sideways to the river and use a mechanical slip designed by Brunel for the launch. Later the mechanical design was dropped on the grounds of cost, although the sideways plan remained.

Having decided on a sideways launch, a suitable site had to be found, as Scott Russell's Millwall, London, yard was too small. The adjacent yard belonging to David Napier was empty, available and suitable, so it was leased and a railway line constructed between the two yards for moving materials. The site of the launch is still visible on the Isle of Dogs. Part of the slipway has been preserved on the waterfront, while at low tide, more of the slipway can be seen on the Thames foreshore. The remains of the slipways, and other structures associated with the launch of the SS Great Eastern, have recently been surveyed by the Thames Discovery Programme, a community project recording the archaeology of the Thames intertidal zone in London[when?].

Great Eastern's keel was laid down on 1 May 1854. The hull was an all-iron construction, a double hull of 19 mm (0.75 in) wrought iron in 0.86 metres (2 feet 10 inches) plates with ribs every 1.8 m (5.9 ft). Internally, the hull was divided by two 107 m (351 ft) long, 18 m (59 ft) high, longitudinal bulkheads and further transverse bulkheads dividing the ship into nineteen compartments. Great Eastern was the first ship to incorporate the double-skinned hull, a feature which would not be seen again in a ship for several decades, but which is now compulsory for reasons of safety.

She had sail, paddle and screw propulsion. The paddle-wheels were 17 m (56 ft) in diameter and the four-bladed screw-propeller was 7.3 m (24 ft) across. The power came from four steam engines for the paddles and an additional engine for the propeller. Total power was estimated at 6 MW (8,000 hp). The specific requirements of the Eastern Company also vindicated Brunel's initial concept of using both paddlewheels and a screw. The Great Britain had a chain drive 'overdrive' gear so that the slow-turning marine steam engines of the day could drive a screw propeller of a suitably small diameter while making the required thrust. This had proven troublesome and in his new ship Brunel resolved to use direct drive, requiring the much larger propeller.[8] To be effective this had to be fully submerged at all times, fixing the ship's minimum practical draught while using screw propulsion at around 7.62 m (25.0 ft). Brunel designed the Great Eastern to have a maximum draught of 9.144 m (30.00 ft). The Company required that the ship be able to dock at Calcutta, where navigation was restricted by the shallow Hooghly River which required a draught of no more than 7.0 m (23.0 ft). Brunel calculated that the ship would be able to carry enough coal to steam from Calcutta to a British port while not exceeding that draught, while if the ship took on coal for the final leg of her homeward voyage at Trincomalee instead she would be able to transit the Hooghly with a full load of passengers and cargo while drawing 6.09 m (20.0 ft). This would leave around half of the top-most blade of the screw clear of the water, greatly reducing the thrust it developed and the efficiency of the engines. Thus when operating at lighter loads and shallow draughts, the Great Eastern would require paddlewheels. After consultation with Joshua Field, Brunel set the power of the two sets of engines so that the Great Eastern's paddlewheels provided about a third of the total mechanical propulsion, with the screw propeller providing the majority.

She also had six masts (said to be named after the days of a week – Monday being the fore mast and Saturday the spanker mast), providing space for 1,686 square metres (18,150 sq ft) of sails (7 gaff and max. 9 (usually 4) square sails), rigged similar to a topsail schooner with a main gaff sail (fore-and-aft sail) on each mast, one "jib" on the fore mast and three square sails on masts no. 2 and no. 3 (Tuesday & Wednesday); for a time mast no. 4 was also fitted with three yards. In later years, some of the yards were removed. Her maximum speed was 24 km/h (13 knots). At the beginning of February 1856, Brunel advised the Eastern Company that they should take possession of the ship to avoid it being seized by Scott Russell's creditors. This caused Scott Russell's bankers to refuse to honour his cheques and foreclose on his assets and on 4 February Scott Russell suspended all payments to his creditors and dismissed all his workmen a week later.

Russell's creditors met on 12 February and it was revealed that Russell had liabilities of £122,940 and assets of £100,353. It was decided that his existing contracts would be allowed to be completed and the business would be liquidated. He issued a statement to the Board of the Eastern Company in which he repudiated his contract and effectively handed the uncompleted ship back to them. When the situation was reviewed it was found that three-quarters of the work on the hull had not been completed and that there was a deficit of 1,200 tons between the amount of iron supplied and that used on the ship. Brunel, meanwhile, wrote to John Yates and instructed him to negotiate with Scott Russell for the lease of his yard and equipment. Yates replied that Scott Russell had mortgaged the yard to his banker and that any negotiation would have to be with the bank, who after weeks of wrangling agreed to lease the yard and equipment until 12 August 1857.

The Eastern Company began the task of completing the ship. Work recommenced in May and took longer than expected to complete. Brunel reported in June 1857 that once the screw, screw shaft and sternpost had been installed the ship would be ready for launching. However, the launch ways and cradles would not be ready in time since the contract for their construction had only been placed in January 1857. Under pressure from all sides, the lease of the shipyard costing £1,000 a month, and against his better judgement, Brunel agreed to launch the ship on 3 November 1857 to catch the high tide.

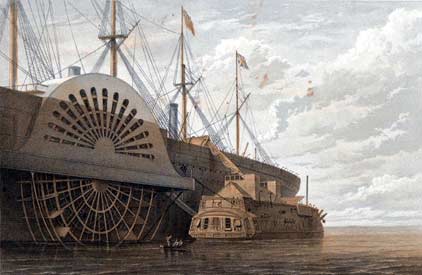

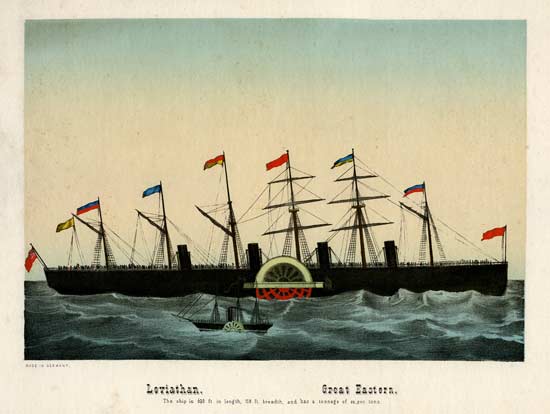

Hand-coloured lithograph of the SS Great Eastern, the great ship of IK Brunel as imagined by the artist at her launch in 1858

Brunel had hoped to conduct the launch with a minimum of publicity but many thousands of spectators had heard of it and occupied vantage points all round the yard. He was also dismayed to discover that the Eastern Company's directors had sold 3,000 tickets for spectators to enter the shipyard.

As he was preparing for the launch, some of the directors joined him on the rostrum with a list of names for the ship. On being asked which he preferred, Brunel replied "Call her Tom Thumb if you like". At 12:30 pm Henrietta (daughter of a major fundraiser for the ship, Henry Thomas Hope) christened the ship Leviathan much to everyone's surprise since she was commonly known as Great Eastern; her name subsequently changed back to Great Eastern in July 1858.

The launch was, however, unsuccessful as the steam winches and manual capstans used to haul the ship towards the water were not up to the job. Brunel made another attempt on the 19th and again on the 28th, this time using hydraulic rams to move the ship, but these too proved inadequate. The ship was successfully launched sideways at 1:42pm on 31 January 1858, aided by an unusually high tide and strong winds and using more powerful hydraulic rams supplied by the then-new Tangye company of Birmingham, the association with such a famous project giving a useful fillip to the fledgling company.

She was 211 m (692 ft) long, 25 m (82 ft) wide, with a draught of 6.1 m (20 ft) unloaded and 9.1 m (30 ft) fully laden, and displaced 32,000 tons fully loaded. In comparison, SS Persia, launched in 1856, was 119 m (390 ft) long with a 14 m (46 ft) beam. As of 2015 the site of launch is still partly visible next to Burrell's Wharf on the Isle of Dogs. In 1857, during the planning of the Suez Canal, it was thought that Great Eastern would not be able to traverse it, since she had a draught of 28 ft (8.5 m) and it was expected that the canal would be excavated to a depth of 26 ft (7.9 m). In any event, when the canal was opened to shipping in 1869, Great Eastern was no longer in passenger service.

The launch of the ship cost £170,000, a third of Brunel's estimate for the entire vessel, and it had yet to be fitted out. It was difficult to get any more money from the Eastern Company's investors as the company was close to bankruptcy. To prevent this from happening, a new company was formed, the "Great Ship Company", with capital of £340,000. They bought the ship for £160,000, which left enough funds for fitting her out. The Eastern Company's shareholders were given the market value of their £20 shares (£2 10s) towards payment for shares in the new company and the Eastern Steam Navigation Company entered liquidation.

Tenders were invited for fitting the ship out, and two were received – one from Wigram and Lucas for £142,000, and the other from John Scott Russell for £125,000. Brunel had taken a long holiday on medical advice and was absent when the contract was awarded to Scott Russell. The work was begun in January 1859, and was completed by August.

30 August 1859 was given as the date of the first voyage, but this was later put back to 6 September. The destination was Weymouth, from which a trial trip into the Atlantic would be made. Following this the ship would sail to Holyhead, Wales. The company had made an agreement with the Canada's Grand Trunk Railway to use Portland, Maine as its US destination, and the railway company had built a special jetty to accommodate the ship. William Harrison was appointed Captain in 1856;[citation needed] he drowned on 21 January 1860 while sailing from Hythe to Southampton in the ship's boat.

On 9 September the ship had passed down the Thames, and out into the English Channel, and had just passed Hastings when there was a huge explosion, the forward deck blowing apart with enough force to throw the No. 1 funnel into the air, followed by a rush of escaping steam. Scott Russell and two engineers went below and ordered the steam to be blown off and the engine speed reduced. Five stokers died from being scalded by hot steam, while four or five others were badly injured and one had leapt overboard and had been lost. The accident was discovered to have been caused by a feedwater heater's steam exhaust having been closed, and the explosion's power had been concentrated by the ship's strong bulkheads.

Although designed to carry emigrants on the far Eastern run, the only passenger voyages Great Eastern made were in the Atlantic. Angus Buchanan, an historian of technology comments: "She was designed for the Far Eastern trade, but there was never sufficient traffic to put her into this. Instead, she was used in the transatlantic business, where she could not compete in speed and performance with similar vessels already in service."

Her first voyage to North America began on 17 June 1860, with 35 paying passengers, eight company "dead heads" (non-paying passengers), and 418 crew. Among the passengers were the two journalists and engineers Zerah Colburn and Alexander Lyman Holley as well as three directors of the Great Ship Company. Preparations were initially made for the ship to sail on 16 June 1860 and the passengers boarded her on the 14th. After visitors had been sent ashore the Captain (Capt. John Vine Hall) announced that he would not be sailing until the 17th, as the crew were drunk. Director Daniel Gooch, who was travelling aboard her, was not pleased. He was further displeased by the route taken by the ship which was the more southerly of the regular steamer routes as he had wanted the ship to complete the journey in nine days. In the event, the voyage took 10 days 19 hours.

Upon Great Eastern's return to England, the ship was chartered by the British Government to transport troops to Québec. 2,144 officers and men, 473 women and children, and 200 horses were embarked at Liverpool along with 40 paying passengers. The ship sailed on 25 June 1861 and went at full speed throughout most of the trip arriving at her destination 8 days and 6 hours after leaving Liverpool. Great Eastern stayed for a month and returned to Britain at the beginning of July with 357 paying passengers.

Although the ship had made around £14,000 on its first Atlantic voyage, the Great Ship Company's finances were in a poor state, with their shares dropping in price. They were also threatened with a lawsuit by the Grand Trunk Railway for not making Portland, Maine the ship's port of call as agreed.[18] In addition, Scott Russell had been awarded the sum of £18,000 for repairs following the 1859 explosion. The Company managed to appeal against this but Scott Russell applied to the courts and the Chief Justice found in his favour. The company appealed again, and due to rumours that the ship was about to leave the country, Russell's solicitors took possession of her. The Great Ship Company lost its appeal and had to pay the sum awarded; to cover this and the expenses of a second US voyage, they raised £35,000 using debentures.[19]

Only 100 passengers booked for the second voyage, which was originally scheduled to depart Milford Haven on 1 May 1861. However, the boat taking the passengers to the ship ran aground and they and their luggage had to be rescued by small boats. The voyage took 9 days 13 hours. Great Eastern's arrival in New York was virtually unnoticed due to the American Civil War, and when it was opened to the public at 25 cents a head there was little interest. 194 passengers sailed on the return journey on 25 May and 5,000 tons of wheat was also carried.

Great Eastern sailed from Liverpool on Tuesday 10 September 1861, commanded by Captain James Walker. On her second day out the wind increased to gale force, causing the ship to roll heavily. The port paddle wheel was completely lost, and the starboard paddle wheel smashed to pieces when one of the lifeboats broke loose. At the same time it was discovered that the cast iron rudder post, which was 11 inches (280 mm) in diameter, had sheared off 2 ft (0.61 m) above its collar and the rudder was swinging free and hitting the screw, which was slowly breaking it up.

Captain Walker ordered his officers to say nothing to the passengers concerning the situation, then had a trysail hoisted which was immediately ripped apart by the wind. He then had a four-ton spar thrown overboard secured with a hawser to try to bring some control to the ship, but it only worked for a short while before being torn away. By the end of the second day some of the passengers had an idea as to the predicament they were in and formed a committee chaired by Liverpool shipping merchant George Oakwood. The captain agreed to meet Oakwood and allowed him to inspect the ship. What he found was far worse than had been expected: none of the cargo had been stowed properly and it was all rolling loose in the holds. Hamilton E. Towle, an American civil engineer, who was returning to the States after completing his contract working as a supervising engineer on the Danube River dry-docks in Austria, visited the rudder room and after inspecting the damage came up with a plan to regain control of the rudder. Towle's scheme was taken to the captain, who failed to act on it. In the evening of the third day, Magnet, a brig from Nova Scotia, appeared on the scene. Captain Walker asked her captain if he would stand by. He agreed, but it turned out there was little he could do, and after several hours the brig left, later succeeding in a claim for demurrage from the Great Ship Company for the delay.

Towle now presented his plan to the passengers' committee, and in turn they pressured the captain into letting him try it. Towle had a 100 ft (30 m) chain composed of 60 lb (27 kg) links wound around the rudder post below the break, then secured the ends of the chain to the port and starboard frames of the ship using block and tackle. Two lighter chains were led down from the wheelhouse and attached to the heavy chain and also to the ship's frames. This allowed some limited movement of the rudder, and the ship became steerable again. On the morning of Sunday 15 September the storm finally abated. Towle and the passengers committee insisted that the Captain try the repaired rudder and eventually the engines were started and at 5 pm that day after 75 hours of drifting out of control the ship answered the helm and was turned on to a course towards Ireland, 300 mi (480 km) away.

When the ship arrived at Queenstown, the harbourmaster refused to let her enter because she was not under full control and injured passengers were taken off by boats. The ship had to stand off for three days until she was towed in by HMS Advice. Arrangements for temporary repairs were begun and the passengers were offered free transport to the US aboard other ships. Once the repairs were completed the ship sailed to Milford Haven where permanent repairs were to be carried out. Smaller, 50-foot-diameter (15 m) paddlewheels were fitted, and improvements were made to the steering.

Upon arriving in the US, Towle filed a claim for $100,000 under the laws of salvage, claiming that his efforts had saved the ship. The case was taken to court, and he was awarded the sum of $15,000, quite a considerable sum for that period. Scientific American published an account of the incident and a description of Towle's device. It is uncertain if Towle ever received any of the money awarded to him by the court.

Great Eastern sailed from Milford Haven on 7 May 1862 with 138 passengers, arriving in New York on 17 May. The ship was opened to visitors and around 3,000 a day took the opportunity. The return journey to Liverpool was profitable, with 389 passengers travelling along with 3,000 tons of freight. The west-to-east trip took 9 days 12 hours, a reduction of 12 hours on her previous record.

The second voyage of 1862 saw the ship arriving in New York on 11 July with 376 passengers including the President of Liberia, J. J. Roberts. The return journey later that month carried 500 passengers and 8,000 tons of cargo, the ship arriving at Liverpool on 7 August. Great Eastern left Liverpool on 17 August with 1,530 passengers on board and a substantial amount of freight which increased her draught to 30 ft (9.1 m).

Not wishing to enter New York Bay over Sandy Hook bar due to the ship's deep draught, the captain decided to steam up Long Island Sound and moor at Flushing Bay. The pilot came on board at 1:30 am and the ship moved slowly ahead. At about 2:00 am 1 mile (2 km) east of Montauk, Long Island a rumble was heard and the ship heeled slightly. The pilot said she had probably rubbed against the "North East Ripps" (later renamed "Great Eastern Rock"). The captain sent an officer down to check for damage and he reported no leaks. The ship had a list to port, but made her way into New York the next day under her own steam.

It was discovered that the rock had opened a gash in the ship's outer hull over 9 feet (2.7 m) wide and 83 feet (25 m) long. The enormous size of Great Eastern precluded the use of any drydock repair facility in the US, and the brothers Henry and Edward S. Renwick devised a daring plan to build a watertight, 104 by 15 feet (31.7 by 4.6 m) caisson[22] to cover the gash, held in place by chains around the ship's hull. The brothers claimed that it would take two weeks to complete the repairs and said that they would only take payment if successful. The demands of the American Civil War caused delays in getting the iron plates required, and instead of two weeks the repairs took three months at a cost to the company of £70,000. The ship finally sailed from New York for Liverpool on 6 January 1863.

In 1863 Great Eastern made three voyages to New York, with 2,700 passengers being carried out and 970 back to Britain along with a large tonnage of cargo. One of her paddle wheels was damaged on the last outward trip and she completed it using her screw,[citation needed] while on the return journey she ran down, damaged, and sank Jane, a 775 ton sailing ship, with the loss of two of her 22 crew. It was found that Great Eastern was not maintaining sufficient look-out for the speed she was steaming at; thus she was held to blame for the collision.[24] The company lost nearly £20,000 on the voyages due to a price war between the Cunard and Inman shipping lines, and ended up with debts of more than £142,000, which forced them to lay up Great Eastern.

A plan was mooted to offer the ship in a lottery, which came to nothing, and the ship was finally offered for sale on 14 January 1864 at the Liverpool Exchange, the bidding opening at £50,000. No bids were offered and the ship was withdrawn from sale, the auctioneer declaring that it would be offered for sale with no reserve in three weeks' time.

Meanwhile, Daniel Gooch approached Thomas Brassey and John Pender to see if they would be willing to assist in the purchase of Great Eastern. The opening bid at the auction was £20,000 and John Yates who was acting for Gooch secured the ship for a bid of £25,000, despite the ship being worth £100,000 in materials alone. The three men set up a new company, the Great Eastern Steamship Company, and Great Eastern was chartered to the newly formed Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company for £50,000 of shares, and would be responsible for carrying out the necessary conversion work for the ship's new role, laying the Atlantic Cable.

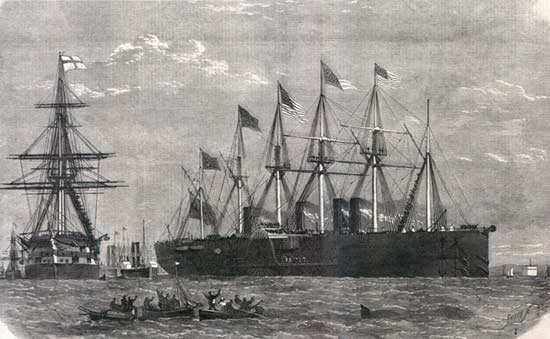

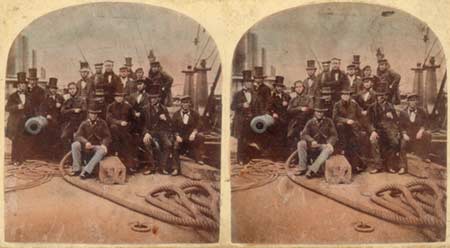

The conversion work for Great Eastern's new role consisted in the removal of funnel no. 4 and some boilers as well as great parts of the passenger rooms and saloons to give way for open top tanks for taking up the coiled cable. Under Sir James Anderson[25] she laid 4,200 kilometres (2,600 mi) of the 1865 transatlantic telegraph cable. Under Captains Anderson and then Robert Halpin, from 1866 to 1878 the ship laid over 48,000 kilometres (30,000 mi) of submarine telegraph cable including from Brest, France to Saint Pierre and Miquelon in 1869, and from Aden to Bombay in 1869 and 1870.

At the end of her cable-laying career she was refitted once again as a liner but once again efforts to make her a commercial success failed. She was used as a showboat, a floating palace/concert hall and gymnasium. She acted as an advertising hoarding—sailing up and down the Mersey for Lewis's Department Store, who at this point were her owners, before being sold. The idea was to attract people to the store by using her as a floating visitor attraction. She was sold at auction in 1888, fetching £16,000 for her value as scrap.

An early example of breaking-up a structure by use of a wrecking ball, she was scrapped at New Ferry on the River Mersey by Henry Bath & Son Ltd in 1889–1890—it took 18 months to take her apart. At the time Everton Football Club were looking for a flagpole for their Anfield ground, and consequently purchased her top mast. It still stands there today at the ground—now owned by Liverpool Football Club, at the Kop end. In 2011, the Channel 4 programme Time Team found geophysical survey evidence to suggest that residual iron parts from the ship's keel and lower structure still reside in the foreshore. During 1859, when Great Eastern was off Portland conducting trials, an explosion aboard blew off one of the funnels. The funnel was salvaged and subsequently purchased by the water company supplying Weymouth and Melcombe Regis in Dorset, UK, and used as a filtering device. It was later transferred to the Bristol Maritime Museum close to Brunel's SS Great Britain then moved to the SS Great Britain museum.

The SS Great Eastern is the subject of the Sting song, "Ballad of the Great Eastern" from the 2013 album The Last Ship. An Atlantic crossing on the SS Great Eastern is the backdrop to Jules Verne's 1871 novel A Floating City The SS Great Eastern and its creator Isambard Kingdom Brunel are central to Howard A. Rodman's 2019 novel The Great Eastern, in which Captain Ahab is pitted against Captain Nemo.

The Eastern Steam Navigation Company was formed in January 1851 with the intention of exploiting the increase in trade and emigration to Australia after the discovery of gold there. To make this a viable proposition they needed a subsidy in the form of a mail contract from the GPO, for which they tendered. In March 1852, against the advice of a House of Commons Committee set up to look into the awarding of mail contracts, the Government awarded both to P&O, although the ESN tender was lower.

Finding themselves in the position of having a company without a purpose, they were in effect open to offers. Brunel wrote a paper on his idea of building a ship capable of sailing to and from Australia without the need to refuel on route and sent it to ESN. He was invited to present his ideas to the board but was unable to attend so John Scott Russell took his place. A committee was set up to look into the idea and they reported in favour and the scheme was adopted at a board meeting held in July 1852. Brunel was appointed Engineer and tenders were invited for the hull, paddle engines and screw engines.

However, although the board had accepted the scheme in principle, a number of the directors and the chairman resigned. Brunel approached Henry Thomas Hope to become the new chairman and with his help and that of John Yates, the company secretary, they were able to fill the vacancies on the board. Now Brunel, Charles Geach and John Yates set about raising capital by placing 40,000 shares of £20 each with interested investors. The first call on the shares was £3 raising a working capital of £120,000. All this was achieved by December 1853.

THE CONTRACT

The final contract signed by Scott Russell on 22 December 1853 laid down the following terms.

Provided for the construction, trial, launch and delivery of an iron ship of the general dimensions of 680 feet between perpendiculars, 83 feet beam and 58 feet deep according to the drawings annexed, signed by the engineer, I. K. Brunel.

All vertical joints to be butt joints and to be double riveted wherever required by the engineer. Bulkheads to be at 60 feet intervals. No cast iron to be used anywhere except for slide valves and cocks without special permission of the engineer. The water tightness of every part to be tested before launching, the several compartments to be filled one at a time up to the level of the lower deck.

The ship to be built in a dock.

After the launch such trials and trial trips at sea will be made with the engines and probably under sail as in the opinion of the engineer may be necessary to ascertain the efficiency of the work. Any defects then discovered in workmanship or quality of materials to be forthwith remedied by, or at the expense of, the contractor to the satisfaction of the engineer.

All calculations, drawings, models and templates which the contractor may prepare shall from time to time be submitted to the Engineer for his revision and alteration or approval. The Engineer to have entire control over the proceedings and the workmanship.

CONSTRUCTION

As the pile driving was being carried out a moulding floor was being constructed and roofed, so that the ship’s lines could be laid out in full scale. New plate bending and punching machines were installed in Russell’s yard. Coffer dams were sunk in the floor for the paddle engine cylinders to be cast. To be able to build the paddle engine a new workshop had to be erected as the engine, when completed, stood 40 feet high.

The ship was to be double hulled with transverse bulkheads spaced at 60 feet intervals. These were built to a height of 5 feet above the deep loadline. Two longitudinal bulkheads spaced 36 feet apart ran the full 350 feet of the two engine rooms. These also reached up to the loadline. Two tunnels were installed at the lowest level, one carried the steam pipes while the other provided a link between the two engine rooms.

The first problem to arise was where the ship was to be built. Russell’s contract stipulated that it was to be built in a dock, Russell quoted a price of £8-10,000 to build the dock and so this part of the scheme was abandoned partly on the grounds of cost and partly on the need to find a suitable site on which to build the dock. Also the idea of a normal launch, ie stern first, was also rejected because of the length of the vessel and to provide the right launch angle the base of the ship, at the bows, would be 40 feet in the air. Eventually it was decided to build the ship parallel to the river and use a mechanical patent slip, designed by Brunel, for the launch. Later this scheme was also dropped on the grounds of cost.

Having decided on a sideways launch, a suitable site had to be found, Russell’s yard being too small. The adjacent yard belonging to David Napier, was empty, available and suitable so it was leased. As the punching machines and plate rollers were installed in Russell’s yard a railway was laid between the two yards for moving materials.

The keel plate was laid in May 1854 and it was expected that construction of the hull and engines would be completed by October 1855. Attached to the keel plate was the centre web which in turn had horizontal plates attached. 1 inch thick plates were used, on both inner and outer hulls, for eighteen feet either side of the centre web, these were flat to enable the ship to be beached on a gridiron. At the time no drydock existed that would be able to accommodate the ship.

The transverse and longitudinal bulkheads built of ½ inch thick plates, were attached to the centre web, and were, like the rest of the ship built up plate by plate. Then the longitudinal bulkheads were built up the same way. The deck was constructed of ½ inch plates in the same way as the hull two layers of plates being used. The deck was then covered with timber to produce a level surface.

Plating the hull, using ¾ inch thick plates throughout, began with the inner hull. The hull plates were built of inner and outer strakes, the second strake would be riveted to the inside of the first and third strake, the fourth to the inside of the third and fifth and so on. Longitudinals which consisted of normal sized plates, ½ inch thick, with 4½ inch angle iron riveted to both of the long sides, were riveted to the inner hull and then as the outer hull was plated the longitudinals would be attached. They were riveted to the centre of the inner and outer hull plates and were attached to every other row, with the exception of the flat plates on the bottom where they were attached to every row. With the angle irons overhanging half an inch the space between the hulls was 2 feet 10 inches. The height between each row of longitudinals was 5 feet 6 inches. All of the inner surfaces of the two hulls were painted to reduce corrosion.

In November 1854 Charles Geach suddenly died. As well as being a Director of the ESN he was also a Director of Beale and Company who were to supply the plates for the ship. He had agreed to take a large part of the payments from Russell in shares of ESN., Russell himself receiving part payment in ESN shares.

The first indication of the problems to come appeared on New Year’s Day 1855 when Russell informed Brunel that he was in financial difficulty and his bankers had refused him further credit. Brunel approached the board and it was agreed that Russell would be paid the amount due to him on his contract in instalments of £8,000 subject to agreement that the necessary work had been completed. This satisfied Martin’s Bank, who were Russell’s main creditors, at least for the time being.

On 12 October 1855 Russell again contacted Brunel to inform him that his bankers required an immediate payment of £12,000 on his £15,000 overdraft. Brunel authorised a payment of £10,000. A week later Russell again got in touch with Brunel to say that his bankers wanted the £15,000 and would not be satisfied with the offer of £10,000. Russell made the point that he was employing a large number of men and he needed the money to pay their wages, or he would have to lay them off. Although true quite a number of these men were employed on other ships being built by Russell and not on the Great Eastern. In all Russell had laid down six ships, some of them in Napier’s yard, one of which was preventing the completion of the stern of the Great Eastern.

|

1856 Progress of the Great Ship, Building at |

At the beginning of February 1856 Brunel advised the Company to take possession of the ship, citing breach of contract, to avoid its sequestration by Russell’s creditors. This produced a reaction from Russell’s bankers who refused to honour his cheques and foreclosed on his assets. On 4 February Russell suspended all payments to his creditors and a week later dismissed all his workmen.

A meeting was held by Russell’s creditors on 12 February at which it was disclosed that Russell had liabilities of £122,940 and assets of £100,353. It was decided that existing contracts would be allowed to run to completion and the business would be liquidated under the supervision of three inspectors appointed by his creditors. To the board of the ESN he issued a statement, in which he repudiated his contract effectively handing the uncompleted ship back to the company. This was from the man who had received a total of £292,295 including extra payments for additional work from ESN and yet when the situation was reviewed it was found that three quarters of the work on the hull had not been completed and there was a deficiency of 1200 tons in the amount of iron supplied and that used on the ship. Out of the original estimate for the construction of the hull only £40,000 had not been paid to Russell.

As all this was happening Brunel wrote to John Yates at Milwall instructing him to negotiate with Russell for the lease of his yard and equipment. Yates wrote back to say that Russell had mortgaged the yard to his banker and that any negotiation would have to be with the bank, who, after weeks of wrangling, agreed to lease the yard and equipment until 12 August 1857.

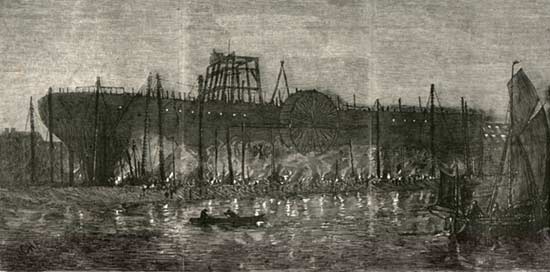

|

1857 Working on the “Great Eastern” by Gaslight |

The ESN began the task of getting the work completed, those that had worked on the ship stuck out for the best deal they could get and the company had little option but to pay. Replacing the former workers was not a viable option and of course Russell’s assistants held the plans and drawings of the ship. Work on the ship restarted in May and it took far longer to complete than was expected. Towards the end of June 1857 Brunel reported that once the screw, screw shaft and the sternpost had been installed the ship would be ready for launching by the end of July. The only problem was that because of Russell’s opposition to a sideways launch and then the problems of accessing the site, the launch ways and cradles would not be ready in time. The contract for their construction had only been placed, with railway contractor Thomas Treadwell, in January 1857. Brunel then wrote to company secretary Yates to negotiate an extension of the lease on Russell’s yard. After protracted negotiations the mortgagees agreed to an extension from 12 August to 10 October for the sum of £2,500.

On the due date the mortgagees took possession of the yard and refused entry to all the workmen. Under pressure from all sides and against his better judgement Brunel agreed to launch the ship on 3 November.

THE IRON PLATES

The plates used were of a standard size 10 feet 0 inches by 2 feet 9 inches, those used on the bottom were 1 inch. thick those on the sides ¾ inch thick and those on the deck and bulkheads were ½ inch. thick. In all 30,000 plates were used and these were supplied by Beale & Company, Parkgate Ironworks, Rotherham, Yorkshire. Each plate was shaped by hand rollers and cut where necessary with steam operated shears, the form or line being taken from wooden models of the hull. Each plate was marked and numbered on the model and this was then painted on the relevant plate by a boy who also marked out the rivet holes, each plate requiring 100 rivets, according to another template. The rivet holes were then punched out with a steam operated punch. The plate would then be manhandled onto a bogie and moved on rails to where it was needed and would be hauled into place by men using a block and tackle.

RIVETING GANG

At the peak of the building around 200 riveting gangs were at work on the ship, working a minimum of 12 hours per day. A riveting gang consisted of two riveters or ‘bashers’ as they were known, a ‘holder on’ and two boys. One boy heated the rivets the other caught the white hot rivet, thrown to him by the first boy, he then placed it in the relevant hole, the holder on then kept the head of the rivet tight up against the inside of the plate while the bashers, striking alternately, hammered the other end into shape. One such gang could fit 400 rivets per day. When the outer hull was being riveted the holder on and the second boy worked between the two hulls in a space just 2 ft.10 inches wide.

PADDLE ENGINES

The paddle engines were built by John Scott Russell on site. They were oscillating engines with four cylinders each 74 inches in diameter and a 14 foot stroke. The cylinders could be worked in pairs or altogether, a friction clutch being provided to enable the connection or disconnection of either pair.

The crankshaft was manufactured by Messrs Fulton & Neilson, Lancefield Forge, Glasgow, who had to build new furnaces, to produce sufficient steel at one time, to make the casting. The first two attempts failed but success came with the third. It weighed 40 tons and the company charged a fee £100 per ton. In addition the forge also manufactured the following;

Two paddle cranks, two paddle shafts, intermediate crankshaft and the two friction shafts.

Construction of the engines took about twelve months and they were assembled in Russell’s yard and then dismantled and fitted into the ship, partly before launch and the rest including the main crankshaft shaft were installed during fitting out. In October 1854 Russell wrote to Brunel that he was about to cast the last cylinder and asked if Brunel would come to see it done. Of the other three cylinders two had been bored and faced and the third was in the process of being bored. Each cylinder casting used 34 tons of iron.

|

Promotional book |

PADDLES

The paddles were 56 feet in diameter and these could be reefed or shortened to 36 feet to suit the draught of the ship. Each paddle had thirty 13 ft by 3 ft floats fitted. During a later refit the paddles were reduced to a diameter of 50 feet.

SCREW ENGINES

The screw engines designed and built by James Watt & Company at their Soho Works in Birmingham were direct slide guide engines working with a single and double connecting rod, each pair working one crank. They consisted of four cylinders horizontally opposed, each 7 feet in diameter with a 4 foot stroke. The first cylinder was cast in August 1854 and Brunel was invited to witness the event.

SCREW SHAFT

The screw shaft was 2 feet in diameter and consisted of four coupled shafts each 30 feet long and a tail shaft 40 feet long. The tail shaft was manufactured at the Lancefield Forge, the rest being made in London. The tail shaft was supported by a bearing consisting of four blocks of wrought iron 8 feet by 16 inches which were lined with Babbit. After the maiden voyage it was found that the Babbit had been squeezed out at the bottom of the bearing. The lower sections of the bearing were planed back by 2 inches and a brass lining with dovetail grooves cut into it was fitted. The grooves were lined with lignum vitae.

PROPELLER

The propeller was made of cast iron, fitted with four blades, giving it a diameter of 24 feet and 44 feet pitch. Each blade was fixed to the 8 feet diameter boss by 12 bolts each of 2 ½ inches diameter. The total weight being 36 tons.

STEERING

When built Great Eastern was fitted with manual steering. Two wheels were fitted to the same axle and these moved the tiller by means of chains. Later two more wheels were added and provision made for four more. In bad weather with all wheels manned problems still occurred.

In 1867 during the fitting out for the Paris Exhibition, steam powered steering gear designed by John McFarlane, a steam engineer, who was Engineer Surveyor to the Board of Trade in Belfast, was installed.

THE LAUNCH WAYS

Around a thousand wooden piles, each thirty feet long, were driven into the ground to form the base on which to build the ship. On top of these timber baulks were laid to form a bed for the keel. The ways themselves each consisted of a 2 feet thick bed of concrete onto which were bolted 1 foot square timber baulks fixed parallel to the ship. The spaces between these timbers was filled with concrete. Further timbers were laid at right angles to the ship and then a final layer again parallel to the ship onto which were laid standard railway lines running at right angles to the ship.

The remains of the ways can still be seen at Millwall; there is a commemorative plaque on the riverside walk.

At one time there was also a large sign along the river bank, but this has long since disappeared.

THE LAUNCH

For the launch the ship was supported by two cradles each 120 feet wide, shod with 1 inch iron bars. These cradles were 110 feet apart and the bow and stern overhung them by 180 feet and 150 feet respectively. During the latter part of October between 1,000 and 1,500 men worked day and night to remove everything not required for the launch.

Brunel now realised that he would be unable to test all the various items of equipment before the launch. The lease of the shipyard cost £1,000 a month and everyone was pressing for a launch date. So at the end of October he settled on 3 November 1857 to catch the high tide.

|

Child’s souvenir alphabet |

Brunel had hoped to undertake the launch with the minimum of publicity but word had spread and many thousands of spectators had manned every vantage point around the yard. In his preparations for the launch he had requested that the men be told to keep quiet during the launch and any verbal orders be given quietly but firmly. He would give his orders by means of signal flags from the launching platform at the top of the ships side. To his dismay he found out that the directors had sold 3,000 tickets permitting spectators to enter the yard. As he was getting ready some of the directors joined him on the rostrum with a list of names. Brunel’s reply on being asked which he preferred was “Call her Tom Thumb if you like.” At 12.30 pm the daughter of Henry Thomas Hope, Chairman of the ESN, christened the ship Leviathan.

3 November. At the first attempt the forward cradle moves 3-4 feet in two seconds, then stops. The after cradle slides about 6 feet and stops. The latter took up the slack on the checking chain and the windlass spun rapidly throwing the men sitting on it into the air. One of them, died from his injuries a few days after the accident. A second attempt was abandoned when teeth on the forward winch were stripped followed by a pin breaking in one of the rams.

19 November. Another attempt but the abutments for the rams failed.

|

Attempting to launch the Great Eastern |

28 November. The ship begins moving at a rate of about one inch a minute. Following a break for dinner the ship refused to move. It was found that the rails had sunk into the timber and the cradles were lying in small hollows. Two of the four midship barges broke their mooring chains and so the attempt was abandoned. The ship had moved a further14 feet closer to the Thames.

29 November. The broken chains were repaired overnight, but the same problem occurred. The chain attached to the stern dragged a 15 ton block of concrete, used to moor it, across the river bed and under the stern of the ship. Unable to move the ship with existing equipment Brunel begged and borrowed equipment from the surrounding area and with this succeeded in moving the Great Eastern another 8 feet.

30 November. Moved about 8½ feet before a 10 inch jack on the forward cradle failed. Two extra hydraulic jacks were added to each cradle and the moorings for the barges were strengthened. The ship moved a further 14 feet. Around 200 spectators watching events from staging erected outside the yard fell 20 feet when it collapsed, many were hurt, seven seriously, but no one was killed.

3 December. A further 14 feet closer to launch.

4 December. The ship moves another 14 feet before two rams, one 14 inch and one 7 inch, failed and with that all attempts were abandoned for the day.

5 December. Visit from Princess Royal, the Duchess of Atholl, Marquis of Stafford and Sir Joseph Paxton (designer of the Crystal Palace). Another 14 feet. New abutments for the rams had to be built as the existing ones were 60 feet away from the cradles.

7 December. The water supply pipes of two rams failed and nothing was done until the afternoon when the ship was encouraged to slide a further 8 feet. Mooring tackle of the haulage gear gave way.

16 December. Moved a further 3 feet. Much of the equipment, rams, chains etc. failed during the day. Brunel was accompanied by Robert Stephenson, himself in poor health, but there to help his friend in anyway he could.

After this attempt Brunel and Stephenson agreed that more hydraulic rams were needed to finish the job. Brunel dispatched one of his assistants to Richard Tangye’s workshop in Birmingham with an order for more presses. With the equipment supplied by Tangye’s doing the work, the company slogan became, ‘We launched the Great Eastern and the Great Eastern launched us.’

4 January 1858. New abutments had been built, requiring the breaking up of the concrete underlying the ways. New rams were obtained from Tangye’s including the 21 inch one used by Stephenson to raise the Britannia bridge. The haulage gear was more securely fixed to the Deptford side of the river. A barque running upstream collided with one of the barges and sank it.

5 and 6 January. The ship moved 10 feet each day and at the same time was squared up on the ways ready for the next attempt.

10 January. Reached a point where at high tide she was partially afloat.

11 to 14 January. Gradually pushed down the ways until Brunel ceased operations to prevent her floating off on the high tide of the 19th. Water was pumped into the twin hull to prevent the ship launching itself.

20 January. Following the high tide the ship was pushed into position ready for launch which was set for the 30 January.

30 January. The weather was too windy and the launch was postponed until the following day.

31 January. Throughout the night the water ballast was pumped out of the ship and at 1.30 pm the ship was finally afloat. Four steam tugs, Victoria and Pride of all Nations at the bow, with Napoleon and Perseverance at the stern gently moved the Great Eastern to the Deptford side of the river where she would be fitted out. As this was going on a barge fouled the starboard paddle wheel and Captain Harrison ordered it to be sunk.

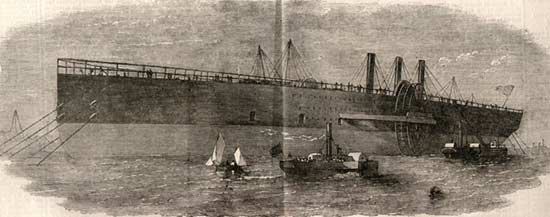

|

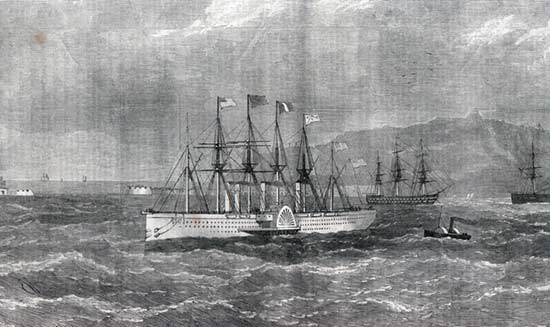

The “Great Eastern” at her Moorings |

FITTING OUT

The launch had cost £170,000, one third of Brunel’s estimate for the whole ship, and it still had to be fitted out. Getting any more money out of the ESN shareholders proved more difficult than getting the ship into the Thames. The Eastern Steam Navigation Company was close to bankruptcy and to prevent this happening and creditors seizing the ship a new company the ‘Great Ship Company’ was formed with a capital of £340,000. They bought the Great Eastern for £160,000, leaving sufficient funds for the fitting out. Existing ESN shareholders were given the market value of their £20 shares, £2-10s (£2.50), towards payment for shares in the new company and then the Eastern Steam Navigation Company went into liquidation.

|

Tenders were invited and two were received, one from Wigram and Lucas for £142,000 and the other from John Scott Russell for £125,000. Brunel had been told by his doctor to take a long holiday and he was absent during the time that the fitting out contract was awarded to Russell. Russell’s tender was accepted and in January 1859 the work was started. The terms of the contract being that the work was to be completed in six months to enable the ship’s first voyage to America to take place that summer.

Russell at this point was only responsible for the completion of the paddle and auxiliary engines and supervising the various sub-contractors he had been engaged to carry out the variety of tasks involved.

The following is a contemporary account of the fitting out of the passenger accommodation:

Running crosswise are twelve watertight bulkheads or walls, extending the entire height to the upper deck, with no openings below the lower deck: the ship is thus cut off into ten or more compartments, generally about 60ft long. Five of the compartments near the centre of the ship form five complete hotels for passengers, each comprising upper and lower saloons, bedrooms, bar, offices, etc and each cut off from the others by the iron bulkheads. It is as if five hotels, each measuring about 80 ft x 60 ft and 25 ft high, were let down into an equal number of vast iron boxes. Vertical longitudinal walls separate each compartment into central saloons and side cabins, or bedrooms, and decks separate the height into two such series of rooms.