The first recorded documentary evidence of the existence of pheasants is in the year 1059 in relation to an order of King Harold. Although mentioned, it is not thought that they were widely distributed at this stage and Normans passed laws to ensure they were protected. These laws allowed the pheasant population to increase significantly and by 1100, Henry I granted the Abbot of Amesbury the right to kill pheasants. It was not until practical hand-held firearms arrived in Britain around 1500 that shooting pheasant for sport really took off. Henry VIII is known to have enjoyed shooting and had a French priest appointed as a ‘fesaunt breeder’. Since this time, pheasant shooting has continued to be a popular Royal pastime.

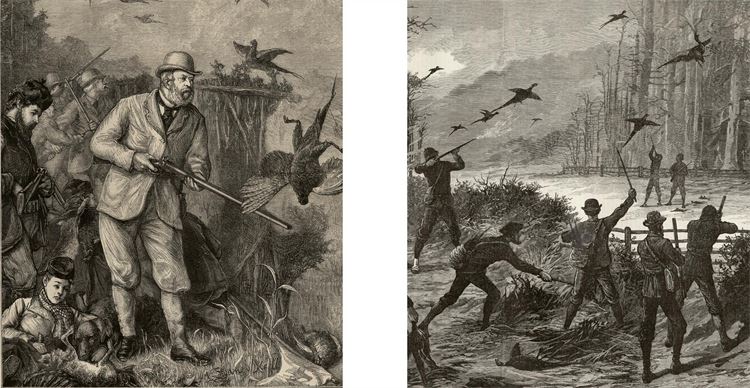

Until the late 17th Century, birds were shot when stationary on the ground or perched. By the 18th Century, significant improvements in shotgun technology had been made and with the introduction of the double barrelled breech loading gun in the mid 19th Century saw the development of the driven shoot. A new concept at the time, instead of walking towards the birds, these shoots were formally organised with the guns at a fixed position or pegs whilst the birds were driven towards them. This technique, as we use today allows for more challenge with a variety of high flying birds and the Keeper able to control the amount and general direction of the birds.

heasant shooting has been taking place in Great Britain since the 16th century, albeit on a relatively small scale prior to the mid-19th century when the advent of the breech loading shotgun, which enabled sportsmen to kill a large amount of gamebirds within a relatively short period, paved the way for the development of the driven shoot. Prior to this time, pheasants were usually walked-up over dogs and shot in small numbers, with little artificial rearing taking place. Indeed, wild pheasants were quite scarce in many areas, despite being preserved by gamekeepers through nest management, vermin control and poaching prevention. Before the pheasant became a fashionable quarry species, the grey (or ‘common’) partridge, then found in large numbers in some parts of the country, was the principal gamebird pursued by sportsmen, either by shooting, by netting or by hawking.

The sport of pheasant shooting did not really start to become popular until the Regency period following the invention of the percussion cap gun, a much more efficient weapon than the old flintlock gun, which enabled bigger bags of game to be shot. Landowners were now planting woods and coverts on their property, not only to create aesthetically pleasing landscapes but for foxhunting purposes and with pheasant shooting in mind.

By the 1820s, the Continental practice of ‘battue’ or driven game shooting had begun to take place on a few well-known English estates, including Knowsley in Lancashire, where a total of 27,000 head of game were killed in 1825, and at Eaton Hall in Cheshire, where the 1st Marquess of Westminster was already artificially rearing pheasants to bolster rapidly dwindling stocks of wild birds. The largest bag taken on a battue at this time, shot over a period of three days at Ashridge Park in Hertfordshire in January, 1822, amounted to 1,200 head of game.

In 1831, King William IV passed a landmark Game Act which removed the property qualification for killing game, enabling any purchaser of a game certificate to go out in pursuit of game on a farm or estate provided that he had the owner’s permission to do so. This legislation led not only to a massive increase in game shooting, game preservation and in gun ownership, but also established a statutory shooting season for pheasants running from October 1 to February 1.

Walked-up shooting, however, continued to be the principal form of game shooting practised in Britain throughout the 1830s. Pheasants were still relatively scarce in some districts at this time, with partridges, hares and rabbits forming the major portion of the bag taken by many sportsmen.

Indeed, battue or driven game shooting remained a minority sport until 1840 when Queen Victoria married Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. The Prince, a keen sportsman who was used to the large-scale shoots held in his German homeland, immediately set about popularising driven game shooting in his adopted country and turned the royal estate at Windsor into a massive game preserve suitable for entertaining important guests, planting woods and coverts, rearing pheasants, putting down imported live hares and acquiring additional sporting rights over nearby Bagshot Park.

Wealthy sportsmen, particularly younger men, soon began to follow the royal example, establishing driven shoots – often in the hope of attracting Prince Albert and winning a coveted invitation to shoot at Windsor. By the mid-1840s the Prince was regularly visiting English estates to shoot pheasants in late autumn after returning from his annual deer stalking expedition in Scotland. In 1846, while staying with the Marquess of Salisbury at Hatfield in Hertfordshire, he created a new record on a driven shoot killing 150 head of game in 150 minutes, shooting with four guns!

The introduction of the breech-loading shotgun in the mid-1850s, which enabled sportsmen to kill large numbers of pheasants and partridges within a relatively short space of time, gave another boost to driven game shooting. Many of the more traditional sportsmen who espoused walked-up shooting now switched to the driven method and started to artificially rear pheasants and plant game-friendly woods and coverts.

Over the next two decades, Edward, Prince of Wales, the eldest son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, actively promoted driven pheasant and partridge shooting amongst the elite of society, particularly after he had purchased the Sandringham Estate in Norfolk in order to pursue his interest in the sport. Within a very short space of time, shooting took priority over agriculture in many parts of the British Isles. Large numbers of gamekeepers were recruited to rear pheasants and partridges, foresters were employed to manage areas of woodland, and armies of farm workers were given the chance to earn extra money as beaters on shoot days.

By 1875, driven pheasant shooting had become firmly established as the leading fieldsport, not only throughout much of England and Wales but also on many Scottish and Irish estates. Virtually every major landowner was now striving to build up a shoot which provided daily bags of between 500 and 1,000 pheasants, usually in the hope of attracting top Shots such as the Marquess of Ripon, Lord Walsingham, the Maharajah Duleep Singh, or even Edward, Prince of Wales!

Throughout the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, driven pheasant shooting was an important fixture on the social calendar on most large estates. Edward, Prince of Wales, who ascended the throne as King Edward VII in 1902, dominated the world of shooting at this time, and made an annual ‘progress’ around top shoots such as Chatsworth, Eaton, Elveden and Holkham right up until the time of his death in 1910.

Driven pheasant shooting continued to take place on a grand scale until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. In fact, in the last full season before the war, 1913, a party of seven Guns headed by King George V took an all-time record bag of 3,937 pheasants at a battue held on December 18 of that year at Hall Barn in Buckinghamshire, seat of Lord Burnham, the then proprietor of The Daily Telegraph. This event has been described as the high point of the big shoot era.

Sadly, punitive taxation imposed by the Lloyd George Liberal government following the cessation of hostilities in 1918 meant that a large number of top driven pheasant shoots in Great Britain were obliged to make drastic economies in order to survive, with a resultant decline in the size of bags taken. However, a few of the great shoots, such as those owned by the royal family, the Duke of Westminster, the Duke of Rutland and a minority of other wealthy landowners, continued to operate along Edwardian lines until the declaration of the Second World War in 1939, when shooting for sporting purposes was discontinued for the duration of the war on virtually every estate in the land.

Gamebird rearing restrictions enacted by the Labour government in the wake of the Second World War prevented landowners from re-building driven pheasant shoots until the mid-1950s, when economic constraints, in particular high labour costs, necessitated the introduction of ‘let days’ on many estates, or sporting leases whereby a shoot was let out to a syndicate of Guns who were usually responsible for all management costs.

From the 1960s onwards, there was a resurgence in the interest in large-scale driven pheasant shooting, particularly on English estates where landowners or syndicate tenants revitalised well known shoots, often taking advantage of modern pheasant rearing methods rather than producing birds using the traditional ‘broody hen’ incubation system, or by purchasing stock from game farms.

For example, Harry Grass created the world class Broadlands pheasant shoot in the Test Valley in Hampshire for Earl Mountbatten of Burma, a member of the royal family, who used the shoot to entertain both British and European royals, as well as leading international businessmen such as Henry Ford II and Sir Thomas Sopwith. Grass, known as the ‘King of the Gamekeepers’, raised the daily pheasant bag taken at Broadlands from 703 birds on December 19, 1959 to a record-breaking 2,139 on November 28, 1970 – one of the largest daily bags shot in Britain since 1913.

Less than a decade after Harry Grass set to work improving the Broadlands pheasant shoot, David Hitchens, a Wiltshire farmer, began to develop what is now the internationally famous Gurston Down shoot, some 30 miles distant from Broadlands, concentrating specifically on providing high pheasants for wealthy, paying Guns. Several shoot owners in the south-west of England subsequently followed in Hitchens’ footsteps, creating commercial high pheasant shoots on Exmoor, most notably Miltons, Molland and Castle Hill.

The interest and enthusiasm for pheasant shooting, both driven and walked-up, has continued to gather momentum in the United Kingdom over the past 40 years or so, with a wide variety of shoots located throughout England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, ranging from large driven shoots on great estates to tiny walked-up shoots on Scottish offshore islands. Further, during this period the sport of pheasant shooting has become much more democratic, no longer being the preserve of the rich and the famous, but also available to the working man through the medium of the ‘self-keepered’ shoot whereby a group of friends rent land from a farmer or an estate and manage their own small shoot.

Today, the great majority of driven pheasant shoots in the United Kingdom are run along commercial lines, primarily for the benefit of paying Guns, both private and corporate. Many of the smaller walked-up pheasant shoots are operated on a business footing, too, letting days out to private clients in order to help defray some of the running costs.

According to a number of recent surveys, the British game shooting industry is currently worth between £2billion and £2.5billion to the economy. However, the famous old saying ‘Up goes a guinea, bang goes a penny halfpenny, and down comes half-a-crown’, which refers to the cost of rearing a pheasant, the cost of a cartridge, and the price paid by a game dealer for a dead bird at the end of a shoot, is as relevant today as it was a century or so ago during the Edwardian era, especially now that it can cost as much as £50 to put a pheasant in the air, with an expected return of less than 50p – if anything at all – for a dead bird!

For an artist of such ability, popularity and wide output, information about Samuel Jones is comparatively scarce. Living in London, the first recorded mention of him was as an exhibitor at the Royal Academy in 1820 with a picture of an old mare, which he later exhibited at the British Institute in 1824.

Jones is best known for the fine quality of his sporting pictures, mainly portraits of hunting and work horses. In addition, he painted coaching, shooting, fishing, (an example of this being in the collection at Hutchinson House), and hunting scenes, paying much attention to the background landscapes. He also painted historical scenes and portraiture. His landscape works, often featuring cattle, were usually of views in Derbyshire, Kent, Sussex, Essex and Wales. Some of these were of substantial size and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London as a number of landscape sketches in its collection.

From notes made in two of his sketch books to be found in the British Museum, it can be seen that Jones thought that landscape painting was very important. This is reflected in the handling of trees and shrubs in his paintings. Wood, in his Dictionary of Animal Painters, says of him, “His landscape, by itself or as a setting for his sporting figures, is well-painted and commands

respect, being far superior to that of most animal painters, amongst whom he can hardly be numbered”.

His works were much engraved and published, the last being in 1849, and these were produced by Charles and George Hunt, Fellows, Hineley, Pyall and Smart.

Jones exhibited fourteen works at the British Institute, including views of watermills in Derbyshire and Kent. A further fourteen of his works were displayed at The Royal Academy including titles such as ‘The Lesson,” “Delightful Task” and “Born to Good Luck.” He also exhibited nineteen paintings at the Royal Society of British Artists in Suffolk Street.

He had two sons, Paul and Charles, who both became well-known landscape and animal painters

Bibliography

Dictionary of British Equestrian Artists - Sally Mitchell

A Dictionary of Artists 1760-1893 - Algernon Graves

Dictionary of British Landscape Painters - M H Grant

A Dictionary of British Animal Painters – J C Wood

Dictionary of Victorian Painters – Christopher Wood

Dog Painting 1840-1940 – William Secord