inscribed an dated in the margin "Saltburn 1865" and signed with initials "TT"

Tom and Laura Taylor and thence by descent

Saltburn-by-the-Sea, commonly referred to as Saltburn, is a seaside town in Redcar and Cleveland, North Yorkshire, England, around 26 miles (42 km) south-east of Hartlepool and southeast of Redcar.

It lies within the historic boundaries of the North Riding of Yorkshire. It had a population of 5,958 in 2011.

The development of Middlesbrough and Saltburn was driven by the discovery of ironstone in the Cleveland Hills and the building of two railways to transport the minerals.

Old Saltburn is the original settlement, located in the Saltburn Gill. Records are scarce on its origins, but it was a centre for smugglers, and publican John Andrew is referred to as 'king of smugglers'.

In 1856, the hamlet consisted of the Ship Inn and a row of houses, occupied by farmers and fishermen. In the mid-18th century, authors Laurence Sterne and John Hall-Stevenson enjoyed racing chariots on the sands at Saltburn.

The Pease family of Darlington developed Middlesbrough as an industrial centre and, after discovery of iron stone, the Stockton & Darlington Railway and the West Hartlepool Harbour and Railway Company developed routes into East Cleveland. By 1861, the S&DR reached Saltburn with the intention of continuing to Brotton, Skinningrove and Loftus; but the WHH&RCo had already developed tracks in the area, leaving little point in extending the S&DR tracks further.

In 1858, while walking along the coast path towards Old Saltburn to visit his brother Joseph in Marske-by-the-Sea, Henry Pease saw "a prophetic vision of a town arising on the cliff and the quiet, unfrequented and sheltered glen turned into a lovely garden".

The Pease family owned Middlesbrough Estate and had control of the S&DR, and agreed to develop Henry's vision by forming the Saltburn Improvement Company (SIC). Land was purchased from the Earl of Zetland, and the company commissioned surveyor George Dickinson to lay out what became an interpretation of a gridiron street layout, although this was interrupted by the railway which ran through the site. With as many houses as possible having sea views, the so-called "Jewel streets" along the seafront—Coral, Garnet, Ruby, Emerald, Pearl, Diamond and Amber Streets, said to be a legacy of Henry's vision, were additional to the grid pattern.

After securing the best positions for development by the SIC, money was raised for construction by selling plots to private developers and investors. Most buildings are constructed using 'Pease' brick, transported from Darlington by the S&DR, with the name Pease set into the brick. The jewel in Henry Pease's crown is said to have been The Zetland Hotel with a private platform, one of the world's earliest railway hotels.

The parcel of land known as Clifton Villas was sold by the SIC in 1865 to William Morley from London who built the property, 'The Cottage' (now Teddy's Nook) on a site originally intended for three villas. The SIC stipulated in the deed of covenant that "any trees planted along Britannia Terrace (now Marine Parade) were not to exceed 1' 6" above the footpath" (46 cm) to preserve sea views for Britannia Terrace residents and visitors.

The Redcar to Saltburn Railway opened in 1861 as an extension of the Middlesbrough to Redcar Railway of 1846.The line was extended to Whitby as part of the Whitby Redcar and Middlesbrough Union Railway.

The coastline at Saltburn lies practically east–west, and along much of it runs Marine Parade. To the east of the town is the imposing Hunt Cliff, topped by Warsett Hill at 166 metres (545 ft). Skelton Beck runs through the wooded Valley Gardens in Saltburn, then alongside Saltburn Miniature Railway before being joined by Saltburn Gill going under the A174 road bridge and entering the North Sea across the sandy beach. The A174 road number is now used for the Skelton/Brotton Bypass.

-

Road down the bank

-

Cat Nab (left foreground) and Hunt Cliff

-

Esplanade and sea wall

-

Skelton Beck and Saltburn Bridge

-

The community theatre on the right

A forest walk in the Valley Gardens gives access to the Italian Gardens and leads on to the railway viaduct. On the shore of Old Saltburn stands the Ship Inn, which dates to the 17th century. In the town there are plenty of Victorian buildings. There is also a thriving local theatre, The 53 Society, and a public library.

Main article: Saltburn Cliff Lift

The Saltburn Cliff Lift is one of the world's oldest water-powered funiculars—the oldest being the Bom Jesus funicular in Braga, Portugal. After the opening of Saltburn Pier in 1869, it was concluded that the steep cliff walk was deterring people from walking from the town to the pier. After the company was taken over by Middlesbrough Estates in 1883, they discovered that the wooden Cliff Hoist had a number of rotten supports.

The Saltburn tramway, as it is also known, was developed by Sir Richard Tangye's company, whose chief engineer was George Croydon Marks. The cliff tramway opened a year later and provided transport between the pier and the town. The railway is water-balanced and since 1924 the water pump has been electrically operated. The first major maintenance was carried out in 1998, when the main winding wheel was replaced and a new braking system was installed.

Main article: Saltburn Pier

Saltburn's attractions include a Grade II* renovated pier, the only pleasure pier on the whole of the Northeast and Yorkshire coast.

The Saltburn Miniature Railway is a 15 in (381 mm) gauge railway that runs south from Cat Nab Station close to the beach, for about ½ mile inland to Forest Halt, where there is a woodland walk and the Italian Gardens.

As the town had been founded by Quakers, the SIC had a ban on public houses. Alcohol was served in the hotels and the bars attached to them, and in private members' clubs, which included; Ruby Street Social Club (formerly The British Legion; now demolished), Lune Street Social Club (Top Club), Milton Street Social Club (Bottom Club), The Red Lodge, The Conservative Club, Saltburn Golf Club, Saltburn Cricket, Tennis and Bowls Club and The Queens (known locally as The Swingdoors).

Saltburn's first public house (independent of an existing hotel) was The Victoria, opened on 8 December 1982.

Today the following public houses exist in Saltburn: Alexandra Vaults (known locally as Back Alex), The Victoria, The Marine, The Ship Inn, Vista Mar and The Hop and Vine (formerly Windsor's).

Teddy's Nook is a house built in 1862 by Henry Pease, a director of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, for his own occupation. Pease was responsible for the foundation of the seaside resort and the sturdy sandstone house was first named The Cottage.

Lillie Langtry—The Jersey Lily, stayed at the house at sometime between 1877 and 1880. She was often visited by Edward Prince of Wales (later Edward VII of the United Kingdom) who had a suite of rooms at the Zetland Hotel. The cottage, consequently, became known as Teddy's Nook.

The Cottage was only one of four similar houses to be called Clifton Villas. The cottage was the family home of Audrey Collins, MBE, who served as Mayor of Saltburn and chair of the South Tees Health Authority. Middlesbrough's James Cook University Hospital has named a teaching unit in her name.

Locally knows as Fairy Glen, the Saltburn Valley Woods run through Saltburn Beck. Places in these woods include the Stepping Stones and the Saltburn Viaduct.

Saltburn's only secondary school is Huntcliff School which was rebuilt during 2007–8, re-opening on 8 September 2008. The redundant 50-year-old school buildings were then demolished to allow the town's Junior and Infant schools to relocate to the same site in 2009 because the Junior and Infant schools used to be located in a different building, not in the campus area.

In the early 1900's the building where the Earthbeat Centre is now located was previously a girls Grammar School, and a later a primary school until 2009. "After many months of intensive renovation the former Saltburn School has now opened its doors to the public as the Earthbeat Centre."The site is now the permanent home of The Earthbeat Centre for the next 50 years (as of 2015).

Tom Taylor (19 October 1817 – 12 July 1880) was an English dramatist, critic, biographer, public servant, and editor of Punch magazine. Taylor had a brief academic career, holding the professorship of English literature and language at University College, London in the 1840s, after which he practised law and became a civil servant. At the same time he became a journalist, most prominently as a contributor to, and eventually editor of Punch.

In addition to these vocations, Taylor began a theatre career and became best known as a playwright, with up to 100 plays staged during his career. Many were adaptations of French plays, but these and his original works cover a range from farce to melodrama. Most fell into neglect after Taylor's death, but Our American Cousin (1858), which achieved great success in the 19th century, remains famous as the piece that was being performed in the presence of Abraham Lincoln when he was assassinated in 1865.

Early years

Taylor was born into a newly wealthy family at Bishopwearmouth, a suburb of Sunderland, in north-east England. He was the second son of Thomas Taylor (1769–1843) and his wife, Maria Josephina, née Arnold (1784–1858). His father had begun as a labourer on a small farm in Cumberland and had risen to become co-owner of a flourishing brewery in Durham. After attending the Grange School in Sunderland, and studying for two sessions at the University of Glasgow, Taylor became a student of Trinity College, Cambridge in 1837, was elected to a scholarship in 1838, and graduated with a BA in both classics and mathematics. He was elected a fellow of the college in 1842 and received his MA degree the following year.

Taylor left Cambridge in late 1844 and moved to London, where for the next two years he pursued three careers simultaneously. He was professor of English language and literature at University College, London, while at the same time studying to become a barrister, and beginning his life's work as a writer. Taylor was called to the bar of the Middle Temple in November 1846. He resigned his university post, and practised on the northern legal circuit until he was appointed assistant secretary of the Board of Health in 1850. On the reconstruction of the board in 1854 he was made secretary, and on its abolition in 1858 his services were transferred to a department of the Home Office, retiring on a pension in 1876.

Writer

Taylor owed his fame and most of his income not to his academic, legal or government work, but to his writing. Soon after moving to London, he obtained remunerative work as a leader writer for the Morning Chronicle and the Daily News. He was also art critic for The Times and The Graphic for many years. He edited the Autobiography of B. R. Haydon (1853), the Autobiography and Correspondence of C. R. Leslie, R.A. (1860) and Pen Sketches from a Vanished Hand, selected from papers of Mortimer Collins, and wrote Life and Times of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1865). With his first contribution to Punch, on 19 October 1844, Taylor began a thirty-six year association with the magazine, which ended only with his death. During the 1840s he wrote on average three columns a month; in the 1850s and 1860s this output doubled. His biographer Craig Howes writes that Taylor's articles were generally humorous commentary or comic verses on politics, civic news, and the manners of the day. In 1874 he succeeded Charles William Shirley Brooks as editor.

Taylor also established himself as a playwright and eventually produced about 100 plays. Between 1844 and 1846, the Lyceum Theatre staged at least seven of his plays, including extravanzas written with Albert Smith or Charles Kenney, and his first major success, the 1846 farce To Parents and Guardians. The Morning Post said of that piece, "The writing is admirable throughout – neat, natural and epigrammatic". It was as a dramatist that Taylor made the most impression – his biographer in the Dictionary of National Biography (DNB) wrote that in writing plays Taylor found his true vocation. In thirty-five years he wrote more than seventy plays for the principal London theatres.

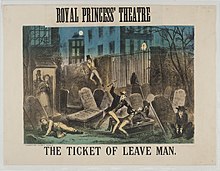

A substantial portion of Taylor's prolific output consisted of adaptations from the French or collaborations with other playwrights, notably Charles Reade. Some of his plots were adapted from the novels of Charles Dickens or others. Many of Taylor's plays were extremely popular, such as Masks and Faces, an extravaganza written in collaboration with Reade, produced at the Haymarket Theatre in November 1852. It was followed by the almost equally successful To Oblige Benson (Olympic Theatre, 1854), an adaptation from a French vaudeville. Others mentioned by the DNB are Plot and Passion (1853), Still Waters Run Deep (1855) and The Ticket-of-Leave Man (based on Le Retour de Melun by Édouard Brisebarre and Eugène Nus), a melodrama produced at the Olympic in 1863.Taylor also wrote a series of historical dramas (many in blank verse), including The Fool’s Revenge (1869), an adaption of Victor Hugo's Le roi s'amuse (also adapted by Verdi as Rigoletto), 'Twixt Axe and Crown (1870), Jeanne d'arc (1871), Lady Clancarty (1874) and Anne Boleyn (1875). The last of these, produced at the Haymarket in 1875, was Taylor's penultimate piece and only complete failure. In 1871 Taylor supplied the words to Arthur Sullivan's dramatic cantata, On Shore and Sea.

Like his colleague W. S. Gilbert, Taylor believed that plays should be readable as well as actable; he followed Gilbert in having copies of his plays printed for public sale. Both authors did so at some risk, because it made matters easy for American pirates of their works in the days before international copyright protection. Taylor wrote, "I have no wish to screen myself from literary criticism behind the plea that my plays were meant to be acted. It seems to me that every drama submitted to the judgment of audiences should be prepared to encounter that of readers".

Many of Taylor's plays were extremely popular, and several survived into the 20th century, although most are largely forgotten today. His Our American Cousin (1858) is now remembered chiefly as the play Abraham Lincoln was attending when he was assassinated, but it was revived many times during the 19th century with great success. It became celebrated as a vehicle for the popular comic actor Edward Sothern, and after his death, his sons, Lytton and E. H. Sothern, took over the part in revivals.

Howes records that Taylor was described as "of middle height, bearded [with] a pugilistic jaw and eyes which glittered like steel". Known for his remarkable energy, he was a keen swimmer and rower, who rose daily at five or six and wrote for three hours before taking an hour's brisk walk from his house in Wandsworth to his Whitehall office.

Some, like Ellen Terry, praised Taylor's kindness and generosity; others, including F. C. Burnand, found him obstinate and unforgiving. Terry wrote of Taylor in her memoirs:

Most people know that Tom Taylor was one of the leading playwrights of the 'sixties as well as the dramatic critic of The Times, editor of Punch, and a distinguished Civil Servant, but to us he was more than this. He was an institution! I simply cannot remember when I did not know him. It is the Tom Taylors of the world who give children on the stage their splendid education. We never had any education in the strict sense of the word yet through the Taylors and others, we were educated.

Terry's frequent stage partner, Henry Irving said that Taylor was an exception to the general rule that it was helpful, even though not essential, for a dramatist to be an actor to understand the techniques of stagecraft: "There is no dramatic author who more thoroughly understands his business".

In 1855 Taylor married the composer, musician and artist Laura Wilson Barker (1819–1905). She contributed music to at least one of his plays, an overture and entr'acte to Joan of Arc (1871), and harmonisations to his translation Ballads and Songs of Brittany (1865). There were two children: the artist John Wycliffe Taylor (1859–1925) and Laura Lucy Arnold Taylor (1863–1940). Taylor and his family lived at 84 Lavender Sweep, Battersea, where they held Sunday musical soirees. Celebrities who attended included Lewis Carroll, Charles Dickens, Henry Irving, Charles Reade, Alfred Tennyson, Ellen Terry and William Makepeace Thackeray.

Taylor died suddenly at his home in 1880 at the age of 62 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery. After his death, his widow retired to Coleshill, Buckinghamshire, where she died on 22 May 1905.