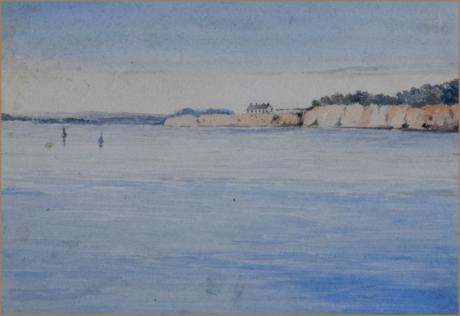

inscribed and datd in the margin " Cliffs at Pegwell Bay 1872/ from the Dover Steamer"

Pegwell Bay is a shallow inlet in the English Channel coast astride the estuary of the River Stour north of Sandwich Bay, between Ramsgate and Sandwich in Kent. Part of the bay is a nature reserve, with seashore habitats including mudflats and salt marsh with migrating waders and wildfowl. The public can access the nature reserve via Pegwell Bay Country Park, which is off the A256 Ramsgate to Dover road.

Archaeologists suggest that Pegwell Bay was the site of both Roman invasions of Britain by Julius Caesar. In 2017 the University of Leicester excavated a large fort dating from 54 BC; it was the previous lack of such evidence that had prevented historians from fixing the exact site of Caesar's landing. Pegwell Bay as it was in 1858 is recorded in a much-reproduced landscape painting by William Dyce, now in the Tate Gallery: Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th 1858. A pleasure pier was built in the 19th century in an effort to establish a seaside resort to rival nearby Ramsgate. This was not a success however, and was dismantled before the end of the century.

A full-size replica Scandinavian longboat complete with shields is situated by the main road on the low clifftops above Pegwell Bay to commemorate the first Anglo-Saxon landings in England hereabouts. The replica, named Hugin, sailed from Denmark to Thanet in 1949 to celebrate the 1,500th anniversary of the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain, the traditional landing of Hengist and Horsa, and the betrothal of Hengist's daughter, Rowena, to King Vortigern of Kent. Out of 53 crewmen only the navigator, Peter Jensen, was a professional seaman. Historic conditions were faithfully observed but with the addition of a sextant. The Hugin was offered as a gift to Ramsgate and Broadstairs by the Daily Mail in order for it to be preserved for centuries. The ship underwent extensive restoration in 2004–5.

Nearby Ebbsfleet is the site of the landing of the first Christian mission to southern England, by St Augustine, in 597 AD, commemorated by St Augustine's Cross. The Bay has treacherous bogs at low tide amongst the otherwise firm sands. These are used as plot points in Dennis Wheatley's 1938 thriller, Contraband. The attached map of Kent in the book shows two of the heroes in difficulties at Pegwell Bay.At the north east corner of the bay are the remains of Hoverlloyd's cross-channel hoverport. Vehicle and passenger carrying hovercraft operated from here from 1969 until 1982.

The London, Chatham and Dover Railway Company, in bringing their Hne to Dover, reckoned on making the cross-Channel passenger service a source of profit to their undertaking. They secured the Dover and Calais Mail contract in 1863, and, with it, the passenger traffic, which at once put the newly-formed railway in keen competition with the South Eastern Railway Company. The S.E. Company had their own harbour and steam packets at Folkestone, where they had already secured a well-established cross-Channel traffic, for although the sea route to Boulogne was longer, the journey beyond to Paris was shorter. Two years later the two Companies entered into a Continental agreement, by which all the railway receipts, attributable to the Channel Passage, along all parts of their systems between Margate and Hastings, were pooled, and divided in agreed proportions between the two Companies, depriving Continental travellers of any benefit that might have arisen from competition.

In the year 1863, when the Railway Company took over the Passage, the number of passengers was 123,053. It will be interesting, later, to compare that annual total with the increased number after the flight of nearly half a century ; but it will be more significant to notice the decrease of the annual total to 108,103, in 1870, five years after the Continental agreement had been brought into force. If natural causes had operated, there would have been the same steady increase in the Dover and Calais passengers as in preceding years; but the fact was the ill-matched pair of Railway Chairmen, before the ink of their agreement was dry, began to devise means of evading it by securing, on each side, the large.st share of Continental traffic for their own lines. Naturally, the South Eastern Company would do their best for their own harbour at Folkestone, in spite of the fact that the London and Chatham would take a share of the pool ; but the London and Chatham, having no proprietary interest in Dover Harbour, diverted a part of their Continental traffic at a point of their line beyond the limits of the Continental agreement, by a branch line from Sittingbourne to Queenborough, and thence by a line of steam packets to Flushing. This project was followed by two counter-moves by the South Eastern Company — one to open a new route via Port Victoria, near Queenborough ; and the other to build a large and attractive station just beyond the limits of Folkestone at Shorncliffe. These devices to get outside the Continental agreement were productive of little profit to the Railway Companies, and led to expensive litigation. The Flushing route proved to be only a " side show," the London and Chatham Company soon coming to the conclusion that the Dover route was their main stay. Railway rivalries and diversions in the " Seventies " had kept down the annual total of the Dover and Calais passengers to 197, 916, but as soon as the London, Chatham and Dover Railway Company made up their minds to make the most of Dover, the passengers increased, the annual total in 1888 being 235,695 ; and by the end of the " Eighties " the annual total touched 300,000; the year 1889 seeing an increase of nearly 1,000 passengers a week.