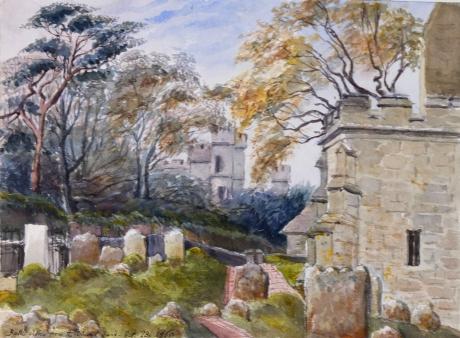

inscribed and dated "Battle Abbey from the Churchyard Oct 23 1860" and signed with initials "TT"

his article is about the abbey in England. For the historic structure in Richmond, Virginia, known as "Battle Abbey", see Virginia Historical Society.

Battle Abbey – Gate House |

|

|

Battle Abbey is a partially ruined Benedictine abbey in Battle, East Sussex, England. The abbey was built on the site of the Battle of Hastings and dedicated to St Martin of Tours. It is a Scheduled Monument.

The Grade I listed site is now operated by English Heritage as 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield, which includes the abbey buildings and ruins, a visitor centre with a film and exhibition about the battle, audio tours of the battlefield site, and the monks' gatehouse with recovered artefacts. The visitor centre includes a children's discovery room and a café, and there is an outdoor-themed playground.

The triple light window depicting the life of St John and the crucifixion of Jesus is claimed to have once adorned Battle Abbey which dates from 1045, removed during the Cromwell era to protect it from destruction. The legend goes that it was hidden for many years until it was transported to Tasmania to be fitted to the eastern end of the Buckland Church.

William the Conqueror had vowed to build a monastery in the event that he won the battle. In 1070, Pope Alexander II ordered the Normans to do penance for killing so many people during their conquest of England. William the Conqueror vowed to build an abbey where the Battle of Hastings had taken place, with the high altar of the church on the supposed spot where King Harold fell in battle on Saturday, 14 October 1066.

William started building it but died before it was completed. The Vill survey of 1076 and early legal documents of adjoining property refer to a hospital or guesthouse which was attached to the gate of the abbey. The monastic buildings were about a mile in circuit and formed a large quadrangle, the high altar of the church being on the spot where Harold fell. The church was finished in about 1094 and consecrated during the reign of his son William II (commonly known as William Rufus). The king presented there his father's sword and coronation robes.

The first monks were from the Benedictine Abbey of Marmoutier; the new foundation was dedicated to the Holy Trinity, St. Mary, and St. Martin. It was designed for one hundred and forty monks, though there were never more than sixty in residence at one time.

William I had ruled that the church of St Martin of Battle was to be exempted from all episcopal jurisdiction, putting it on the level of Canterbury. The abbey was enriched by many privileges, including the right of sanctuary, of treasure trove, of free warren, and of inquest, and the inmates and tenants were exempt from all episcopal and secular jurisdiction. It was ruled by a mitred abbot who afterward had a seat in Parliament and who had the curious privilege of pardoning any criminal he might meet being led to execution.

Walter de Luci became abbot in 1139 and made several improvements. During the reign of Henry II of England, rival church authorities at Canterbury and Chichester unsuccessfully tested the charter. At the Abbey was kept the famous "Roll of Battle Abbey" which was a list of all those who accompanied William from Normandy. As time went on and the honour of descent from one of these Norman families was more highly thought of, unauthentic additions seem to have been made.

The church was remodelled in the late 13th century, but virtually destroyed during the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1538 under King Henry VIII. At the time of the suppression of the Abbey (May 1538), there were seventeen monks in residence. The displaced monks of Battle Abbey were provided with pensions, including the abbot John Hamond and the prior Richard Salesherst, as well as monks John Henfelde, William Ambrose, Henry Sinden, Thomas Bede and Thomas Levett, all bachelors in theology.

The abbey and much of its land was given by Henry VIII to his friend and Master of the Horse, Sir Anthony Browne, who demolished the church and parts of the cloister and turned the abbot's quarters into a country house.

The abbey was sold in 1721 by Browne's descendant, Anthony Browne, 6th Earl of Montagu, to Sir Thomas Webster, MP and baronet. Webster was succeeded by his son, Sir Whistler Webster, 2nd Baronet, who died childless in 1779, being succeeded in the baronetcy by his brother. Battle Abbey remained in the Webster family until 1857, when it was sold to Lord Harry Vane, later Duke of Cleveland. On the death of the Duchess of Cleveland in 1901, the estate was bought back by Sir Augustus Webster, 7th baronet.

Sir Augustus (son of Sir Augustus, 7th baronet) was born in 1864 and succeeded his father as 8th baronet in 1886. Sir Augustus was formerly a captain in the Coldstream Guards. With the death of the 8th baronet in 1923, the baronetage became extinct. The Abbot's house was an all-girls boarding school; Canadian troops were stationed there during the Second World War.

In 1976, Augustus Webster's heirs sold Battle Abbey to the British government, and it is now in the care of English Heritage. In 2016, Historic England commissioned tree-ring analysis of oak timbers from the gatehouse, dorter and reredorter to help identify when these areas might have been built. Findings imply phased building and local timber acquisition, with samples indicating early and later fifteenth century building work.

The church's high altar reportedly stood on the spot where Harold died. This is now marked by a plaque on the ground, and nearby is a monument to Harold erected by the people of Normandy in 1903. The ruins of the abbey, with the adjacent battlefield, are a popular tourist attraction, with events such as the Battle of Hastings reenactments.

All that is left of the abbey church itself today is its outline on the ground, but parts of some of the abbey's buildings are still standing: those built between the 13th and 16th century. These are still in use as the independent Battle Abbey School. Visitors to the abbey are usually not allowed inside the school buildings, although during the school's summer holidays, access to the abbot's hall is often allowed.

-

Battle Abbey

-

Monument to Harold

-

Battle Abbey – Novices Common Room

-

Novices' Chamber

-

Battle Abbey – Dorter, remains of cloister and Battle Abbey School

-

Battle Abbey re-enactment -

Tom Taylor (19 October 1817 – 12 July 1880) was an English dramatist, critic, biographer, public servant, and editor of Punch magazine. Taylor had a brief academic career, holding the professorship of English literature and language at University College, London in the 1840s, after which he practised law and became a civil servant. At the same time he became a journalist, most prominently as a contributor to, and eventually editor of Punch.

In addition to these vocations, Taylor began a theatre career and became best known as a playwright, with up to 100 plays staged during his career. Many were adaptations of French plays, but these and his original works cover a range from farce to melodrama. Most fell into neglect after Taylor's death, but Our American Cousin (1858), which achieved great success in the 19th century, remains famous as the piece that was being performed in the presence of Abraham Lincoln when he was assassinated in 1865.

Early years

Taylor was born into a newly wealthy family at Bishopwearmouth, a suburb of Sunderland, in north-east England. He was the second son of Thomas Taylor (1769–1843) and his wife, Maria Josephina, née Arnold (1784–1858). His father had begun as a labourer on a small farm in Cumberland and had risen to become co-owner of a flourishing brewery in Durham. After attending the Grange School in Sunderland, and studying for two sessions at the University of Glasgow, Taylor became a student of Trinity College, Cambridge in 1837, was elected to a scholarship in 1838, and graduated with a BA in both classics and mathematics. He was elected a fellow of the college in 1842 and received his MA degree the following year.

Taylor left Cambridge in late 1844 and moved to London, where for the next two years he pursued three careers simultaneously. He was professor of English language and literature at University College, London, while at the same time studying to become a barrister, and beginning his life's work as a writer. Taylor was called to the bar of the Middle Temple in November 1846. He resigned his university post, and practised on the northern legal circuit until he was appointed assistant secretary of the Board of Health in 1850. On the reconstruction of the board in 1854 he was made secretary, and on its abolition in 1858 his services were transferred to a department of the Home Office, retiring on a pension in 1876.

Writer

Taylor owed his fame and most of his income not to his academic, legal or government work, but to his writing. Soon after moving to London, he obtained remunerative work as a leader writer for the Morning Chronicle and the Daily News. He was also art critic for The Times and The Graphic for many years. He edited the Autobiography of B. R. Haydon (1853), the Autobiography and Correspondence of C. R. Leslie, R.A. (1860) and Pen Sketches from a Vanished Hand, selected from papers of Mortimer Collins, and wrote Life and Times of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1865). With his first contribution to Punch, on 19 October 1844, Taylor began a thirty-six year association with the magazine, which ended only with his death. During the 1840s he wrote on average three columns a month; in the 1850s and 1860s this output doubled. His biographer Craig Howes writes that Taylor's articles were generally humorous commentary or comic verses on politics, civic news, and the manners of the day. In 1874 he succeeded Charles William Shirley Brooks as editor.

Taylor also established himself as a playwright and eventually produced about 100 plays. Between 1844 and 1846, the Lyceum Theatre staged at least seven of his plays, including extravanzas written with Albert Smith or Charles Kenney, and his first major success, the 1846 farce To Parents and Guardians. The Morning Post said of that piece, "The writing is admirable throughout – neat, natural and epigrammatic". It was as a dramatist that Taylor made the most impression – his biographer in the Dictionary of National Biography (DNB) wrote that in writing plays Taylor found his true vocation. In thirty-five years he wrote more than seventy plays for the principal London theatres.

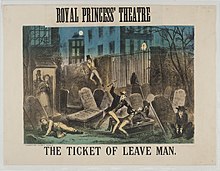

A substantial portion of Taylor's prolific output consisted of adaptations from the French or collaborations with other playwrights, notably Charles Reade. Some of his plots were adapted from the novels of Charles Dickens or others. Many of Taylor's plays were extremely popular, such as Masks and Faces, an extravaganza written in collaboration with Reade, produced at the Haymarket Theatre in November 1852. It was followed by the almost equally successful To Oblige Benson (Olympic Theatre, 1854), an adaptation from a French vaudeville. Others mentioned by the DNB are Plot and Passion (1853), Still Waters Run Deep (1855) and The Ticket-of-Leave Man (based on Le Retour de Melun by Édouard Brisebarre and Eugène Nus), a melodrama produced at the Olympic in 1863.Taylor also wrote a series of historical dramas (many in blank verse), including The Fool’s Revenge (1869), an adaption of Victor Hugo's Le roi s'amuse (also adapted by Verdi as Rigoletto), 'Twixt Axe and Crown (1870), Jeanne d'arc (1871), Lady Clancarty (1874) and Anne Boleyn (1875). The last of these, produced at the Haymarket in 1875, was Taylor's penultimate piece and only complete failure. In 1871 Taylor supplied the words to Arthur Sullivan's dramatic cantata, On Shore and Sea.

Like his colleague W. S. Gilbert, Taylor believed that plays should be readable as well as actable; he followed Gilbert in having copies of his plays printed for public sale. Both authors did so at some risk, because it made matters easy for American pirates of their works in the days before international copyright protection. Taylor wrote, "I have no wish to screen myself from literary criticism behind the plea that my plays were meant to be acted. It seems to me that every drama submitted to the judgment of audiences should be prepared to encounter that of readers".

Many of Taylor's plays were extremely popular, and several survived into the 20th century, although most are largely forgotten today. His Our American Cousin (1858) is now remembered chiefly as the play Abraham Lincoln was attending when he was assassinated, but it was revived many times during the 19th century with great success. It became celebrated as a vehicle for the popular comic actor Edward Sothern, and after his death, his sons, Lytton and E. H. Sothern, took over the part in revivals.

Howes records that Taylor was described as "of middle height, bearded [with] a pugilistic jaw and eyes which glittered like steel". Known for his remarkable energy, he was a keen swimmer and rower, who rose daily at five or six and wrote for three hours before taking an hour's brisk walk from his house in Wandsworth to his Whitehall office.

Some, like Ellen Terry, praised Taylor's kindness and generosity; others, including F. C. Burnand, found him obstinate and unforgiving. Terry wrote of Taylor in her memoirs:

Most people know that Tom Taylor was one of the leading playwrights of the 'sixties as well as the dramatic critic of The Times, editor of Punch, and a distinguished Civil Servant, but to us he was more than this. He was an institution! I simply cannot remember when I did not know him. It is the Tom Taylors of the world who give children on the stage their splendid education. We never had any education in the strict sense of the word yet through the Taylors and others, we were educated.

Terry's frequent stage partner, Henry Irving said that Taylor was an exception to the general rule that it was helpful, even though not essential, for a dramatist to be an actor to understand the techniques of stagecraft: "There is no dramatic author who more thoroughly understands his business".

In 1855 Taylor married the composer, musician and artist Laura Wilson Barker (1819–1905). She contributed music to at least one of his plays, an overture and entr'acte to Joan of Arc (1871), and harmonisations to his translation Ballads and Songs of Brittany (1865). There were two children: the artist John Wycliffe Taylor (1859–1925) and Laura Lucy Arnold Taylor (1863–1940). Taylor and his family lived at 84 Lavender Sweep, Battersea, where they held Sunday musical soirees. Celebrities who attended included Lewis Carroll, Charles Dickens, Henry Irving, Charles Reade, Alfred Tennyson, Ellen Terry and William Makepeace Thackeray.

Taylor died suddenly at his home in 1880 at the age of 62 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery. After his death, his widow retired to Coleshill, Buckinghamshire, where she died on 22 May 1905.