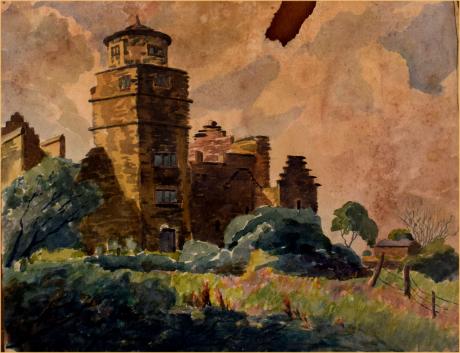

inscribed on the reverse " Arden Hall / Reddich Vale "

The most famous of the halls of Bredbury, Arden Hall, erected in 1597, is now a ruin standing in a commanding position above the valley of the River Tame. For over two centuries it was owned by the Ardernes, who had other possessions in Cheshire and were a junior branch of the Arden family of Warwickshire, of whom William Shakespeare's mother was a member.

The building was at one time "a tall building, narrow in proportion to its height and length, built of flat stones or parpoints, and having a sturdy watchtower at the back, looking over the valley of the River Tame. It was surrounded by a wide and deep moat. On the front were three gables, two of them projecting from the face of the hall, the third being flush with it. The entrance doorway was in the side of the central gable, and was approached from the courtyard by a flight of steps. Passing through the doorway a heavy oak door on the right side opened at once into the Great Hall, and in the tower exactly opposite was a wide oak staircase, which led to the upper part of the house. The Great Hall occupied the whole of the ground floor of this portion of the building, and was about 33 feet (10 m) long by 24 feet (7.3 m) wide. At the end was a raised platform where the high table was situated, lighted by two loft bay windows, one at each end. The year in which some portion of the hall, if indeed not the whole of it, was erected, is fixed from the date 1597 on the spout above the entrance, and the initials and date R A 1597 on the right hand gable."

In the particulars of sale of 1825, it states that "the ancient mansion house of Arden Hall has been in part converted into a commodious farm house, with every requisite convenience", and it had already been let as such. There is a tradition that Oliver Cromwell stayed at the hall and that there was a skirmish nearby between Cavaliers and Roundheads, but there is no firm evidence, although the access to the hall is called Battle Lane. However, Ralph Arderne, like most other local gentry, espoused the Parliamentarian cause, and saw action in several engagements.

The town reaches to the lower southern slopes of Werneth Low, an outlier of the Peak District between the valleys of the River Tame and River Goyt, head-waters of the River Mersey.

The area must have been unattractive to the Brigantes settlers in pre-Roman Britain, with its bleak hilltop, the heavy clay soil of the intermediate land probably covered by trees and becoming marshy where the slopes flattened out, and the swampy valley floors. The rivers flowed more fully before their waters were dammed in the 19th century to supply Manchester, Stockport and other towns. However, where the valley of the River Goyt narrows at New Bridge, passage was possible, and here an ancient highway entered the village to proceed along the higher land to the north-east.

The Romans surveyed and constructed a road between the forts of Mamucium (Manchester) and Ardotalia (Melandra Castle at Gamesley) over this ancient track and this in turn became an 18th-century turnpike road and the Liverpool to Skegness trunk road, the A560.

Some years ago[when?] a Roman coin was dug up on the edge of the road between Bredbury railway station and St Mark's Church. The coin long antedates any Roman occupation of this part of the country, and may either have been lost when held as a souvenir or have been brought over from the continent in the course of trade.

As with the majority of hills, rivers and other natural features in this area, the names of the River Tame and Werneth Low are of Celtic origin. The name Bredbury is Anglo-Saxon and probably dates from the first permanent settlement. Names found in nearby villages suggest that Norse invaders found their way into the district, probably during the 10th century.

Bredbury comprised farm land bought by Lord Danton in 1014. There is no mention of Lord Danton's manor, but the 'lord' of Bredbury was the pre-conquest Anglo-Saxon thane, Wulfric. It is likely that William the Conqueror's army, on its march from Yorkshire to subdue the rebellion at Chester, followed the main highway. Virtually all the townships on the way were systematically looted, part of the Harrying of the North. Bredbury seems to have been an exception, for reasons which are unclear, but the army apparently crossed the hill into Romiley, which although not on the direct route, is duly described as "waste" in the Domesday Book of 1086. Bredbury itself was mentioned briefly in the Domesday Book as being several hundred acres of land. The only occupants listed were a duck and a sheep. Its value was placed at three pounds.

Bredbury passed from the hands of Sir Richard de Vernon to the Mascis of Dunham, under whom it was held by the Fitz-Waltheofs of Stockport. A charter granted by the third Hamon de Masci, lord of Dunham, who died about the end of the reign of King John, confirms the ownership of lands in Bredbury to the Fitz-Waltheofs, and is of special interest because it affords an insight into the working of the feudal system of the period. A translation of the charter runs as follows:

And I, Hamo, regrant to Robert, the son of Waltheof, Bredbury and Brinnington, with their appurtenances, as his inheritance, to him and his heirs, to hold of me and my heirs, by the service of carrying my bed, my arms or my clothing, whenever the Earl of Chester in his own proper person shall go to Wales. And I, Hamo, will fully furnish Robert, the sone of Waltheof, and his heirs, with a sumpter beast and a man and a sack, and we will find estovers (sufficient food) whilst he is with us in the field, until he shall be returned, to the said Robert or his heirs. And Robert, the son of Waltheof, shall pay to ransom my body from captivity and detention, and to make my eldest son a knight, and to give my eldest daughter a marriage portion, in consideration of which Robert has given me a gold ring.

The conditions laid down in this charter were usual under the feudal system, when military expeditions into Wales were no uncommon tasks for the Earl of Chester and his underlords.

By a general inquisition of tenures, taken 10 May 1288, to determine the services due to Edward I in the Welsh Wars, it was found that "Richard de Stokeport holds Bredbury of Hamo de Masci" and "makes service to our Lord the King with one uncaparisoned horse".

Some time during the 14th century the manor of Bredbury was sub-divided into two portions, the larger of which was held by the Bredburys, and passed from them, by marriage with an heiress, to the Ardernes. The remaining portion ultimately came into the possession of the Davenports of Henbury.

It would appear, however, that the manor of Bredbury was still held by the Stokeports, for in the inquisition post mortem of Isabel, daughter and heiress of Sir Richard de Stokeport, taken in 1370, it was found that the manor of Bredbury, with its appurtenances, was held from Roger Lestrange, lord of Dunham Massey, by knight's service, and that it was worth 100 shillings per annum.

In the same year, another inquisition was taken on the death of Hugh de Davenport, which records that he died "seised of two parts of the manor of Bredbury, and of land in Romiley and Werneth" and that Thomas de Davenport was his son and heir, aged 12 years. These lands remained in the possession of the Davenports for several generations The manor house of the Davenports in Bredbury was Goyt Hall on the banks of the River Goyt.

During the Middle Ages the wealth of the Kingdom of England arose largely from the export of wool to the Netherlands, but the district had no share in this prosperity. By Tudor times, however, conditions had changed. Continental trade had been ruined by the Dutch War of Independence and home production of cloth was encouraged. By this time too, the wolves of Longdendale had been exterminated. Great flocks of sheep grazed on the moors and hillsides of the district, sheep farmers and weavers prospered, and established families such as the Ardernes and, at nearby Marple, the Bradshaws became wealthy and influential. The local industries based on thesheep farming, in the absence of ready water power, remained domestic – mainly handloom weaving and the making of felt hats.