Baring, Sir Francis, first baronet (1740–1810), merchant and merchant banker, was born at Larkbear, Exeter, on 18 April 1740, third of the four surviving sons and one daughter of John Baring (1697–1748) and his wife, Elizabeth Baring (1702–1766), daughter of John Vowler, a prosperous Exeter ‘grocer’ who dealt largely in sugar, spices, teas, and coffee. Despite being partially deaf from an early age, in 1762 Francis Baring established the London merchant house of Barings. He emerged as a powerful merchant banker and by the mid-1790s reckoned that his concerns had been ‘more extensive and upon a larger scale than any merchant in this or any other country’ (Barings archives, Northbrook MSS, A7).

Early life

Baring's father, the son of a Lutheran pastor, emigrated from Bremen in 1717 and settled at Exeter, where he became a leading textile merchant and manufacturer, and a landowner; other than the bishop and the recorder, apparently he alone in Exeter kept a carriage. His premature death in 1748 resulted in Francis, aged eight, being brought up and strongly influenced by his mother. Her sound business head doubled her firm's worth and in 1762 she extended the business to London.

In preparation for this, in the early 1750s Francis was dispatched to London for education at Mr Fargue's French school at Hoxton and then at Mr Fuller's academy in Lothbury. Samuel Touchet, merchant of London, accepted him in 1755 for a seven-year apprenticeship, charging his mother a substantial premium of £800. Immediately upon his release, on Christmas day 1762 he joined his two surviving brothers in the interlocking partnerships of John and Francis Baring & Co. of London and John and Charles Baring & Co. of Exeter. Francis led the London concern and Charles the Exeter one, while John, a leading Exeter citizen and an MP from 1776, was a sleeping partner and the nominal head of both firms.

Initially the London business comprised the accounts and goodwill transferred to it from an old family friend, Nathaniel Paice, a London merchant who was retiring, but also much business came from John and Charles Baring & Co. and other Exeter merchants who required a London agent. Agency services for overseas merchants and trading speculations were soon added. But the firm lost money in eight of its first fourteen years, as Francis Baring learnt how to judge markets; having started out with £10,000 he reckoned that by 1777 his net worth stood at just £2500.

Notwithstanding these private reverses, the City of London quickly recognized Baring's special qualities and in 1771 the Royal Exchange Assurance, a giant public business, appointed him to its court. He underpinned his directorship, which continued until 1780, with a holding of £820 in the company's stock, no mean sum when his assets totalled £13,000. This appointment was important to hold; for the first time he was marked out from the throng of merchants populating the courts and alleys of the City.

On 12 May 1767, at Croydon, Baring married Harriet Herring (1750–1804). Over the years she contributed about £20,000 to the family coffers, received from her merchant father, William Herring of Croydon, and a cousin, Thomas, archbishop of Canterbury. Otherwise her early contributions were her frugality in managing a household accommodated above the business and, between 1768 and 1787, a capacity to bear six sons and six daughters, among them Harriet Wall, religious controversialist. Later she emerged as a glittering social hostess, ‘devoted to fashionable society’ (Barings archives, DEP249), but this took its toll. Her health was ‘irretrievably impaired by late hours and over-excitement’ (ibid.), and she died comparatively young in 1804. In contrast her husband preferred ‘the more tranquil enjoyment of a domestic circle’ (Public Characters, 1805, 38). Harriet also introduced her husband to valuable business contacts. Harriet's sister Mary in 1766 married one of London's leading private bankers, Richard Stone of Martin & Co., with whom Francis Baring's firm had opened an account in 1764.

Independence from Exeter

Baring's early business was constrained through the demands placed upon it by the much larger Exeter firm, which suffered under Charles Baring's speculations of a ‘wild, strange, incoherent description’ (Barings archives, Northbrook MSS, D1). The resulting conflict was only resolved in early 1777, when Baring took the initiative in dissolving the interlocking partnerships. Capital and management were now entirely separate, though Francis maintained strong family links with Exeter. Regularly he employed his wealth to rescue Charles from ruin and thus preserve the good name of his family; his motivation was an intense desire to see business and family prosper. Thus he was scandalized by Charles's ‘almost monstrous management of the original and chief dependence of the Baring family’ (ibid., D7).

Baring's brother John remained a sleeping partner until his retirement in late 1800. In 1781 two nominal partners were appointed, J. F. Mesturas, formerly a clerk, and Charles Wall, who in September 1790 married Baring's eldest daughter, Harriet. The two were soon afterwards promoted full partners. However, Mesturas withdrew in 1795 and was not replaced. Thus from 1777 until his retirement in 1804, Baring led the firm almost singlehandedly, for many years having Wall as his sole active partner.

The partnership capital grew steadily from £20,000 in 1777 to £70,000 in 1790, and to £400,000 in 1804. Baring came to contribute the major share, providing 12 per cent in 1777, 40 per cent in 1790, and 54 per cent in 1804. Annual profits rose to £40,000 in the 1790s and peaked, untypically, at over £200,000 in 1802; they were calculated after payment to partners at 4 per cent interest, sometimes 5 per cent, on their capital. Baring's share of the profits increased steadily from a quarter in the mid-1760s to a half from 1777 and to three-quarters from 1801. His total wealth, business as well as private, rose accordingly, from almost £5000 in 1763, to £64,000 in 1790, and to £500,000 in 1804.

Building a correspondent network

Early on Baring's business profits were derived mostly from international trade, especially between Britain, the western European coast, the Iberian peninsula, Italy, the West Indies, and, from the 1770s, North America. They arose from trading on sole account or, more often, on joint account with other merchants; from acting as London agent for overseas merchants, buying and selling consignments, making and collecting payments, and arranging shipping and warehousing; and, in due course, from trade finance through making advances or, more frequently, accepting bills of exchange.

The success of this work was greatly influenced by the establishment of a powerful network of corresponding houses in the main international trading centres. These alliances with leading European and North American merchants were the keys to his success. Their establishment serves to underline Baring's outstanding personal qualities which seemingly effortlessly won him the confidence of older merchants. ‘His great characteristics’, wrote one contemporary, ‘are method and dexterity in business, a sound judgement and a most excellent heart’ (Public Characters, 1805, 38–9).

Hope & Co. of Amsterdam, the most powerful merchant bank in Europe's leading financial centre, was Baring's most valuable connection. Their association is said to have begun in the 1760s, when Hopes passed Baring some bills to negotiate and ended up ‘exceedingly struck with the transaction which bespoke not only great zeal and activity, but what was still more important … either good credit or great resources … From that day Baring became one of their principal friends’ (Barings archives, DEP249). The link was consolidated in other ways, in particular through the marriage in 1796 of Pierre César Labouchère [see under Hope family], a leading figure at Hopes, to Baring's third daughter, Dorothy.

Vital connections were also established on the other side of the Atlantic. Baring was quicker than most to see the commercial potential of Britain's North American colonies, and his finance house quickly emerged as the European hub of a network of America's most powerful merchants. In 1774 his first American customer was the leading Philadelphia merchant trader, Willing, Morris & Co.; its influential partners included Robert Morris, a future financial architect of American independence from Britain, and Thomas Willing, a future president of the Bank of the United States. Through them Baring was introduced to Senator William Bingham, one of America's wealthiest men, a connection which gave rise to several lucrative transactions.

Government adviser

Baring's work from 1782 as an adviser on commercial matters to cabinet ministers propelled him from relative obscurity to the inner circles of British political life, underlining how in these early years his influence was entirely disproportionate to the resources he commanded. The catalyst for this advancement was his Devon connections. His brother John was elected to parliament as a member for Exeter in 1776; more importantly, in 1780 his sister, Elizabeth, married another MP and fellow Devonian, John Dunning.

A rich and influential lawyer, Dunning was allied to Lord Shelburne, a powerful whig politician who held progressive views on political economy and whose borough of Calne Dunning represented in parliament. In July 1782, following Shelburne's promotion to prime minister and Dunning's appointment as chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster, Baring fulfilled the new prime minister's need ‘to have recourse from time to time to mercantile advice’ (Barings archives, Northbrook MSS, B1). Baring, by instinct a whig, became Shelburne's confidential adviser on commerce, or his ‘handy City man’, according to a discontented William Cobbett. Baring's ideas on political economy and commerce were well ahead of his time; in 1799 he rightly defended the Bank of England's decision (in 1797) to suspend specie payments as both correct and inevitable, in the face of hostile opposition from many of his peers.

Baring's knowledge of North American merchants and trade made him especially useful in the closing years of the American War of Independence when Shelburne, anxious for a liberal settlement, invited his comments on commercial aspects of the proposed peace treaty with the United States. Shelburne introduced Baring to Isaac Barré, his paymaster-general, and to such leading luminaries as William Pitt the younger, Henry Dundas, Jeremy Bentham, Edmund Burke, Sir Samuel Romilly, and lords Erskine, Camden, Sydney, and Melville. However, Baring's friendship with Lord Lansdowne (as Shelburne became in 1784), Dunning, and Barré ran particularly deep, and in 1787 he drew public attention to it by commissioning their triple portrait from Sir Joshua Reynolds. A private financial connection also existed. For six years from 1783 Baring loaned Lansdowne £5000, on security of a debt owing to Lansdowne. In 1805, on Lansdowne's death, Baring became a trustee of his estate, charged with the task of liquidating debts of £90,000.

Baring was not nearly as close to the tory leader William Pitt, who followed Lansdowne as prime minister and who held office almost continuously until Baring's retirement from active business. Their views were far apart, and on Pitt's death Baring was quick to stress their lack of concurrence ‘on any great political question for above 20 years, our political opinions and principles being different’ (The Times, 6 Feb 1806). In particular he disagreed with Pitt's policy for the seemingly endless continuation of a wasteful war; they also suffered differences over government policy towards the East India Company. Baring's personal influence in government waned but his expert advice, always fairly delivered, continued to be provided on such matters as trade with Turkey, the importance of Gibraltar, and the funding of the national debt. As part of Pitt's cleansing of abuse from public office, in 1784 he appointed Baring a commissioner charged with investigating fees, gratuities, and prerequisites for holding certain offices.

The link with Lansdowne led Baring to the Commons in 1784 when, at a cost of £3000, he was elected MP for Grampound, Devon. He was ousted six years later, after which he stood unsuccessfully for Ilchester. Later he sat for Lansdowne's safe boroughs of Chipping Wycombe, Oxfordshire (1794–6 and 1802–6), and Calne, Wiltshire (1796–1802), which had formerly been represented by other Lansdowne favourites, Dunning and Barré. Notwithstanding his admission that ‘my voice is so very unequal to the House of Commons’ (Barings archives, Northbrook MSS, N4.4.295), his speeches were reckoned to be ‘neat, flowing and perspicuous, aiming more by solidity of argument to arrest and convince his hearers, than by beautiful figures and impassioned eloquence to mislead the minds of men’ (Daily Advertiser, Oracle and True Briton, 12 Oct 1805).

Both in private and from the benches, Baring advocated greater freedom of trade. ‘Every regulation’, he said, ‘is a restriction, and as such contrary to that freedom which I have held to be the first principle of the well being of commerce’, for good measure adding that

a restriction, or regulation, may doubtless answer the particular purpose for which it is imposed, but as commerce is not a simple thing, but a thing of a thousand relations, what may be of profit in the particular, may be ruinous in general. (Public Characters, 1805, 34)

Government business in the 1780s

There can be little doubt that Baring's firm benefited directly as well as indirectly from his political connections, in particular from Barré's almost limitless patronage as paymaster-general during the American War of Independence. In 1782 he advised Lansdowne that in 1781 and 1782 contractors' profits from supplying the army abroad represented over 13 per cent of the total value of transactions. Baring won the 1783 contract on the basis of 1 per cent commission, and, when war ended and the contract was terminated prematurely, he won contracts for the disposal of stores. Government savings were at least 10 per cent and Baring was personally rewarded in other ways. Between 1784 and 1786 he (and not his firm) received £7000 in commissions for undertaking government work and a further £4250 from interest on government money in his hands. Against this, in his private accounts he charged the £3000 expenses incurred in winning his Commons seat in 1784. Nevertheless, transactions for the government stretched his resources in these years. He apparently ‘borrowed’ stock from Martin & Co., his brother-in-law's firm, ‘to enable me to negotiate the government business’ (Barings archives, DEP193.40). Yet the returns on these risky adventures were clearly immense. During the war, when government expenditure soared, his firm also emerged as a contractor for marketing British government debt; it was believed to have made profits of £19,000.

The East India Company

Francis Baring's other distraction from his firm was his directorship of the East India Company from 1779. By 1783 he led the City interest on the company's court, and in 1786 he was reckoned its most able member. His commitment was significant; he gave up each Wednesday and occasionally a Friday to its affairs. Notwithstanding his views on the liberalization of American trade, he promoted the company's monopoly and commercial independence ‘with an ardour contrary to the usual moderation of his character’ (Public Characters, 1805). He joined the East India Company when the British government was anxious to exert greater political control over it, recognizing the great territorial power that it had become. Baring actively fought off the far-reaching proposals of Lord North and Charles James Fox, believing that ‘India is not a colony and God forbid that it ever should be’ (Barings archives, Northbrook MSS, N4.5), but he worked with an old friend from the period of his apprenticeship and now a fellow director, Richard Atkinson, to modify and facilitate the acceptance of Pitt's India Act. In 1792 and 1793, as Pitt's preferred candidate, he was elected chairman and charged with the task of renegotiating the company's charter.

The experience of his chairmanship was both exhausting and distracting. His private accounts went unwritten for two years and in 1792, ‘being obliged to travel for my health’ (Barings archives, DEP193.40), he was utterly unprepared for the collapse in prices of British government securities which reduced his private capital of £20,000 by half. ‘The more I work’, he confided to Lansdowne, ‘the greater the degree of jealousy and difficulty I have to encounter amongst the directors who are in general composed of either knaves or fools’ (ibid., DEP193.17.1). Pitt rewarded Baring with a baronetcy on 29 May 1793, and he soldiered on as a director until his death in 1810, but increasingly he was disillusioned and absent from the court. As early as 1798 he had lost ‘much of that consequence … which his superior knowledge, experience and abilities entitle him to’ (C. H. Philips, The East India Company, 1784–1834, 1940, 164).

Transactions with Hope & Co.

Throughout Baring's lifetime his good commercial intelligence, sound judgement, nimble-footedness, and instinct for speculative profit remained the hallmarks of his business style. Thousands of speculations detailed in his firm's ledgers attest to this, but his burgeoning business and rising confidence were graphically illustrated in 1787 when Hopes introduced him to speculation on a grand scale. The two houses set about controlling the entire European cochineal market by secretly buying up all available stocks, one quarter for Barings and the rest for Hopes. Correspondents from St Petersburg to Cadiz spent £450,000 but prices remained static and in 1788, with a huge loss anticipated, the partners of Barings agreed ‘to forgo any participation of the profits of the trade for the last year’ (Barings archives, DEP193.40).

The resumption of war in 1793 provided new challenges and opportunities. The evacuation of Hopes to London between 1795 and 1803, when Amsterdam was occupied by France, and the availability of their expertise, contacts, and capital to Barings were of immense assistance. The two houses embarked on bold transactions—invariably with a quarter for Barings and the rest for Hopes. Their first adventure was entirely private and aimed to secure a substantial part of their capital from the dangers of European revolutions and wars. In late 1795 Baring dispatched his 22-year-old son, Alexander, to Boston to negotiate and execute the purchase of more than 1 million acres of land in Maine for £107,000. The investment was introduced by the land's owner, Senator William Bingham, son-in-law of Barings' Philadelphia correspondent, Thomas Willing, and yet another friend of Lansdowne. Francis Baring undertook the initial appraisal and commitment to the investment, and the negotiations were left to his son Alexander, who afterwards remained in North America as Barings' representative and who consolidated his position by marrying Bingham's eldest daughter, Ann Louisa. The link was further strengthened through the marriage of Baring's third son, Henry, to Bingham's other daughter, Maria, in 1802. Both marriages brought considerable wealth to the Baring family.

Wartime finance

British government expenditure, which grew to unprecedented levels during the European wars, created great opportunities for London merchant bankers such as Sir Francis Baring. After 1799 his firm headed the list of public debt contractors in twelve of the next fifteen years, supposedly giving rise to total profits of £190,000. For Baring, a key financier of the nation's war effort, it represented the pinnacle of his power and standing. Despite his retirement in 1804, he continued to appear as a contractor until his death because, as he explained, ‘it was thought my name would be useful in the opinion of the publick’ (Barings archives, Northbrook MSS, A21).

Britain's European allies needed funds and came to Baring who, with Hopes, now organized some of the first marketings of foreign bonds in London. Believing fervently that ‘it may be desirable not to have the subject to discuss with our own Ministers, as you know very well how ignorant they are of foreign finance’ (Barings archives, Northbrook MSS, A19), in 1801 he dispatched P. C. Labouchere of Hopes and his son George to negotiate a loan to the court of Lisbon. The resulting ‘Portuguese diamond loan’ of 13 million guilders was shared between Barings and Hopes on the usual 25:75 basis.

Of equal strategic importance was Baring's transmission of British government subsidies to allied governments to support their war efforts. This highly secret and sensitive work required expert knowledge of money transmission and a sound correspondent network; again it underlined the government's confidence in Baring. Opportunities for direct financing of the enemy were also presented to Baring, who knew he could hoodwink the government into consenting to them; ‘but to have obtained that licence we must have presented a memorial so equivocal and in truth so unfounded that it would not suit us and therefore was abandoned’ (Barings archives, DEP3.3.3, Francis Baring to Alexander Baring, 20 May 1799).

Baring applied a looser criterion in his choice of trading partners, however. Links with leading American merchants, such as the Codmans of Boston, Willing and Francis of Philadelphia, Robert Gilmour, and Robert Oliver & Brothers of Baltimore were now immensely important to Barings' business as its axis swung from continental European to transatlantic trade. In sustaining these extensive connections Baring undoubtedly facilitated, albeit passively, the breaching of Britain's continental blockade.

American finance

Close connections with American merchants inevitably resulted in links with the United States government. Since the close of the American War of Independence, Baring had kept watch over the American government's finances in Europe. However, his first significant transaction for its account was the sale in 1795 of $800,000 worth of stock and the remittance of the proceeds in support of American negotiations with the north African Barbary powers. To secure the transaction Francis Baring admitted to acting with ‘zeal, perhaps imprudence, in going beyond the letters of my orders’ (New York Historical Society, Rufus King MSS, vol. 39, fol. 17), but the American ambassador in London commended his ‘liberal and skilfull manner’ and undertook to ensure that the government would ‘entertain a proper sense of your Service in this Business’ (ibid., vol. 51, fol. 461). Other business soon followed, including the sale of the government's shares in the Bank of the United States and the purchase of munitions from British manufactures for the government's account.

Considered to be an ‘English house of the first reputation and solidity’ (New York Historical Society, Rufus King MSS, vol. 55, fols. 378–9), Barings in 1803 was appointed London financial agent for the United States government, leaving Sir Francis Baring's influence in North American financial affairs unrivalled in London. At about this time, when a short interval of peace existed after the peace of Amiens, Baring led his house, alongside Hopes, into its largest and most prestigious transaction yet. The French government wanted to sell 1 million square miles of the Territory of Louisiana, and the United States administration wanted to buy it; the purchase price was $15 million and Francis Baring was charged with finding it. He sent his son Alexander to Paris to negotiate with French and American representatives, and the eventual result was that on behalf of the French government Barings and Hopes sold US government bonds worth $11.25 million. The business was of enormous size; ‘my nerves are equal to the operation’, Francis Baring reassured Hopes, but he added that ‘we all tremble about the magnitude of the American account’ (Barings archives, Northbrook MSS, A4). Later he confessed that ‘what I suffered can never be described and it completely overpowered my nerves for the first and I hope last time’ (ibid.).

The leading American house in London also acted as London banker for the Bank of the United States. Here again the close network of correspondents and friends which Baring so earnestly cultivated was vital. Thomas Willing, William Bingham's father-in-law and Barings' client at Philadelphia since 1774, was the bank's president and so its use of Baring's firm in making London payments, undertaking exchange transactions, and providing credits was seemingly inevitable.

Withdrawal from business

Baring aimed to strengthen his links with Hopes even further, through his son joining their partnership, but Alexander Baring could not be persuaded to comply. Baring's ultimate goal was to establish a house under his control based on both Barings and Hopes, which would straddle the North Sea, dominate government finance in Europe, and provide an enormously powerful base for its American connections. Alexander's reluctance compelled him ‘to abandon the colossal plan of one foot in England, the other in Holland’ (Barings archives, DEP193.17.1, Baring to Shelburne, 9 Oct 1802). It was ‘a sacrifice such as no head of a family ever made before’, he confided to Lansdowne, ‘but I must confess there is enough left for consolation’ (ibid.).

In 1803 Baring began his withdrawal from business when he gave up his entitlement to a share of his firm's profits. Much of his capital remained on loan; by the time of his death in 1810 he still provided £70,000 or about 17 per cent of the firm's resources. He stood down as partner in 1804, handing the reins to Charles Wall, the ‘principal manager’ according to Farrington, and his three eldest sons, Thomas Baring, Alexander Baring, and Henry Baring. In recognition of their assumption of leadership, in 1807 the nameplate of Sir Francis Baring & Co. was taken down and replaced by that of Baring Brothers.

Private wealth

Baring's accumulation of great wealth allowed him to diversify his pursuits in gentlemanly living. In 1790 he began to acquire property at Beddington in Surrey, based around Camden House, and in 1796 he bought Manor House, Lee, a relatively modest country house about 6 miles from central London, from his old friend Joseph Plaice, for £20,000. Land in Buckinghamshire was soon added at a cost of £16,000 and by 1800 his total investment in country estates exceeded £60,000. Yet more ambitious plans for life as a country landowner were fertilized; from 1801 he acquired from the duke of Bedford land and a great house at Stratton in Hampshire to create ‘the Kingdom of Stratton’ (Barings archives, Northbrook MSS, A21). By 1803 his expenditure had reached £150,000, partly funded through the sale of his Buckinghamshire land. In 1802 he transferred his London home from above his business in Devonshire Square to Hill Street in the West End.

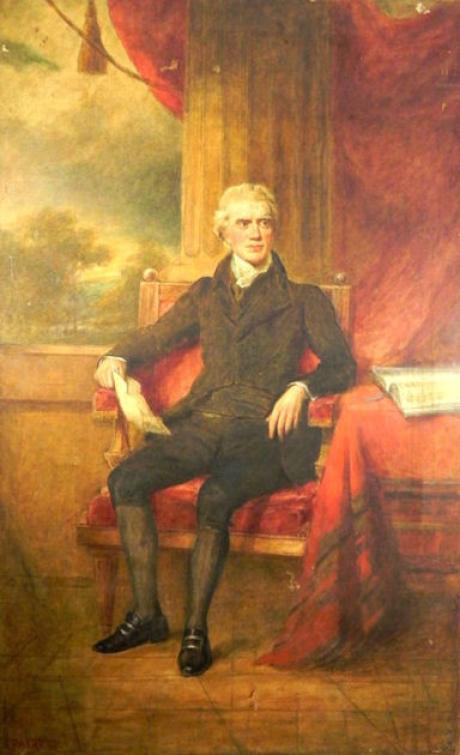

The architect George Dance was commissioned to remodel the house at Stratton, which was then filled with the finest furniture and best old masters. Baring's picture purchases had begun in 1795, when about £1500 was spent, and his expenditure grew apace after 1800; by 1808 he valued his acquisitions at £15,000. Dutch seventeenth-century masters were his particular passion but by 1804 he had ‘done with all except the very superior’; now only works by Rembrandt, Rubens, or Van Dyck ‘tempt me’ but ‘the first must not be too dark, nor the second indecent’ (Barings archives, Northbrook MSS, A4.3). He was a patron of Sir Thomas Lawrence, whom he summoned to Stratton in 1806 to paint a magisterial triple portrait of Baring with his two senior partners as a memorial to his business achievement.

Otherwise, Baring's distractions from business were few. As chairman from 1803 to 1810 of the Patriotic Fund administered by Lloyds of London, he worked for the welfare of Britons wounded or bereaved during the French wars. The mercantile community sought his help as referee in settling disputes, and as a trustee he gave distinguished service in settling the affairs of the leading London merchants, Boyd, Benfield & Co., which had crashed in 1799. He held the presidency of the London Institution from 1805 until his death. As a pamphleteer his output was modest, with works on the Commutation Act in 1786, on the Bank of England in 1797, and on the affairs of Walter Boyd in 1801.

Baring died on 11 September 1810 at Lee and was buried in the family vault at Stratton, Micheldever, on 20 September. He was survived by five sons and five daughters. His eldest son, Thomas, succeeded to the baronetcy and country estates; Thomas's son Francis was to enter political life and in 1866 was created Baron Northbrook. His second son, Alexander, succeeded him as senior partner and was later created Baron Ashburton for his political services. The third son, Henry, was also a partner, albeit an unremarkable one, while the other surviving sons, George and William, never rose to prominence.

The size of Baring's estate underlines his achievement: £175,000 was distributed among his children other than Thomas, who inherited the balance; his capital remaining in Barings amounted to almost £70,000; his Hampshire and Lee estates were valued at £400,000; and his pictures, jewels, and furniture were worth almost £30,000.

In the twenty-five years since 1777, Baring had transformed his firm into London's most powerful merchant banking house; by about 1786 he reckoned that it was ‘in a very flourishing situation, totally divested of moonshine’ (Barings archives, DEP193.17.1, Baring to Shelburne, n.d.). By 1800 a network of influential correspondents stretched across Europe; agencies were held for leading Boston and Philadelphia merchants; leadership in marketing British government debt was undisputed; Baring was a respected adviser to senior politicians; his leadership in the East India Company had provided influence in trade east of Africa; and, not least, important commissions had been won from foreign governments. Francis Baring was Barings, and he dominated management, provided most of the capital, and received the lion's share of the profits.

After Baring's death tributes included one from Lord Lansdowne, son of his political friend, who reckoned Baring was a ‘prince of merchants’. Another political ally, Lord Erskine, wrote: ‘he was unquestionably the first merchant in Europe; first in knowledge and talents and first in character and opulence’ (GM, 1st ser., 80, 1810, 293).

John Orbell DNB