signed and dated 1870 lower left

This lively, spirited dog breed is a true terrier. Bred in Manchester, England, for the common man's sports of rat killing and rabbit coursing, he's got game and he loves to show it. The Gentleman's Terrier (as he is known in Victorian England) is not a sparring dog but loves a good chase, making him a flyball and agility expert.

Though his looks suggest a miniature Doberman Pinscher or a large Miniature Pinscher, the Manchester Terrier is his own canine. A wee dog with a strong bark, he's got personality to burn: loyal, hearty, and a terrific watchdog who adores hanging out with his people. Among terriers, the Manchester is known to be one of the more well-mannered and responsive breeds and today spends his time as a terrific companion who can hold up his end of the conversation.

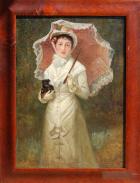

The history of sunshades goes back thousands of years, but it was during the Italian Renaissance of the 16th century that umbrellas and parasols were introduced to Europe. At first the items were large, used interchangeably, and generally carried by a servant to protect the wealthy from the elements and sun. Some were heavy (made of leather) but silk, paper, and cotton grew in popularity. During the 1700s parasols had already evolved into a woman’s fashion item, designed and decorated to match each promenade dress or walking suit, and was clearly defined as a sunshade; not for rain and snow. To make them collapsible developed around 1800, but ribs would break, paper tear, and the materials mildew if left damp. By the early Victorian era metallurgy had improved and alloy ribs were being used, nickel silver particularly popular. This type of thin strong metal was developed in Germany by craftsmen in an attempt to imitate the Chinese combination of copper, nickel and zinc, known as paktong.

At the beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign the parasols were quite plain, but by about 1850 tassels and frills grew in popularity. In each ensuing year the adornments became more ostentatious. If a dress had bows or flounces, the parasol could be adorned with the same decoration. This was a matter of taste, and ladies selected modest or extravagant versions for different circumstances, and based on what their income would allow. Of course it was only the wealthy who used parasols as a day-to-day accoutrement. A poor girl might have a simple parasol for church, or a Sunday afternoon stroll. It was during the 1850s the marquise parasol was developed, a style that tipped at the top, so a lady could hold the shaft straight and still shade her face well no matter the angle of the sun.

During this time many houses featured racks (two horizontal parallel arms) for placing open parasols and umbrellas high overhead in front and back halls; ideal for implements that didn’t close, could be damaged by constant opening and closing, or damp items. Parasol handles were usually straight, but some hooked examples exist. A plain parasol might have a wooden or metal pole with a bone handle, while the most expensive choices were of carved ivory shafts, decorated with inlaid jewels and gold banding. An in between version could be with carved horn and silver filigree accents. Throughout the Victorian era the handles grew longer, so “carriage” parasols were designed with a hinge in the middle to allow breakdown and ease of movement in tight spots.