inscribed and dated "ilfracombe 1863"

Tom and Laura Taylor and thence by descent

Hele Bay is a small village and beach just to the east of the town of Ilfracombe in North Devon, England. It is on the South West Coast Path. The small village of Hele is inland from the beach. Hele was listed in the Domesday Book of 1086 when the tenant-in-chief was Bishop Geoffrey of Coutances. There is a Grade II Listed corn mill at Hele Bay that dates back to around 1525.

The surface geology of north Devon is represented by a series of parallel bands of rock running roughly north-west to south-east (left). Hele is on the middle of the Ilfracombe Slates and is bordered to the east by the older Hangman Sandstone's and to the west by the younger Morte Slates. The eastern border runs along the eastern side of the valley of Combe Martin, the western border runs parallel from the coast at Lee Bay .

These sedimentary rocks were originally formed about 400 million years ago, mostly from mud and sand, with thin layers of limestone made from small coral reefs. North Devon then had a tropical desert climate and was under the sea just off a large continent south of the equator. About 300 million years ago the rocks were lifted and folded to form a chain of mountains to the north which may once have been as high as the Himalayas. In Hele the rocks slope down to the south by around 45 degrees; this can be seen quite clearly on Hele Beach ,

A layer of limestone about 15’ wide, lying nearly vertical, runs across the headlands of Rillage and Hillsborough. This was extensively quarried in the 19th century, particularly at Samson’s Beach and Joe Moon’s, for limeburning. The Rillage limestone is well known for its fossilised corals (right) which date from very early in the development of life on earth, when the first fish with vertebrates were beginning to appear (3).

A characteristic of the cliffs on Hele and Haggington Beach are long thin streaks of white quartz that were forced between the layers of rock under high pressure, presumably when they were folded. These intrusions are often associated with silver-lead deposits and although it is widely known that there were silver mines in Combe Martin, there are also traces of silver-lead mining around Berrynarbor and on Haggington Beach .

There is an early reference to smuggling in Ilfracombe in 1585, but smuggling really developed from the 1680’s when there were particularly high taxes on luxury imports. Sailing vessels began to use fore-and-aft rigging; which can sail nearer to the wind than square-rigging, and were consequently more manoeuvrable, enabling them to access remote and rocky bays. Smuggling was often associated with lime burning, since a vessel bringing coal or lime from Wales could meet a foreign ship in the Channel, purchase contraband, and land at a remote kiln where it could be secretly unloaded .

Hillsborough promontory juts into the sea between Ilfracombe harbour and Hele Bay. To the north and west are precipitous cliffs, with steep slopes to the east. To the south, the neck of the headland is about 300 metres wide and slopes down to the mainland. Across the neck are what appear to be three massive ramparts, enclosing the top of the headland, an area of about 25 acres.

Hillsborough is highly defensible, an excellent viewpoint to watch the Bristol Channel and is accessible from the sea; on either side are beaches (Rapparee and Hele) suitable for landing shallow-bottomed boats. Perhaps just as important, Hillsborough is visually very impressive, especially when seen from the approach along the Ilfracombe ridgeway. It is said to be one of the few places in England where, at certain times of the year, the sun can be seen rising from and setting into the sea, By local tradition it was a burial place of ancient Chiefs and this seems to be suggested by its name, which comes from Hele's-barrow (or burrow, which has the same meaning; not actually a burial place but a hill or hillock) .

The first Ordnance Survey map of 1809 (above left) shows what appears to be three ramparts running across the southern slope of Hillsborough. By local tradition they were thought to be a Roman encampment, but in 1879 Mrs Slade-King wrote "there are some doubtful remains of British earthworks on the land side of Hillsborough, but no evidence exists of any Roman military or domestic occupation". Ten years later, when the Ordnance Survey produced the first 1:2,500 scale map of Hele, the importance of the earthworks were evidently recognised, and they were surveyed in some detail (right). This is the only survey of the earthworks and it clearly shows two parallel ramparts, each with an inturned entrance, close together at the west but diverging at the east, where they have been disturbed by later limestone quarrying. The survey identified the third upper 'rampart' as a collapsed post-medieval boundary wall. The map shows a spring inside the ramparts - the tumulus marked at the summit of the hill is now thought to be natural. The two ramparts are shown outlined in red on this aerial photograph (below left) .

Workmen digging a trench on Hillsborough in 1937, to limit the spread of a gorse fire, found a small chamber in the side of the upper rampart. Unfortunately it was filled in before it could be properly investigated. The founding curator of Ilfracombe Museum, Mervyn Palmer, who took this photograph (below right), thought it may be a burial cist, in which case it is very important; if it dates from the Iron Age then it is the only such burial known in North Devon; but if it dates from the Bronze Age, then Hillsborough was occupied earlier than is presently thought .

In 1967Charles Whybrow published a study of several multivallate hillforts (i.e. those with more than one rampart) in North Devon. He noted the similarity between Hillsborough and other promontory forts in Cornwall; especially Embury Beacon near Hartland. He pointed out that the ramparts at Hillsborough were made by pulling material down from above; that the complex inturned entrances suggested a relatively late date, and that the ramparts diverge at the eastern end to form an enclosure that is overlooked by a natural mound. He did not guess the purpose of this enclosure, but it may have been designed to contain an enemy who had breached the lower rampart .

In 1970 Whybrow further proposed that Hillsborough was built by the Veneti, a warlike maritime tribe, thought to have fled Brittany c50 BC when Gaul was conquered by Julius Ceaser. It may have been abandoned before the Roman invasion c50 AD, as indicated by excavations in the late 1930's at Milber Down. However, in the early 1970's, a limited excavation at Embury Beacon, showed that the hillfort there had an earlier occupation, and in 1978 John Longhurst, then curator of Ilfracombe Museum, suggested that Hillsborough was similarly occupied between c300 BC and c50 AD .

Many hillforts are thought to have had a wooden palisade on top of the ramparts and large wooden entrance gates. Hillsborough, with two sets of palisades and gates, would have been an impressive sight indeed! There was probably some form of defensive boundary on the eastern side; perhaps a rampart, as suggested by the 1809 Ordnance Survey map; perhaps another palisade. The hillfort may have been occupied, possibly by the local tribal leader and his family; the most likely place is a level area just inside the inner rampart. This may have contained rectangular buildings similar to those found at Embury Beacon .

Hillsborough hillfort certainly seems to have been built to be defended and in times of trouble it could have provided refuge for many people and their animals. But it couldn’t have permanently supported all the people necessary for its construction and defence; there must have been several settlements nearby belonging to the same tribe. Perhaps there was one such settlement on Larkstone meadow, where traces of hut-circles are said to have been seen in the past. Another possible site is the top of small hill just inland of the Corn Mill, which has a spring nearby.

It is likely that Hillsborough was on a coastal ridgeway (left) which joined the ends of the Ilfracombe, Widmouth and Berrynarbor ridgeways and continued to Combe Martin, passing the hillfort at Newberry. Although both hillforts may not have been occupied at the same time, it is tempting to imagine that they could have signalled each other via lookouts on the top of Widmouth Hill and Haggington Hill .

It is likely that Hillsborough was on a coastal ridgeway (left) which joined the ends of the Ilfracombe, Widmouth and Berrynarbor ridgeways and continued to Combe Martin, passing the hillfort at Newberry. Although both hillforts may not have been occupied at the same time, it is tempting to imagine that they could have signalled each other via lookouts on the top of Widmouth Hill and Haggington Hill .

In 1962 and again in 1972 it was proposed to run a cable-car to the top of Hillsborough. Any such plans were permanently scrapped when the hill-fort was listed as a Scheduled Ancient Monument in 1978. The field investigator called it a fine promontory fort but added a note that he thought the alleged cist or fogou was an animal’s burrow. In the early 1980's a ski-run was proposed on the southern slopes, just below the ramparts; John Longhurst wrote a series of letters to determine the Scheduled boundary, which was unclear, and as a result it was established that the boundary extended south of the ramparts and the proposed ski-run was dropped .

When Hillsborough became a Nature Reserve in 1993 it was recommended that it be grazed, as it had been in the past, to prevent further damage to the earthworks by shrubs and rabbits, but this was strongly resisted by local people who did not want to see fences erected. In 1996 Aileen Fox wrote that "regrettably the hillfort defences are badly overgrown". In 2000 Tanya Walls noted a possible previously unrecorded earthwork at Beacon Point and again recommended that the hillfort be grazed. She suggested that a proper surface and geophysical survey be carried out, but referred to an earlier visit by English Heritage which concluded that the site was already too overgrown to conduct a proper survey. It is a great pity that one of Ilfracombe's most important historical treasures is in such neglect

Smuggling was common in north Devon in the 18th and early 19th centuries, although recorded information is understandably rare. Smugglers were known to have used Lee, Ilfracombe, Heddon’s Mouth, Watermouth Cove and Morte. Some of the smuggling operations were clearly considerable; in 1785 a 96 gallon cask [sic] of rum was found at Watermouth Cove and in 1801 224 gallons of gin and 164 gallons of brandy were found on the foreshore near Ilfracombe. It seems that everyone was involved; in 1783 all the Ilfracombe pilot boats were suspected of smuggling and one, the Cornwall, was seized and cut up into three parts. An Ilfracombe Collector from 1804-1824, Thomas Rudd, was father in law to a known smuggler, Cooke, who was never caught. In 1825 the richest man in Combe Martin, John Dovell, was prosecuted for handling smuggled goods .

The most infamous smuggler in north Devon was Thomas Benson, who in 1747 became MP for Barnstaple. The following year he was granted a lease on Lundy and entered into contract with the Government to carry convicts abroad. However, he landed them on Lundy instead to run his smuggling operation. He became over confident and was fined for smuggling and stripped of his office. He didn’t pay and his lands in Bideford were seized. To recover his losses he persuaded the Captain of the Nightingale to fire it for the insurance, but the plan was discovered and he fled to Portugal. The poor Captain was tried and executed in 1754.

Far worse than smugglers were the wreckers, who would lure a ship onto the rocks with a misplaced light and then plunder anything of value. Salvage couldn’t be kept if there was even one survivor and Elizabeth Berry from Morthoe was said to be known for holding down drowning men with a pitchfork (she was arrested for plundering the William and Jane in 1850 and given 21 days hard labour). The William Wilberforce was said to have been lured onto the rocks at Lee in 1842 by tying a lantern to a donkey’s tail, but there is no evidence to support this. Wrecking is said to have ceased after the Rev. Charles Crump wrote an account of the 1850 alleged wrecking of the Thomas Crisp, entitled the Morte Stone; and work started on a lighthouse at Bull Point in 1878 .

There are said to have been wreckers and smugglers in Hele. There is a local legend that the Granada was wrecked in Hele Bay in 1663 by Alexander Oatway, a tenant of Chambercombe, and that the skeleton of a young woman was found in a hidden room at Chambercombe in 1865, supposedly from Oatway's tenancy. There is a hidden room, to the right of the tallest chimney in this engraving from before 1840 (left), but the legend of the skeleton and the smuggler Oatway is almost certainly from an anonymous story The Call of Chambercombe, published in 1865, which ironically tells how Alexander's son, William, found a lady barely alive on Hele Beach after a shipwreck and hid her at Chambercombe so that he could keep her money and jewels. But he realises, as she dies, that she was his own daughter (5).

There are said to have been wreckers and smugglers in Hele. There is a local legend that the Granada was wrecked in Hele Bay in 1663 by Alexander Oatway, a tenant of Chambercombe, and that the skeleton of a young woman was found in a hidden room at Chambercombe in 1865, supposedly from Oatway's tenancy. There is a hidden room, to the right of the tallest chimney in this engraving from before 1840 (left), but the legend of the skeleton and the smuggler Oatway is almost certainly from an anonymous story The Call of Chambercombe, published in 1865, which ironically tells how Alexander's son, William, found a lady barely alive on Hele Beach after a shipwreck and hid her at Chambercombe so that he could keep her money and jewels. But he realises, as she dies, that she was his own daughter (5).

There are always local legends regarding smugglers caves and tunnels. There is said to have been a tunnel from Watermouth Cove to the nearby Castle, and the Tunnels in Ilfracombe are said to have originally been a smugglers cave. There is also a legend of a tunnel from Chambercombe Manor to Hele beach. The Call of Chambercombe has a chapter called The Cave at Hele Bay, where wreckers hid their booty; but it is not like any local cave and there is no tunnel (although some of the story does take place in a Cornish mine). The first mention of a tunnel in Hele is from the Ilfracombe Chronicle of 1874, which refers to "a subterranean passage between the village and Chambercombe which was used by the wreckers". In 1888, in an article on smuggling, an 'old man' claimed that when he was a boy, he heard of a smuggler's tunnel from Hele Beach to an old well at Chambercombe. Another article from 1933 quoted Nathaniel Lewis, who lived in Hele, as saying that the tunnel led to Rapparee Cove. In 1976, Lilian Wilson wrote that the tunnel, now collapsed, led to a ledge high up in Samson's Cave, accessible only by ladder (6).

By local tradition, Samson’s Cave and Samson's Bay were named after a local smuggler called Samson or Sampson (or is it coincidence that the Coastguard cottages were built above here in the 1930’s ?). But smuggler's didn't often use caves or tunnels, preferring the open where they could escape. The other local caves, Joe Moon's and Tom Norman's Hole, are named after the quarryman or miners that made them; Samson's probably has a similar origin. There are actually five caves in the bay and it is not clear which one is Samson's; the 1889 Ordnance Survey map shows Samson's Cave on the eastern side, but also Samson's Caves on the western side. One of the two western caves, furthest from the sea, does however match Lilian Wilson's description; just inside, on the left, is a high gully at the top of which is a ledge, largely obscured, and very difficult to reach.

At Chambercombe, part of what appears to have been a chimney breast, contains a curious hidden vertical shaft, with an iron ladder, leading up into the roof. The shaft is filled to ground level but it is said that early in the 20th century it led down into a tunnel, blocked after some 20-30 paces. The shaft's stones are unfaced and it would have been useless for hiding smuggled goods, there being barely enough room to climb the rungs. If not just an architectural accident, capitalised by the addition of a ladder, then it may have once led to a priest hole (but an iron ladder ?). Many old houses have hiding places that were made in times of religious persecution. Perhaps the shaft led to a priest hole in the roof, or underground. If there really was a tunnel, it could have been a route leading to the nearby stream, some 40-50m away, where a small ravine 3-4m deep provides good cover for escape. This is much more likely than a tunnel from Chambercombe to Samson's; such a tunnel would have to be two kilometres long and pass under three streams. Besides, it would be far less trouble, and just as effective at concealment, to simply walk up the stream from Hele Beach.

There are persistent stories of Hele being associated with smugglers, and they are not all in the distant past. The 1933 Ilfracombe Chronicle article says that there was smuggling at Chambercombe when Nicholas Lewis was alive; it also refers to Jan White's path, and to a Bill Stephens and John Wilkey, who apparently tried to waylay a smuggler's wagon en-route from Chambercombe to South Molton, but were bribed off with silken scarves. Nicholas Lewis lived in Hele at the time of the first Census in 1841, as did a William Stevins, and a John White lived at Widmouth farm. In 1851 a John Wilkey lived in Hele and Chambercombe was tenanted by John Robins; this is a photograph of his son, John Robins (right), he certainly looks the part of a smuggler! Coincidently (?) one of his workmen may have been called John Oatway.

There are persistent stories of Hele being associated with smugglers, and they are not all in the distant past. The 1933 Ilfracombe Chronicle article says that there was smuggling at Chambercombe when Nicholas Lewis was alive; it also refers to Jan White's path, and to a Bill Stephens and John Wilkey, who apparently tried to waylay a smuggler's wagon en-route from Chambercombe to South Molton, but were bribed off with silken scarves. Nicholas Lewis lived in Hele at the time of the first Census in 1841, as did a William Stevins, and a John White lived at Widmouth farm. In 1851 a John Wilkey lived in Hele and Chambercombe was tenanted by John Robins; this is a photograph of his son, John Robins (right), he certainly looks the part of a smuggler! Coincidently (?) one of his workmen may have been called John Oatway.

Smuggling became less common during the 19th century. One of the last major occurrences near Ilfracombe was the smack Lively, who lost her boom in a storm in October 1831 off Lundy, was seized by Custom's with 300 tubs of brandy on board and broken up into three parts. According to articles in the Ilfracombe Chronicle of 1888 and 1913, she was first found by some Ilfracombe vessels, who offered help but wanted more than the smuggler's were willing to pay. They returned to port, and soon after, a Customs ship put out and apprehended the Lively, giving rise to the expression Combe Sharks and the following song (7):-

"Come all you shipmasters, I bid you beware!

When outside ‘Combe harbour, I’d have you take care;

If long in that roadstead, you forced are to lie,

Be sure you don’t let those bold Pirates draw nigh.

CHORUS: Sing Brandy hi O !

They’ll kiss you like Judas, and will you betray,

Then into ‘Combe harbour will force you straightway

Unless fifty pounds or your cargoe half share

You give them, your body and soul they’ll ensnare.

CHORUS: Sing Brandy hi O !"

The smugglers still had plenty of local support, however, since it appears that an effigy of one of the men who reported them was burnt in public

Tom Taylor (19 October 1817 – 12 July 1880) was an English dramatist, critic, biographer, public servant, and editor of Punch magazine. Taylor had a brief academic career, holding the professorship of English literature and language at University College, London in the 1840s, after which he practised law and became a civil servant. At the same time he became a journalist, most prominently as a contributor to, and eventually editor of Punch.

In addition to these vocations, Taylor began a theatre career and became best known as a playwright, with up to 100 plays staged during his career. Many were adaptations of French plays, but these and his original works cover a range from farce to melodrama. Most fell into neglect after Taylor's death, but Our American Cousin (1858), which achieved great success in the 19th century, remains famous as the piece that was being performed in the presence of Abraham Lincoln when he was assassinated in 1865.

Early years

Taylor was born into a newly wealthy family at Bishopwearmouth, a suburb of Sunderland, in north-east England. He was the second son of Thomas Taylor (1769–1843) and his wife, Maria Josephina, née Arnold (1784–1858). His father had begun as a labourer on a small farm in Cumberland and had risen to become co-owner of a flourishing brewery in Durham. After attending the Grange School in Sunderland, and studying for two sessions at the University of Glasgow, Taylor became a student of Trinity College, Cambridge in 1837, was elected to a scholarship in 1838, and graduated with a BA in both classics and mathematics. He was elected a fellow of the college in 1842 and received his MA degree the following year.

Taylor left Cambridge in late 1844 and moved to London, where for the next two years he pursued three careers simultaneously. He was professor of English language and literature at University College, London, while at the same time studying to become a barrister, and beginning his life's work as a writer. Taylor was called to the bar of the Middle Temple in November 1846. He resigned his university post, and practised on the northern legal circuit until he was appointed assistant secretary of the Board of Health in 1850. On the reconstruction of the board in 1854 he was made secretary, and on its abolition in 1858 his services were transferred to a department of the Home Office, retiring on a pension in 1876.

Writer

Taylor owed his fame and most of his income not to his academic, legal or government work, but to his writing. Soon after moving to London, he obtained remunerative work as a leader writer for the Morning Chronicle and the Daily News. He was also art critic for The Times and The Graphic for many years. He edited the Autobiography of B. R. Haydon (1853), the Autobiography and Correspondence of C. R. Leslie, R.A. (1860) and Pen Sketches from a Vanished Hand, selected from papers of Mortimer Collins, and wrote Life and Times of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1865). With his first contribution to Punch, on 19 October 1844, Taylor began a thirty-six year association with the magazine, which ended only with his death. During the 1840s he wrote on average three columns a month; in the 1850s and 1860s this output doubled. His biographer Craig Howes writes that Taylor's articles were generally humorous commentary or comic verses on politics, civic news, and the manners of the day. In 1874 he succeeded Charles William Shirley Brooks as editor.

Taylor also established himself as a playwright and eventually produced about 100 plays. Between 1844 and 1846, the Lyceum Theatre staged at least seven of his plays, including extravanzas written with Albert Smith or Charles Kenney, and his first major success, the 1846 farce To Parents and Guardians. The Morning Post said of that piece, "The writing is admirable throughout – neat, natural and epigrammatic". It was as a dramatist that Taylor made the most impression – his biographer in the Dictionary of National Biography (DNB) wrote that in writing plays Taylor found his true vocation. In thirty-five years he wrote more than seventy plays for the principal London theatres.

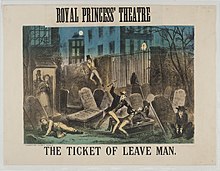

A substantial portion of Taylor's prolific output consisted of adaptations from the French or collaborations with other playwrights, notably Charles Reade. Some of his plots were adapted from the novels of Charles Dickens or others. Many of Taylor's plays were extremely popular, such as Masks and Faces, an extravaganza written in collaboration with Reade, produced at the Haymarket Theatre in November 1852. It was followed by the almost equally successful To Oblige Benson (Olympic Theatre, 1854), an adaptation from a French vaudeville. Others mentioned by the DNB are Plot and Passion (1853), Still Waters Run Deep (1855) and The Ticket-of-Leave Man (based on Le Retour de Melun by Édouard Brisebarre and Eugène Nus), a melodrama produced at the Olympic in 1863.Taylor also wrote a series of historical dramas (many in blank verse), including The Fool’s Revenge (1869), an adaption of Victor Hugo's Le roi s'amuse (also adapted by Verdi as Rigoletto), 'Twixt Axe and Crown (1870), Jeanne d'arc (1871), Lady Clancarty (1874) and Anne Boleyn (1875). The last of these, produced at the Haymarket in 1875, was Taylor's penultimate piece and only complete failure. In 1871 Taylor supplied the words to Arthur Sullivan's dramatic cantata, On Shore and Sea.

Like his colleague W. S. Gilbert, Taylor believed that plays should be readable as well as actable; he followed Gilbert in having copies of his plays printed for public sale. Both authors did so at some risk, because it made matters easy for American pirates of their works in the days before international copyright protection. Taylor wrote, "I have no wish to screen myself from literary criticism behind the plea that my plays were meant to be acted. It seems to me that every drama submitted to the judgment of audiences should be prepared to encounter that of readers".

Many of Taylor's plays were extremely popular, and several survived into the 20th century, although most are largely forgotten today. His Our American Cousin (1858) is now remembered chiefly as the play Abraham Lincoln was attending when he was assassinated, but it was revived many times during the 19th century with great success. It became celebrated as a vehicle for the popular comic actor Edward Sothern, and after his death, his sons, Lytton and E. H. Sothern, took over the part in revivals.

Howes records that Taylor was described as "of middle height, bearded [with] a pugilistic jaw and eyes which glittered like steel". Known for his remarkable energy, he was a keen swimmer and rower, who rose daily at five or six and wrote for three hours before taking an hour's brisk walk from his house in Wandsworth to his Whitehall office.

Some, like Ellen Terry, praised Taylor's kindness and generosity; others, including F. C. Burnand, found him obstinate and unforgiving. Terry wrote of Taylor in her memoirs:

Most people know that Tom Taylor was one of the leading playwrights of the 'sixties as well as the dramatic critic of The Times, editor of Punch, and a distinguished Civil Servant, but to us he was more than this. He was an institution! I simply cannot remember when I did not know him. It is the Tom Taylors of the world who give children on the stage their splendid education. We never had any education in the strict sense of the word yet through the Taylors and others, we were educated.

Terry's frequent stage partner, Henry Irving said that Taylor was an exception to the general rule that it was helpful, even though not essential, for a dramatist to be an actor to understand the techniques of stagecraft: "There is no dramatic author who more thoroughly understands his business".

In 1855 Taylor married the composer, musician and artist Laura Wilson Barker (1819–1905). She contributed music to at least one of his plays, an overture and entr'acte to Joan of Arc (1871), and harmonisations to his translation Ballads and Songs of Brittany (1865). There were two children: the artist John Wycliffe Taylor (1859–1925) and Laura Lucy Arnold Taylor (1863–1940). Taylor and his family lived at 84 Lavender Sweep, Battersea, where they held Sunday musical soirees. Celebrities who attended included Lewis Carroll, Charles Dickens, Henry Irving, Charles Reade, Alfred Tennyson, Ellen Terry and William Makepeace Thackeray.

Taylor died suddenly at his home in 1880 at the age of 62 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery. After his death, his widow retired to Coleshill, Buckinghamshire, where she died on 22 May 1905.