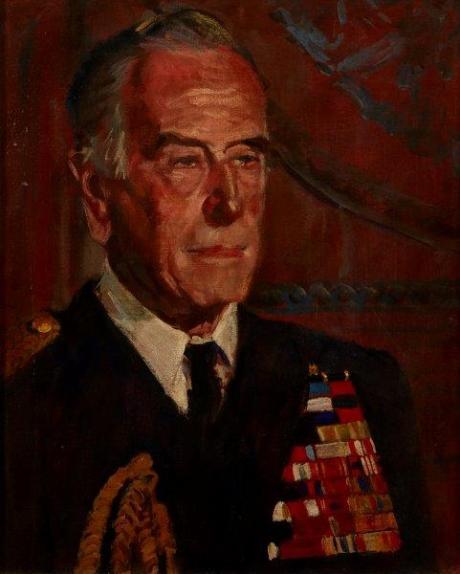

Sothebys Sale, Modern British and Irish Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, March 8, 1995 , Lot 197

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas, first Earl Mountbatten of Burma (1900–1979), naval officer and viceroy of India, was born at Frogmore House, Windsor, on 25 June 1900 as Prince Louis of Battenberg, the younger son and the youngest of the four children of Prince Louis Alexander of Battenberg (1854–1921) and his wife, Princess Victoria (1863–1950), the daughter of Louis IV of Hesse. Prince Louis Alexander, himself head of a cadet branch of the house of Hesse, was brother-in-law to Queen Victoria's daughter Princess Beatrice; his wife was Victoria's granddaughter. By both father and mother, therefore, Prince Louis was closely connected with the British royal family. One sister, Alice, married Prince Andrew of Greece, and the other, Louise, married King Gustav VI of Sweden.

Early life

Prince Louis, Dickie as he was known from childhood, was educated as befitted the son of a senior naval officer—a conventional upbringing varied by holidays with his German relatives or with his aunt, the tsarina, in Russia. At Locker's Park School in Hertfordshire he was praised for his industry, enthusiasm, sense of humour, and modesty—the first two at least being characteristics conspicuous throughout his life. From there in May 1913 he entered the Royal Naval College, Osborne, as fifteenth out of eighty-three, a respectable if unglamorous position which he more or less maintained during his eighteen months there. Towards the end of his stay his father, now first sea lord, was hounded from office because of his German ancestry. This affected young Prince Louis deeply, though a contemporary recalls him remarking nonchalantly: 'It doesn't really matter very much. Of course I shall take his place' (Ziegler, 36). Certainly his passionate ambition owed something to his desire to avenge his father's disgrace.

In November 1914 Prince Louis moved on to Dartmouth. Although he never shone athletically, or impressed himself markedly on his contemporaries, his last years of education showed increasing confidence and ability, and at Keyham, the Royal Naval College at Devonport where he did his final course, he came first out of seventy-two. In July 1916 he was assigned as a midshipman to the Lion, the flagship of Admiral Sir David Beatty. His flag captain, Roger Backhouse, described him as 'a very promising young officer' (Broadlands MSS, O.5. ‘naval appointments’, 27 Nov 1916), but his immediate superior felt he lacked the brilliance of his elder brother George —a judgement which Prince Louis himself frequently echoed. The Lion saw action in the eight months Prince Louis was aboard but suffered no damage, and by the time he transferred to the Queen Elizabeth in February 1917 the prospects of a major naval battle seemed remote. Prince Louis served briefly aboard the submarine K6—'the happiest month I've ever spent in the service' (Broadlands MSS, Mountbatten to Lady Milford Haven, 22 Jan 1918, vol. 7)—and visited the western front, but his time on the Queen Elizabeth was uneventful and he was delighted to be posted in July 1918 as first lieutenant on one of the P-boats, small torpedo boats designed primarily for anti-submarine warfare. It was while he was on the Queen Elizabeth that his father, in common with other members of the royal family, abandoned his German title and was created marquess of Milford Haven, with the family name of Mountbatten. His younger son was known henceforth as Lord Louis Mountbatten.

At the end of 1919 Mountbatten was one of a group of naval officers sent to widen their intellectual horizons at Cambridge. During his year at Christ's College (of which he became an honorary fellow in 1946) he acquired a taste for public affairs, regularly attending the union and achieving the distinction, remarkable for someone in his position, of being elected to the committee. Through his close friend Peter Murphy he also opened his mind to radical opinions—'We all thought him rather left-wing' (Broadlands MSS, The life and times of Lord Mountbatten, post production scripts, programme 2, reel 3, p. 5), said the then president of the union, Geoffrey Shakespeare.

While still at Cambridge, Mountbatten was invited by his cousin the prince of Wales to attend him on the forthcoming tour of Australasia in the Renown. Mountbatten's roles were those of unofficial diarist, dogsbody, and, above all, companion to his sometimes moody and disobliging cousin. These he performed admirably—'you will never know', wrote the prince to Lord Milford Haven, 'what very great friends we have become, what he has meant and been to me on this trip' (Broadlands MSS, prince of Wales to Lord Milford Haven, 19 Sept 1920, vol. 8a). His reward was to be invited to join the next royal tour to India and Japan in the winter of 1921–2, a journey that doubly marked his life in that in India he learned to play polo and became engaged to Edwina Cynthia Annette (1901–1960) , the daughter of Wilfrid William Ashley.

Edwina Ashley was descended from the third Viscount Palmerston and the earls of Shaftesbury, while her maternal grandfather was the immensely rich Sir Ernest Cassel, a friend and financial adviser to Edward VII. At Cassel's death in 1921 his granddaughter inherited some £2.3 million, and eventually also a palace on Park Lane, Classiebawn Castle in Ireland, and the Broadlands estate at Romsey in Hampshire. They were married on 18 July 1922. The union of two powerful and fiercely competitive characters was never wholly harmonious and sometimes caused unhappiness to both partners. On the whole, however, it worked well and they established a formidable partnership at several stages of their lives. They had two daughters.

Naval officer

Early in 1923 Mountbatten joined the Revenge. For the next fifteen years his popular image was that of a playboy. Fast cars, speedboats, polo, were his delights; above all the last, about which he wrote the classic Introduction to Polo (1931) by Marco. Yet nobody who knew his work could doubt his essential seriousness. 'This officer's heart and soul is in the Navy', reported the captain of the Revenge, 'No outside interests are ever allowed to interfere with his duties' (Broadlands MSS, O.5. ‘naval appointments’, 1 Aug 1924). His professionalism was proved beyond doubt when he selected signals as his speciality and passed out top of the course in July 1925. As assistant fleet wireless officer (1927–8) and fleet wireless officer (1931–3) in the Mediterranean, and at the signals school at Portsmouth in between, he won a reputation for energy, efficiency, and inventiveness. He raised the standard of signalling in the Mediterranean Fleet to new heights and was known, respected, and almost always liked by everyone under his command.

In 1932 Mountbatten was promoted commander and in April 1934 took over the Daring, a new destroyer of 1375 tons. After only a few months, however, he had to exchange her for an older and markedly inferior destroyer, the Wishart. Undiscomfited, he set to work to make his ship the most efficient in the Mediterranean Fleet. He succeeded and Wishart was cock of the fleet in the regatta of 1935. It was at this time that he perfected the 'Mountbatten station-keeping gear', an ingenious device which was adopted by the Admiralty for use in destroyers but which never really proved itself in wartime.

Enthusiastically recommended for promotion, Mountbatten returned to the naval air division of the Admiralty. He was prominent in the campaign to recapture the Fleet Air Arm from the Royal Air Force, lobbying Winston Churchill, Sir Samuel Hoare, and A. Duff Cooper with a freedom unusual among junior officers. He vigorously applauded Cooper's resignation over the Munich agreement and maintained a working relationship with Anthony Eden and the fourth marquess of Salisbury in their opposition to appeasement. More practically he was instrumental in drawing the Admiralty's attention to the merits of the Oerlikon gun, the adoption of which he urged vigorously for more than two years. It was during this period that he also succeeded in launching the Royal Naval Film Corporation, an organization designed to secure the latest films for British sailors at sea.

The abdication crisis caused Mountbatten much distress but left him personally unscathed. Some time earlier he had hopefully prepared for the prince of Wales a list of eligible protestant princesses, but by the time of the accession he had little influence left. He had been Edward VIII's personal naval aide-de-camp, and in February 1937 George VI appointed him to the same position, simultaneously appointing him to the GCVO.

Since the autumn of 1938 Mountbatten had been contributing ideas to the construction at Newcastle of a new destroyer, the Kelly. In June 1939 he took over as captain and Kelly was commissioned by the outbreak of war. On 20 September she was joined by her sister ship Kingston, and Mountbatten became captain (D) of the fifth destroyer flotilla.

Mountbatten was not markedly successful as a wartime destroyer captain. In surprisingly few months at sea he almost capsized in a high sea, collided with another destroyer, and was mined once, torpedoed twice, and finally sunk by enemy aircraft. In most of these incidents he could plead circumstances beyond his control, but the consensus of professional opinion is that he lacked ‘sea sense’, the quality that ensures a ship is doing the right thing in the right place at the right time. Nevertheless he acted with immense panache and courage and displayed such qualities of leadership that, when Kelly was recommissioned after several months refitting, an embarrassingly large number of her former crew clamoured to rejoin. When he took his flotilla into Namsos in March 1940 to evacuate Adrian Carton de Wiart and several thousand allied troops, he conducted the operation with cool determination. The return of Kelly to port in May, after ninety-one hours in tow under almost constant bombardment and with a 50 foot hole in the port side, was an epic of fortitude and seamanship. It was feats such as this that caught Churchill's imagination and thus altered the course of Mountbatten's career.

In the spring of 1941 the Kelly was dispatched to the Mediterranean. Placed in an impossible position, Admiral Sir A. B. Cunningham in May decided to support the army in Crete, even though there was no possibility of air cover. The Kashmir and the Kelly were attacked by dive-bombers on 23 May and soon sunk. More than half the crew of Kelly was lost and Mountbatten escaped only by swimming from under the ship as it turned turtle. The survivors were machine-gunned in the water but were picked up by the Kipling. The Kelly lived on in the film In which we Serve, a skilful piece of propaganda by Noël Coward, which was based in detail on the achievements of Mountbatten and his ship. Mountbatten was now appointed to command the aircraft-carrier Illustrious, which had been severely damaged and sent for repair to the United States. In October he flew to America to take over his ship and pay a round of visits. He established many useful contacts and made a considerable impression on the American leadership: 'he has been a great help to all of us, and I mean literally ALL', wrote Admiral Stark to Sir A. Dudley Pound (Ziegler, 152). Before the Illustrious was ready, however, Mountbatten was called home by Churchill to take charge of combined operations. His predecessor, Sir Roger Keyes, had fallen foul of the chiefs of staff, and Mountbatten was initially appointed only as chief adviser. In April 1942, however, he became chief of combined operations, with the acting rank of vice-admiral, lieutenant-general, and air marshal and with de facto membership of the chiefs of staff committee. This phenomenally rapid promotion earned him some unpopularity, but on the whole the chiefs of staff gave him full support.

Combined operations

'You are to give no thought for the defensive. Your whole attention is to be concentrated on the offensive', Churchill told Mountbatten (Ziegler, 156). His duties fell into two main parts: to organize raids against the European coast designed to raise morale, harass the Germans, and achieve limited military objectives; and to prepare for an eventual invasion. The first responsibility, more dramatic though less important, gave rise to a multitude of raids involving only a handful of men and a few more complex operations such as the costly but successful attack on the dry dock at St Nazaire. Combined operations were responsible for planning such forays, but their execution was handed over to the designated force commander, a system which led sometimes to confusion.

The ill results of divided responsibilities were particularly apparent in the Dieppe operation of August 1942. Dieppe taught the allies valuable lessons for the eventual invasion and misled the Germans about their intentions, but the price paid in lives and material was exceedingly, probably disproportionately, high. For this Mountbatten, ultimately in charge of planning the operation, must accept some responsibility. Nevertheless the errors which both British and German analysts subsequently condemned—the adoption of frontal rather than flank assault, the selection of relatively inexperienced Canadian troops for the assault, the abandonment of any previous air bombardment, and the failure to provide the support of capital ships—were all taken against his advice or over his head. Certainly he was not guilty of the blunders which Lord Beaverbrook in particular attributed to him.

Some later commentators have tried to establish that Mountbatten bore almost sole responsibility for the débâcle and that the decision to remount the operation after its initial cancellation was taken on his own authority and without reference to the chiefs of staff. It is true that the minutes of the chiefs of staff committee do not record any decision to relaunch the attack on Dieppe, but this is unsurprising given the extreme secrecy of the project. The minutes equally contain no reference to the race to produce an atom bomb, yet discussion on the subject undoubtedly occurred. All the chiefs, for differing reasons, supported the raid, and Churchill in his memoirs specifically refers to a meeting at which he went through the plans with Mountbatten and Alan Brooke and gave them his full approval.

Where Mountbatten can properly be blamed is over the provision of intelligence. He did not know, and should have known, that between the date of the aborted first raid and 19 August all the channel ports had been reinforced, fortifications strengthened, superior troops brought in, and new gun emplacements built. The targets with which destroyers could possibly have coped in July were impregnable to such attack a month later. The need for the support of a battleship or aerial bombardment, strong even at the earlier date, was irresistible by the time the landings took place. The intelligence service most directly to blame was that of combined operations.

When it came to preparation for invasion, Mountbatten's energy, enthusiasm, and receptivity to new ideas showed to great advantage. His principal contribution was to see clearly what is now obvious but was then not generally recognized, that successful landings on a fortified enemy coast called for an immense range of specialized equipment and skills. To secure an armada of landing craft of different shapes and sizes, and to train the crews to operate them, involved a diversion of resources, both British and American, which was vigorously opposed in many quarters. The genesis of such devices as Mulberry (the floating port) and Pluto (pipeline under the ocean) is often hard to establish, but the zeal with which Mountbatten and his staff supported their development was a major factor in their success. Mountbatten surrounded himself with a team of talented if sometimes maverick advisers—Professor J. D. Bernal, Geoffrey Pyke, Solly Zuckerman—and was ready to listen to anything they suggested. Sometimes this led him into wasteful extravagances—as in his championship of the iceberg/aircraft carrier Habbakuk—but there were more good ideas than bad. His contribution to D-day was recognized in the tribute paid him by the allied leaders shortly after the invasion: 'we realize that much of … the success of this venture has its origins in developments effected by you and your staff' (Ziegler, 215).

Mountbatten's contribution to the higher strategy is less easy to establish. He himself always claimed responsibility for the selection of Normandy as the invasion site rather than the Pas-de-Calais. Certainly when operation Sledgehammer, the plan for a limited re-entry into the continent in 1942, was debated by the chiefs of staff, Mountbatten was alone in arguing for the Cherbourg peninsula. His consistent support of Normandy may have contributed to the change of heart when the venue of the invasion proper was decided. In general, however, Alan Brooke and the other chiefs of staff resented Mountbatten's ventures outside the field of his immediate interests and he usually confined himself to matters directly concerned with combined operations.

Mountbatten's headquarters, COHQ, indeed the whole of his command, was sometimes criticized for its lavishness in personnel and encouragement of extravagant ideas. Mountbatten was never economical, and waste there undoubtedly was. Nevertheless he built up at great speed an organization of remarkable complexity and effectiveness. By April 1943 combined operations command included 2600 landing craft and more than 50,000 men. He almost killed himself in the process, for in July 1942 he was told by his doctors that he would die unless he worked less intensely. A man with less imagination who played safe could never have done as much. It was Alan Brooke, initially unenthusiastic about his elevation, who concluded: 'His appointment as Chief of Combined Operations … was excellent, and he played a remarkable part as the driving force and main-spring of this organization. Without his energy and drive it would never have reached the high standard it achieved' (A. Bryant, The Turn of the Tide, 1957, 321).

Mountbatten arrived at the Quebec conference in August 1943 as chief of combined operations; he left as acting admiral and supreme commander designate, south-east Asia. 'He is young, enthusiastic and triphibious' (TNA: PRO, PREM, 9 Aug 1943), Churchill telegraphed C. R. Attlee, but though the Americans welcomed the appointment enthusiastically, he was selected only after half a dozen candidates had been eliminated for various reasons.

Supreme commander, south-east Asia

Mountbatten took over a command where everything had gone wrong. The British and Indian army, ravaged by disease and soundly beaten by the Japanese, had been chased out of Burma. A feeble attempt at counter-attack in the Arakan peninsula had ended in disaster. Morale was low, air support inadequate, communications within India slow and uncertain. There seemed little to oppose the Japanese if they decided to resume their assault. Yet before Mountbatten could concentrate on his official adversaries he had to resolve the anomalies within his own command.

Most conspicuous of these was General Stilwell. As well as being deputy supreme commander, Stilwell was chief of staff to Chiang Kai-shek, and his twin roles inevitably involved conflicts of interest and loyalty. A superb leader of troops in the field but cantankerous, Anglophobe, and narrow-minded, Stilwell would have been a difficult colleague in any circumstances. In south-east Asia, where his preoccupation was to reopen the road through north Burma to China, he proved almost impossible to work with. But Mountbatten also found his relationship difficult with his own, British, commanders-in-chief, in particular the naval commander, Sir James Somerville. Partly, this arose from differences of temperament; more importantly it demonstrated a fundamental difference of opinion about the supreme commander's role. Mountbatten, encouraged by Churchill and members of his own entourage, believed that he should operate on the MacArthur model, with his own planning staff, consulting his commanders-in-chief but ultimately instructing them on future operations. Somerville, General Sir G. J. Giffard, and Air Marshal Sir R. E. C. Peirse, on the other hand, envisaged him as a chairman of committee, operating like Eisenhower and working through the planning staffs of the commanders-in-chief. The chiefs of staff in London proved reluctant to rule categorically on the issue, but Mountbatten eventually abandoned his central planning staff, and the situation was further eased when Somerville was replaced by Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser.

Mountbatten defined the three principal problems facing him as being those of monsoon, malaria, and morale. His determination that allied troops must fight through the monsoon, though of greater psychological than military significance, undoubtedly assisted the eventual victories of the Fourteenth Army. In 1943, for every casualty evacuated because of wounds, there were 120 sick, and Mountbatten, by his emphasis on hygiene and improved medical techniques, can claim much credit for the vast improvement over the next year. But it was in the transformation of the soldiers' morale that he made his greatest contribution. By publicity, propaganda, and the impact of his personality he restored their pride in themselves and gave them confidence that they could defeat the Japanese.

Deciding what campaign they were to fight proved difficult. Mountbatten, with Churchill's enthusiastic backing, envisaged a bold amphibious strategy which would bypass the Burmese jungles and strike through the Andaman Islands to Rangoon or, more ambitious still, through northern Sumatra towards Singapore. The Americans, however, who would have provided the material resources for such adventures, nicknamed South-East Asia command (SEAC) 'Save England's Asiatic colonies' and were suspicious of any operation which seemed designed to this end. They felt that the solitary justification for the Burma campaign was to restore land communications with China. The ambitious projects with which Mountbatten had left London withered as his few landing craft were withdrawn. A mission he dispatched to London and Washington returned empty-handed. 'You might send out the waxwork which I hear Madame Tussauds has made', wrote Mountbatten bitterly to his friend Charles Lambe, 'it could have my Admiral's uniform and sit at my desk … as well as I could' (Ziegler, 265).

It was the Japanese who saved Mountbatten from so ignoble a role. In spring 1944 they attacked in Arakan and across the Imphal plain into India. The allied capacity to supply troops by air and their new-found determination to stand firm, even when cut off, turned potential disaster into almost total victory. Mountbatten himself played a major role, being personally responsible at a crucial moment for the switch of two divisions by air from Arakan to Imphal and the diversion of the necessary American aircraft from the supply routes to China. Imphal confirmed Mountbatten's faith in the commander of the Fourteenth Army, General W. J. Slim, and led to his final loss of confidence in the commander-in-chief, General Giffard, whom he now dismissed. The battle cost the Japanese 7000 dead; much hard fighting lay ahead, but the Fourteenth Army was on the march that would end at Rangoon.

Mountbatten still hoped to avoid the reconquest of Burma by land. In April 1944 he transferred his headquarters from Delhi to Kandy in Ceylon, reaffirming his faith in a maritime strategy. He himself believed the next move should be a powerful sea and air strike against Rangoon; Churchill still hankered after the more ambitious attack on northern Sumatra; the chiefs of staff felt the British effort should be switched to support the American offensive in the Pacific. In the end shortage of resources dictated the course of events. Mountbatten was able to launch a small seaborne invasion to support the Fourteenth Army's advance, but it was Slim's men who bore the brunt of the fighting and reached Rangoon just before the monsoon broke in April 1945.

Giffard had been replaced as supreme commander by Sir Oliver Leese. Mountbatten's original enthusiasm for Leese did not endure; the latter soon fell out with his supreme commander and proved unpopular with the other commanders-in-chief. A climax came in May 1945 when Leese informed Slim that he was to be relieved from command of the Fourteenth Army because he was tired out and anyway had no experience in maritime operations. Mountbatten's role in this curious transaction remains slightly obscure; Leese definitely went too far, but there may have been some ambiguity about his instructions. In the event Leese's action was disavowed in London and he himself was dismissed and Slim appointed in his place.

The next phase of the campaign—an invasion by sea of the Malay peninsula—should have been the apotheosis of Mountbatten's command. When he went to the Potsdam conference in July 1945, however, he was told of the existence of the atom bomb. He realized at once that this was likely to rob him of his victory and, sure enough, the Japanese surrender reduced operation Zipper to an unopposed landing. This was perhaps just as well; faulty intelligence meant that one of the two landings was made on unsuitable beaches and was quickly bogged down. The invasion would have succeeded but the cost might have been high.

On 12 September 1945 Mountbatten received the formal surrender of the Japanese at Singapore. Not long afterwards he was created a viscount. The honour was deserved. His role had been crucial. 'We did it together' (Ziegler, 295), Slim said to him on his deathbed, and the two men, in many ways so different, had indeed complemented each other admirably and proved the joint architects of victory in south-east Asia.

Mountbatten's work in SEAC did not end with the Japanese surrender; indeed in some ways it grew still more onerous. His command was now extended to include South Vietnam and the Netherlands East Indies: 1.5 million square miles containing 128 million inhabitants, three-quarters of a million armed and potentially truculent Japanese, and 123,000 allied prisoners, many in urgent need of medical attention. Mountbatten had to rescue the prisoners, disarm the Japanese, and restore the various territories to stability so that civil government could resume. This last function proved most difficult, since the Japanese had swept away the old colonial regimes and new nationalist movements had grown up to fill the vacuum. Mountbatten's instincts told him that such movements were inevitable and even desirable. Every effort, he felt, should be made to take account of their justified aspirations. His disposition to sympathize with the radical nationalists sometimes led him into naïvely optimistic assessments of their readiness to compromise with the former colonialist regimes—as proved most notably to be the case with the communist Chinese in Malaya—but the course of subsequent history suggests that he sometimes saw the situation more clearly than the so-called realists who criticized him.

Burma and Malaya

Even before the end of the war Mountbatten had had a foretaste of the problems that lay ahead. Aung San, head of the pro-Japanese Burmese national army, defected with all his troops. Mountbatten was anxious to accept his co-operation, overruled Oliver Leese and his civil affairs staff, and cajoled the somewhat reluctant chiefs of staff into agreeing on military grounds that the former rebels should be rearmed. Inevitably this gave Aung San a stronger position than the traditionalists thought desirable when the time came to form Burma's post-war government. Mountbatten felt that, though left wing and fiercely nationalistic, Aung San was honourable, basically reasonable, and ready to accept the concept of an independent Burma within the British Commonwealth; 'with proper treatment', judged Slim, 'Aung San would have proved a Burmese Smuts' (Ziegler, 319). The governor, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, conceded Aung San was the most popular man in Burma but considered him a dangerous Marxist revolutionary. When Aung San was accused of war crimes committed during the Japanese occupation, Dorman-Smith wished to arrest and try him. Mountbatten forestalled this move and insisted that Aung San was bound to lead Burma one day and that it would be contrary to British interests to try to frustrate him. Aung San's subsequent electoral victory was hailed by Mountbatten as proof that he had backed the only possible horse; to others it meant that violence and intimidation had been not merely condoned but actively encouraged and rewarded. The murder of Aung San the following year meant that the supreme commander's view of his character was never properly tested.

In Malaya the problem was more immediately one of law and order. Confronted by the threat of a politically motivated general strike, the authorities proposed to arrest all the leaders. 'Naturally I ordered them to cancel these orders', wrote Mountbatten, 'as I could not imagine anything more disastrous than to make martyrs of these men' (Ziegler, 326). Reluctantly he agreed that in certain circumstances Chinese trouble-makers might be deported, but rescinded that approval when it was proposed to deport certain detainees who had not had time to profit by his warnings. His critics maintained that sterner action in 1945–6 could have prevented, or at least mitigated, the future troubles in Malaya, but Mountbatten was convinced that the prosperity of Malaya and Singapore depended on the co-operation of Malay and Chinese, and was determined to countenance nothing that might divide the two communities. With hindsight it is possible to see that the largely Chinese guerrillas whom he was disposed to favour were opposed to any sort of foreign influence and would have involved the country in civil war even earlier than actually happened.

In Vietnam and Indonesia Mountbatten's problem was to balance nationalist aspirations against the demands of Britain's allies for support in the recovery of their colonies. He was better disposed to the French than the Dutch, and though he complained when General Douglas Gracey exceeded his instructions and suppressed the Viet Minh—'General Gracey has saved French Indo-China' (Ziegler, 331), Leclerc told him—the reproof was more formal than real. In Indonesia Mountbatten believed that Dutch intransigence was the principal factor preventing a peaceful settlement. Misled by Dutch intelligence, he had no suspicion of the force of nationalist sentiment until Lady Mountbatten returned from her brave foray to rescue allied prisoners of war. His forces could not avoid conflict with the Indonesian nationalists but Mountbatten sought to limit their commitment, with the result that both Dutch and Indonesians believed the British were favouring the other side. He did, however, contrive to keep open the possibility of political settlement; only after the departure of the British forces did full-scale civil war become inevitable.

Mountbatten left south-east Asia in mid-1946 with the reputation of a liberal committed to decolonization. Although he had no thought beyond his return to the navy, with the now substantive rank of rear-admiral, his reputation influenced the Labour government when they were looking for a successor to Viscount Wavell who could resuscitate the faltering negotiations for Indian independence. On 18 December 1946 he was invited to become India's last viceroy. That year he had been created Viscount Mountbatten of Burma.

Viceroy

Mountbatten longed to go to sea again, but this was a challenge no man of ambition and public spirit could reject. His reluctance enabled him to extract favourable terms from the government, and though the plenipotentiary powers to which he was often to refer are not specifically set out in any document, he enjoyed far greater freedom of action than his immediate predecessors. His original insistence that he would go only on the invitation of the Indian leaders was soon abandoned, but it was on his initiative that a terminal date of June 1948 was fixed, by which time the British would definitely have left India.

Mountbatten's directive was that he should strive to implement the recommendations of the cabinet mission of 1946, led by Sir R. Stafford Cripps, which maintained the principle of a united India. By the time he arrived, however, this objective had been tacitly abandoned by every major politician of the subcontinent with the important exception of M. K. Gandhi. The viceroy dutifully tried to persuade all concerned of the benefits of unity, but his efforts foundered on the intransigence of the Muslim leader Mohamed Ali Jinnah. His problem thereafter was to find some formula which would reconcile the desire of the Hindus for a central India, from which a few peripheral and wholly Muslim areas would secede, with Jinnah's aspiration to secure a greater Pakistan, including all of the Punjab and as much as possible of Bengal. In this task he was supported by Wavell's staff from the Indian Civil Service, reinforced by General H. L. Ismay and Sir Eric Miéville. He himself contributed immense energy, charm and persuasiveness, negotiating skills, agility of mind, and endless optimism.

Mountbatten quickly concluded that not only was time not on his side but that the urgency was desperate. The run-down of the British military and civil presence, coupled with swelling inter-communal hatred, was intensely dangerous. 'The situation is everywhere electric, and I get the feeling that the mine may go up at any moment' (Ziegler, 372–3), wrote Ismay to his wife on 25 March 1947, the day after Mountbatten was sworn in as viceroy. This conviction that every moment counted dictated Mountbatten's activities over the next five months. He threw himself into a hectic series of interviews with the various political leaders. With Jawaharlal Nehru he established an immediate and lasting rapport which was to assume great importance in the future. With V. J. Patel, in whom he identified a major power in Indian politics, his initial relationship was less easy, but they soon enjoyed mutual confidence. Gandhi fascinated and delighted him, but he shrewdly concluded that he was likely to be pushed to one side in the forthcoming negotiations. With Jinnah alone did he fail; the full blast of his charm did not thaw or even moderate the chill intractability of the Muslim leader.

Perils of partition

Nevertheless negotiations advanced so rapidly that by 2 May Ismay was taking to London a plan which Mountbatten believed all the principal parties would accept. Only when the British cabinet had already approved the plan did he realize that he had gravely underestimated Nehru's objections to any proposal that left room for the ‘Balkanization’ of India. With extraordinary speed a new draft was produced, which provided for India's membership of the Commonwealth and put less emphasis on the right of the individual components of British India to reject India or Pakistan and opt for independence. After what Mountbatten described as 'the worst 24 hours of my life' (Ziegler, 387), the plan was accepted by all parties on 3 June. He was convinced that any relaxation of the feverish pace would risk destroying the fragile basis of understanding. Independence, he announced, was to be granted in only ten weeks, on 15 August 1947.

Before this date the institutions of British India had to be carved in two. Mountbatten initially hoped to retain a unified army but quickly realized this would be impossible and concentrated instead on ensuring rough justice in the division of the assets. To have given satisfaction to everyone would have been impossible, but at the time few people accused him of partiality. He tackled the problems, wrote Michael Edwardes in a book not generally sympathetic to the last viceroy, 'with a speed and brilliance which it is difficult to believe would have been exercised by any other man' (Edwardes, 178).

The princely states posed a particularly complex problem, since with the end of British rule paramountcy lapsed and there was in theory nothing to stop the princes opting for self-rule. This would have made a geographical nonsense of India and, to a lesser extent, Pakistan, as well as creating a plethora of independent states, many incapable of sustaining such a role. Mountbatten at first attached little importance to the question but, once he was fully aware of it, used every trick to get the rulers to accept accession. Some indeed felt that he was using improper influence on loyal subjects of the crown, but it is hard to see that any other course would in the long run have contributed to their prosperity. Indeed the two states which Mountbatten failed to shepherd into the fold of India or Pakistan—Hyderabad and Kashmir—were those which were subsequently to cause most trouble.

Most provinces, like the princely states, clearly belonged either to India or to Pakistan. In the Punjab and Bengal, however, partition was necessary. This posed horrifying problems, since millions of Hindus and Muslims would find themselves on the wrong side of whatever frontier was established. The Punjab was likely to prove most troublesome, because 14 per cent of its population consisted of Sikhs, who were warlike, fanatically anti-Muslim, and determined that their homelands should remain inviolate. Partition was not Mountbatten's direct responsibility, since Sir Cyril Radcliffe was appointed to divide the two provinces.

Mountbatten always maintained that he had scrupulously held aloof from the process, and Radcliffe himself denied that he had been put under any pressure by the viceroy. Evidence which has subsequently come to light, however, suggests that Mountbatten was further involved than he cared to admit and that he urged on Radcliffe frontier adjustments in favour of the Indians in the Punjab which were to be counterbalanced by concessions to the Muslims in Bengal. The effect, in the Punjab, was that certain important headwaters were awarded to India rather than Pakistan; this made economic and social sense, but the importance of the change was not conceivably great enough to outweigh the damage that would have been done if it had become generally known that the viceroy was interfering in this way. There is no reason to accept, however, the belief still held by many Pakistanis that Mountbatten secured the switch from Pakistan to India of territory in Gurdaspur which gave India easy land access to Kashmir and thus facilitated that state's eventual accession to India. On the contrary, at the time of partition Mountbatten was actively trying to persuade the maharaja of Kashmir that he should accede to Pakistan. At one point he had even managed to convince Nehru that this would be a tolerable conclusion.

Mountbatten had hoped that independence day would see him installed as governor-general of both new dominions, able to act, in Churchill's phrase, as 'moderator' during their inevitable differences. Nehru was ready for such a transmogrification but Jinnah, after some months of apparent indecision, concluded that he himself must be Pakistan's first head of state. Mountbatten was uncertain whether the last viceroy of a united India should now reappear as governor-general of a part of it, but the Indian government pressed him to accept, and in London both Attlee and George VI felt the appointment was desirable. With some misgivings, Mountbatten gave way. Independence day in both Pakistan and India was a triumph, tumultuous millions applauding his progress and demonstrating that, for the moment at least, he enjoyed a place in the pantheon with their national leaders. 'No other living man could have got the thing through', wrote Lord Killearn to Ismay; 'it has been a job supremely well done' (Ziegler, 427).

Communal strife

The euphoria quickly faded. Although Bengal remained calm, thanks largely to Gandhi's personal intervention, the Punjab exploded. Vast movements of population across the new frontier exacerbated the already inflamed communal hatred, and massacres on an appalling scale developed. The largely British-officered boundary force was taxed far beyond its powers, and Delhi itself was engulfed in the violence. Mountbatten was called back from holiday to help master the emergency, and brought desperately needed energy and organizational skills to the despondent government. 'I've never been through such a time in my life', he wrote on 28 September, 'The War, the Viceroyalty were jokes, for we have been dealing with life and death in our own city' (Ziegler, 436). Gradually order was restored, and by November 1947 Mountbatten felt the situation was stable enough to permit him to attend the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and his nephew Philip Mountbatten in London. He was created Earl Mountbatten of Burma, with special remainder to his daughter Patricia.

Estimates vary widely, but the best-documented assessments agree that at least 250,000 people lost their lives in the communal riots. Those who criticize Mountbatten's viceroyalty do so most often on the grounds that these massacres could have been averted, or at least mitigated, if partition had not been hurried through. Mountbatten's champions maintain that delay would only have made things worse and allowed the disorders to spread further. It is impossible to state conclusively what might have happened if independence had been postponed by a few months, or even years, but it is noteworthy that the closer people were to the problem, the more they supported Mountbatten's policy. Almost every senior member of the British administration in India and of the Indian government has recorded his conviction that security was deteriorating so fast, and the maintenance of non-communal forces of law and order proving so difficult, that a far greater catastrophe would have ensued if there had been further delay.

Mountbatten as governor-general was a servant of the Indian government and, as Ismay put it, 'it is only natural that they … should regard themselves as having proprietary rights over you' (Ziegler, 465–6). Mountbatten accepted this role and fought doughtily for India's interests. He did not wholly abandon impartiality, however. When in January 1948 the Indian government withheld from Pakistan the 55 million crores of rupees owing after the division of assets, the governor-general argued that such conduct was dishonourable as well as unwise. He recruited Gandhi as his ally, and together they forced a change of policy on the reluctant Indian ministers. It was one of Gandhi's final contributions to Indian history. On 30 January he was assassinated by a Hindu extremist. Mountbatten mourned him sincerely. 'What a remarkable old boy he was', he wrote to a friend, 'I think history will link him with Buddha and Mahomet' (Ziegler, 471).

Mountbatten's stand over the division of assets did the governor-general little good in Pakistan, where he was believed to be an inveterate enemy. When, in October 1947, Pathan tribesmen invaded the Vale of Kashmir, Mountbatten approved and helped to organize military intervention by India. He insisted, however, that the state must first accede and that, as soon as possible, a plebiscite should establish the wishes of the Kashmiri people. When war between India and Pakistan seemed imminent he was instrumental in persuading Nehru that the matter should be referred to the United Nations.

The other problem that bedevilled Mountbatten was that of Hyderabad. He constituted himself, in effect, chief negotiator for the Indian government and almost brought off a deal that would have secured reasonably generous terms for the nizam. Muslim extremists in Hyderabad, however, defeated his efforts, and the dispute grumbled on. Mountbatten protested when he found contingency plans existed for the invasion of Hyderabad, and his presence was undoubtedly a main factor in inhibiting the Indian take-over that quickly followed his departure.

On 21 June 1948 the Mountbattens left India. In his final address, Nehru referred to the vast crowds that had attended their last appearances and wondered 'how it was that an Englishman and Englishwoman could become so popular in India during this brief period' (Ziegler, 478–9). Even his harshest critics could not deny that Mountbatten had won the love and trust of the people and got the relationship between India and her former ruler off to a far better start than had seemed possible fifteen months before.

Return to the navy

At last Mountbatten was free to return to sea. Reverting to his substantive rank of rear-admiral he took command of the 1st cruiser squadron in the Mediterranean. To assume this relatively lowly position after the splendours of supreme command and viceroyalty could not have been easy, but with goodwill all round it was achieved successfully. He was 'as great a subordinate as he is a leader' (Ziegler, 495), reported the commander-in-chief, Admiral Sir Arthur Power. He brought his squadron up to a high level of efficiency, though he did not conceal the fact that he felt obsolescent material and undermanning diminished its real effectiveness. After his previous jobs this command was something of a holiday, and he revelled in the opportunities to play his beloved polo and take up skin diving. In Malta he stuck to his inconspicuous role, but abroad he was fêted by the rulers of the countries his squadron visited. 'I suppose I oughtn't to get a kick out of being treated like a Viceroy', he confessed after one particularly successful visit, 'but I'd have been less than human if I hadn't been affected by the treatment I received at Trieste' (Ziegler, 490). He was never less, nor more, than human.

Mountbatten was promoted vice-admiral in 1949 and in June 1950 returned to the Admiralty as fourth sea lord. He was at first disappointed, since he had set his heart on being second sea lord, responsible for personnel, and found himself instead concerned with supplies and transport. In fact the post proved excellent for his career. He flung himself into the work with characteristic zeal, cleared up many anomalies and outdated practices, and acquired a range of information which was to stand him in good stead when he became first sea lord. On the whole he confined himself to the duties of his department, but when the Persians nationalized Anglo-Iranian Oil in 1951 he could not resist making his opinions known. He felt that it was futile to oppose strong nationalist movements of this kind and that Britain would do better to work with them. He converted the first lord to his point of view but conspicuously failed to impress the bellicose foreign secretary, Herbert Morrison.

The next step was command of a major fleet; in June 1952 he was appointed to the Mediterranean and the following year he was promoted admiral. St Vincent remarked that naval command in the Mediterranean 'required an officer of splendour' (Ziegler, 508), and this Mountbatten certainly provided. He was not a great operational commander like Andrew Cunningham, but he knew his ships and personnel, maintained the fleet at the highest level of peacetime efficiency, and was immensely popular with the men. When ‘Cassandra’ of the Daily Mirror arrived to report on Mountbatten's position, he kept aloof for four days, then came to the flagship with the news that the commander-in-chief was 'O.K. with the sailors' (Ziegler, 512). But it was on the representational side that Mountbatten excelled. He loved showing the flag and, given half a chance, would act as honorary ambassador into the bargain. Sometimes he overdid it, and in September 1952 the first lord, at the instance of the prime minister, wrote to urge him to take the greatest care to keep out of political discussions.

Mountbatten's diplomatic as well as administrative skills were taxed when in January 1953 he was appointed supreme allied commander of a new NATO Mediterranean command (SACMED). Under him were the Mediterranean fleets of Britain, France, Italy, Greece, and Turkey, but not the most powerful single unit in the area, the American Sixth Fleet. He was required to set up an integrated international naval and air headquarters in Malta and managed this formidable organizational task with great efficiency. The smoothing over of national susceptibilities and the reconciliation of his British with his NATO role proved taxing, but his worst difficulty lay with the other NATO headquarters in the Mediterranean, CINCSOUTH, at Naples under the American admiral R. B. Carney. There were real problems of demarcation but, as had happened with Somerville in south-east Asia, these were made far worse by a clash of personalities. When Carney was replaced in the autumn of 1953, the differences melted away and the two commands began to co-operate.

First sea lord

In October 1954, when he became first sea lord, Mountbatten achieved what he had always held to be his ultimate ambition. It did not come easily. A formidable body of senior naval opinion distrusted him and was at first opposed to his appointment, and it was not until the conviction hardened that the navy was losing the Whitehall battle against the other services that opinion rallied behind him. 'The Navy wants badly a man and a leader', wrote Andrew Cunningham, who had formerly been Mountbatten's opponent. 'You have the ability and the drive and it is you that the Navy wants' (Ziegler, 523). Churchill, still unreconciled to Mountbatten's role in India, held out longer, but in the end he too gave way.

Since the war the navy had become the Cinderella of the fighting services, and morale was low. Under Mountbatten's leadership the Admiralty's voice in Whitehall became louder and more articulate. By setting up the Way Ahead committee he initiated an overdue rethinking of the shore establishments, which were absorbing an undue proportion of the navy's resources. He scrapped plans for the construction of a heavy missile-carrying cruiser and instead concentrated on destroyers carrying the Sea Slug missile: 'Once we can obtain Government agreement to the fact that we are the mobile large scale rocket carriers of the future then everything else will fall into place' (Ziegler, 531). The Reserve Fleet was cut severely and expenditure diverted from the already excellent communications system to relatively underdeveloped fields such as radar. Probably his most important single contribution, however, was to establish an excellent relationship with the notoriously prickly Admiral Rickover, which was to lead to Britain's acquiring US technology for its nuclear submarines and, eventually, to the adoption of the Polaris missile as the core of its nuclear deterrent.

In July 1956 Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal. Mountbatten was asked what military steps could be taken to restore the situation. He said that the Mediterranean Fleet with the Royal Marine commandos aboard could be at Port Said within three days and take the port and its hinterland. Eden rejected the proposal since he wished to reoccupy the whole canal zone, and it is unlikely anyway that the other chiefs of staff would have approved a plan that might have left lightly armed British forces exposed to tank attack and with inadequate air cover. As plans for full-scale invasion were prepared, Mountbatten became more and more uneasy about the contemplated action. To the chiefs of staff he consistently said that political implications should be considered and more thought given to the long-term future of the Middle East. His views were reflected in the chiefs' recommendations to the government, a point that caused considerable irritation to Anthony Eden, who insisted that politics should be left to the politicians. In August Mountbatten drafted a letter of resignation to the prime minister but, without too much difficulty, was dissuaded from sending it by the first lord, Viscount Cilcennin. He was, however, instrumental in substituting the invasion plan of General Sir Charles Keightley for that previously approved by the cabinet, a move that saved the lives of many hundreds of civilians. On 2 November 1956, when the invasion fleet had already sailed, Mountbatten made a written appeal to Eden to accept the United Nations resolution and 'turn back the assault convoy before it is too late' (Ziegler, 545). His appeal was ignored. Mountbatten again offered his resignation to the first lord and again was told that it was his duty to stay on. He was promoted admiral of the fleet in October 1956.

With Harold Macmillan succeeding Eden as prime minister in January 1957, Duncan Sandys was appointed minister of defence with a mandate to rationalize the armed services and impose sweeping economies. There were many embittered battles before Sandys's first defence white paper appeared in the summer of 1957. The thirteenth and final draft contained the ominous words: 'the role of the Navy in Global War is somewhat uncertain' (Ziegler, 552). In the event, however, the navy suffered relatively lightly, losing only one-sixth of its personnel over the next five years, as opposed to the army's 45 per cent and the air force's 35 per cent. The role of the navy east of Suez was enshrined as an accepted dogma of defence policy.

Chief of defence staff

In July 1959 Mountbatten took over as chief of defence staff (CDS). He was the second incumbent, Sir William Dickson having been appointed in 1958, with Mountbatten's support but against the fierce opposition of Field Marshal Sir Gerald Templer. Dickson's role was little more than that of permanent chairman of the chiefs of staff committee, but Sandys tried to increase the CDS's powers. He was defeated, and the defence white paper of 1958 made only modest changes to the existing system. Mountbatten made the principal objective of his time as CDS the integration of the three services, not to the extent achieved by the Canadians of one homogenized fighting force, but abolishing the independent ministries and setting up a common list for all senior officers. During his first two years, however, he had to remain content with the creation of a director of defence plans to unify the work of the three planning departments and the acceptance of the principle of unified command in the Far and Middle East. Then, at the end of 1962, Macmillan agreed that another attempt should be made to impose unification on the reluctant services. 'Pray take no notice of any obstructions', he told the minister of defence, 'You should approach this … with dashing, slashing methods. Anyone who raises any objection can go' (Macmillan, 418).

At Mountbatten's suggestion Lord Ismay and Sir E. Ian Jacob were asked to report. While not accepting all Mountbatten's recommendations—which involved a sweeping increase in the powers of the CDS—their report went a long way towards realizing the concept of a unified Ministry of Defence. The reforms, which were finally promulgated in 1964, acknowledged the supreme authority of the secretary of state for defence and strengthened the central role of the CDS. To Mountbatten this was an important first step, but only a step. He believed that so long as separate departments survived, with differing interests and loyalties, it would be impossible to use limited resources to the best advantage. Admiralty, War Office, Air Ministry—not to mention Ministry of Aviation—should be abolished. Ministers should be responsible, not for the navy or the air force, but for communications or supplies. 'We cannot, in my opinion, afford to stand pat', he wrote to Harold Wilson when the latter became prime minister in October 1964, 'and must move on to, or at least towards the ultimate aim of a functional, closely knit, smoothly working machine' (Ziegler, 629). 'Functionalization' was the objective which he repeatedly pressed on the new minister of defence, Denis Healey. Healey was well disposed in principle, but felt that other reforms enjoyed higher priority. Although Mountbatten appealed to Wilson he obtained little satisfaction, and the machinery which he left behind him at his retirement was in his eyes only an unsatisfactory partial solution.

Even for this Mountbatten paid a high price in popularity. His ideas were for the most part repugnant to the chiefs of staff, who suspected him of seeking personal aggrandizement and doubted the propriety of his methods. Relations tended to be worst with the chiefs of air staff. The latter believed that Mountbatten, though ostensibly above inter-service rivalries, in fact remained devoted to the interests of the navy. It is hard entirely to slough off a lifetime's loyalties, but Mountbatten tried to be impartial. He did not always succeed. On the long-drawn-out battle over the merits of aircraft-carriers and island bases, he espoused the former. When he urged the first sea lord to work out some compromise which would accommodate both points of view, Sir Caspar John retorted that only a month before Mountbatten had advised him: 'Don't compromise—fight him to the death!' (Broadlands MSS, J172, Sir C. John to Mountbatten, 16 Jan 1963). Similarly, in the conflict between the TSR 2, sponsored by the air force, and the navy's Buccaneer, Mountbatten believed strongly that the former, though potentially the better plane, was too expensive to be practicable and would take too long to develop. He lobbied the minister of defence and urged his right-hand man, Solly Zuckerman, to argue the case against the TSR 2—'You know why I can't help you in Public. It is not moral cowardice but fear that my usefulness as Chairman would be seriously impaired' (Ziegler, 587).

The question of the British nuclear deterrent also involved inter-service rivalries. Mountbatten believed that an independent deterrent was essential, arguing to Harold Wilson that it would 'dispel in Russian minds the thought that they will escape scot-free if by any chance the Americans decide to hold back release of a strategic nuclear response to an attack' (Ziegler, 627). He was instrumental in persuading the incoming Labour government not to adopt unilateral nuclear disarmament. In this he had the support of the three chiefs of staff. But there was controversy over what weapon best suited Britain's needs. From long before he became CDS, Mountbatten had privately preferred the submarine-launched Polaris missile to any of the airborne missiles favoured by the air force. Though not himself present at the meeting at Nassau between Macmillan and President John F. Kennedy, at which Polaris was offered and accepted in exchange for the cancelled Skybolt missile, he had already urged this solution and had made plans accordingly.

Although he defended the nuclear deterrent, Mountbatten was wholly opposed to the accumulation of unnecessary stockpiles or the development of new weapons designed to kill more effectively people who would be dead anyway if the existing armouries were employed. At NATO in July 1963 he pleaded that 'it was madness to hold further tests when all men of goodwill were about to try and bring about test-banning' (Broadlands MSS, interviews with Robin Bousfield, transcripts of tapes, vol. 1). He conceded that tactical nuclear weapons added to the efficacy of the deterrent, but argued that their numbers should be limited and their use subject to stringent control. To use any nuclear weapon, however small or 'clean', would, he insisted, lead to general nuclear war. He opposed the 'mixed manned multilateral force' not just as being military nonsense, but because there were more than enough strategic nuclear weapons already. What were needed, he told the NATO commanders in his valedictory address, were more 'highly mobile, well-equipped, self-supporting and balanced “Fire Brigade” forces, with first-class communications, able to converge quickly on the enemy force' (Broadlands MSS, J284, annex A to COS/1918/21/6/65).

Mountbatten's original tenure of office as CDS had been for three years. Macmillan pressed him to lengthen this by a further two years to July 1964. Mountbatten was initially reluctant but changed his mind after the death of his wife in 1960. He later agreed to a further extension, to July 1965, in order to see through the first phase of defence reorganization. Wilson would have happily sanctioned yet another year, but Healey established that there would be considerable resentment at such a move on the part of the other service leaders and felt anyway that he would never be fully master of the Ministry of Defence while this potent relic from the past remained in office. Whether Mountbatten would have stayed on if pressed to do so is in any case doubtful; he was tired and stale, and had a multiplicity of interests to pursue outside.

Mountbatten's last few months as CDS were in fact spent partly abroad, leading a mission on Commonwealth immigration. The main purpose of this exercise was to explain British policy and persuade Commonwealth governments to control illegal immigration at source. The mission was a success; indeed Mountbatten found that he was largely preaching to the converted, since only in Jamaica did the policy he was expounding meet with serious opposition. He presented the mission's report on 13 June 1965 and the following month took his formal farewell of the Ministry of Defence.

Final years

Retirement did not mean inactivity; indeed Mountbatten was still officially enjoying his retirement leave when the prime minister invited him to go to Rhodesia as governor to forestall a declaration of independence by the white settler population. Mountbatten had little hesitation in refusing: 'Nothing could be worse for the cause you have at heart than to think that a tired out widower of 65 could recapture the youth, strength and enthusiasm of twenty years ago' (Ziegler, 648). However, he accepted a later suggestion that he should fly briefly to Rhodesia in November 1965 to invest the governor, Sir Humphrey Gibbs, with a decoration on behalf of the queen and generally to offer moral support. At the last minute the project was deferred and never revived.

The following year the home secretary asked Mountbatten to undertake an inquiry into prison security, in view of a number of recent sensational escapes. Mountbatten agreed, provided it could be a one-man report prepared with the help of three assessors. The report was complete within two months and most of the recommendations were carried out. The two most important, however—the appointment of an inspector-general responsible to the home secretary to head the prison service, and the building of a separate maximum security gaol for prisoners whose escape would be particularly damaging—were never implemented. For the latter proposal Mountbatten was much criticized by liberal reformers who felt the step a retrograde one; this Mountbatten contested, arguing that, isolated within a completely secure outer perimeter, the dangerous criminal could be allowed more freedom than would otherwise be the case.

Mountbatten was associated with 179 organizations, ranging alphabetically from the Admiralty Dramatic Society to the Zoological Society. In some of these his role was formal, in many more it was not. In time and effort the United World Colleges, a network of international schools modelled on the Gordonstoun of Kurt Hahn, received the largest share. Mountbatten worked indefatigably to whip up support and raise funds for the schools, lobbying the leaders of every country he visited. The electronics industry, also, engaged his attention, and he was an active first chairman of the National Electronics Research Council. In 1965 he was installed as governor of the Isle of Wight and conscientiously visited the island seven or eight times a year; in 1974 he became the first lord lieutenant when the island was raised to the status of a shire. A role which gave him still greater pleasure was that of colonel of the Life Guards, to which he was also appointed in 1965. He took his duties at trooping the colour very seriously and for weeks beforehand would ride around the Hampshire lanes near Broadlands in hacking jacket and Life Guards helmet.

Mountbatten's personal life was equally crowded. The years 1966 and 1967 were much occupied with the filming of the thirteen-part television series The Life and Times of Lord Mountbatten, every detail of which absorbed him and whose sale he promoted energetically all over the world. He devoted much time to running the family estates and putting his massive archive in order, and involved himself enthusiastically in the opening of Broadlands to the public, which took place in 1978. He never lost his interest in naval affairs or in high strategy. One of his last major speeches was delivered at Strasbourg in May 1979, when he pleaded eloquently for arms control:

As a military man who has given half a century of active service I say in all sincerity that the nuclear arms race has no military purpose. Wars cannot be fought with nuclear weapons. Their existence only adds to our perils because of the illusions which they have generated.

Ziegler, 695

Some of Mountbatten's happiest hours were spent on tour with the royal family in their official yacht Britannia. He attached enormous importance to his royal connections and, though his influence was not so significant as he chose to imagine, his voice was often heard and sometimes heeded in Buckingham Palace—too often heard in the view of certain courtiers, who thought him a dangerous busybody. On the whole he spoke for modernization and the pruning of ancient ceremonies; he loved the rituals of state but was realistic enough to see the dangers of treating them as immutable and sacrosanct.

Mountbatten derived particular pleasure from his friendship with the prince of Wales, who treated him as ‘honorary grandfather’ and attached great value to his counsel. Mountbatten always urged the prince to sow his wild oats and then to marry and stick to a pure girl of good family; the advice was admirable in principle but proved impossible to apply in practice. It is conceivable that, if Mountbatten had lived and retained sufficient vigour, he might have played a father confessor role in the lives of both the prince and princess of Wales and helped to make their marriage less disastrous.

When Princess Anne married, the certificate gave as her surname Mountbatten-Windsor. This was the culmination of a long battle Mountbatten had waged to ensure that his family name, adopted by Prince Philip, should be preserved among his nephew's descendants. He took an intense interest in all the royal houses of Europe and was a source of advice on every subject. Harold Wilson once called him 'the shop-steward of royalty' (private information), and Mountbatten rejoiced in the description.

Death and significance

Every summer Mountbatten enjoyed a family holiday at his Irish home in co. Sligo, Classiebawn Castle. Over the years the size of his police escort increased, but the Irish authorities were insistent that the cancellation of his holiday would be a victory for the Irish Republican Army. On 27 August 1979 a family party went out in a fishing boat, to collect lobster pots set the previous day. A bomb exploded when the boat was half a mile from Mullaghmoor harbour. Mountbatten was killed instantly, as were his grandson Nicholas and a local Irish boy. His daughter's mother-in-law, Doreen, Lady Brabourne, died shortly afterwards; his daughter Patricia and son-in-law Lord Brabourne were badly injured but later recovered. Mountbatten's funeral took place in Westminster Abbey and he was buried in Romsey Abbey on 5 September. He had begun his preparations for the ceremony more than ten years before and was responsible for planning every detail, down to the lunch to be eaten by the mourners on the train from Waterloo to Romsey.

Mountbatten was a giant of a man, and his weaknesses were appropriately gigantic. His vanity was monstrous, his ambition unbridled. The truth, in his hands, was swiftly converted from what it was to what it should have been. But such frailties were far outweighed by his qualities. His energy was prodigious, as was his moral and physical courage. He was endlessly resilient in the face of disaster. No intellectual, he possessed a powerfully analytical intelligence; he could rapidly master a complex brief, spot the essential, and argue it persuasively. His flexibility of mind was extraordinary, as was his tolerance—he accepted all comers for what they were, not measured against some scale of predetermined values. He had style and panache and commanded the loyal devotion of those who served him. To his opponents in Whitehall he was ‘tricky Dickie’, devious and unscrupulous. To his family and close friends he was a man of wisdom and generosity. He adored his two daughters, Patricia and Pamela, and his ten grandchildren. However pressing his preoccupations he would make time to comfort, encourage, or advise them. Almost always the advice was good.

Among Mountbatten's honours were MVO (1920), KCVO (1922), GCVO (1937), DSO (1941), CB (1943), KCB (1945), KG (1946), privy councillor (1947), GCSI (1947), GCIE (1947), GCB (1955), OM (1965), and FRS (1966). He received an honorary DCL from Oxford (1946) and honorary LLDs from Cambridge (1946), Leeds (1950), Edinburgh (1954), Southampton (1955), London (1960), and Sussex (1963). He was honorary DSc of Delhi and Patna (1948). On Mountbatten's death the title passed to his elder daughter, Patricia Edwina Victoria Knatchbull (b. 1924), who became Countess Mountbatten of Burma.

- Philip Ziegler DNB.

Spear, (Augustus John) Ruskin (1911–1990), artist and teacher of art, was born on 30 June 1911 in Hammersmith, London, the only son and youngest of five children of Augustus Spear, coach builder and coach painter, and his wife, (Matilda) Jane Lemon, cook. He acquired his unusual and appropriate forenames by being named Augustus after his father, John after his maternal grandfather, and Ruskin after a member of the artistically inclined family with whom his mother was in service at the time of his birth. Disabled by polio at an early age, Spear attended the Brook Green School, Hammersmith, for afflicted children, where his artistic talent was recognized. He went on to study at the Hammersmith School of Art on a scholarship, aged about fifteen, and then at the Royal College of Art in London (1930–34), on another scholarship, under Sir William Rothenstein.

Spear subsidized his own work by teaching, stating that he 'tried to believe money unimportant', and he noted wryly: 'first teaching appointment Croydon School of Art. Fee for 2½ hours, 16 shillings plus train fare. The Principal, interested in palmistry, read my hand, deciding it was promising, offered me four days per week'. He taught at Croydon, Sidcup, Bromley, St Martin's, Central, and Hammersmith schools of art, and—notably—as a visiting teacher in the painting school at the Royal College of Art (1952–77). He was also a gifted musician, and added to his income by playing jazz piano.

Throughout his life Spear regarded himself as 'a working-class cockney', while pursuing an extensive career as one of the liveliest members of the art world, loved by the public, fellow artists, and students, but only occasionally by the critics, by whom he was not taken seriously. He was a robust character, direct, colourful, pipe-smoking, and bearded. Known as a man with a prodigious thirst, he frequented his local pubs in Hammersmith and Chiswick, where his fellow drinkers formed a substantial proportion of his subject matter. He summed up his life view thus: 'Painting, breathing, drinking, ars longa, vita brevis'. His polio caused a permanent limp and prevented active service in the Second World War. He did, however, contribute noteworthy paintings of working life on the home front, commissioned and purchased by the War Artists' Advisory Committee.

Spear became an associate of the Royal Academy in 1944 and Royal Academician in 1954. This enabled him as of right to contribute to the academy's summer exhibitions, where he had first exhibited in 1932. His facility with paint, and his fascination with low life and high life, and the foibles of both, often made his contributions newsworthy. Pub characters, members of the royal family, and politicians were his favourite subjects for academy presentation, with the portraits of public figures often based on newspaper photographs. He was a gentle satirist, exaggerating what was there rather than turning to stereotypes. He also portrayed ordinary life with vivid sympathy; a painting of a mother potting a baby caused the president of the Royal Academy, Sir Alfred Munnings, such displeasure in 1944 that it was not shown. In 1942 Spear was elected to the London Group, and was its president in 1949–50.

Spear had a thriving portrait practice among prominent figures. His subjects, which he proudly listed in his Who's Who entry, included lords Butler, Adrian, Olivier as Macbeth (painted from life), and Ramsey of Canterbury, Sir John Betjeman in a rowing boat, and lords Goodman and Howe of Aberavon. He was a portrayer of the human comedy with a light touch, in spite of often using a dark palette. He never had regular showings or a contract with a commercial gallery. He did occasionally exhibit abroad, but the only substantial exhibition of his work ever held in Britain (or anywhere) was the retrospective in the Diploma Galleries in the Royal Academy in 1980. The National Portrait Gallery has several of his portraits.

In spite of the relatively conventional, if exuberant, nature of his own work Spear promoted what he called the 'modern chaps', and was instrumental in turning the academy away from its unhealthy nostalgia; he was assisted by his outstanding success as a teacher during a golden age at the Royal College (Ron Kitaj, Frank Auerbach, David Hockney, and Peter Blake were his students). 'We did a lot of teaching. The atmosphere tingled with the excitement of being free.' Spear himself produced portraits endowed with sympathy; he was also a fascinating reporter, but his portrayals often appeared skin-deep rather than profound, and his talent was ‘made in England’ and not for travel. He was appointed CBE in 1979.

In 1935 Spear married (Hilda) Mary, artist and only child of William Henry Freer Hill, civil engineer, and Hilda Anne Grose; they had a son. The existence of his long-lasting liaison with Claire Stafford, an artist's model whom he met in 1956 when she was sixteen, was posthumously publicly revealed in 1993. They had a daughter, Rachel Spear-Stafford (b. 1957). Spear died in Hammersmith on 17 January 1990. A memorial service was held at St James's, Piccadilly, London, on 14 March 1990.

DNB. Oxford.