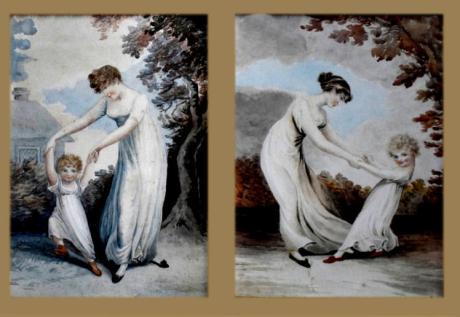

a pair of watercolours (2) 28 x 19 cm each

It’s a truth universally acknowledged that after a bride and groom consummate the marriage the pitter patter of little feet will surely follow (and follow and follow and follow). Such was the case during Jane Austen’s day. Her mother bore eight children and luckily survived her ordeals. The wives of Jane’s brothers Edward and Frank did not, both dying in childbirth with their eleventh child. That these two women were able to survive so many pregnancies was a miracle in itself, given that the chance of a woman dying in childbirth at the time was 20%.

Deborah Kaplan writes in Jane Austen Among Women:

“On the birth of his fourteenth child in 1817, Thomas Papillon received this advice within a letter of congratulations from his wife’s uncle, Sir Richard Hardinge: It is now recommended to you to deprive Yourself of the Power of Further Propagation. You have both done Well and Sufficiently.”

Abstinence was one method of birth control, as Sir Richard recommended. Breast feeding was another. If a mother breasfed her child for 3-4 years, the pregnancies would be naturally spaced inbetween periods of amenorrhea (the absence of menstruation). While breastfeeding regained some popularity during the Georgian and Regency eras, women did not feed their babies long enough to supress menstruation for very long and often handed them over to a wet nurse. Cassandra Austen farmed her children to a nurse in a nearby village after six to eight months, guaranteeing that her lactation would soon cease and that she would soon be fertile again. The common belief that having intercourse during lactation would in some way harm the mother and child did offer some added protection from pregnancy, but large families were still common.

Once children were born and the family was large, it was not unusual to farm out a few children, some to work in their childhood, as Charles Dickens did, and other to live with relatives, as was the case with Fanny Price, who lived with her aunt’s family in Mansfield Park and Edward Austen Knight, who was adopted by a rich, childless couple.

It has been said that families had many children during the 18th and 19th centuries because of the high rate of infant mortality and the need for many helping hands on the farm. But as society became industrialized, large families became a hindrance. With many mouths to feed and limited resources (except in the case of the rich), it is no wonder that couples since time immemorial have searched for ways to limit the number of their offspring. Update: As Nancy Mayer rightly pointed out in her comment, most women during the Georgian and Regency eras thought it their duty to bear their husbands children and oversee the family household. The matter of family planning might well have been influenced by women of a certain class who could not allow pregnancies to interfere with the rhythm of the work cycle, single women who were desperate to seek ways to end their pregnancies before their condition became obvious, and in houses of ill repute, where condoms would offer some protection against disease. Mistresses and prostitutes would find pregnancies to be more of a hindrance than help in their work. I have often wondered, for example, how Emma Hamilton managed to have so few children and yet enjoy the charms of so many men.

In the eighteenth century, the prevailing belief about children was that they should be treated (and be expected to behave) as miniature adults. The advice we hear today, to let kids be kids? Not something you would have heard in the early Georgian-era of powdered wigs and telling French peasants to eat cake. But round and about the turn of the nineteenth century, there was a tremendous change in not only how children were brought into the world, but how they were raised.

Obstetricians began to take the place of midwives, and women were encouraged to “lie in” for at least a month after giving birth, taking on help from neighbors and family. Many households still sent their young children off to be cared for by wet nurses from about the age of three months (poorer households would most likely not have this option) presumably to give the mother freedom to re-enter society and also to bring about the ability to have more children quickly. (Jane Austen, for instance, was sent to live with another family from the age of three months to two years. As dire as this sounds, she was visited by one or both of her parents every day. Though this practice was looked down on by the generations immediately followed.)

The tight, constraining swaddling of an infant that had been the norm in the eighteenth century was pushed aside in an effort to give babies more freedom of movement. Swaddling had also been used in an effort to keep babies calm and quiet, as if the crying of a child was a bad thing. In the nineteenth century, adults began to understand that crying was a normal part of infancy and childhood, often a result of the baby and child still learning how to express themselves.

Play and games were encouraged as being essential towards a child’s development, and children’s clothing reflected these changing attitudes. While babies were kept in long gowns to keep them warm, as soon as they reached the age of crawling and walking, they were placed in “short clothes” to give their chubby little legs room to maneuver. Pudding caps were used as well, a slightly padded helmet, of sorts, to help prevent the bumps and bruises that came with learning to walk and run and jump. (And just when you thought overprotective parenting was a modern invention…)

Children were also drawn tighter into the bosom of the family, and many households all ate their meals together rather than keeping the children separate with a nursemaid round the clock. The belief was that they would better learn to socialize and grow into better adults by seeing the behavior of their elders and to “practice” with them. But it had the added benefit of keeping the family together and letting the parents and children play a larger part in each other’s lives.

By the age of eight is when things would begin to change in the child’s life. If you were a boy, your education went into overdrive. Being sent off to school, the hiring of a tutor, or being sent to learn from the local parson were all popular options. Girls, on the other hand, were more likely to be kept at home for their education (especially as a girl’s education consisted of things like needlework, painting, music, and less history, science, and languages than their brothers). A governess would often be added to the household staff (though we all remember Lady Catherine De Bourgh’s horror at discovering that all five Bennet daughters were raised without the aid of a governess).

As the nineteenth century moved forward, the role of motherhood and the importance of children being children only progressed further. A short while after the Regency period, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert arrived, two people who both reportedly doted on their children (all nine of them!) and all while running an empire. Now, nearly two centuries later, it is remarkable how many things have changed, and yet how with the upswing in popularity of cloth diapers and midwives and ensuring that kids have ample time to play, just how many things have remained the same.

Edridge, Henry (1768–1821), portrait painter and landscape draughtsman, was born at Paddington, Middlesex, in August 1768, and baptized in St James's, Paddington, on 3 October 1768, the son of Henry Edridge, a tradesman in St James's and his wife, Sarah, née Brett. He was educated by his mother and at a school in Acton, before being apprenticed at fifteen to the mezzotint engraver William Pether. Edridge acquired an eye for detail in this meticulous work; he was also given permission to study his master's other work as a miniaturist. He attended the Royal Academy Schools from 1784 and his copies after the works of Reynolds were much admired by Sir Joshua. He married Ann in 1789 and at the same time set up in London on his own at 14 Church Street, Soho, and then at 5 Old Compton Street. He was in business at 10 Dufour's Place from 1790 to 1799, when his reputation was being established, and also worked from a cottage he had purchased at Hanwell, Middlesex. In 1789 Edridge had become acquainted with the landscape watercolourist Thomas Hearne, and went sketching with him, adopting a little of his style and technique. Through Hearne he met Dr Thomas Monro and after 1794 attended Monro's unofficial drawing school at Adelphi Terrace in company with J. M. W. Turner and Thomas Girtin. But Edridge was already becoming well known for a style of portraiture that combined the delicacy of miniature painting with breadth of draughtsmanship and also included landscape. His earliest (anonymous) biographer stated:

It was only of late years that he made those elaborately high-finished pictures on paper, uniting the depth and richness of oil paintings with the freedom and freshness of water-colours, and of which there is perhaps scarcely a nobleman's family in England without some specimens.

Georgian Era

It was not strictly true that these watercolour full-lengths were late works: he had been engaged on them since 1790 but perfected them from 1805 to 1810, when he exhibited almost 200 at the Royal Academy. Edridge drew his subject in soft lead pencil, applying watercolour with a miniaturist's technique of stippling, principally to the face and hands, but using some washes or body colour to enrich the drapery. His meticulous pencil lines, occasionally strengthened by pen, give his figures a posed appearance, but the accuracy of dress and detail is remarkable. An accomplished landscape draughtsman, Edridge used trees, especially silver birches, to enliven the background, and details of a house or a terrace to set the figure in a topographical context. The outline and the drapery of his sitters exactly suited the neo-classical mood of the time.

Joseph Farington gave some indication of Edridge's popularity when he noted in his diary on 30 December 1805 that he was invited to Windsor in 1805, 'where he is employed in making a set of drawings of the Princesses to be presented by them to the Queen—He is now established at the Equerry's table' (Farington, Diary, 7.2667). Edridge aimed to paint individual portraits of families as he moved from house to house in his fashionable circle. But his rarer group portraits, for example, Unknown Gentleman with Children (V&A) or The Vere Poulett Family (Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford), are equally finished productions, often showing the family's interests as painters, musicians, antiquaries, or sportsmen. They seldom include more than three figures. In August 1802 he was at Merton, Surrey, with Sir William and Lady Hamilton, drawing Lord Nelson's portrait; in February 1805 he made a portrait of William Pitt, and in June 1809 William Wilberforce sat to him. He was patronized by such leaders of taste as Sir George Beaumont and Sir John Leicester. On 30 March 1806 Faringtonrecorded that Edridge was able to raise his charge for a full-length portrait drawing from 15 to 20 guineas (ibid., 2706). Neither did he neglect his landscape work, often in pen outline with very sensitive rendering of architecture and great virtuosity in detailing carving and stone. He made several trips abroad at the end of his life, notably to Normandy in 1818 or 1819, and to Paris in 1820, when he specialized in views of the great Gothic churches.

Edridge was quiet and well mannered, and of gentlemanly appearance. A portrait drawing of Edridge by Thomas Monro, formerly in the Panzer collection (reproduced in Houfe) shows a heavy-jowled man of middle age with an aquiline nose, side whiskers, and a good head of hair. Edridge was very anxious to be elected to the Royal Academy, but Farington noted on 18 June 1808 that, as he was a watercolourist, Thomas Lawrencedid not consider Edridge in a line to be admitted (Farington, Diary, 9.3299). He was eventually elected an associate of the Royal Academy in 1820, possibly on the strength of his Normandy landscapes.

Edridge died of heart disease at his home, 65 Margaret Street, London, on 23 April 1821 and was buried on 30 April at Bushey parish church, Hertfordshire. He left a fortune of £12,000 to his widow and executors. Examples of Edridge's work may be found in the National Portrait Gallery, the British Museum (including three sketch-books), and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; Birmingham City Art Gallery; the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle; and Saltram, Devon.

- Simon Houfe DNB