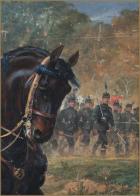

"Richard Caton Woodville / 1914"

Prince, Arthur first duke of Connaught and Strathearn (1850–1942), governor-general of Canada, army officer, and son of Queen Victoria, was born at Buckingham Palace, London, the third son and seventh of the nine children of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, on 1 May 1850, the birthday of his godfather, the duke of Wellington, after whom he was named Arthur William Patrick Albert. His mother's favourite son, from his earliest years, Prince Arthur was destined for a career in the army. In 1858 his father mapped out a scheme for his education and appointed Captain Howard Elphinstone as his governor. The young prince lived in an independent establishment with his governor at Ranger's House, Greenwich, and, on the death of the prince consort in 1861, Elphinstone took an increasingly paternal role in his charge's life. He was influential in leading the prince to acquire an interest in and appreciation of the arts and sciences, with the result that Arthur was more cultivated than either of his elder brothers, the prince of Wales and the duke of Edinburgh.

Prince Arthur's formal military training began on 11 February 1867 when he entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. In 1868 he was commissioned in the Royal Engineers and was subsequently posted to the various arms of the service to give him the broad qualification which might later be useful if, as was expected, he were to succeed the duke of Cambridge as commander-in-chief. His first service abroad was from 1869 to 1870, in Canada with the rifle brigade. On 24 May 1874, he was created duke of Connaught and of Strathearn, and earl of Sussex, and was subsequently known by his first title. In 1876 he was promoted lieutenant-colonel and placed in command of the 1st battalion of the rifle brigade. From 1880 to 1883, as a major-general, he commanded the infantry brigade at Aldershot. His promotion had been accelerated, but he was to show that it had not outstripped his competence. In 1882 he commanded the brigade of guards during the Egyptian campaign, which culminated in Wolseley'sbrilliant victory at Tell al-Kebir against Arabi Pasha's much larger, well-entrenched, and powerfully gunned army. Connaught's brigade was in the second line, but it, and he personally, came under fire during the engagement. He had succeeded in bringing his men to the right place at the right time after an adventurous night march in which much might have gone wrong. Wolseley declared that he had 'taken more care of his men and is more active in the discharge of his duties than any of the generals now with me'. Thus the duke acquitted himself well in battle and became the last British prince to command a significant formation in action.

During the pacification of Egypt, Connaught was governor of Cairo, but he had little taste for that work and was glad in 1883 to embark on service in India, first as a divisional commander and then, from 1886 until 1890, as commander-in-chief of the Bombay army. His area of responsibility extended from Bombay to Aden, but his wish to modernize the Indian armies and to reduce the social gap between the British and the Indian officers and troops was not encouraged by the duke of Cambridge nor, indeed, by almost anyone other than the queen. While in India, he travelled extensively and strenuously throughout the subcontinent carrying out military inspections, and on diplomatic and imperial missions. His interests ranged from improving the efficiency of his forces to concern for the status of women in what he considered a primitive form of society.

In these roles, Connaught excelled and, both before and after he was in India, he discharged them in most quarters of the globe, including the United States, China, Japan, many of the British dominions and colonies, and most of the European countries. He was an excellent public speaker, a welcoming host, and an attentive guest, who found himself more or less at ease with the bey of Tunis, President Taft of the United States, the emperor of Japan, the emperor of Austria, and even Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, his nephew.

On 13 March 1879 Connaught had married Princess Louise Margaret Alexandra Victoria Agnes of Prussia (1860–1917), the third daughter of Prince Frederick Charles of Prussiaand the great-niece of William I of Germany. They had three children; the eldest, Margaret (1882–1920), married the crown prince of Sweden, and had four sons and a daughter; the only son, Arthur (1883–1938), was governor-general of South Africa; and the younger daughter abdicated her royal style in 1919 to become Lady Patricia Ramsay (1886–1974). The Connaughts' marriage was happy and enduring, notwithstanding the duke's affection for Léonie Leslie, the sister of Lady Randolph Churchill, which was shared by his wife.

In 1902 Connaught was promoted field marshal and in 1904 was selected to fill the new post of inspector-general of the forces. The declared purpose of this innovation (which arose from the so-called Esher army reforms), was to provide the newly created army council with eyes and ears; they would sit in their offices and committee rooms and the inspector-general would go out and report what was happening on the ground. Connaught travelled widely among the troops in the United Kingdom and those in the overseas garrisons and he reported as he found, mostly to the effect that the reforms were eyewash. This did not appeal to the army council, nor to the secretary of state for war, and it was decided that the duke, who was too prestigious to be sacked, should be exported. He was, much against his own wish and only on the insistence of his brother, Edward VII, sent to Malta as commander-in-chief and high commissioner in the Mediterranean. Here he found himself, as he had predicted (and quoting his own description), no more than a fifth wheel on the coach; an impediment to, rather than an enhancement of, its efficiency. Much to the annoyance of the king and R. B. Haldane, the secretary of state for war, he resigned in 1909 and so ended his active military service.

Ironically, however, this change brought Connaught towards the summit of his useful career. Edward VII decided that the duke should be governor-general of Canada and to this proposal there was an enthusiastic response from both sides of the Atlantic. Connaught was sworn in as governor-general in Quebec on 13 October 1911. During the next five years, he travelled to every part of the dominion. There was some reserve in French Canada, but in most places he was well-received and he became much better known than any of his predecessors. He established an informal system for seeing the prime minister, Robert Borden, and the ministers of his Conservative government, which had just won a general election. At first, he thought highly of them all, but he soon came to believe that his original impression of healthy enthusiasm and vigour in the minister for militia and defence, Sam Hughes, was more correctly interpreted as self-conceit inflated by an unbalanced mind. This raised very serious issues after the outbreak of war in 1914: with his own army experience, the duke inevitably had strong opinions on military matters, and, despite his constitutional position, he came into conflict with Hughes. The latter insisted on the Canadian troops being equipped with the Canadian-made Ross rifle, and continued to do so after conclusive evidence had been assembled showing that the rifle often jammed after a few rounds when exposed to the conditions of the battlefield. He talked of raising vast Canadian armies of a million men, which Connaught believed would bleed the dominion white, and he turned a blind eye to the recruitment of Americans while the United States was still neutral, contrary to assurances given to the American president by the governor-general. Hughes was also in close accord with Colonel Wesley Allison, long suspected and eventually unmasked as one of the most disagreeable of a number of fraudulent arms profiteers. Thinking that Hughes was a danger to Canada, Connaught pressed Borden to drop him. Borden was probably of the same opinion, but it was not until after the duke had left Canada that he acted on it.

Connaught's attitude has been portrayed as an unconstitutional vendetta, but had he left Sam Hughes to himself, the governor-general would have been failing in his duty to advise, warn, and encourage. When he left Canada in October 1916, there were widespread expressions of regret, not the least from Borden himself.

After Canada, Connaught did not hold any public appointment, but he continued to fulfil public engagements, the most important of which took him in 1921 to India, where he opened the new chamber of princes, the central legislative assembly, and the council of state.

Connaught lived on until 1942, dividing his time between Clarence House in London and Bagshot Park, Surrey, which had been built for him between 1876 and 1879. From 1921 to 1934 he also maintained a villa, Les Bruyères, at St Jean Cap Ferrat, in France, where his garden was regularly opened to members of the navy visiting Villefranche. The duke had received every order which it had been in the power of his mother to bestow, and had received further decorations from Edward VII and George V, and from many foreign powers. He presided over many organizations, including the Royal Society of Arts, the Boy Scouts' Association, and the united lodge of freemasons, and was colonel of three, and colonel-in-chief of nineteen, army regiments. His later years were saddened by the loss of his wife in 1917 and by the death of his elder daughter in 1920 and of his only son in 1938. He died at the age of ninety-one on 16 January 1942 at Bagshot Park and was buried at Frogmore. Oxford DNB Noble Frankland

Woodville, Richard Caton (1856–1927), military artist, the posthumous son of Richard Caton Woodville (1825–1855), an American genre painter of English descent, and his second wife, Antoinette Marie, néeSchnitzler, a portrait painter (whose father, Anton Schnitzler, was German and whose mother was Russian), was born at 57 Stanhope Street, London, on 7 January 1856. Little is known of his early life: the main source, his Random Recollections (1914), is considered unreliable. His mother took him to St Petersburg, and he was educated in Russia and Germany. He studied art at the Royal Academy in Düsseldorf under Professor Evon Gebhardt, a religious painter, from 1876 to 1877, and may have worked in the Paris studio of J. L. Gérôme. He then travelled in the barbaric Balkans.

Back in London in 1877 Woodville offered a drawing to the Illustrated London News (ILN). Its proprietor, William Ingram, liked his work, and Woodville was employed by the ILN for almost his entire working life, though he also contributed to the Boy's Own Paper, Black and White, and other periodicals. He portrayed royalty and ‘society’, and provided illustrations to fiction. However, it was as a military and war artist that he was most employed and best-known. At his London studio he drew for the ILN dramatic, picturesque reconstructions of war scenes, based on imagination and sketches from special artists (precursors of news photographers, sent to draw wars and other newsworthy events), including Melton Prior and Frederic Villiers. He portrayed mostly British imperial wars, and especially heroic charges and last stands. He never experienced battle: in 1882 he reached Egypt after the fighting was over. He was also a successful painter, mostly of incidents from British wars, historical and recent, and from 1879 exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy. He received commissions from Queen Victoria—including The Guards at Tel-el-Kebir (exh. RA, 1884; Royal Collection) and Gordon's memorial service at his ruined palace in Khartoum, the day after the battle of Omdurman (exh. RA, 1899; Royal Collection)—and he was a member of the suite of Prince Albert Victor on the latter's 1889 visit to India. Woodville also had commissions from foreign royalty and Indian princes, and gained high prices.

Woodville's work was popular and was reproduced as prints, in histories, encyclopaedias, and school textbooks, and on postcards and magic lantern slides, becoming for many their images of historical reality. The ILN called him 'an historian in pictorial form of the bravery which has made the English nation what it is' (ILN, 7 Dec 1895, suppl., 3). Although some criticized his work—one critic called it 'an artist's victory over many a British defeat' (Hogarth, 57)—it was also much praised. He was called 'the English Meissonier' (The Times, 18 Aug 1927, 12). Frederic Villiers claimed that he was the best British battle painter, and wrote that 'next to de Neuville and Verestchagin the greatest painter of war pictures is undoubtedly Mr. Caton Woodville … in his pictures is all the real dash and movement of war' (Villiers, 24). Van Goghadmired his depiction of Irish poor in the ILN. In 1882 he was elected to the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours, and Millais said he should be an RA. He received foreign honours, including the French Palmes académiques for his Napoleonic battle scenes, and his work was imitated by others. Reportedly, but for his adultery and divorce he would have received a knighthood. His work has since been attacked for inaccurate portrayal of uniforms and accoutrements.

On 4 October 1877 Woodville married Annie Elizabeth Hill (b. 1854/5), daughter of Rowland Hill, a licensed victualler; they had two sons. Following their divorce in 1893 he married Mrs Nellie Waddington, née Curtis, with whom he had one daughter. His second wife left and divorced him, and by 1911 he was living with Madeleine Adelaide Scott (1876–1926), who passed as his wife. He omitted his wives and children from Who's Who and Random Recollections.

Considered handsome, a dapper man-about-town with a waxed moustache and German accent, Woodville had expensive tastes, moved with a fast bohemian and sporting set, and enjoyed big-game hunting, pig-sticking, fishing, and, it is said, many extramarital affairs. From 1879 he was an officer in the Royal Berkshire yeomanry, the volunteer Royal Engineers, the Royal North Devon hussars, and, finally, the national reserve. He was an enthusiastic imperialist and eulogized British rule in India. He published articles on sport and travel, and in 1914 his lively, name-dropping, and allegedly mendacious memoirs, Random Recollections.

Woodville portrayed the First World War as he had earlier wars: with dramatic charges and heroic stands (later criticized by historians). In 1927 his last major painting, Hallowe'en, 1914: Stand of the London Scottish on Messines Ridge, 31st Oct–1st Nov 1914(1927, London Scottish Regimental Association), was hung in the Royal Academy and by royal command at Buckingham Palace. Madeleine Scott died, aged fifty, on 26 December 1926. Impoverished, ill, depressed, and believing himself 'a finished man' (The Times, 22 Aug 1927, 7), on 17 August 1927 Woodville shot himself in the head with his revolver in his studio attached to his residence, Flat B, Dudley Mansions, 29 Abbey Road, St John's Wood, London: the coroner's verdict was suicide while of unsound mind. He was buried at St Mary's Roman Catholic cemetery, Kensal Green, London. He left only £10 (probate value). Paintings by him are in the Royal Collection, the Tate collection, the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, and elsewhere. Probably more than any other artist, before 1914 Woodville shaped the British public's image of war, especially imperial war.

Oxford DNB Roger T. Stearn