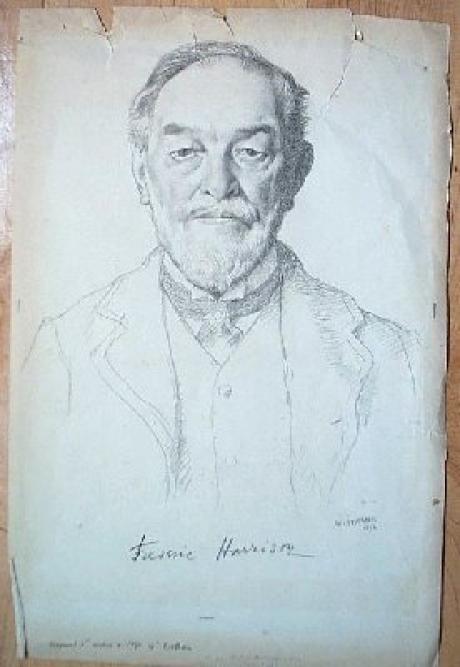

signed and dated "W Strang/ 1912" and further signed by the sitter "Frederic Harrison"

Harrison, Frederic (1831–1923), positivist and author, was born at 17 Euston Square, London, on 18 October 1831, the son of Frederick Harrison (1799–1881), a stockbroker whose father was a prosperous builder from Leicestershire, and his wife, Jane, daughter of Alexander Brice, a Belfast granite merchant. He was baptized in the new St Pancras Church, Euston, and shortly afterwards the family settled in suburban Muswell Hill. His parents undertook his early education and that of his four brothers, born at two-year intervals: Lawrence and Robert Hichens Camden, who would enter their father's firm; and Charles Harrison and William Sidney, later partners in a firm of solicitors. In 1840 the family moved to 22 Oxford Square, Hyde Park, a house designed by Harrison's father. On the advice of Richard Bethell (Lord Westbury), a family friend, Harrison entered Joseph King's day school in St John's Wood. He did so well that when he went on to King's College School, Strand, in 1843, again on Bethell's recommendation, he was placed with boys older than himself.

Given considerable freedom by his teachers, Harrison developed a love of the classics, and on holidays in France an interest in its history and architecture. Stocky in build and energetic, he excelled at sports, especially cricket. He won prizes for Latin and English composition, and performed in school recitations, though he would never speak as well as he wrote. Among his schoolfriends, the most helpful in later years was William Stebbing, an editor of The Times, to which Harrison contributed a number of commissioned articles and over 200 letters.

Second in his school when he left, Harrison entered Oxford in 1849 with a scholarship at Wadham College. He found intellectual companionship with Edward Spencer Beesly, John Henry Bridges, and George Earlam Thorley, who would become warden of Wadham. Harrison later said that he had arrived at Oxford with ‘the remnants of boyish Toryism and orthodoxy’, and left ‘a Republican, a democrat, and a Free-Thinker’ (Autobiographic Memoirs, 1.95). This transformation owed something to the theories of Auguste Comte, which he encountered in works by John Stuart Mill and George Henry Lewes, among others, and later learned were influencing his tutor, Richard Congreve.

Harrison gained only a second class in moderations in 1852, but earned a first in the final school of literae humaniores the next year. Ineligible for honours in the new law and history school, he nevertheless took the examination and received an ‘honorary’ fourth class. He stayed on to assume the tutoring responsibilities relinquished by Congreve, who settled in London to further the cause of Comte's positivist philosophy and Religion of Humanity. Harrison, awarded a fellowship, grew close to such Oxford liberals as A. P. Stanley, Goldwin Smith, Mark Pattison, and Benjamin Jowett.

The summer of 1855 was a turning point in Harrison's life. He arranged an interview with Comte in Paris and was impressed by his insistence upon science as the basis of his new philosophy, outlined in Cours de philosophie positive. Back in London, Harrison tried in a small way to make up for the absence of science in his education. More pressing was his study of law at Lincoln's Inn in fulfilment of a promise to his parents, with whom he lived until his marriage, mostly at 10 Lancaster Gate. His distaste for the practical aspects of the profession was offset by his fascination with Roman law and jurisprudence, which he read with Henry Maine. When Maine's lectures were published as Ancient Law (1861), Harrison praised them in John Chapman's Westminster Review as scientific.

Called to the bar in 1858, Harrison took chambers at 7 New Square, Lincoln's Inn, but spent much of his time on polemical journalism. In 1859 he and Beesly urged British support for Napoleon III's Italian campaign against Austria, and after peace was declared, Harrison visited northern Italy to report for British papers on the aftermath. Later he compared the Risorgimento heroes Cavour and Garibaldi in the Westminster Review. For the same periodical he also released his pent-up antagonism towards the growing latitudinarianism in the church. Why should clergymen who believed hardly more of the creeds than did Congreve continue to enjoy the perquisites of their offices? he asked himself. At Chapman's urging, he wrote ‘Neo-Christianity’ (1860) with the aim of showing that the liberal theology of Essays and Reviews, whose authors included Jowett and Pattison, was inconsistent with the beliefs of most churchmen. In the controversy that followed, one of the bitterest in the Victorian church, he became notorious.

Meanwhile, Harrison had begun teaching history and Latin at the London Working Men's College founded by the Christian socialists in Bloomsbury. His proposal to recast the history syllabus along Comtean lines led the school's founder, F. D. Maurice, to force his resignation. He then taught briefly for the secularist George Jacob Holyoake and at his own expense published his lectures as The Meaning of History (1862), reprinted in The Meaning of History and other Historical Pieces (1894). He was also associated with secularists and Christian socialists in efforts on behalf of the working class. Holyoake provided introductions to friends in Lancashire, whom Harrison visited in 1861 to assess working-class conditions, and again in 1863 to report on the cotton famine resulting from the American Civil War. With Maurice's colleagues Thomas Hughes and J. M. Ludlow he wrote to London newspapers justifying the aims of the striking building trades. In the mid-1860s he defended the ‘new model’ unions of skilled workers against the political economists. His articles in theFortnightly Review much impressed George Eliot, who enlisted his help with legal issues in several of her novels. In 1867 Harrison was appointed to the royal commission on trade unions and wrote its minority report, recommending a secure legal status for unions and protection of their funds, changes in the law that were soon largely enacted. His prestige among labour leaders survived his later criticism of their policies.

Among the political causes that engaged Harrison's pen in the 1860s were Polish independence, the union's position in the American Civil War, and the case against Governor Eyre in Jamaica. Joining a committee headed by Mill [see Jamaica Committee], Harrison condemned Eyre's use of military authority against civilians in 1865, employing arguments that he later directed against British forces in Afghanistan in 1879 and in South Africa during the South African War. He opposed the suspension of habeas corpus in response to the violence of the Fenians, and helped to draw up a petition to parliament demanding that they be treated as political prisoners rather than criminals. In International Policy (1866), a collection of essays edited by him, he called for closer ties with France, and in an essay in Questions for a Reformed Government (1867) he criticized the government's attempt to influence the course of the American Civil War as a betrayal of public sentiment. He made the case for parliamentary reform in working-class papers, but wrote his liveliest essays for the middle-class readers of the Fortnightly Review: ‘Our Venetian constitution’ (March 1867), deriding Walter Bagehot's conservative theories of government; and ‘Culture: a dialogue’ (November 1867), satirizing Matthew Arnold's fear of democracy. Arnold had provoked Harrison's witty dialogue by depicting him as a dangerous radical, once imagining him in a London garden ‘in full evening costume, furbishing up a guillotine’ (Pall Mall Gazette, 22 April 1867, 3).

Though he denigrated the future High Court judge James Fitzjames Stephen for ‘thrusting his huge carcass up the ladder of preferment’ (F. Harrison to John Morley, 28 July 1873, London School of Economics, Harrison MSS), Harrison himself advanced in his profession partly through connections. In 1869 Lord Westbury appointed him secretary to the royal commission for the digest of the law. The next year, on Maine's recommendation, the Council of Legal Education appointed him examiner in jurisprudence, Roman law, and constitutional history; and from 1877 to 1889 he was professor of jurisprudence, international law, and constitutional law for the council. Essays derived from his lectures appeared in the Fortnightly Review and were reprinted in his On Jurisprudence and the Conflict of Laws (1919).

Harrison considered 1870 his annus mirabilis. In that year he found his vocation as a positivist and on 17 August married eighteen-year-old Ethel Bertha Harrison, his first cousin. She supported his decision to join Bridges, Beesly, and the twins Vernon and Godfrey Lushington with others in founding England's first positivist centre, under Congreve. At 19 Chapel Street (now 20 Rugby Street), not far from the working men's college, they offered a smaller version of its free classes. They were especially eager to provide English lessons to refugees from the Paris commune, which the positivists had defended in defiance of middle-class British outrage. They also published a joint translation of Comte's four-volumeSystème de politique positive (1875–7). Harrison undertook the second volume (Social Statics), to the dismay of his father and of Matthew Arnold, who deplored the waste of his literary gifts. At Chapel Street, Congreve introduced an attenuated form of Comte's ritual. The positivists dated letters by Comte's calendar, and it provided the Harrisons with names for their sons, born between 1871 and 1877 and ‘presented’ to the positivist community: Bernard Oliver, Austin Frederic Harrison (1873–1928), Godfrey Denis, and Christopher René. Though the Religion of Humanity was commonly ridiculed as a parody of Christianity, to Harrison it represented the rational final stage of mankind's long religious evolution.

In 1876 Harrison moved his family from their first home, at 1 Southwick Place, London, to 38 Westbourne Terrace. Part of each summer was spent at the elder Harrisons' country house, Sutton Place, a Tudor mansion in Surrey, whose architectural and historical riches Harrison depicted in Annals of an Old Manor House (1893; abridged 1899). From 1888 to 1897 there were also long periods at Blackdown Cottage, Haslemere, Surrey.

In the 1870s Harrison wrote regularly on British and French politics in the Fortnightly Review. Its editor, John Morley, a good but not uncritical friend, helped him plan his first substantial book, Order and Progress (1875), which advocated a strong government but assigned religion, education, and morality to the private sphere. This Comtean division of authority lay behind Harrison's opposition to censorship and his participation in the Liberation Society's campaign to disestablish and disendow the Church of England.

In 1878 long-smouldering dissatisfaction with Congreve's leadership led Harrison, Bridges, Beesly, James Cotter Morison, and the Lushingtons to break with him. Three years later they opened their own positivist centre in Fetter Lane, off Fleet Street, and named it Newton Hall. Pierre Laffitte, head of Comte's Paris disciples, designated Harrison president of the London positivist committee. For two decades Harrison delivered the most important addresses, gratified by the occasional attendance of friends such as Morley, Thomas Hardy, or Wilfrid Blunt. Though repudiating the title of priest, he led prayers to humanity and administered Comte's sacraments, as well as co-ordinating educational and recreational activities, handling funds, and contributing to the French positivists' Revue occidentale and Beesly's Positivist Review. For years he laboured over a vast compendium of biographical sketches of the historical figures named in Comte's calendar, writing 136 of the 599 entries himself. Outside Newton Hall, The New Calendar of Great Men (1892) was largely derided or ignored, but Harrison declared that its selectivity gave it an advantage over his friend Leslie Stephen's Dictionary of National Biography, ‘an interminable snake’ (F. Harrison to John Morley, 31 Jan 1891, London School of Economics, Harrison MSS). No empire-builder, he maintained only loose relations with several small positivist groups in other parts of Britain. Though he made sparks fly with his witty sallies in controversies over positivism with Huxley, James Fitzjames Stephen, John Ruskin, and Herbert Spencer, he could not halt the decline in Newton Hall's small membership after its first decade.

During the last twenty years of the century Harrison was a familiar figure at the Athenaeum and in Liberal circles. A home-ruler, he stood unsuccessfully as a Gladstonian Liberal for London University in the general election of 1886. Local politics proved more congenial. The first London county council elected him alderman in 1889, and as a member of its Progressive Party, led by his brother Charles, he served for five years on important committees, one of which produced early plans for Kingsway. A far-sighted urbanist, he published articles on the London county council's accomplishments and his conception of the ideal city. The Harrisons' views on the family, which reflected both their class and their positivism, led them to help organize a petition against women's suffrage for the Nineteenth Century in 1889, and two years later Harrison debated the issues with Millicent Fawcett in the Fortnightly Review.

In 1880 Harrison befriended the then unknown George Gissing and engaged him as tutor for the two older Harrison boys, though in the end he failed to appreciate Gissing's best novels. Harrison's judgements and reminiscences of other writers are found in The Choice of Books (1886), Studies in Early Victorian Literature (1895), and Tennyson, Ruskin, Mill and other Literary Estimates (1899). Invited by Macmillan, the publisher of these volumes, to write the popular studies Oliver Cromwell (1888) and William the Silent (1897), he proved adept at assimilating secondary sources. When his last child, a girl, was born in 1886, he named her Olive. Later he helped organize celebrations honouring Gibbon and Alfred the Great. Trips to France, Italy, and the Mediterranean yielded essays informed by his wide historical knowledge. After a lecture tour in the United States he published George Washington and other American Addresses (1901).

In 1902 Newton Hall's lease expired and the Harrisons settled at Elm Hill, Hawkhurst, Kent. Others carried on a diminished positivist programme in hired rooms. Harrison's attention lay elsewhere. He became a JP and held offices in the Royal Historical Society, the Sociological Society, the Eastern Question Association, and the London Library. John Ruskinappeared in 1902, and Chatham in 1905. His only novel, Theophano: the Crusade of the Tenth Century (1904), and a drama in blank verse, Nicephorus: a Tragedy of New Rome(1906), were unsuccessful offshoots of research on Byzantine history for his Rede lecture at Cambridge in 1900. Between 1906 and 1908 he compiled six volumes of essays, including his recollections of mountaineering, My Alpine Jubilee, 1851–1907 (1908). His Autobiographic Memoirs appeared in 1911, informative but disappointing as literature. Among my Books (1912) reprinted essays from the English Review of his son Austin, and much of The Positive Evolution of Religion (1913) originated in the Positivist Review.

In 1912 the Harrisons moved to 10 Royal Crescent, Bath. During the war Harrison published The German Peril, which embodied fears dating back to the 1860s. His youngest son died in France of battle wounds in 1915, with his father at the bedside. Ethel died in 1916. Harrison, still vigorous and opinionated, went on to produce four more volumes of reprinted essays and commentary on current affairs. He died suddenly from heart failure at his home in Royal Crescent on 14 January 1923. He had received honorary degrees from three universities—Cambridge (1905), Aberdeen (1909), and Oxford (1910)—and the freedom of the city of Bath (1921). Wadham had made him an honorary fellow in 1899, and after his death an urn containing his ashes, mingled with Ethel's, was placed in the college ante-chapel.

Martha S. Vogeler DNB

William Strang, (1859–1921), painter and printmaker, was born at Dumbarton, on 13 February 1859, the younger of the two sons of Peter Strang, a builder, of Dumbarton, and his wife, Janet Denny. He attended Dumbarton Academy and entered the Slade School of Art at the age of seventeen. He was to remain in London for the rest of his life. In 1875 Alphonse Legros succeeded Edward Poynter as Slade professor of fine art at University College, London, and his influence was to be deep and lasting on Strang's art. Under Legros, Strang took up etching and, although he continued to paint, printmaking dominated his œuvre until the turn of the century. It was as an etcher of imaginative compositions, in which homeliness and realism, often imbued with a macabre or fantastic element, were subdued to fine design and severe drawing, that he first made a name. He signed his prints ‘W Strang’. The illustrations to Death and the Ploughman's Wife (1888) and The Earth Fiend (1892), two ballads written by himself, and those to The Pilgrim's Progress (1885) contain some of the best of his earlier etchings.

Strang's strong personal interest in social issues grew alongside the rapid development of organized socialism in the 1880s and 1890s. His print The Socialists (1891) shows the artist among the people, listening intently to the impassioned orator. His membership of the Art-Workers' Guild in 1895 and close association with C. R. Ashbee and the Essex House Press established his commitment within its natural artistic and professional context. In 1885 he married Agnes McSymon, the daughter of David Rogerson JP, provost of Dumbarton; they had four sons (two of whom, Ian and David, were also printmakers) and one daughter.

Among Strang's numerous single plates the portraits are especially good, though these were to be surpassed as the artist acquired more confident mastery and a broader style, tending to exchange the use of acid for dry point or mezzotint. The best of the later portraits are masterpieces of their kind. Among later sets of etchings are the illustrations to The Ancient Mariner (1896), Kipling's Short Stories (1900), and Don Quixote (1902). A catalogue of Strang's etched work, published in 1906, with supplements (1912 and 1923), contains small reproductions of all his plates, 747 altogether. He designed and cut one of the largest woodcuts ever made, The Plough, which measures almost 5 by 6 feet. The impression in the Victoria and Albert Museum is dated 1899 and was published and sold by the Art for Schools Association, Bloomsbury.

During the latter part of his life Strang etched less and painted more, and much of his time was given also to portrait drawings executed in a style founded on the Holbein drawings at Windsor. He undertook a great number of these, and his sitters, many of the most distinguished people of his time, included Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1908), Lord Kitchener (1910), the young Edward, prince of Wales (1909), and Thomas Hardy; his etching of the novelist became in the late twentieth century something of an icon. As a painter Strang experimented in many styles, but at his best was highly original. Bank Holiday (1912), in the Tate collection, and the Portrait of a Lady (Vita Sackville-West, 1918), at Glasgow, are good examples of his clean, bright colour and rigorous drawing. The Tate collection also holds two self-portraits (1912, 1919) and one landscape. The British Museum has 136 of the etchings, and an important collection of Strang's graphic work is in the Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow.

Strang was elected ARA in 1906, RA (as an engraver) in 1921, and president of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters, and Gravers in 1918. He was of medium height and strongly built. Outspoken and combative in argument, he delighted in good company, conversation, and fun. He often travelled on the continent, and visited the United States. He produced many self-portraits, etched, drawn, and painted, in a variety of guises. He died suddenly of heart failure at the Brinklea Private Hotel, Bournemouth, on 12 April 1921.

Strang has suffered for being ‘unclassifiable’ in the history of early twentieth-century British art. An exhibition of his work, held in 1981 in Sheffield, Glasgow, and the National Portrait Gallery, went some way to re-establish the reputation of this most singular of image makers. He was an artist who combined a febrile imagination with formidable technical ability and a penetrating eye with a mordant wit, perhaps most clearly evident in his Bal Suzette (1913).

Laurence Binyon, rev. Anne L. Goodchild DNB