"Robert Russell"

Gill, (Arthur) Eric Rowton (1882–1940), artist, craftsman, and social critic, was born at 32 Hamilton Road, Brighton, Sussex, on 22 February 1882, the eldest son and second of the thirteen children of the Revd Arthur Tidman Gill (1848–1933), minister of the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion, a Calvinist Methodist church, and his wife, (Cicely) Rose King (d. 1929), formerly a professional singer of light opera under the name Rose le Roi. His younger brother, Leslie MacDonald [Max] Gill became a noted decorative cartographer. Arthur Tidman Gill, who came from a long line of Congregational missionaries and had been born in the South Seas, had himself been a Congregational minister, but had recently left the church of his forebears, after doctrinal disagreements, to join the connexion. Eric Gill was brought up in an atmosphere of religious controversy and holy poverty that helped shape his own valiant, if not totally successful, ambition 'to make a cell of good living in the chaos of our world' (Gill, Autobiography, 282).

Gill became the greatest artist–craftsman of the twentieth century: a letter-cutter and type designer of genius, whose Gill Sans and Perpetua typefaces have continued in world-wide use for many decades; a sculptor whose powerful work initiated a return to the directness of hand carving; a draughtsman and wood-engraver of consummate subtlety and skill. In any one of these crafts Gill would be considered a prime practitioner. He was also a copious essayist and a vociferous polemicist. The energy and spread of his activity, underpinned by a fervent belief in the values of making by hand as a bastion against the dehumanizing forces of industrialization, make his achievement comparable with that of William Morris in the century before.

Brighton and Chichester, 1882–1899

Eric, named after the hero of Dean Farrar's moralistic school story Eric, or, Little by Little, later wrote affectionately of his early childhood, spent in a succession of small, tightly packed houses near the railway line in Brighton where Eric—always to be an admirer of functional engineering design—watched and drew the trains. He went intermittently to a local kindergarten kept by the Misses Browne, sisters of the Dickensillustrator Hablot K. Browne (Phiz). He then spent seven years at Arnold House, a traditional boys' preparatory school in Hove where he was 'fairly happy', although poor to mediocre in all academic subjects except arithmetic. In retrospect the uninspired regime at Arnold House quite suited his developing iconoclasm: 'I was taught nothing in such a way as to make it difficult to discard' (Gill, Autobiography, 24).

Gill's unashamed fascination with the bodily functions, especially the sexual, surfaced early. Towards the end of his schooldays, he discovered the splendours of the male erection: 'how shall I ever forget the strange, inexplicable rapture of my first experience? What marvellous thing was this that suddenly transformed a mere water tap into a pillar of fire—and water into an elixir of life?' (Gill, Autobiography, 53). His struggles to reconcile the flesh and spirit determined his later life, his writings, and his art.

In 1897 the Gill family moved to 2 North Walls, Chichester. Arthur Tidman Gill had now joined the Church of England. Eric enrolled at the Chichester Technical and Art School, where he was befriended and encouraged by the art master George Herbert Catt, winning a queen's prize for perspective drawing. But the examination-dominated art school training, designed to produce more art teachers, was irksome to a student of Gill's wide-ranging curiosity. He learned more from his explorations of Chichester itself, the serene historic city, 'clear and clean and rational', contained within its Roman walls (Gill, Autobiography, 81). Chichester became Gill's model of the ideal city. The architecture of Chichester Cathedral entranced him. The two famous early Norman relief panels set into the interior have an obvious influence on the linearity of Gill's own later sculpture. At the age of seventeen he fell precociously in love with the cathedral sacristan's daughter Ethel Hester Moore (1878–1961), a fellow student at the Art School, and they embarked on a long engagement, which was not without its tensions.

London, 1900–1907

Gill described the next few years, in which he moved to London to train as an architect in the office of W. D. Caroë, architect to the ecclesiastical commissioners, as 'a period of all-round iconoclasm' (Gill, Autobiography, 94). His discontent was exacerbated by his lingering grief over the death in 1897 of his favourite sister, Cicely. His disillusionment with architecture as experienced in Caroë's prosperous, complacent Anglican churchpractice in Whitehall Place, Westminster, was profound. The lack of contact between gentlemen architects and artisan builders offended his ideas of human dignity and contravened the theories of creative integration he was already formulating at this time.

Gill found relief in agnosticism, socialism, and the crafts, escaping from the recommended evening lectures in architecture to take classes in masonry at the Westminster Technical Institute and calligraphy at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, a school founded in 1896 on revolutionary principles of practical training in technical skills. The co-principal was W. R. Lethaby, whom Gill was to acknowledge as one of the great men of the nineteenth century, one of the few whose minds were enlightened directly by the Holy Spirit.

Gill's enthusiasm for lettering dated back to his childhood: early drawings of trains (in West Sussex Record Office) show how meticulously he drew out the engine names. These skills had been developed in Caroë's office, where he provided lettering for architectural drawings. But Gill's sense of the real possibilities of letters was awakened only when he joined Edward Johnston's classes at the Central School. His first sight of the skilful, dedicated Johnston writing in script, using a quill pen, came as a revelation: 'I was struck by lightning, as by a sort of enlightenment. It was no mere dexterity that transported me; it was as though a secret of heaven was being revealed' (Gill, Autobiography, 119).

In 1902 Gill moved out of his lodgings in Clapham to join Edward Johnston in his bachelor rooms at 16 Old Buildings, Lincoln's Inn. By 1903 a number of commissions for inscriptional carvings on tombstones and memorial tablets convinced him that he could make a living from letter-cutting and monumental masonry: 'I managed to hit on something which no one else was doing and which quite a lot of people wanted' (Gill, Autobiography, 117). He gave up his pupillage with Caroë and confidently married Ethel, known lovingly as Ettie, in the sub-deanery church of St Peter in Chichester on 6 August 1904. His father officiated at the ceremony.

'Eric Gill, Calligrapher', as he was entered in the register, started married life in a small tenement flat in Battersea Bridge Buildings, moving in 1905 to 20 Black Lion Lane in Hammersmith, close to Kelmscott House, once the home of William Morris, and to Morris's Kelmscott Press. Hammersmith was still an enclave of the arts and crafts, and especially the printing crafts. The Gills' move had been precipitated by the birth of their first child, Elizabeth (Betty), on 1 June 1905; a second daughter, Petra, followed on 18 August 1906.

Gill had acquired an important German client, Count Harry Kessler, a connoisseur of printing, who commissioned him to design the title-pages for a special edition of Goethe's Schiller, to be published by Insel Verlag, Leipzig. This and subsequent commissions from Kessler brought Gill a new involvement with fine print. In 1906 he started wood-engraving. He returned to the Central School, this time as a teacher, and was also giving classes in masonry and lettering to stonemasons at the Paddington Institute.

In this hopeful period of relative prosperity, Gill took on his first apprentice, Joseph Cribb, and he and Ethel felt able to afford a maid-of-all-work, Lizzie, whose duties soon included sleeping with her master. 'First time of fornication since marriage', runs a characteristically accurate and candid entry in his diary for 14 June 1906 (diary, University of California, Los Angeles). He also acquired the first of many mistresses, Lillian Meacham, with whom in 1907, in spite of Ethel's disapproval, he set off on an ecstatic architectural visit to the cathedral in Chartres.

Though by now well known in London art and socialist circles, a member of the Fabian Society, the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, the Art-Workers' Guild, Gill'siconoclasm and uncouthness set him apart from the cliquish craftsman followers of Morris. He remained to a great extent an outsider, an extremist—in his own later words, the stranger in a strange land. In the summer of 1907 he struck out on his own again, resettling his workshop, wife, and children in the countryside, acting out his conviction that 'life and work and love and the bringing up of a family and clothes and social virtues and food and houses and games and songs and books should all be in the soup together' (Gill, introduction to Engravings, 1929). Gill's move to Sussex was the first of several attempts to create the idyllically integrated life.

Ditchling village, 1907–1913

Gill's first six years in Ditchling were spent at Sopers, a small brick house in the main street of the village. He set up his workshop alongside the house. At this period Gillbranched out from letter-cutting to sculpture. His first carving in stone, Estin Thalassa, of the maiden of the eternal seas, was made in late 1909, a time of 'comparative continence' while Ethel was pregnant with their third daughter, Joanna, born on 1 February 1910. Gill regarded the creation of his substitute woman of stone as a natural development from inscriptional carving: this new job was the same job, only the letters were different ones. 'A new alphabet—the word was made flesh' (Gill, Autobiography, 159).

Gill's approach to sculpture was essentially a craftsman's in its directness and its feeling for materials. He rejected the usual 'modelling-and-pointing machine' techniques, whereby the sculptor's clay model was enlarged by mechanical means by an artisan assistant, disliking the division of labour this entailed. The primitive power of Gill's early carvings drew admiration not only from Count Kessler but also from Roger Fry and William Rothenstein. Through Rothenstein, Gill met the philosopher and critic Ananda Coomaraswamy, expert in the arts and crafts of India, and eagerly absorbed Coomaraswamy's theories of the essential sacredness of sensual art. Coomaraswamy's aphorism 'An artist is not a special kind of man, but every man is a special kind of artist' (The Transformation of Nature in Art, 1934, 64) was quoted by Gillso often most people have imagined Gill originated it.

Count Kessler had arranged for Gill to become an apprentice–assistant to the famous French sculptor Aristide Maillol. Gill went to visit Maillol in Marly-le-Roi but realized quickly that their methods were incompatible. His allegiances were now with Jacob Epstein, Augustus John, and a small group of radical young London artists anxious to form a community based on the 'new religion', with quasi-primitive emphasis on sun worship and worship of the fecund female body. Until it exploded into the acrimony that ended many of Eric Gill's male relationships, his friendship with Epstein was particularly close, and together they planned a sequence of immense carved human figures looming over the Sussex landscape like a twentieth-century Stonehenge. This grandiose configuration did not materialize.

Gill himself, with his peculiar combination of the mischievous and solemn, was pushing out the boundaries between the acceptable and unacceptable, in personal behaviour as in art. His sister Gladys and her husband, Ernest Laughton, were the models for the realistic carving which Gill entitled Fucking (1911). (This work, retitled Ecstasy, is now in the Tate collection.) While the sculpture was in progress, Gill was embarking on the incestuous relationship with Gladys that continued for most of his adult life. It is almost certain he had sexual relations with his sister Angela, and possibly with other sisters too. Another carving of this period, Votes for Women (1910), shows the act of intercourse with woman ascendant, man kneeling to receive her. It was bought for £5 by Maynard Keynes. When his brother asked him how his staff reacted, Keynes replied, 'My staff are trained not to believe their eyes' (MacCarthy, 104).

In January 1911 Eric Gill's first one-man exhibition of stone carvings was held at the Chenil Gallery in Chelsea. It was well reviewed. Gill's small mother-and-child figures made an especially strong impression on the critic Arthur Clutton-Brock, who praised the 'simplicity and force' with which Gill expressed the instinct of maternity (The Times, 17 Jan 1911). Two relief carvings—Crucifixion and A Roland for an Oliver—were purchased by the Contemporary Art Society. The following year Gill received a commission from Madame Strindberg for designs for her soon notorious new nightclub, the Cave of the Golden Calf, off Regent Street. His spectacularly phallic calf was the motif recurring on the membership card and the bas-relief hung at the entrance of the club, finally appearing in three-dimensional form, gilded and mounted on a pedestal. Gill's resplendent Golden Calf was among seven of his sculptures shown in Roger Fry's ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’.

Gill had growing misgivings about his success in the London ‘high art’ world, which he came to regard as a corrupt and, to a serious artist, a demeaning system dependent 'upon the ability of art dealers, assisted by art-critics, to preserve a hot-house culture in the midst of an inhuman and anti-human industrialism' (Gill, Autobiography, 177). It offended his religious sensitivities. Gill was now emerging from his period of strident agnosticism followed by Nietzscheism, and gradually moving towards Roman Catholicism. In 1911 he visited the abbey of Mont César in Louvain, where his first experience of hearing monastic plainchant brought him to an overwhelming moment of religious certitude: 'I knew, infallibly, that God existed and was a living God—just as I knew him in the answering smile of a child or in the living words of Christ' (ibid., 187). On 22 February 1913 he and his wife—who now took the name of Mary—went to Brighton to be received into the Roman Catholic church.

Ditchling Common, 1913–1924

In the year of his conversion Gill and his family moved out to Ditchling Common, 2 miles north of the village. Here their house, Hopkins Crank, had outbuildings and farming land. Gill was intent on a life of medieval self-sufficiency in which the family produced its own food, baked its bread, made its own clothes, and educated its daughters at home. Gill's apprentice Joseph Cribb also became a Roman Catholic. As other Catholic craft workers were attracted to the common, it became an enclave of determinedly unworldly attitudes to life, combining fervent work and worship. As described by one resident, Gill at Ditchling had reverted to 'a fascinating sort of communal early Christianity' (P. Anson, Aylesford Review, spring 1965).

Gill's new Catholic credentials qualified him for the substantial commission, in 1913, for the fourteen carved stone stations of the cross for Westminster Cathedral. These occupied him for the next five years, exempting him from service in the First World War. The Westminster stations, controversial in their day on account of their painful rawness, now appear among the most impressive of Gill's large-scale sculptural works. He was his own model for Christ in the tenth station, having drawn his portrait in the mirror. Gill was to carve further sequences of stations for St Cuthbert's Church in Bradford, commissioned by his friend Father John O'Connor in 1921, and for St Alban's, Oxford, in 1938.

The early years on Ditchling Common saw a surge of activity in the graphic arts. Gillwas stimulated, first, by the arrival in Ditchling of Edward Johnston, with whom he co-operated in the development of sans serif lettering for London Underground, precursor of Gill's own famous sans serif type design. In 1915 they were joined by Douglas (later Hilary) Pepler, whom both had known in Hammersmith. Pepler brought with him a Stanhope hand press, which had once belonged to William Morris, and in 1916 founded St Dominic's Press, the most ebullient if not the most technically sophisticated of the private presses of the period. It drew much of its character from Gill's engravings and his marvellous dexterity in combining the type and the image on the page. Together he and Pepler printed books and pro-Catholic, anti-capitalist pamphlets, which they distributed by hand, and combined in producing the idiosyncratic magazine The Game. It was, for a time, an all-involving friendship. 'Those are pleasant days', wrote Gill, 'when young men and men in the prime of their life argue and debate about the divine mysteries and concoct great schemes for the building of new societies, and they were pleasant days for us' (Gill, Autobiography, 206).

Eric Gill, with his intense respect for the male hierarchies, was anxious for a son. After a history of miscarriages, Mary was now unlikely to conceive, and in the autumn of 1917 the Gills took in an eight-month-old boy, an illegitimate child from an infants' home in Haywards Heath. He was not legally adopted, but was known as Gordian Gill and brought up as the Gills' son.

The following summer Gill was finally called up and spent the last few months of the war as a driver in the RAF mechanical transport camp at Blandford, Dorset, enduring military service with a tolerance curiously at odds with his later pacifist stance. From the end of the First World War, war memorials formed the staple of Gill's major sculptural commissions, the most impressive being those at Bryantspuddle (1918), Chirk and South Harting (1919), Trumpington, near Cambridge, and the huge lettered wall panel recording 228 names of the fallen in the ante-chapel at New College, Oxford (both 1921).

Over the war years Gill had become closely involved with the Dominican order, and in particular with Father Vincent McNabb, a forceful Dominican priest whom he first met at a luncheon party in Edinburgh in 1914. Influenced by Father Vincent, Eric Gill, his wife, Mary, Hilary Pepler, and Gill's new protégé–apprentice Desmond Chute, became members of the third order of St Dominic, the lay order of the Dominicans. In January 1919 at Hawkesyard Priory, Gill 'put on the habit' for the first time. He took to wearing the girdle of chastity with his monastic dress. 'Much good it did him', said a cynical friend (MacCarthy, 143).

The Catholic craft community at Ditchling now developed energetically, in accordance with Father Vincent's dictum that there can be no mysticism without asceticism. Ditchling Common was marked out as a place of austere holiness by the Spoil Bank Cross, a large wooden calvary erected on a hillock beside the London to Brighton railway line. At the centre of the complex of workshops was the chapel, designed by Gill, now prior of the order, where the office was said at regular intervals through the working day.

Philosophically, Ditchling was underpinned by the theories of the French Roman Catholic intellectual Jacques Maritain, great twentieth-century interpreter of St Thomas Aquinas, whose Art et scolastique was published in its new English translation as Art and Scholasticism at the St Dominic's Press. The craft Guild of Sts Joseph and Dominic was founded on the premise that all work is ordained by God and is therefore divine worship. The members, obeying distributist tenets of individual responsibility, owned their own tools, workshops, and the products of their work. By 1922 forty-one Catholics were living and working on the common. Some were professional craftspeople. Some were lost young men of the post-war generation, in search of a vocation. Among these was the artist David Jones.

Ditchling became a place of pilgrimage, an inspiring demonstration of Catholic family values. One visitor was convinced he saw a nimbus around Gill's head and shoulders as he sat at table. The realities of Ditchling life were not so reassuring. Entries in Gill'sprivate diaries, made public in 1989, show repeated incidents of incest with his elder daughters Betty and Petra, a pattern of behaviour also said to have been present in his father, Arthur Tidman Gill. At this same period Gill was making a series of nude drawings of his teenage daughter Petra which were the basis of the most exquisite of his wood-engravings. One of Gill's favourite sayings was 'It all goes together' (E. Gill, Last Essays, 1942, 176). But there was an increasingly obvious dichotomy between his public persona and private morality.

Gill's justification for sexual latitude was that sexual pleasure was an aspect of worship. 'Man is matter and spirit—both real and both good' (E. Gill, In a Strange Land, 1944, 152). He developed an elaborate theory of human love as the participation in and glorification of divine love. The erect phallus had a powerful symbolism as the image of God's potency. Gill's own holy pictures acquired a new sexual candour alarming to many of his previous admirers: especially scandalous was his wood-engraving The Nuptials of God (1922), depicting Christ on the cross in the voluptuous embrace of his bride, the Roman Catholic church. Gill courted further controversy with his Leeds University war memorial Christ Driving the Moneychangers from the Temple (1923), a blatantly tactless attack on capitalist commercialism.

In 1924 Gill resigned from the Guild of Sts Joseph and Dominic and the family left Ditchling, peremptorily and finally. The ostensible reason was that Gill had found so many visitors intrusive. Stronger motivations were a bitter quarrel with Pepler over guild finances, and Gill's resentment of the love affair between his daughter Betty and Pepler's son David, to whose marriage he finally, reluctantly assented in 1927.

Capel-y-ffin, 1924–1928

In August 1924 the Gills and a small entourage of followers and animals arrived at the former Benedictine monastery at Capel-y-ffin in the Black Mountains of Wales. The place had been chosen by Gill for its beauty and remoteness, 14 miles from Abergavenny and 10 from the nearest railway station. The rural isolation gave scope to Eric Gill's contemplative and analytic urges: he began to articulate the views on art and society, religion and sex, that poured out into his writings over the next decade. If Ditchling had been the period of his 'spiritual schooldays', then Capel represented 'spiritual puberty' (Gill, Autobiography, 223).

Gill, in his early forties, had lost the youthful scrubbiness that alienated some of his contemporaries and was already taking on the appearance of the patriarch, customarily dressed in a belted knee-length rough tweed tunic, which many mistook for a monk's habit, and often to be seen in the stonemason's traditional square folded paper hat. Count Harry Kessler, resuming the collaboration with Gill that had been severed by the First World War, now found him 'a Tolstoy-like figure in smock and cloak, half monk, half peasant' (H. Kessler, Diary of a Cosmopolitan, 1971, entry for 20 Jan 1925). Gill'sspecial form of rational dress, the charm and persuasiveness of his personality, and his extraordinary quality of concentration come over in a series of portrait photographs taken at Capel-y-ffin by Howard Coster and now in the National Portrait Gallery.

Artistically, the four years at Capel were productive. Although facilities for carving large works were non-existent, and the monolithic female figure named Mankind (1928) was made in a borrowed studio in Chelsea, some of Gill's most beautiful and engaging smaller carvings emanate from Capel. They include the lovely sequence of naiads with frondy hair; the vulnerable image of The Sleeping Christ (1925); the black marble torso entitled Deposition (1925), now at King's School, Canterbury, described by Gill as 'about the only carving of mine I'm not sorry about' (Gill, Autobiography, 219). In Wales he also completed his only substantial carving in wood, the war memorial altarpiece in oak relief for Rossall School (1927).

Gill's wood-engraving burgeoned in the mid-1920s. At Capel he began printing his own engravings, experimenting with a copperplate press, and he started an enormously successful and enjoyable collaboration with Robert Gibbings, proprietor of the Golden Cockerel Press, and his wife, Moira. With Gill's insistence on the merging of work with leisure, this became a tripartite amatory collaboration too. The most important Golden Cockerel editions for which Eric Gill provided the engravings were The Song of Songs(1925), Troilus and Criseyde (1927), The Canterbury Tales (1928), and The Four Gospels of 1931—Gill's and Gibbings's tour de force. No other wood-engraver of the period comes near to Gill's originality and verve. But, once again, the explicit eroticism of The Song of Songs and of Gill's later illustrations for E. Powys Mather's Procreant Hymn of 1926 shocked many of his former supporters and drew puzzled reproaches from the Dominicans.

The most influential of Gill's commissions at Capel-y-ffin came from his fellow Catholic Stanley Morison, typographic adviser to the Monotype Corporation. The typefaces designed by Gill for Monotype— Perpetua (1925), Gill Sans-serif (1927 onwards), Solus (1929)—remain his greatest achievement: ironically so, since they were designed for the machine production Gill so despised. Gill Sans can be considered the first truly modern typeface, and it had a lasting impact on twentieth-century European type design.

Gill, devotee of the excursion, made long-ranging expeditions out from the Black Mountains: to Rome in 1925, to Paris in 1926. He made several visits to Salies-de-Béarn, a spa town in the Pyrenees. The family spent winter 1926–7 there, staying in the house belonging to Gill's current secretary–mistress–model, Elizabeth Bill. Miss Billand her elderly fiancé were also of the household. Salies-de-Béarn became established in Gill's pantheon as an ideal little city, active, religious, decorous, of a kind that, in Britain, was ceasing to exist.

Pigotts, 1928–1940

In October 1928 Gill made his final move: to Pigotts, near Speen, 5 miles from High Wycombe. The quadrangular assembly of local redbrick farm buildings, with an ancient pigsty in the centre, made a more practical environment than Capel-y-ffin for work that now derived increasingly from London. Gill's 1928 solo exhibition at the Goupil Gallery was critically and financially successful, and he had recently been commissioned by the architect Charles Holden to lead the team of sculptors working on the London Underground headquarters at St James's Park. The regime at Pigotts was less that of the formalized religious community, more that of the devout extended family, with its chapel and resident chaplain. The Gills' second daughter, Petra, lived at Pigotts after her marriage, in 1930, to Denis Tegetmeier, the engraver and cartoonist, as did their youngest daughter, Joanna, and her husband, René Hague. Gill set up the Hague and Gill press with his son-in-law in 1931.

The Pigotts years were dominated by a number of large-scale commissions for sculpture which brought Gill increasingly into the public eye. The popular press identified his ambiguity, referring to him as 'the Married Monk'. In 1931 he began his famous series of carvings for the new BBC building in London, culminating in the giant figures of Shakespeare's Prospero and Ariel above the portals, transformed by Gill into God the Father and Son. After public complaints to the BBC governors about the size of Ariel's genitals, the headmaster of a well-known public school was brought in to adjudicate, and Gill was instructed to reduce them in scale. In 1933 he provided decorations for Oliver Hill's modernist Midland Hotel at Morecambe: the big stone relief for the dining room, Odysseus Welcomed from the Sea by Nausicaa, shows Gill in his most supple and inventive mid-1930s mode.

In 1934 Gill travelled to Jerusalem, to carve reliefs on the new archaeological museum; his first visit to the Holy Land impressed him deeply. In 1935 the British government commissioned him to carve a large relief for the assembly hall of the new League of Nations building in Geneva. His original proposal, for an international version of his controversial Leeds Moneychangers carving, did not find favour, and Gill substituted a grandiose but no less politically charged design influenced by Michelangelo, depicting the 're-creation of man by God' (Collins, 211). He finished the 9 metre three-panel relief in situ and attended the unveiling in August 1938.

The nature of Gill's workshop had altered fundamentally. Laurie Cribb, brother of Joseph, a supremely skilled letter-cutter who had come with Gill from Capel, remained his much-valued personal assistant. But there was now a changing population of pupil–assistants, not necessarily Catholic. The structure was more formal. Gill called them by their forenames; they called him Sir. Visitors compared the atmosphere to that of a Renaissance atelier. Many of Gill's apprentices—notably Donald Potter, Walter Ritchie, David Kindersley, and Ralph Beyer—became well-known sculptors and letter-cutters in their own right. Gill's nephew, the sculptor John Skelton, joined the workshop as a trainee in the final months before Gill's death.

In the 1930s Gill designed five more typefaces: Golden Cockerel Roman (1930) for Robert Gibbings; Joanna (1930), designed originally for Hague and Gill, later adapted for machine production by Monotype; Aries (1932) for Fairfax Hall's private Stourton Press; Jubilee (1934) for Stephenson Blake; and Bunyan (1934) for Hague and Gill, a version of which was issued under the name Pilgrim by Linotype in 1953. Joanna, named in honour of his youngest daughter, is considered by many specialists to be the finest of all Gill's type designs. He also designed Hebrew and Arabic typefaces. His informative and sprightly Introduction to Typography was published in 1931. The Post Office commissioned Gill to provide lettering for stamps of the values ½d. to 6d. issued for George VI's coronation in 1937. He continued wood-engraving, Gill's bookplates for his friends being among the most delightful of his works.

Eric Gill had an unusual ability for working in both two and three dimensions, and on variable scales. At this same period he returned to architecture, replanning and rebuilding with the boys of Blundell's School at Tiverton a chapel with a central altar (1938), designed with the aim of democratizing churchgoers' participation in the mass—a radical and influential innovation. The same plan was adopted for St Peter's, Gorleston-on-Sea, in Norfolk, the only complete building designed by Eric Gill. This austere and quasi-primitive Roman Catholic church was built in brick by local craftsmen, with curved arches forming an octagonal centre space.

Gill's published essays and lectures, spasmodic in his early days, became a steady stream, beginning with Art-Nonsense in 1929. The frontispiece of this book is designed around a version of Gill's Belle sauvage wood-engraving, showing a nude woman emerging from a thicket, for which the model was Mrs Beatrice Warde, American-born publicity manager to Monotype. Warde, for years Gill's intellectual sparring partner and his lover, was the most sophisticated of the women in his life.

Gill's next books Art and a Changing Civilisation and Money and Morals followed in 1934; Work and Leisure in 1935; The Necessity of Belief, Gill's most considered and convincing argument of faith, in 1936; Work and Property in 1937. Eric Gill's Last Essays was published posthumously in 1942, and a further collection, In a Strange Land, in 1944.

In a sense, these books were all the same book, imbued with Gill's peculiar blend of Ruskinian morality, William Morris utopianism, Thomist philosophy, and bumptious common sense, whether arguing pro-nudity and sunbathing or anti-contraception ('masturbation à deux') and the wearing of trousers on the grounds that these constricted and dishonoured 'man's most precious ornament' (E. Gill, Trousers, 1937). Though Gill's private conversation could be gentle and delicious, his forceful repetitiousness in public was compared by D. H. Lawrence to that of a workman 'argefying' in a pub (Book Collector's Quarterly, October 1933).

In the mid-1930s Gill's views moved further leftward, driven by his sense that the logical conclusion of Catholicism could only be a form of communism. He joined the Artists' International Association, the Christian Arts International, PAX, the Peace Pledge Union, becoming a familiar figure on the anti-fascist protest platforms of the period, 'speaking in a light voice, with a dry wit, above his Biblical beard' (News Chronicle, 8 Jan 1938). Gill's support for workers' control of the means of production and, as the Second World War drew nearer, his high-profile support for pacifism brought him into direct confrontation with the Roman Catholic church.

Gradually, Gill's health was breaking down. In 1930 he spent several weeks in hospital following a mysterious nervous collapse. A succession of illnesses and accidents assailed him after his return from Jerusalem, exacerbated by his arduous workload and growing financial worries in supporting his multitude of dependants: the Gills had eleven grandchildren by the end of the decade. His son Gordian had disappointed Gill'sexpectations, and a permanent rift arose between them after Gordian discovered by accident that he had been adopted. Domestic dramas were intense as Gill fell in love again—with Daisy Hawkins, teenage daughter of the Gills' housekeeper, an affair he pursued in tandem with a longer-standing sexual relationship with May Reeves, the schoolmistress at Pigotts. Gill's passionate and yearning love for Daisy, who was eventually banished by Mary to Capel-y-ffin, is captured in the many drawings he made of her, published in Twenty-Five Nudes (1938) and Drawings from Life (1940).

Gill became an honorary associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1935, a royal designer for industry in 1936, an associate of the Royal Academy in 1937. His acceptance of honours from just the establishment art institutions he had formerly despised can be read as symptomatic of his increasing exhaustion. He drove himself in his work on the sculptures for his friend Sir Edward Maufe's new cathedral at Guildford, carving the figure of St John the Baptist in situ on the scaffold from October to December 1939.

Through summer 1940 Gill was seriously ill, first with German measles, then with congestion of the lung. He had been (and remained) an inveterate smoker, demonstrating working-class solidarity by rolling his own cigarettes. The onset of the Second World War depressed him beyond measure. In bed or in a deckchair in the garden, wrapped in a rug, he wrote his Autobiography (1940), an endearing, nostalgic ramble through his life that only hinted at facts he had earlier seemed on the brink of disclosing: 'I do not see how my kind of life, which is not that of a big game hunter, could be written without intimate details', he had told his publisher in 1933 (MS, Cape archive, University of Reading).

Lung cancer was diagnosed in October 1940. He refused the proposal of a pneumectomy and died in Harefield Hospital, Uxbridge, in the middle of a heavy air raid in the early morning of 17 November 1940. The funeral was held four days later at Pigotts, in the Gills' family chapel. Requiem mass was said according to the Roman rites. Gill's body was then transported in a farm cart for burial in the churchyard of the Baptist church at Speen, a curious reconnection with his dissenting ancestors. He had left characteristically exact instructions for his gravestone, allowing space for Mary. The inscription was cut by Laurie Cribb.

Gill's last major work of sculpture, the stone altarpiece for the English martyrs in St George's Chapel, Westminster Cathedral, was incomplete at his death, remaining at Pigotts through the war. In 1947, when it was eventually set in place, the small carved monkey, mischievously placed by Gill clinging to the bottom edge of the robes of Sir Thomas More, had been removed, presumably on the instructions of Westminster Cathedral authorities.

Reputation

Gill's declared intention was to 'have done something towards reintegrating bed and board, the small farm and the workshop, the home and school, earth and heaven' (Gill, Autobiography, 282). The energy and solemnity with which he pursued his ideals of integration were not negated by Gill's fallibilities and contradictions.

After the initial shock, especially within the Roman Catholic community, as Gill'shistory of adulteries, incest, and experimental connection with his dog became public knowledge in the late 1980s, the consequent reassessment of his life and art left his artistic reputation strengthened. Gill emerged as one of the twentieth century's strangest and most original controversialists, a sometimes infuriating, always arresting spokesman for man's continuing need of God in an increasingly materialistic civilization, and for intellectual vigour in an age of encroaching triviality.

Gill's reinvention of a 'holy tradition of workmanship', in the sense of a return to ideals of hand making and personal responsibility, helped to shape the individual workshop movement as it developed in Britain from the early 1970s, Gill's influence being particularly obvious on the flourishing craft of letter-cutting. His reputation as a sculptor was much strengthened by a series of exhibitions in the 1990s, in particular by his first large-scale retrospective, held at the Barbican Art Gallery in 1992. This finally defined Gill not simply as the twentieth century's leading British Roman Catholic artist, but as a key figure in early modernism, a superb advocate for the techniques of 'direct carving' later taken up by such sculptors as Frank Dobson, Barbara Hepworth, and Henry Moore.

Fiona MacCarthy DNB

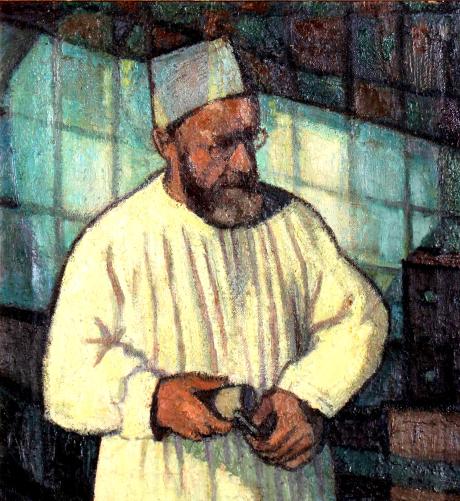

Geoffrey Robert Russell was a painter in oil and watercolour, specializing in landscapes, portraits and still life. He was born at Hayes in Kent on the 6th March 1902. he studied at St John's Wood Art School, then Westminster School of Art under Walter Bayes, Menninsky and Schwabe, and at Walter Sickert's School at Highbury 1927. He exhibited at the RA, RBA, ROI, RWA, NEAC, and at the Weymouth Arts Centre. He is represented in permenant collections of the R.W.A. he broadcasted regularly on art subjects, notably the series " Famous Artists and the West Country," 1956-1965. He signs his work "Robert Russell".