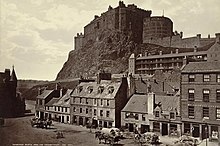

inscribed " Grass Market Heriots Hospital " and further inscribed in the margin " Edinburgh" a page from an album inscribed in the frontispage "F W Staines 3 Uplands St Leonards on Sea"

Amelia Jackson, Nee Staines (1842 – 1925) and thence by descent

The Grassmarket is a historic market place, street and event space in the Old Town of Edinburgh, Scotland. In relation to the rest of the city it lies in a hollow, well below surrounding ground levels.

The Grassmarket is located directly below Edinburgh Castle and forms part of one of the main east-west vehicle arteries through the city centre. It adjoins the Cowgatehead/Cowgate and Candlemaker Row at the east end, the West Bow (the lower end of Victoria Street) in the north-east corner, King's Stables Road to the north-west, and the West Port to the west. Leading off from the south-west corner is the Vennel, on the east side of which can still be seen some of the best surviving parts of the Flodden and Telfer town walls.

The view to the north, dominated by the castle, has long been a favourite subject of painters and photographers, making it one of the iconic views of the city.

First mentioned in the Registrum Magni Sigilii Regum Scotorum (1363) as "the street called Newbygging [new buildings] under the castle", the Grassmarket was, from 1477, one of Edinburgh's main market places, a part of which was given over to the sale of horses and cattle (the name apparently deriving from livestock grazing in pens beyond its western end),

Daniel Defoe, who was sent to Edinburgh as an English government agent in 1706, reported the place being used for two open air markets: the "Grass-market" and the "Horse-market". Of the West Bow at the north-east corner, considerably altered in the Victorian period, he wrote, "This street, which is called the Bow, is generally full of wholesale traders, and those very considerable dealers in iron, pitch, tar, oil, hemp, flax, linseed, painters' colours, dyers, drugs and woods, and such like heavy goods, and supplies country shopkeepers, as our wholesale dealers in England do. And here I may say, is a visible face of trade; most of them have also warehouses in Leith, where they lay up the heavier goods, and bring them hither, or sell them by patterns and samples, as they have occasion."

From 1800 onwards the area became a focal point for the influx of Irish immigrants and a high number of lodging houses appeared for those unable to pay a regular rent. Community views of these immigrants were polarised by the Burke and Hare murders on Tanners Close at West Port (the west end of the Grassmarket) in 1828. From the 1840s conditions were somewhat horrendous, with up to 12 people in what would now be deemed a small double bedroom, and occupants being locked in the room overnight. Police inspections had begun in 1822 but the rules themselves caused many of the problems. A further Act of 1848 combined police surveillance with limits on occupation. In 1888 the City Public Health Department recorded seven lodging houses holding a total of an incredible 414 persons. Crombies Land at the foot of West Port held 70 people in 27 bedrooms, with no toilet provision.

As a gathering point for market traders and cattle drovers, the Grassmarket was traditionally a place of taverns, hostelries and temporary lodgings, a fact still reflected in the use of some of the surrounding buildings. In the late 18th century the fly coach to London, via Dumfries and Carlisle, set out from an inn at the Cowgate Head at the eastern end of the market place. In 1803 William and Dorothy Wordsworth took rooms at the White Hart Inn, where the poet Robert Burns had stayed during his last visit to Edinburgh in 1791. In her account of the visit Dorothy described it as "not noisy, and tolerably cheap".In his 1961 film Greyfriars Bobby Walt Disney chose a lodging in the Grassmarket as the place where the Skye terrier's owner dies (depicting him as a shepherd hoping to be hired at the market rather than the real-life dog's owner, police night watchman John Gray).

The meat market closed in 1911 when a new municipal slaughter house at Tollcross replaced the old "shambles" in the western half of the Grassmarket (a road beyond the open market place) which joins King's Stables Road.

The association of the area with the poor and homeless only began to lessen in the 1980s: with Salvation Army hostels at both ends of the Grassmarket. Closure of the female hostel at the junction of West Port and the Grassmarket around 2000 in combination with an overall gentrification, capitalising on the street's location, began to truly change the atmosphere. Closure of the public toilets at the east end (a focal point for "jakeys" - drunken-down-and-outs) and comprehensive re-landscaping in the beginning of the 21st century has transformed the character of the area.

An inscribed flagstone in the central pavement in front of the White Hart Inn indicates the spot where a bomb exploded during a Zeppelin raid on the city on the night of 2–3 April 1916. Eleven people were killed in the raid, though none at this particular spot.

Archaeological excavations in the 2000s, by Headland Archaeology, on Candlemaker Row, in advance of new development, found that the archaeological evidence matches the historical records for the development of the Grassmarket. Candlemaker Row had activity from the 11th or 12th century onwards, possibly a farmstead, next to the confluence of two major cattle-droving routes into Edinburgh. The area was urbanized in the late 15th century, with the division of the land into burgage-plots and construction of a tenement, at the same time the market place was established in Grassmarket. In 1654, the magistrates designated the street for candle-making, thus how it got its name. The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw the redevelopment of the site and evidence for the use of the area as a brass foundry, in line with the Grassmarket being used as a slum at that time.

As a place of execution

The Grassmarket was also a traditional place of public executions.

A memorial near the site once occupied by the gibbet was created by public subscription in 1937. It commemorates over 100 Covenanters who died on the gallows between 1661 and 1688 during the period known as The Killing Time. Their names, where known, are recorded on a nearby plaque. One obdurate prisoner's refusal to escape death by swearing loyalty to the Crown prompted the snide remark by the Duke of Rothes that he had chosen to "glorify God in the Grassmarket".

In 1736, the Grassmarket formed the backdrop to the Porteous Riots which ended in the lynching of a captain of the Town Guard. A plaque near the traditional execution site now marks the spot where an enraged mob brought Captain Porteous's life to a brutal end.

A popular story in Edinburgh is that of Margaret (or Maggie) Dickson, a fishwife from Musselburgh, whose husband left, possibly press-ganged, to join the Royal Navy. Maggie had gone to work in an inn in the Borders, and was hanged in the Grassmarket in August 1724, at the age of 22 or 23, by hangman John Dalgliesh for murdering her illegitimate baby there by drowning it or placing it in the river Tweed at Kelso, shortly after the birth. After the hanging, a doctor declared Dickson dead, and her family argued with the medical students, who then were only allowed to dissect criminal corpses, so her body was taken back to Musselburgh on a cart. However, on the way there, the story was that her family went for a wake at an inn (possibly Sheep's Heid Inn, Duddingston) when they heard noises from the coffin as she awoke. Under Scots Law, her punishment had been carried out, so she could not be executed for a second time for the same crime (only later were the words "until dead" added to the sentence of hanging). Her "resurrection" was also to some extent seen as divine intervention, and so she was allowed to go free. In later life (and legend), she was referred to as "hauf-hingit Maggie" and attracted curiosity as she was seen back in the Grass-market in October 1724, with an item about a crowd forming to see her in the Scots Magazine. She remarried her husband (as ‘death’ had parted them) and lived another 40 years.

A poem in Scots appears in a book Quines by actress Gerda Stevenson.

"Hauf-hingit Maggie

Deith is wappin when it comes – like birth, I ken – I hae warstled throu, an focht wi baith. She wis blue, ma bairn, blue as the breast o a brid I seen oan the banks o the Tweed thon day; then grey, aa wrang, the naelstring windit ticht aroon her neck; I ettled tae lowse it, aince, twice, but it aye slippit – ma hauns couldnae grup, ma mind skailt frae the jizzen fecht, ma mooth steekit: no tae scraich, no tae scraich, let nane hear…

I stottered oot, doon tae the watter, thocht tae douk her in its cauld jaups, but ower late. I laid her quate in lang reeds, achin tae hae a bit basket tae float her oot like Moses, aa the wey tae England an the sea, gie her a deep grave, ayont kennin; but they fund her, still as a stane whaur she lay; an syne me, wannert gyte agate Kelso toun. “Murther!” they yaldered, “Murther!” like dugs.

Embro Tolbooth’s a dowie jyle. An mercy? Nane they gied me at ma trial—the verdict: hingin. The duimster slippit the towe ower ma heid, drapt the flair – but I’d lowsed ma hauns, I gruppit thon raip, aince, twice, thrice at ma thrapple – I’d dae it this time! The duimster dunted me wi his stick, dunt, dunt, an the dirdum dinged in ma lugs, “Clure the hure! Clure the huir!” Syne aa gaed daurk.

A chink o licht. The smell o wuid, warm – a cuddie’s pech; ma een appen. I lift ma nieve, chap, chap oan ma mort-kist lid, chap, chap! A scraich ootbye, a craik o hinges. I heeze masel, slaw, intil ma ain wake, at the Sheep Heid Inn. Fowk heuch an flee: “A ghaist, a bogle, risin fae the deid!” I sclim oot, caum. The braw Brewster gies me a wink, hauns me a dram. I sup lang the gowd maut, syne dauner back tae life, an hame."

There is now a pub in the Grassmarket named Maggie Dickson's near where she was hanged.

In 1775, the young advocate James Boswell's first criminal client, John Reid from Peeblesshire, was hanged in the Grassmarket for sheep-stealing. Boswell, convinced of his client's innocence and citing Maggie Dickson's miraculous recovery, hatched a plan to recover Reid's corpse immediately after execution and have it resuscitated by surgeons. He was finally dissuaded from this course of action by a friend who warned him that the condemned man had become resigned to his fate and might well curse Boswell for bringing him back to life.

Sir Walter Scott described his memory of the Grassmarket gibbet in his novel The Heart of Midlothian published in 1818.

The fatal day was announced to the public, by the appearance of a huge black gallows-tree towards the eastern end of the Grassmarket. This ill-omened apparition was of great height, with a scaffold surrounding it, and a double ladder placed against it, for the ascent of the unhappy criminal and the executioner. As this apparatus was always arranged before dawn, it seemed as if the gallows had grown out of the earth in the course of one night, like the production of some foul demon; and I well remember the fright with which the schoolboys, when I was one of their number, used to regard these ominous signs of deadly preparation. On the night after the execution the gallows again disappeared, and was conveyed in silence and darkness to the place where it was usually deposited, which was one of the vaults under the Parliament House, or courts of justice."

The old market area is surrounded by pubs, restaurants, clubs, local retail shops, and two large Apex Hotels.

North-east corner of the Grassmarket. Until 1764 public hangings took place on a spot just to the left of the yellow traffic sign. Thereafter, they were carried out at the Old Tolbooth in the High Street and then at the Lawnmarket.

The building dates range from 17th century to 21st century. The White Hart Inn dates from the early 18th Century and claims to be the oldest public house in Edinburgh and is said to have been visited by Robert Burns (1759–96), the Wordsworths (1803), William Burke and William Hare in the late 1820s.

The City Improvement Scheme of 1868 cleared many of the slums and widened streets such as West Port, and the western group of buildings all derive from this plan. A further improvement plan in the 1920s by the City architect Ebenezer MacRae skilfully closed many of the gaps with faux Scots Baronial blocks, ironically all built as council housing.

There are several modern buildings on its southern side. Some properties were used by Heriot-Watt University, and its predecessor college, for teaching and research until the university moved fully to its new Riccarton campus (1974–92).The Mountbatten Building of Heriot-Watt University was built in 1968) for the departments of electrical engineering, management and languages. The Mountbatten building was converted and reopened as the Apex International Hotel in 1996.

An example of 21st century architecture is Dance Base (2001) by Malcolm Fraser Architects, the Scottish National Centre for Dance, which runs back from a traditional frontage to a multi-level design on the slopes of the Castle Rock; the design won a Civic Trust Award and Scottish Design Award in 2002.

For most of its history the Grassmarket was one of the poorest areas of the city, associated in the nineteenth century with an influx of poor Irish and the infamous murderers Burke and Hare. Up until quite recently it was still to some extent associated with homelessness and drunkenness before its rapid gentrification as a popular tourist spot. The character of the area was reflected in a number of hostels for the homeless, including that of the Salvation Army Women's Hostel (now a backpackers hostel) which existed here until the 1980s. From then on property prices started to rise sharply.

The area is, and always has been, dominated by a series of public houses. In recent years many have become more family-friendly and include dining areas. The council has recently further encouraged these to spill over onto outside pavements, giving the place a more Continental atmosphere.

The Grassmarket was subject to a streetscape improvement scheme carried out 2009–10 at a cost of £5 million. Measures aimed at making the area more pedestrian-friendly included the extension of pavement café areas and the creation of an "events zone".

The "shadow" of a gibbet was added in dark paving on the former gallows site (next to the Covenanters' Monument) and the line of the Flodden Wall at the western end delineated by a strip of lighter paving from the Vennel on the south side to the newly created Granny's Green Steps on the north side.

George Heriot's School is a private primary and secondary day school on Lauriston Place in the Lauriston area of Edinburgh, Scotland. In the early 21st century, it has more than 1600 pupils, 155 teaching staff, and 80 non-teaching staff. It was established in 1628 as George Heriot's Hospital, by bequest of the royal goldsmith George Heriot, and opened in 1659. It is governed by George Heriot's Trust, a Scottish charity.

The main building of the school is notable for its renaissance architecture, the work of William Wallace, until his death in 1631.He was succeeded as master mason by William Aytoun, who was succeeded in turn by John Mylne. In 1676, Sir William Bruce drew up plans for the completion of Heriot's Hospital. His design, for the central tower of the north façade, was eventually executed in 1693.

The school is a turreted building surrounding a large quadrangle, and built out of sandstone The foundation stone is inscribed with the date 1628. The intricate decoration above each window is unique (with one paired exception - those on the ground floor either side of the now redundant central turret on the west side of the building). A statue of the founder can be found in a niche on the north side of the quadrangle.

The main building was the first large building to be constructed outside the Edinburgh city walls. It is located next to Greyfriars Kirk, built in 1620, in open grounds overlooked by Edinburgh Castle directly to the north. Parts of the seventeenth-century city wall (the Telfer Wall) serve as the walls of the school grounds. When built, the building's front facade faced north with access from the Grassmarket by way of Heriot Bridge. It was originally the only facade fronted in fine ashlar stone, the others being harled rubble. "George Heriot's magnificent pile" became known locally, and by the boys who attended it, as the "Wark".

In 1833 the three rubble facades were refaced in Craigleith ashlar stone. This was done because the other facades had become more visible when a new entrance was installed on Lauriston Place. The refacing work was handled by Alexander Black, then Superintendent of Works for the school. He later designed the first Heriot's free schools around the city.

The south gatehouse onto Lauriston Place is by William Henry Playfair and dates from 1829. The chapel interior (1837) is by James Gillespie Graham, who is likely to have been assisted by Augustus Pugin. The school hall was designed by Donald Gow in 1893 and boasts a hammerbeam roof. A mezzanine floor was added later. The science block is by John Chesser (architect) and dates from 1887, incorporating part of the former primary school of 1838 by Alexander Black (architect). The chemistry block to the west of the site was designed by John Anderson in 1911.

The grounds contain a selection of other buildings of varying age; these include a wing by inter-war school specialists Reid & Forbes, and a swimming pool, now unused. A 1922 granite war memorial, by James Dunn, is dedicated to the school's former pupils and teachers who died in World War I. Alumni and teachers who died in World War II were also added to the memorial.

On his death in 1624, George Heriot left just over 23,625 pounds sterling – equivalent to about £3 million in 2017 – to found a "hospital" (a charitable school) on the model of Christ's Hospital in London, to care for the "puir, faitherless bairns" (Scots: poor, fatherless children) and children of "decayit" (fallen on hard times) burgesses and freemen of Edinburgh.

The construction of Heriot's Hospital (as it was first called) was begun in 1628, just outside the city walls of Edinburgh. It was completed in time to be occupied by Oliver Cromwell's English forces during the invasion of Scotland during the Third English Civil War. When the building was used as a barracks, Cromwell's forces stabled their horses in the chapel. The hospital opened in 1659, with thirty sickly children in residence. As its finances grew, it took in other pupils in addition to the orphans for whom it was intended.

By the end of the 18th century, the Governors of the George Heriot's Trust had purchased the Barony of Broughton, thus acquiring extensive land for feuing (a form of leasehold) on the northern slope below James Craig's Georgian New Town. This and other land purchases beyond the original city boundary generated considerable revenue through leases for the Trust long after Heriot's death.

In 1846 there was an insurrection in the Hospital and fifty-two boys were dismissed. This was the worst of several disturbances in the 1840s. Critics of hospital education blamed what they described as the monastic separation of the boys from home life. Only a minority (52 out of 180 in 1844) were fatherless, which meant, these critics argued, that poorer families were leaving their children to Hospital care, even through holiday periods, and the influence of disaffected older boys. 'Auld Callants' (former pupils) were prepared to defend the Hospital as a source of hope and discipline to families in difficulties. This argument about the value of hospitals, which reached the pages of The Times in late 1846, was taken up by Duncan McLaren when he became Lord Provost of Edinburgh, and therefore Chairman of the Hospital Governors, in 1851. McLaren pushed for the number of boys in the Hospital to be reduced and for the Heriot outdoor schools to be expanded with the resources thus saved.

Duncan McLaren was the primary initiator of the 1836 Act that gave the Heriot Governors the power to use the Heriot Trust's surplus to set up "outdoor" (i.e. outside the Hospital) schools. Between 1838 and 1885 the Trust set up and ran 13 juvenile and 8 infant outdoor schools across Edinburgh. At its height in the early 1880s this network of Heriot schools, which did not charge any fees, had a total roll of almost 5,000 pupils. The outdoor Heriot school buildings were sold off or rented out (some to the Edinburgh School Board) when the network was wound up after 1885 as part of reforms to the Trust and the absorption of its outdoor activities by the public school system.Several of these buildings, including the Cowgate, Davie Street, Holyrood and Stockbridge Schools, were designed with architectural features copied from the Lauriston Place Hospital building or stonework elements referring to George Heriot.

George Heriot’s Hospital was at the centre of the controversies surrounding Scottish educational endowments between the late 1860s and the mid 1880s. At a time when general funding for secondary education was not politically possible, reform of these endowments was seen as a way to facilitate access beyond elementary education. The question was, for whom; those who could afford to pay fees or those who could not? The Heriot’s controversy was therefore a central issue in Edinburgh municipal politics at this time. In 1875 a Heriot Trust Defence Committee (HTDC) was formed in opposition to the recommendations of the (Colebrooke) Commission on Endowed Schools and Hospitals, set up in 1872. These included making the Hospital a secondary technical day school, using Heriot money to fund university scholarships, introducing fees for the outdoor schools and accepting foundationers from outside Edinburgh. The HTDC saw this as a spoliation of Edinburgh’s poor to the benefit of the middle classes. Already in 1870, under the permissive Endowed Institutions (Scotland) Act of the previous year, and again in 1879 to the (Moncreiff) Commission on Endowed Institutions in Scotland, and finally in 1883 to the (Balfour) Commission on Educational Endowments, Heriot’s submitted schemes of reform. All were turned down. The reasons included Heriot’s continuing commitment to free and hospital education, and its maintenance of the Heriot outdoor schools after the passage of the Education (Scotland) Act in 1872 brought in publicly supported, compulsory elementary education. The Balfour Commission had executive powers and used these in 1885 to impose reform on Heriot’s. The Hospital became a day school, charging a modest fee, for boys of 10 and above. Up to 120 foundationers, no younger than 7 years of age, enjoyed preferential admission. Greek was not to be taught. The new George Heriot's Hospital School was, in other words, to be a modern, technically oriented institution. The outdoor school network was to be wound up and the resources used for a variety of scholarships and bursaries, including a number to be used for attendance at the High School and University of Edinburgh. These, rather than the new Heriot's day school, were to provide a path to university education for those able and interested. There were elements in this scheme of a response to contemporary European educational reforms, such as that exemplified by the German Realschulen.

The most uncontroversial aspect of the Balfour Commission’s scheme of 1885 for the reform of the Heriot's Hospital and Trust was the takeover of the "Watt Institution and School of Arts" by the Trust. This was to be renamed the Heriot-Watt College. This was not just a matter of the Trust providing financial support, but was part of a policy of encouraging technical education in Edinburgh. Provision was especially to be made for pupils to continue their studies after completing the higher classes of the new Heriot’s day school. The School and the College were both run under the Heriot board of governors until the development and financial needs of the College required a separation in 1927. The Trust continued to make a contribution to the College of £8,000 p.a. thereafter.In 1966 the College was granted university status as Heriot-Watt University.

In 1979 Heriot's became co-educational after admitting girls. In the same year Lothian Regional Council attempted to bring the school in to the local authority system, but the Secretary of State for Scotland intervened.

In the early 21st century, George Heriot's has approximately 1600 pupils. It continues to serve its charitable goal by providing free education to children who are bereaved of a parent, such children being referred to as "foundationers". In 2012, the school was ranked as Edinburgh's best performing school by Higher exam results.

Chronological list of the headmasters of the school, the year given being the one in which they took office.[30]

- 1659 James Lawson

- 1664 David Davidsone

- 1669 David Browne

- 1670 William Smeaton

- 1673 Harry Moresone

- 1699 James Buchan

- 1702 John Watson

- 1720 David Chrystie

- 1734 William Matheson

- 1735 John Hunter

- 1741 William Halieburton

- 1741 John Henderson

- 1757 James Colvill

- 1769 George Watson

- 1773 William Hay

- 1782 Thomas Thomson

- 1792 David Cruikshank

- 1794 James Maxwell Cockburn

- 1795 George Irvine

- 1805 John Somerville

- 1816 John Christison

- 1825 James Boyd

- 1829 Hector Holme

- 1839 William Steven

- 1844 James Fairburn

- 1854 Frederick W. Bedford

- 1880 David Fowler Lowe

- 1908 John Brown Clark

- 1926 William Gentle

- 1942 William Carnon

- 1947 William Dewar

- 1970 Allan McDonald

- 1983 Keith Pearson

- 1997 Alistair Hector

Thereafter, the title of Headmaster was changed to that of Principal.

- 2014 (January) Gareth Doodes

- 2014 (September) Cameron Wyllie (Acting)

- 2014 (December) Cameron Wyllie

- 2018 (January) Mrs Lesley Franklin

- 2021 (August) Gareth Warren

- James Craik, Classics, c.1822 to c.1832

- John Watt Butters, Maths, 1888 to 1899

- James Stagg, Science, 1921 to 1923

- Donald Hastie, Games, 1949 to 1979[34] Hastie was reportedly the first full-time games master in Scotland.

- Ray Milne, French and German, 1974 to 1978

- Sam Mort, English and Drama (1997 to 2001), in 2021 Unicef chief of Communication, Advocacy and Civic Engagement in Afghanistan

Former pupils' clubs, the Heriot's Rugby Club and Heriot's Cricket Club, carry the School's name and use the School's Goldenacre grounds. George Heriot's School Rowing Club competes at a national level and is affiliated to Scottish Rowing. There is a pipe band, and around 120 pupils take tuition of some kind.

Academia and Science

- George Alexander Carse (1880 – 1950) - physicist (dux in 1898)

- J. W. S. Cassels, FRS (1922 – 2015) - mathematician

- Henry Daniels, FRS (1912 – 2000) - statistician

- Robin Ferrier (1932 – 2013) - organic chemist

- Sir George Taylor (botanist) (1904 - 1993)

- Sir Thomas Dalling (1892 - 1982) - Professor of Animal Pathology at Cambridge and Chief Veterinary Officer to the United Kingdom

- John Borthwick Gilchrist (1759 – 1841) - Indologist

- Professor Sir Abraham Goldberg (1923 – 2007), KB MD DSc FRCP FRSE - Emeritus Regius Professor of Medicine, University of Glasgow

- Professor Hyman Levy (1889 – 1975), FRSE - Scottish philosopher, mathematician, political activist

- Sir Harry (Work) Melville (1908 – 2000), FRSE - polymer chemist and administrator

- Professor Hamish Scott FBA FRSE (b. 1946) - historian

- Professor Gordon Turnbull (b. ) - psychiatrist

- Professor Douglas C. Heggie (b. 1947), FRSE - Personal Chair of Mathematical Astronomy, School of Mathematics, University of Edinburgh

- Alexander Burns Wallace (1906–1974) - plastic surgeon

Media and Arts

- Nick Abbot (b. 1960) - radio broadcaster

- Ian Bairnson (b. 1953) - musician, member of Pilot and The Alan Parsons Project

- Emun Elliott (b. 1983) - actor

- Gavin Esler (b. 1953) - television journalist and presenter of Newsnight

- Mark Goodier (b. 1961) - Radio One disc jockey

- Mike Heron (b. 1942) - musician, formerly of the Incredible String Band

- Roy Kinnear (1934 – 1988) - actor

- Duncan Hendry (1951 - 2003) - Chief Executive of Aberdeen Performing Arts and of Edinburgh's Capital Theatres

- Iain Macwhirter (b. 1953) - journalist and Rector of the University of Edinburgh (2009 – 2012)

- Henry Raeburn (1756 – 1823) - painter

- Ian Richardson (1934 – 2007) - actor

- Mike Scott (musician) (b. 1958) - musician and composer, founder of The Waterboys

- Alastair Sim (1900 – 1976) - actor

- Ken Stott (b. 1955) - actor

- Bryan Swanson (b. 1980) - Sky Sports chief reporter

- Nigel Tranter (1909 – 2000) - historical novelist

- Robert Urquhart (1921 – 1995) - actor

- Charlotte Wells - film director

- Paul Young (actor) (b. 1944) - actor

Law and Politics

- Tasmina Ahmed-Sheikh (b. 1970) - SNP politician

- James Mackay, Baron Mackay of Clashfern (b. 1927) - Advocate and former Lord Chancellor

- David McLetchie (1952 – 2013) - former leader of the Scottish Conservatives

- Doug Naysmith (b. 1941) - Labour politician and former MP for Bristol North West

- Keith Stewart, Baron Stewart of Dirleton - HM Advocate General for Scotland

- Gordon Prentice (b. 1951) - Labour politician and former MP for Pendle

- Stephen Woolman, Lord Woolman (b. 1953) - Senator of the College of Justice

- Kenneth Borthwick CBE DL JP (1915 – 2017) - Lord Provost of Edinburgh (1977 to 1980), Chairman of the 1986 Commonwealth Games

- Sir Adam Wilson (1814 – 1891) - 15th mayor of Toronto, member of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada

Sports

- Bruce Douglas (b. 1980) - Rugby Union player

- Charles Groves (1896–1969) - cricketer

- Andy Irvine (b. 1951) - Rugby Union internationalist

- Iain Milne (b. 1956) - Rugby Union player

- Kenny Milne (b. 1961) - Rugby Union player

- Robert More (b. 1980) - cricketer

- John Mushet (1875–1965) - cricketer

- Gordon Ross (b. 1978) - Rugby Union player

- Ken Scotland (b. 1936) - Rugby Union internationalist

- Polly Swann (b. 1988) - Member of the GB Rowing Team, and Rowing World Champion

- Douglas Walker (b. 1973) - sprinter

Military

- Colonel Clive Fairweather (1944 – 2012) - 2nd in command of the SAS during the Iranian Embassy siege.[49]

- David Stuart McGregor (1895 – 1918) - Scottish recipient of the Victoria Cross

Religion

- Graham Forbes, CBE (b. 1951) - Provost of St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh

- Hector Bransby Gooderham (1901 – 1977) - priest of the Scottish Episcopal Church

- Gordon Keddie (b. 1944) - Reformed Presbyterian minister and theologian

- James Pitt-Watson (1893–1962) - theologian and Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

- Brian Smith (bishop) (b. 1943) - Bishop of Edinburgh (Scottish Episcopal Church) 2001–2011

Other

- James Aitken, aka "John the Painter" (1752 – 1777) - mercenary

- Hippolyte Blanc (1844 – 1917) - architect

- Archie Forbes (1913 – 1999), CBE - Colonial administrator

- Norman Irons (b. ) - former Lord Provost of Edinburgh

- Sir Andrew Hunter Arbuthnot Murray (1903 – 1977) - former Lord Provost of Edinburgh

- Stuart Harris (1920 – 1997), architect and local historian

Francis William Staines was the last of a family of merchants from the City of London. Not only was he a successful businessman but he possessed a large independent fortune, such that he could devote his time to the cultivation of his talents in music and art. He was a brilliant amateur violinist, and also loved to spend much of his time painting. His daughter Amelia and her mother accompanied Mr Staines as he travelled throughout the country finding subjects for his painting. One area of the country that they visited frequently was Scotland and the Lake District, and Amelia grew particularly fond of the dramatic landscape of the Fells. Skelwith Bridge with the view of the hills around it 43 was one of her father’s favourite scenes. He painted landscapes and maritime paintings , exhibited 11 works at the RA including views on the Italian Coast, address in London, Hastings and St Leonards on Sea Susssex.